Do musicians make good photographers?

I found Tim’s article (in Issue 15) on the link between the practice of photography and learning to play music thought-provoking in lots of ways, but one point it didn’t address was the similarities in the evolution of our artistic preferences as we learn the different arts. This is going to be emotive and probably controversial, so get ready.

Having learned to play the piano as an adult, and also become interested/obsessed with landscape photography in my thirties, I’ve been amazed at the similar trajectories. Indulge me: I decided to learn piano because I was bowled over by the beauty of some (relatively) simple pieces: some of Bach’s preludes and so on. I couldn’t understand why pianist friends were obsessed with the “widdly widdly widdly” exercises of Liszt et al, nor could I see any merit – in fact I could only see pretentious perversion – in the off-beat rhythms of Bartok or the exotic harmonies and disharmonies of Scriabin, Medtner and so on. And trust me you can go way further off the beaten track than that, and I did.

Inevitably, as the kinetic pleasure of playing became more an end in itself, the “technique-lust” did take over for a while: hours of études, total obsession. But then, having made some progress (sadly that is not false modesty), I realised that my tastes had changed behind my back just as my technique had improved; the flamboyant pyrotechnic pieces had lost their allure as soon as they were mastered (hacked through, if I’m honest), and I found myself drawn back to the pieces I had originally loved, but heard them afresh and realised just how good they were in ways I hadn’t originally recognised, and craved to the more complex rhythms, tones and harmonies of exactly the composers I had originally dismissed. The Greats were still unapproachably great, I knew, but there was a different kind of satisfaction when tension was built up and released in more complex ways; although I had been passionate about music for years before learning an instrument, it was only after regular effort at learning to play that I really learned not only to hear but also to refine my understanding of what I liked to listen to and why. The music I grew to love was not better than the pieces that drew me in, just great in different ways.

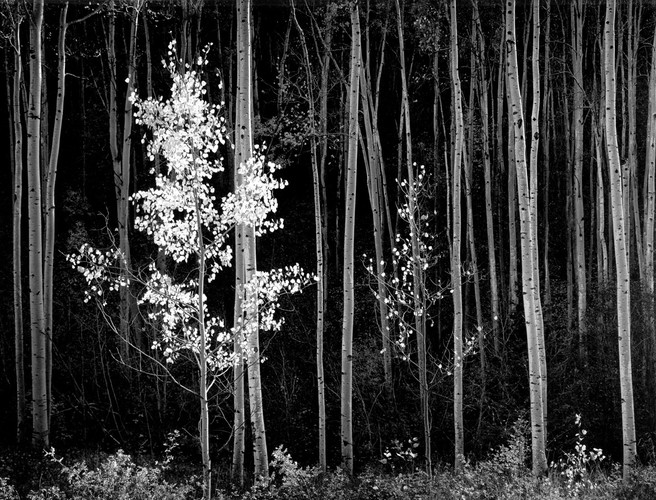

Side-track over; why do I tell you this? Because the same thing happened when I became hooked on landscape photography, and talking to many others (and, through the miracle of Flickr, actually watching their photographic voices evolve) it seems that an awful lot of people share the same trajectory. At first, probably for pretty much everyone, the love of “you know, just beautiful” images: Ansel Adams on an Athena poster, National Trust images (I don’t mean that in any way condescendingly but rather to emphasize their broad appeal), photos of beautiful coastal dawns, and so on, all leading to an initial desire to practice and to become better oneself.

The next stage in this archetypal progress, God help us, is often an obsession with the kit, dramatic light, technique, and (frankly) overdoing processing in the Spinal Tap manner:“Hey wow! This saturation goes to 11: and just look how much contrast and sharpening I can put in!”. If you’re into film, an almost religious addiction to nothing but Velvia. (For some people, HDR: but for them, it is a long, long road back…) Perhaps an obsession with “golden hour light”, and intense colour, even where there is effectively no composition or personal stamp on an image apart from being the only person mad enough to get up sufficiently early and insufficiently awful weather to make the photo, and often photos of the usual suspects; I have definitely indulged.

Durdle Door. Light, colour and “actually being there” in spades; but not much opportunity for composition or anything else.

