Rob Hudson talks to Michael Jackson about his Poppit Sands sequence

Rob Hudson

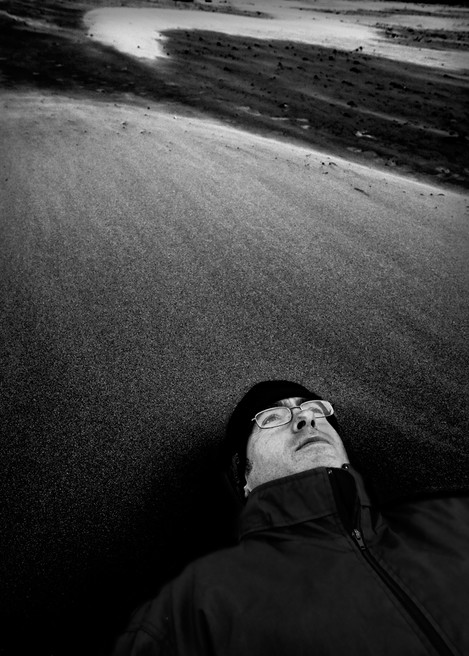

Rob Hudson describes himself as a ’conceptual landscape photographer’ and lives and works in Cardiff, Wales. His work, which is always in series, explores how we relate to the landscape.

Michael Jackson is best known for his 4-year-old (and continuing) exploration of the beach at Poppit Sands near Cardigan in west Wales. That length of commitment, which startles most photographers, is all the more remarkable because his chosen patch is little more than the size of a football pitch. He always uses the same camera, an ancient Hasselblad 500 CM and a 50mm lens that always stays on the same settings.

Michael Jackson is best known for his 4-year-old (and continuing) exploration of the beach at Poppit Sands near Cardigan in west Wales. That length of commitment, which startles most photographers, is all the more remarkable because his chosen patch is little more than the size of a football pitch. He always uses the same camera, an ancient Hasselblad 500 CM and a 50mm lens that always stays on the same settings.

