Featured photographer

Tim Parkin

Amateur Photographer who plays with big cameras and film when in between digital photographs.

David Taylor

David Taylor is a professional freelance landscape photographer and writer who lives in Northumberland. His first camera was a Kodak Instamatic. Since then, he’s used every type of camera imaginable, from bulky 4x5 film cameras to pocket-sized digital compacts. David has written over 40 books, as well as supplying images and articles to both regional and national magazines and newspapers. He also runs one-to-one workshops in north-east England. When David is not outdoors, he can be found at home with his wife, a cat, and an increasingly large number of tripods.

Our featured photographer this issue hails from Northumberland and has developed his landscape photography into a career after leaving the videogame industry in 2004.

In most photographers lives there are 'epiphanic’ moments where things become clear, or new directions are formed. What were your two main moments and how did they change your photography?

Oddly enough my first ‘epiphany’ came long before I owned a camera. It was on a ferry trip from the Kyle of Lochalsh to Mallaig when I was a teenager. The weather didn’t look promising when we set off, there was low cloud and the sea was choppy and grey. However, I was transfixed on the journey south by the quality of the light. There was a ‘silveriness’ to the landscape that I thought was just magical. It’s surprising that I didn’t immediately take up black and white photography right there and then. It’s taken about twenty-five years but I’m finally coming round to the idea.

Oddly enough my first ‘epiphany’ came long before I owned a camera. It was on a ferry trip from the Kyle of Lochalsh to Mallaig when I was a teenager. The weather didn’t look promising when we set off, there was low cloud and the sea was choppy and grey. However, I was transfixed on the journey south by the quality of the light. There was a ‘silveriness’ to the landscape that I thought was just magical. It’s surprising that I didn’t immediately take up black and white photography right there and then. It’s taken about twenty-five years but I’m finally coming round to the idea.

The second epiphany came on a family trip to the Lake District. I had my first camera at this point - a Cosina CT-1 if I remember rightly. After I had the film developed there was one shot that I thought had some merit. Enough merit to encourage me to keep trying so that every shot I took had merit. I’m still trying!

You nearly studied art in further education but this didn’t pan out. Tell us a little bit about what attracted you to art and what happened to stop you going to college/uni?

As long as I can remember I’ve been interested in drawing and painting. My dream job when I was a teenager was to be a cartoonist. There’s something thrilling about making marks on a piece of paper and creating something recognizable. That thrill has transferred to photography now, but it’s still there and is central to who I am.

I stopped formal education after A-Levels. I had intended on continuing on to university but got distracted by a career in computer game development. This distraction lasted about twenty years, starting with the creating graphics for the Sinclair Spectrum and ending with PlayStation 2. At some point, I really need to write down all that happened during that period… During that time photography bubbled under as a hobby, ironically because it was very much non-computer related and so different to the day job.

I stopped formal education after A-Levels. I had intended on continuing on to university but got distracted by a career in computer game development. This distraction lasted about twenty years, starting with the creating graphics for the Sinclair Spectrum and ending with PlayStation 2. At some point, I really need to write down all that happened during that period… During that time photography bubbled under as a hobby, ironically because it was very much non-computer related and so different to the day job.

You now make your money through landscape photography, when did this start and did it meet expectations?

My first paying photographic job was for the Northumberland National Park. That was in 2003/4. However, I didn’t become a full-time photographer until 2006. With impeccable timing that was just before the biggest financial crisis for a generation!

The business of making a living as a photographer is different to how I imagined it. Not better or worse, just different. It’s a far more varied existence than I expected. And I’ve met some inspiring and wonderful people along the way, which has been a very pleasant bonus.

The business of making a living as a photographer is different to how I imagined it. Not better or worse, just different. It’s a far more varied existence than I expected. And I’ve met some inspiring and wonderful people along the way, which has been a very pleasant bonus.

Any painful learning you are willing to share?

For some reason, I thought it would be possible to make a living just selling stock! When I first joined Alamy there were about four million images available on their website. There are now more than twenty million (with fifteen thousand added every day apparently). Unless you have the mind of a crossword addict and are privy to the secrets of how Alamy works it’s getting harder and harder to be found by picture buyers. That said my sales have increased over time, just not to the point where I can put my feet up and think that I’ve finally made it.