Then eventually, for many, a refinement of these various influences and factors overlaid with a growing awareness of one’s own particular “voice”, to produce great, classical-style landscape photography, unarguably good; still the light and the colour and the boldness, but a greater and more effortless mastery of composition, arrangement and tonality to produce a more satisfactory total work of art. More of the same, in other words, just much much better. For others, a movement to complexity or to simplicity, perhaps an obsession with arrangement and understatement; and perhaps painted with a tonally softer palette. Perhaps a more graphic or abstract impulse; there are many paths to go down. Certainly, a greater focus on developing one’s own style rather than the need for reassuring approval of peers. An off-beat personal style is no guarantee of quality, I should emphasise; pursued just for the sake of being esoteric or off-beat it would be an empty thing and would be seen through as such in an instant. You’d hope.

But the critical point and the main thrust of this article is that, through practice, many people will arrive at a style that they would never have originally guessed at. Nobody, I guess, gets “into” landscape photography imagining that they will rejoice in forecasts of fog and rain and will feel their heart skip a beat more at the chance arrangement of birches than at dramatic light at an iconic viewpoint, but that really is the case, just as many people learning piano would never guess that the schooling of their ear would lead them to a love of the off-beat rhythms and harmonies of many lesser-known names, and also as many people learning to write poetry wouldn’t even guess at the odd beatnik paths their passion would take them down. But I suspect that it is only by a practice that you reach this realisation of your own voice, which then informs your own tastes which in turn feed back into your own practice; and I would argue that it is when you start to recognise your photographic “voice” (or vision, style, whatever you want to call it) developing that marks a far more profound engagement with the art.

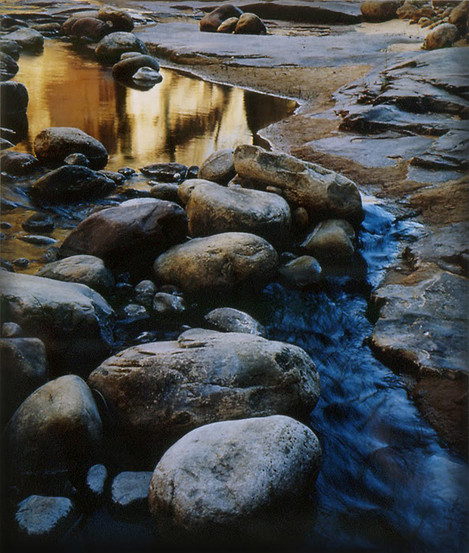

Eliot Porter, “Aztec Creek, Glen Canyon Utah” 1962 . Alluring complexity that holds the attention; subtlety, balance, and a close attention to the colours of the “golden hour”, but certainly not a classic “view”.

Whichever way your voice develops it will probably also involve an appreciation, in new ways, of why (and hopefully how) the Greats are truly great, and perhaps also the feeling that the longer a photo can hold your attention is a better gauge of its merit than the violence of its immediate appeal.

Flat, dull light and unremarkable subject matter, and a film with a restrained colour-palette; good fodder for composition and certainly not a photo that everyone would take or like.

I think a similar thing probably happens if one gets into painting: the immediacy and physicality, the Velvia-like impact of oils are probably the initial tug, but many people will later find themselves pulled towards the more neg-like allure of watercolour or a staccato love of charcoals. (I love Velvia, but you know what I mean.) And everyone painting will probably agree on the greatness of the canonical painters (unless they’re trying to be painfully right-on), but as the practice and individual voice develops some will find themselves pulled against their will in more esoteric directions.

Of course the similarities between the arts are not precise, and I don’t want to strain my case: e.g. many branches of the arts seem not to suffer from quite the same kit-lust (at least not at first), you never hear painters obsessing over the latest sable-haired brush (see below - ed), and for the dancing arts it does seem that the focus on technique must be constant to produce great work. For poetry, it seems that to write in the classical style is just hopelessly fuddy-duddy: does anyone actually write iambic pentameters or sonnets any more? But there is enough to make me think that there is something basic and fundamental in the arts and not just in our art, a progress towards finding one’s own artistic voice in the trajectory that I know many of us have traced.

I know some of you are probably already half way through penning irate comments, so let me end by clarifying and hopefully bridge-building. Self-evidently, my taste is just mine, just as yours is yours; neither is better or worse, more or less refined, and neither is anything but involuntary. For some, bold colours and drama are what it is all about, and you only have to look at the subject matter of any landscape photography magazine or the type of prints that people buy to see that frankly drab, low-contrast and quieter scenes (that I personally have grown to love) just aren’t hot ticket items. But the arts, and our art within it, should be a broad church: there is space for everyone and everyone’s taste, there is certainly no hierarchy in preference. The quest for improvement and refinement is the thing.

(note from the editor - see here for artists discussing mongoose hair brushes)