Master photographer

Tim Parkin

Tim Parkin is a British landscape photographer, writer, and editor best known as the co-founder of On Landscape magazine, where he explores the art and practice of photographing the natural world. His work is thoughtful and carefully crafted, often focusing on subtle details and quiet moments in the landscape rather than dramatic vistas. Alongside his photography and writing, he co-founded the Natural Landscape Photography Awards, serves as a judge for other international competitions. Through all these projects, Parkin has become a respected and influential voice in contemporary landscape photography.

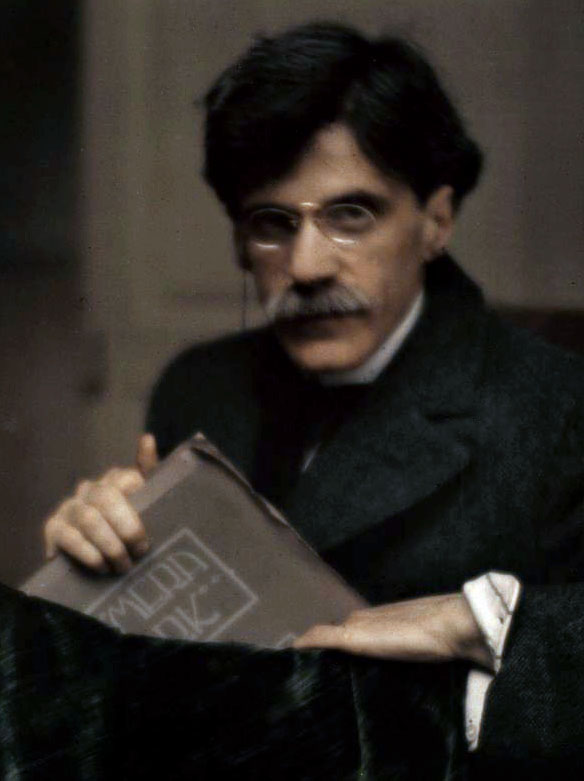

When his family returned to America, Alfred started studying under Professor Hermann Wilhelm Vogel. Prof. Vogel taught metallurgy and chemistry and gave the course in photochemistry that Alfred studied. Vogel challenged Steiglitz to make a photograph of a white stone statue outside with a black velvet cloth draped over it and retain detail throughout. Alfred surprised his professor who thought this was not possible.

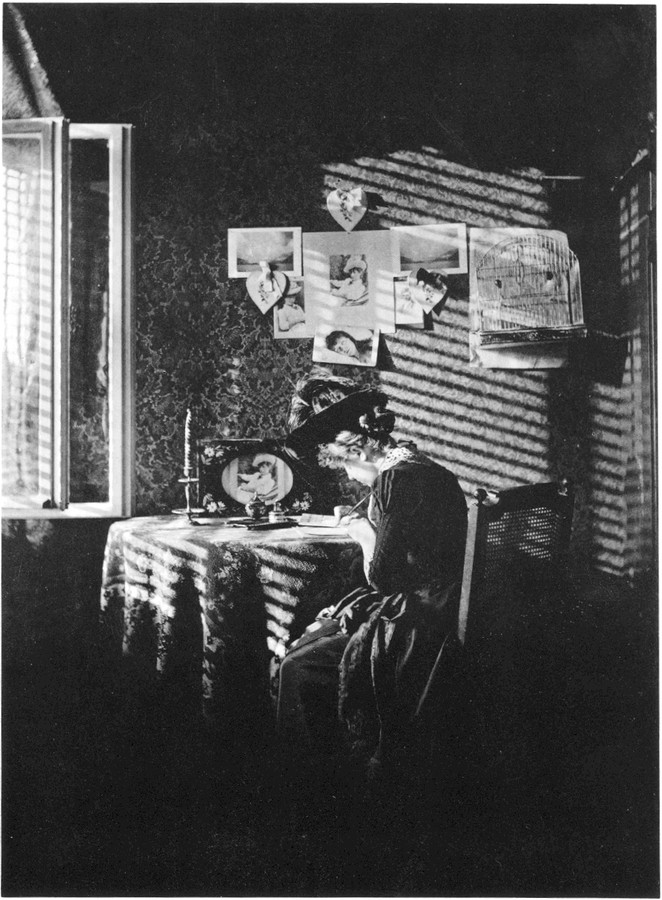

At this time, Stieglitz was also taking landscape photographs in the Alps, particularly photographs of Lake Thun with a sky that foreshadows the equivalents series. Stieglitz was finding a place for himself in Europe and was exploring some abstract concepts of water and clouds (if approaching them askance) and he also had a romantic involvement with a prostitute who ‘starred’ in one of his most successful images of that time, “Sun Rays, Paula”.