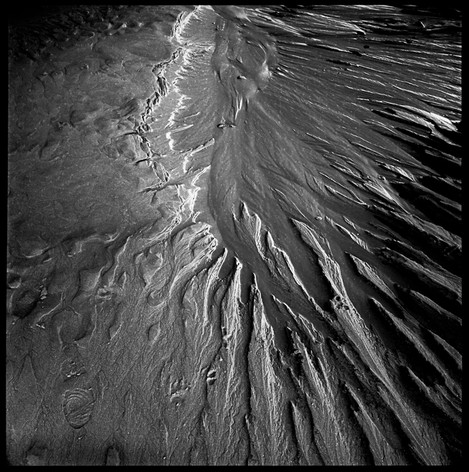

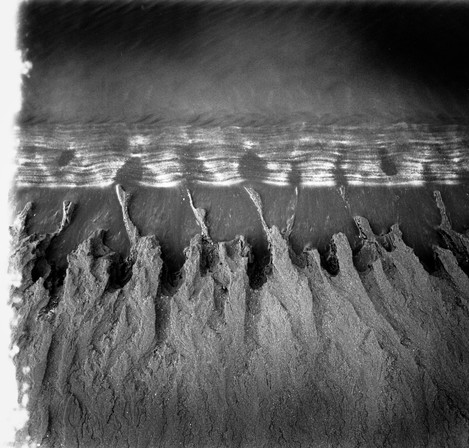

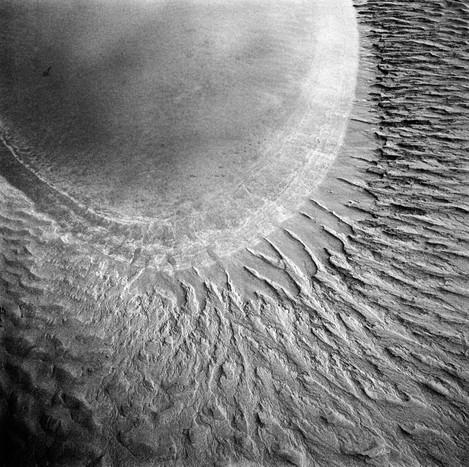

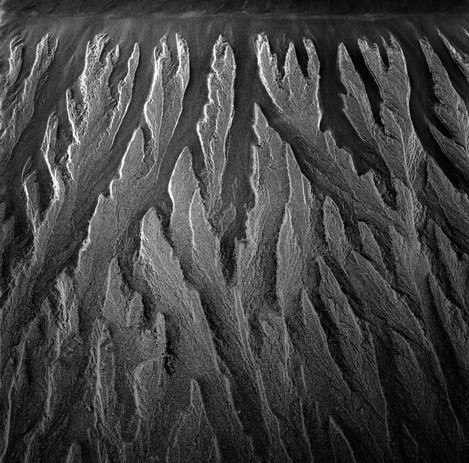

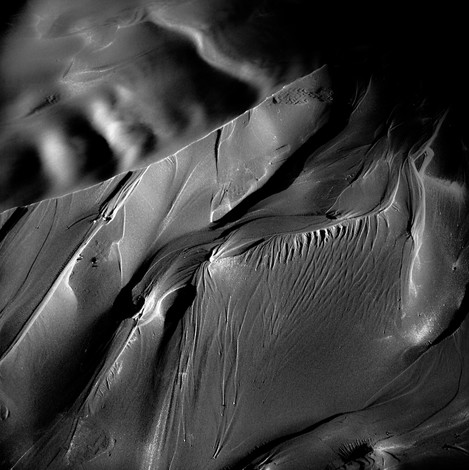

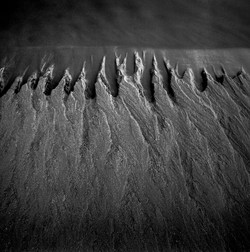

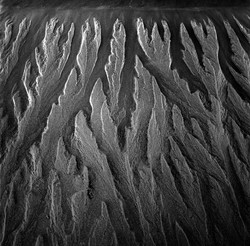

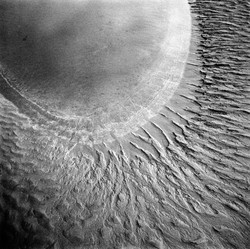

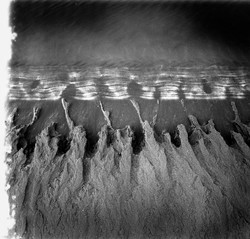

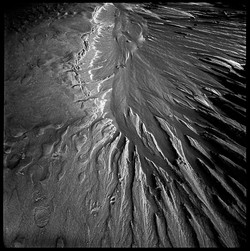

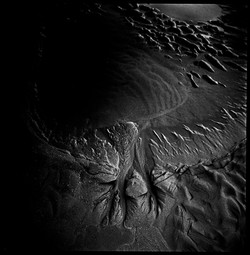

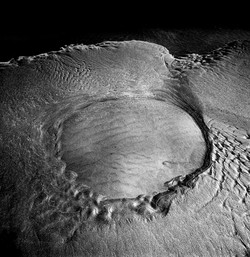

That particular camera has paid dividends in his photographic career. Three years running he has been shortlisted for the Hasselblad Masters Competition for some quite beautiful images; they immediately struck me for their wide range of tones from deep, rich blacks to startling, silvery highlights. There is an otherworldly, almost alien, quality to his work. What you’re looking at is ambiguous, with a tendency to carry you to a different place. Relying primarily on sweeping lines, intriguing shapes and contrasting textures formed by the interaction of sand and water, you could almost think of it like music, a beautiful melody or a song. And that’s not just your author spiralling off into some metaphorical epiphany. Ansel Adams said, “I can look at a fine art photograph and sometimes I can hear music.”

I went to Poppit to meet Michael early in November 2011. I wanted to try to get an understanding of what motivates such a long-term commitment and gain some insight into how he produces such startling and varied images. Pretty soon I was to discover I had found yet another photographer to interview who doesn’t consider himself to be working in the landscape genre in the strictest sense, in that he is producing photographs which almost always exclude the sky. But when asked he also denies (jokingly) being a purely abstract photographer.