Could you tell us a little about the cameras and lenses you typically take on a trip and how they affect your photography.

There’s a very fine balance between the number of lenses you can carry and the number of sandwiches. I now tend to err on the side of sandwiches and so keep my lens selection simple. I shoot with a Canon 7D and a 17-40mm lens. If I’m cutting back on the sandwiches I’ll also take a 50mm and 70-200mm lens.

The 7D is a crop sensor camera, something I’m not quite used to yet! The 17-40mm lens often doesn’t seem ‘wide’ enough. At some point, I may have to invest in either a wider lens or a full-frame camera. For the moment though I do seem to be shying away from the ‘bigger’ landscape in favour of the more intimate. Whether that will change if I get my hands on a ‘wider’ lens is an interesting thought.

The 50mm lens I think is wonderful. On the 7D it’s ‘longer’ than if it were on a full-frame camera. However, I can live with that because it’s an optically excellent lens and it’s fast. I've become more and more interested in using wide-apertures. For me, the idea that everything in an image has to be sharp is being slowly eroded – though old habits die hard! This change partly comes from a fascination with photos from the 19th and early 20th century – particularly those shot with ‘cheap’ cameras such as Box Brownies. They have such a distinctive and evocative visual quality.

I have seen your work on St Cuthbert's way. Could you tell us a little about this and are you working on any current projects?

I have seen your work on St Cuthbert's way. Could you tell us a little about this and are you working on any current projects?

The Cheviot Hills in Northumberland I find particularly inspiring. On visits to the hills around Wooler I started noticing signs for the St. Cuthbert’s Way. That sparked an interest in documenting the route photographically.

For those who don’t know, the St. Cuthbert’s Way is a 62-mile long-distance path across the country that would have been familiar to the saint. It starts near St. Cuthbert’s birthplace in the town of Melrose in the Scottish Borders, cuts east into Northumberland, ending on Holy Island where he died. The landscape along the route is a mix of moorland, farmland and coast. It’s very inspiring – and photographically – far easier to document than the Pennine Way! I spent a year visiting and re-visiting locations along the route to try and capture it across the seasons. After the project was complete it was turned into a touring exhibition at venues as close to the route as I could find.

My current project involves a return to the Cheviots to document the various valleys in the range. There are four main valleys in the Northumberland Cheviots and each has a different look and character. Hopefully, all this work will be turned into a book in the next year or so.

Tell me what your favourite two or three photographs are and a little bit about them.

My favourite photographs invariably change over time. However, the ones that are still special to me are those that, at the time, involved special effort or the overcoming of an obstacle.

This shot from the beach near Bamburgh wasn’t the one I’d pre-visualised. I was in the process of setting up when another photographer walked down from the nearby car park, right across the pristine sand of my intended composition. I followed his progress across the beach, giving him my best Paddington Bear stare, until I realised that I had a new, and better, shot to create! Since then I’ve been a bit more open to the idea of the happy accident in the creation of a photograph…

Getting wet seems to be in the job description of the landscape photographer. I’d spent a fruitless afternoon up on the slopes of Henhole in the College Valley, getting more and more wet from the rain that didn’t seem to want to stop falling. I had finally given up and was on my way back down to the car when the clouds finally parted and a theatrical light illuminated the valley below. Oddly enough I didn’t mind the fact that I was soaked through after I’d exposed this image.

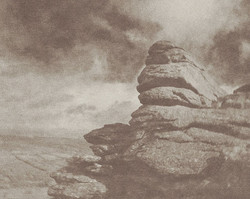

Keeping a tripod steady when the wind is howling in across open moors is always an interesting challenge. Cawfields Crag in Northumberland is a favourite spot of mine. It’s the northeast’s Half Dome! Though admittedly a fraction of the size…I was inspired to make this image because strong winds were whipping the trees around quite violently, but of course Cawfields was as steady as a…er rock. I was taken with this contrast and wanted to capture the essence of it, even if it meant leaning against the tripod to keep it from toppling over.

What sort of post processing do you undertake on your pictures? Give me an idea of your workflow.