He was called home at the death of his sister and he was so attached to his European life that he refused until his father threatened to stop his ‘stipend’. Stieglitz found New York ‘difficult’ after the liberal life in Europe; a drab city without the cafe culture and without a network of friends, he found it lonely. He started making contacts quickly though and was quickly writing for it with ‘A Plea for Art Photography’ - a call for simplicity and boldness in composition.

It was at this point that Stieglitz borrowed a hand held 4x5 Kodak plate camera* with which he took a picture that for him became ‘The basis of so-called “American Photography”’ - “Winter, Fifth Avenue”. He subsequently bought a Graflex which he loved so much he contributed testimonials to the company. With this camera he very quickly took another pivotal picture, recalling his earlier images of draft horses in Europe, “The Terminal”.

Over the next year he worked taking pictures around the streets of New York and Central Park. The following year he made a marriage of convenience with a friend of the family, Emmilie Obermeyer - a marriage that was not consummated for another year and one that Stiegletz regretted almost immediately.

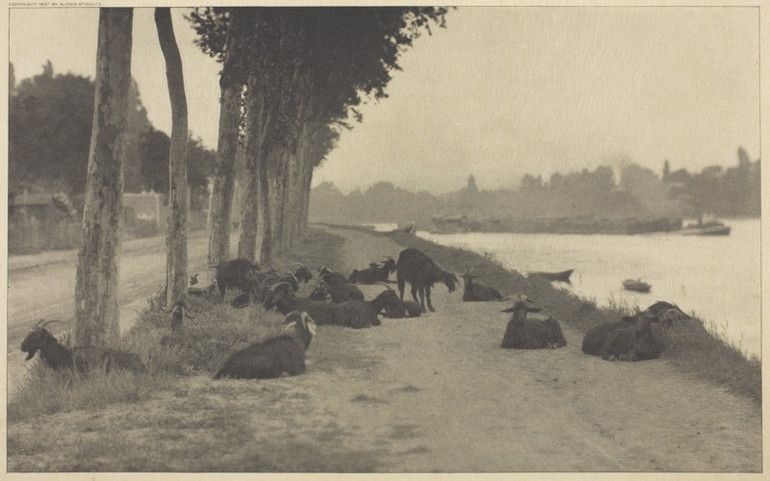

They honeymooon'd in Europe where, in Paris, Stieglitz took another significant picture of the wet streets, “A Wet Day on the Boulevard, Paris”, the subject being a sense of luminosity rather than the descriptive city scene. Another image that shows a wonderful sense of composition of line and shape was “One the Seine - Near Paris” where a drover rests with his goats but where the image is a combination of perspective, line and recession.

Whilst he took many distant views of the mountains, one of my personal favourite pictures was of a mountain bridge (called “Mountain Bridges”) which depicted two bridges over a gorge but displayed a sense of shape, texture and weight that is quite admirable.

Whilst travelling in Venice, he also took a striking image of the canals, exercising his control over contrast creating luminosity in the sunlit and shaded parts of the picture. A subsequent crop of this image was also very strong and was a little more suggestive than the more classical un-cropped image.

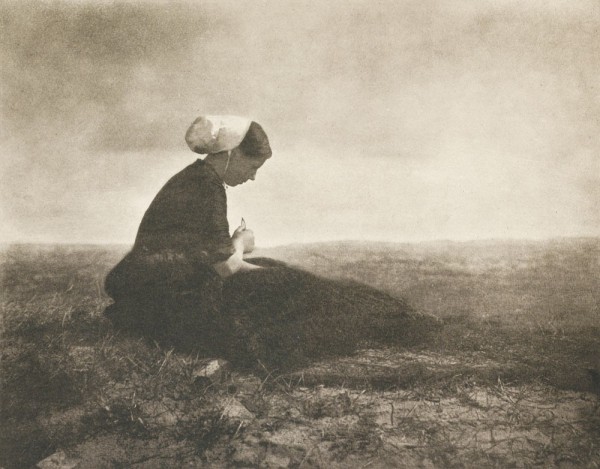

Stieglitz was still working in a pictorial sense though although his work in this genre could still be revelatory. In particular, a photograph ‘The Net Mender’ is particularly evocative and demonstrated Stieglitz’s empathy with the rural and the honest toil involved in village life, an empathy reflected in his work on the streets on New York.