“I don’t think of it as abstract. Some of it is, some of it isn’t. There – is that a wide enough answer for you? The Poppit stuff is just pictures of sand and water and the two reacting together. Um, I would say some of it is and some of it isn’t! My deeper answer to the question is ‘yes and no’! (laughs) But I wouldn’t actually think of it as landscape photography.”

He is of course completely right to be hesitant about that particular attempt at pigeonholing. The question has to be asked: whether photography can ever achieve abstraction? Remembering what Ansel Adams said, “In a strict sense photography can never be abstract, for the camera is incapable of synthetic integration.”

He is undeniably passionate about his photography.

“It’s obsessive, I’d say. It’s something that, apart from my family, it’s the main thing that I think about. I’m sure lots of photographers are the same. It’s something that registers really high on the levels of need, that they’ve got to come out and take photographs. It feels like a drug to me, you get a real physical high when you see the images.” Yet despite that fervour, he considers his work as something of a “scientific experiment”, like “looking down a microscope or telescope”, but his technique he describes as non-technical “I don’t think of myself as a technical photographer, I don’t fiddle around with the settings on my camera at all, they are always on the same settings.” Not once did I get the feeling these were in anyway contradictory to Mike – more that he is both unpretentious about his work, and he has that essential mixture of artist and scientist that produces some of the best photographers.

Before coming to Wales Mike had worked in IT, becoming increasing obsessed with the world of art; even studying to be a painter.

“It got to the stage where I would get to work and spend all day thinking about painting. I started studying under a painting teacher called Chris Baker, he was so inspiring, it was fantastic. I’d just listen to every single word he’d say and take it all in. In the end, I asked to be his apprentice. I’d do anything to help, just to see what the day-to-day existence of an artist really is, because that fascinates me.” He migrated to charcoal portrait work, but he soon discovered photography, buying a Holga and a developing tank. “One of my first shots was of my dog and I just couldn’t believe it, it made him look like an angel! It was amazing – it was all blurry, beautiful light. I didn’t really know what I was doing taking photographs, but it kind of sparked something in me and I stopped doing all my charcoal and just kept on with the Holga.”

“Coming to Wales was a big choice for me and my now wife. We wanted to have a lifestyle we could build around my photography. I’d had enough of IT, I wasn’t getting out of life what I wanted, but I was [getting it] out of photography. It’s probably very naïve. I probably didn’t know all the facts, but because I didn’t know the facts it probably didn’t scare me off as much as it would have done had I known how hard it is to make a living as a photographer. I didn’t know anything about Poppit Sands then. I spent a couple of months going around the whole area taking quite standard landscape photos and taking them to galleries and asking, ‘what do you think of this, then?’ Luckily one of them was in Cardigan, he looked through them and really liked them and he suggested taking shots at Poppit Sands. I came down and the first time I took some photos I really fell in love with the place. It was the first time I got a certain type of light and image that I wanted. It was something about the blacks and the silvery tones at that time of day at low tide that made me think, ‘This is it! This is the type of photograph I want to keep on taking.’”

Eventually migrating via a Mamiya to the Hasselblad, he became increasingly fascinated by the darkroom process and ‘flying the flag for film’. “I develop it at home. I scan it into Lightroom, at the moment. I’m working more and more in a darkroom, but it’s such a steep learning curve. I find the darkroom printing exciting, for me it’s strange to go through all this process of working with film and developing it by hand, having it all tactile, touching it and smelling it, scanning it in and pressing a button to print it out, it seems like a funny ending to me, a bit of an anti-climax.”