What sort of post processing do you undertake on your pictures? Give me an idea of your workflow.

I work purely digitally now so the first task after a day’s shooting is importing the files. I use Lightroom for importing, converting the camera’s RAW files to DNG. Once the files have been imported I back them up to DVD and begin to whittle the selection down to those images that I want to keep. I then use Lightroom to make any necessary tonal adjustments such as contrast or white balance as well as adding keywords and descriptions. I do try to expose an image correctly in-camera, using ND Graduate filters if necessary. If I’ve done my job right I don’t have to spend too long in Lightroom adjusting images, but invariably there are adjustments to be made. Once I’m happy with an image it’s exported as a 16-bit TIFF for a final spit and polish in Photoshop.

What are your thoughts on exhibitions? Are they profitable or is the benefit non-financial?

What are your thoughts on exhibitions? Are they profitable or is the benefit non-financial?

Putting on an exhibition is an enjoyable process and one that even occasionally pays for itself! Beyond the purely financial there are intangible benefits to hosting an exhibition. The most obvious one is that an exhibition is great opportunity to meet people and receive feedback on your photography. A less obvious benefit is that creating an exhibition forces you to think about whether a series of images works as a collection and if they do, how they should be ordered within the exhibition space.

Do you print much of your work? If so how have you approached it and if not, why not?

I don’t print my own work, that’s done for me by Peak Imaging in Yorkshire and Digitalab in Newcastle. I like the idea of printing my own images but I’m very happy with the quality of the Fuji Crystal Archive paper that Peak and Digitalab use. That said I am becoming more interested in black and white photography and the range of textured paper that is available for inkjet printing is a tempting prospect to explore further.

Tell us a little bit about the workshops you run and what your ‘unique selling point’ is.

My workshops are one-day small-group affairs, mainly based in my home county of Northumberland. My unique selling point? I work on the basis that people are there to enjoy their day – and learn something in the process. For me the two are interlinked. So, I try to make sure that participants are put at their ease and to start the day by discussing what they’d like to achieve during the workshop. From then on, the day is tailored (or is it taylored?) to those initial responses. Because I prefer to stick to small groups (no more than six) that gives me an opportunity to see everybody in the group individually during the day.

Tell me about the photographers that inspire you most.

Tell me about the photographers that inspire you most.

In terms of landscape photography - if it’s not too embarrassing! - I’d have to say Joe Cornish. I’ve been lucky enough to attend several of Joe’s workshops and come away suitably inspired with concepts and ideas to mull over and put into practice.

For non-landscape photography, I’d have to nominate Elliott Erwitt. If I were only allowed to keep one photography book it would have to be Erwitt’s ‘Snaps’. It’s an astonishing body of work that I keep returning to.

If you were told you couldn’t do anything art/photography related for a week, what would you end up doing (i.e. Do you have a hobby other than photography..)

I never seem to be able to find the time to curl up and have a really good read. That’s what I’d do with my week! I’m very interested in history, particularly British 20th century history. I’d spend my week working my way back through Dominic Sandbrook’s three books that cover the 1960s and 70s. If that could be done with some good music playing in the background I’d be more than happy.

What sorts of things do you think might challenge you in the future or do you have any photographs or styles that you want to investigate?

What sorts of things do you think might challenge you in the future or do you have any photographs or styles that you want to investigate?

I’m becoming more and more interested in black and white photography (a photographer friend told me that I was finally taking up proper photography…). Black and white photography is a huge subject; one that I don’t think could be exhausted in one lifetime. At least not a life that involved sleep and other inconvenient activities! I like the idea of embarking on something that has no real end, where there is always something new to learn. It would be terrible to feel as though you knew everything there was to know about a subject.

Where do you see your photography going in terms of subject and style?

This is probably heresy, but I’d like to learn more about architectural photography! It’s as challenging as landscape and, even just within Britain, would be a subject that could never be exhausted.

Who do you think we should feature as our next photographer?

Mike McFarlane and Stewart Smith are both producing interesting work in northern England.

---

Thanks to David for some great answers and stories. You can see more of David's work at http://www.davidtaylorphotography.co.uk/