One of the things about landscape photographers that intrigues me is their connection to a location, be it through a sort of personal history or an abiding affection built over time. I wondered if Poppit was special, important? “We come here with the family, but not really, no, I don’t get shivers down my spine when I walk on it. I’ve been coming here so often, that when I trudge onto the beach it almost feels like going to the office. I get quite possessive about it because you get people walking their dogs and horses. But it definitely feels like a workplace rather than a place to go for pleasure. You go there for a reason because you want to record what’s going on. You want to capture these moments. It’s when you’re walking from – that you see the geese flying over – that’s when I take it in. But once you’re concentrating, that’s when you’re looking all over the place to try and see where you are going to shoot, I think it’s interesting how your mind can channel. You get tunnel vision in a way and you can just ignore everything else.”

Maybe the creative process itself provides his inspiration, while he’s out on the beach? “Um, I find it a bit, um, hard, ha! I don’t find it relaxing, I don’t find it fantastically enjoyable. I do find it exciting when I think that I’ve found a new shape or a new texture, but I’ve nearly always found those times when I am excited about it, when I’m patting myself on the back, when I get it home it nearly always turns out to be a disappointment. It’s the ones that I just thought, ‘yeah, that looks all right,’ those ones are the ones that surprise you when you get home. “

“I like variables, like making mistakes. Quite often when I’ve made a mistake developing, or when I’ve left my footprints in some of my photos I thought that would completely ruin it, but now I’ve come to really like having mine and dogs’ footprints in there. I find it adds extra focal points. I think your eye goes straight to the footprint – well, mine do. It makes you look at it first and then leads you into the rest of the picture. I’ve come up with a theory about focal points and I think if there’s more than one focal point, then it makes it more interesting. For some reason in my mind, when you look at it makes it makes a more interesting picture than if the footprint wasn’t there.”

So does he have influences, people, ideas, inspirations, anything behind it? “Not Poppit Sands, I can’t think of any influences at all. It’s just from me really. I didn’t see someone take a picture of a beach and say that’s how I want to take pictures of the beach. It just seems to have progressed over the years. It surprises me that I don’t see more people doing it, it surprises me I don’t see other people on the beach taking photos. I just don’t understand why some photographers don’t want to try something new, or maybe why can’t they just do photography in a similar style to other peoples work if that’s what makes them happy? Who am I to criticise and say you don’t want to be doing that?”

“I sometimes feel there’s a lot of self-promotion involved with that type of stuff and sometimes people do over self promote themselves. It’s not in my nature to tell anyone how they should do anything, but it’s a shame some people don’t seem to get past a hurdle. They see photographs taken by Joe Cornish and Charlie Waite and they think ‘brilliant, that’s what I’m going to do, but they never seem to be able to produce photography that’s as good as those two, because they have crafted a style that is theirs and comes naturally to them and they’ve got the eye that allows them to carry on producing such a high grade of work. People like Joe Cornish and Charlie Waite have spent a long time building it up and they’ve made lots of mistakes. They know the way to think about producing an image – the thought processes and technical processes are just tuned in. It’s no wonder they take the Joe Cornish image and think how fantastic it looks, try and replicate it up to a certain point, but because they haven’t taken the process to get to that point, they don’t continue the journey. They stick with taking that style of photo for the next 20 or 30 years because they haven’t artistically grown to get to that point. It’s about being honest to yourself. I went through a Charlie Waite thing right at the beginning, which is the reason I got the Hasselblad, I saw him take some fantastic photos and I got some of his books. There was something special about the light in them, there’s something uniquely special about what he does.”

I’m fascinated by why photographers choose to work in projects, committing in this case many years to one subject. I ask Mike why does he work in projects? What does it add to your work?

“I like the idea of repetition. I always have liked the idea of repeating something over and over again – be it Poppit or be it taking photos in Cardiff in a certain way, going to the same place again. “

Is there a developmental aspect, be it only incidental? Poppit has surely changed over time? “It has. It’s easier to package up I suppose, it’s easier to monitor, and it’s easier to think about when you’ve got certain boundaries. Like Skirrid Hill, it’s probably easier for you to work on a book of poems from the same person, rather than work on a different poem from half a dozen different poets. Especially with Poppit – the more you go, the more you see. The landscape of the sands changes all the time, every time you go there you see something different. You can keep on going back there, and back there, and back there, and it builds up and becomes more meaningful to you. You begin to do things in your subconscious rather than having to think about them. You can only get that from repetition, I think. If I was to go from beach to beach to beach to beach, I would start to get a little bit confused, I wouldn’t be able to channel everything and condense my thoughts about the way I want it to look.”

“I find so many ideas lead to dead ends. You can waste an awful lot of time trying this new great idea, when you finally realise that what you are doing is copying someone else. That sparks off an idea in the back of your head. Compartmentalising all these different projects and managing to control them, rather than scattering lots of different things. It probably comes down to your personal nature, the type of person you are, the way your personality shines through your photography by the way you structure going about doing it. Not necessarily the style of the photo, but what’s built around it. I think I might be a bit obsessive about projects, I don’t think you have to be obsessive, but I think you have to have a passion about a single subject enough to keep on wanting to do it. I think you have to be the type of person that can have that kind of a passion without being distracted. Keeping it with strict boundaries, instead of scattering everywhere, means that you are condensing the way you think and making the message that you are sending stronger. If someone can come along and do landscape photography in a way that when you saw their photo that you would know it was them, then I think that would be a wonderful thing. Surely that must be an expression of how much personality that person has put into creating that photo?”

“I was trying to water down into just a few words what photography is. You can say it’s simply a way of communicating an experience or an emotion, you are sharing a memory, something that you’ve seen with other people. You can apply that with landscape photography, because they’ve seen this fantastic sunset or landscape and what they are doing is capturing it either for themselves or to share with other people. Really you’re doing it for yourself. I’m doing Poppit for me, rather than everybody, so maybe it is a personal project. Goodness me! I’m finding myself!” (laughs)

I reflect on how such a creative and distinct photographer fits in with current landscape photography, and what state he finds it in? “That’s a good question! I don’t see very much of it to be honest, I don’t buy magazines or anything like that. It seems to me in this country there’s a certain type of landscape photography, in America, it seems to be a little bit different. Maybe it’s Ansel Adams? I find it very difficult to have a strong opinion about that. I find that if you try and tell someone how they should take a photograph and say, ‘Look, that’s a cliché’ – it’s got a purple sky and there’s some rocks in the foreground – you’re kind of telling them what food they should like. It’s totally down to them and totally their opinion. I try not to look at other photographers too much. I’m a bit like a sponge, and it pushes me off in different directions that I don’t really want to go. I find they were doing it better in the first place, and why on earth copy someone else? The amount of time and effort that I’ve invested in going in that direction, it’s like a dead end.”

Many photographers tell me how they like to “tune in” to a location before undertaking creative work, that’s when they say they produce their best work. Does Mike have a “strategy” for finding creativity? “No, no, nothing at all. I used to when I started, I always used to listen to the same piece of music – Philip Glass's Koyaanisqatsi. I always used to play it driving to Poppit and driving home, and when I was developing the film. I find a lot of people find when they are commuting that they use driving as a relaxation, a way of separating home from work, and Poppit is kind of a workplace for me. Then I used to think, ‘this piece of music is becoming essential to my way of photography, I bet if I don’t listen to this piece of music I won’t be as creative on the beach.’ And then one day I forgot the CD and went down there and got a couple of good ones – and hallelujah! I still love listening to it, but now I find it’s not something that I need to listen to get into that state of mind.

“I usually find that when I get onto the beach I’m in a state of strange panic. I’m looking around, I’m not relaxed in any way at all, because I’m really worried that I’ve missed the light, or I’m really worried that I’m not going to get anything. I’m really worried that that dog is going to knock my tripod over. It takes me about 10 or 15 minutes before I start to relax. I’ve lost count of the number of shots that I’ve cocked up, the number of times that my lens has jammed – I’ve got through three lens services since being in Poppit – because I use the same lens all the time. I’m on my second tripod and second camera bag now, because they just get gunged up. I find that, because I only take three rolls of film with me, that if I get there too early, I’m so keen to start taking photos, I start snapping away at things that aren’t really worthy of taking photos of and I find – hang on a minute – I’ve got no film left. “

Many well-known photographers cite a past as a painter or an art practitioner as an influence on their work. Many photographers made the switch from painting to photography, from Eugene Atget, Cartier-Bresson, Lartigue, Mapplethorpe to today’s Chris Friel and David Unsworth. Ansel Adams also cited his past as a musician on his work. Mike trained as a painter; I ask how does that influence his work, and should photographers study art? “What kind of art it comes out from within you without the need to study. Studying art may have helped me with composition, but if anything it gave me a love for the process that an artist takes. Not specifically painting, but the way he lives his life – in a frugal way, not needing expensive things and being able to devote yourself to your art. I draw most of my inspiration from art like Andrew Wyeth, but it doesn’t inspire me to go out and take pictures like an Andrew Wyeth painting. You can be inspired by them, but you can’t copy their style. You can be inspired by how they lived, and what they had to say, and how they dealt with the day-to-day artistic way of getting around things, how bold and noble they were to go out and do what they did. You can admire them without the baggage of thinking, ‘If I incorporated some of his work into how I do my work, maybe what he got will rub off onto me.’ Maybe it’s because I’m a bit older, when I was younger I wanted money, flash cars, but it’s almost like I’ve found satisfaction in something that I can get. I think you can enjoy technology and enjoy being an artist as well, but I have no desire for money – the strange thing, now it doesn’t really matter. It’s to be able to follow a photographer’s lifestyle and to be able to work on it all day, every day.“

Mike switched from charcoal drawing to black and white photography. I wonder what intrigues him about monochromes and why he disavows colour? “I don’t think there’s anything wrong with colour, but to be completely honest I couldn’t process colour film at home. The colour photography that I’ve tried just doesn’t do it for me at the moment, but I’ve got a feeling that I’m going to experiment and try things out. I’m finding at the moment that I’ve got so many things that I’m trying to wrestle with and learn in the darkroom. That’s just taking up all my time at the moment. I’m hoping split toning will get some colour into the Poppit stuff, but not natural. One of my main influences for Poppit was the Apollo shots and that’s all very monochrome-looking. For me, colour doesn’t fit in, but it might come. I’ve found something that I love and that satisfies a need in me like a drug so I’m sticking with it. I’m working with that in a constrained way.”

I’ve heard and read many times about the influence of lunar photography on Mike’s Poppit Sands work. Is that purely a personal motivation, or is it an attempt to increase the appreciation of the viewer? “Certainly not the second! I think it just puts a pointer in my mind as to what I’m trying to achieve. Ever since I was very young I’ve always loved pictures of the craters, the way the angle of the light hits the moon, and I could look at pictures of the moon forever. That childhood passion is coming out with the way that I make the Poppit shots look. But it really does look like the moon out there. It’s not playing around with Lightroom, there’s a certain slot of time when the light is in a certain way and it just comes out like that.”

So why did he choose abstraction as a method of photographic interpretation and (joking) what the hell is wrong with the sky(!)? “There’s nothing wrong with the sky! (laughs) I do take pictures of the sky, but it’s when it’s reflected in the sand and water. When I first started at Poppit I did those classic ‘landscapey’ shots, but I found there’s a limit to how much you can do. For me what was really going on, what was really changing was… pointing downwards. I found gradually that my camera was gradually pointing further and further downwards until the sky was wiped out altogether, apart from the reflections in the water. And then it gives you a free rein. When you are finally pointing downwards you’re not stuck with the structure of the headland behind you and a certain amount of sky or whatever. You can just go completely crazy and shoot in any direction you want, and not have to worry about it being perfectly level, or the sun hitting the clouds in a certain way. If you are pointing downwards the sand gets wiped clean every day and new formations come. It’s just limitless the amount you can get out of it.”

You’ve split the Poppit Sands work into galleries by period on your website. Why is that? Is it editing? Allowing bite-size morsels? Or has something changed over time? How does time influence the development of a project this long? “I think it’s changing over time, but that’s not the reason why. I put it into different galleries so that anyone who wants to see the newer stuff can go to that gallery. I look at in terms of 10 years, 20 years – it’s not a short-term thing. It’s that fact that makes me take a slow and methodical approach to it. Things change very slowly, they feed off each other, one change feeds off another change, feeds off another. Poppit Sands is changing. It changed from being standard landscapes back in 2007 to abstracts. It seems to be getting darker and footprints are becoming more prominent in them. “

Has the framing become more “active” recently, closer; more likely to hint at what’s outside the frame? Is that a conscious decision? “What I’ve started doing is using full frame cropping, I’ve made a conscious decision not to close crop things. It’s no snobbery saying I don’t have to crop my photos, it’s almost like some kind of discipline. Partly because I like the aesthetic look of the black around and also because I’m now using the enlarger in the darkroom rather than the scanner. You can get those lovely rough edges.”

The more recent work strikes me as both being somehow more defined in its shapes, and hinting at shapes which are more open to interpretation – more alien, more sci–fi, if you like. Have I just been looking too long? “Really? That’s good, that’s a compliment, I like the fact that it’s, err, strange. I like it when people say they are strange images to look at. You could say it’s a pretty image, that’s all right, but if you say it’s an unusual image or I’ve never seen anything like that before, then that’s brilliant!”

A certain well-known photographer (who shall remain nameless) described Mike’s work to me as “beautiful, but meaningless”? Which I suspect is something of a key point in my appreciation of his work. I need to understand how and why my intellectual side can appreciate something which is essentially empty of meaning. How come I find it so satisfying? “He’s probably dead right! I dunno when you say ‘meaningless’ – what does he mean, what does it mean to ‘mean’ something? I don’t understand. Photography is totally subjective and what I’m trying to do is show something that I like the look of. It’s as simple as that, I’m not trying to have any other kind of meaning really. If someone can say it’s beautiful then that’s good enough for me. Photography should be like standing next to the photographer. It should be like them talking to you, it should be like them saying to you, ‘Look at what I’ve seen, isn’t this lovely?’ To me, if I look at a photograph I want to feel like the photographer is there, pointing out these particular aspects with the camera that they fell in love with and it’s wonderful enough to share. For me it’s the mixture of tones, it’s satisfying and is something that I love to look at. Maybe it’s because I purposely don’t try to put any meaning in it at all. Throughout all the photography I do I’ve tried to keep it as simple as possible. I remember going back to the painting and thinking about how I got myself tied in knots, mentally, reading about what artists think of this and artists think this way and it completely sent my head into turmoil. So that’s why I try to keep it pretty simple. I have a theory that you should be able to tell if you like a photo or not from looking at it through a shop or gallery window. You should be able to tell straight away whether you thought it was a nice structure or whatever.”

Maybe the answer is in that ambiguity? It is the vagueness of that “abstract” nature that gives us licence to engage, to open our minds to the simple beauties of shapes, tones and textures. The art lies in the question, not the answer. An “answer” in photographic terms is all too easily digestible. As landscape photographers we all have a natural habit of telling the viewer what they are seeing – sky, rocks, grass, composition, etc. The questions raised by Michael Jackson’s work are too intriguing to be easily discarded. They demand attention, and art requires first of all a personal engagement, an investment on the part of the viewer, an exchange of ideas, a cross- pollination of emotions. It’s what John Blakemore (when discussing a sequence) described as “the construction of a meaning that transcends subject” and that “meaning is formed in the space between the viewer and the image”.

Within that ambiguous world, we can appreciate the art in a work. I can’t say I can actually hear music when I look at Mike’s work, but the emotions they evoke are the same as listening to a treasured classical composition. Patterns from sweeping harmonies, the circularity of melody, the patter of a timpani and the boom of a big base drum, all are to be found there. And it’s the sort of music I don’t want to finish, I ask will the Poppit Sands project ever end? “I fully intend to do it for the rest of my life.

You can see more of Michael Jackson’s work on his website http://www.mgjackson.co.uk/