Two other images were taken in Katwyk (the location of the Net Mender) were also significant. “Scurrying Home” is the better known photograph but “The Gossip” with its daring balance of composition is another of my favourites. Interestingly, Stiegletz was travelling around the ‘iconic’ locations of Europe (Venice, Paris and Katwyk particularly being a subject of many painters including Turner).

On his return, Stieglitz became a whirlwind of activity, helping merge the New York camera clibs into a single entity and becoming president thereof, becoming a member of the Linked Ring brotherhood and becoming editor of Camera Notes (the united clubs periodical).

Stieglitz could be as annoying as he was inspiring though and rubbed many people up the wrong way. When the workload became too much and he invited two non-members of the camera club to become assistant editors which ‘annoyed’ some of the other members who made efforts to expel him from the club. Fighting this, whilst running the magazine, exhibitions, etc. mean that this wasn’t his most productive years photographically. He did meet a long time best friend in Edward Steichen, a photographer who began in painting which, in Steiglitz’s mind, gave him an authority that was complementary to his way of thinking. Stieglitz said, “I think I’ve found my man!”.

Stieglitz had a daughter at this point on whom he swung between dotage and disregard. This was the turn of the century though and Stieglitz had other interests. He began the century by putting together an exhibition by the ‘Photo Secession’ a group of photographers chosen by photographs - an uncommon thing at the time. The secession was a move away from the attempts to make photography like painting and an attempt to allow it to be itself.

The same year he officially resigned from Camera Notes and started Camera Work, a journal of photography and art with the goal of placing photography firmly alongside other artistic media. He also opened a small (very small) gallery that complemented the periodical and was used to promote photography and as a place to show the latest movements in art as well (The Little Galleries of the Photo Secession)

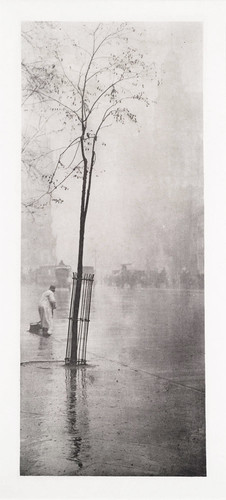

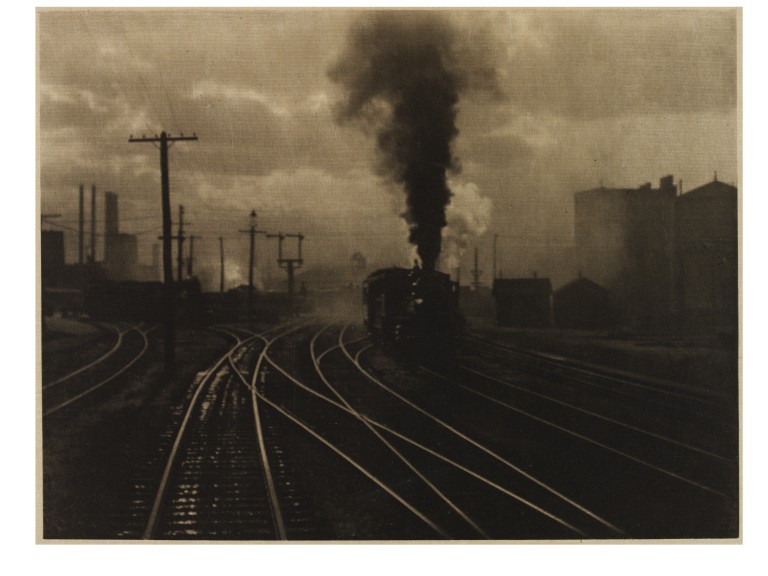

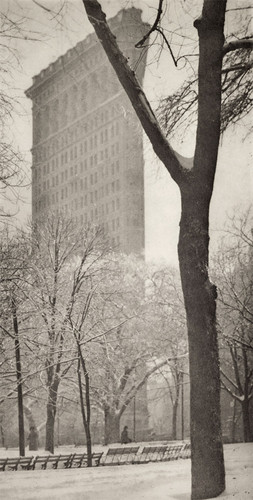

In the first three years of the 20th Century, Stieglitz made up for his lack of work in the previous years by producing some of his best work. These include”Spring Showers” recalling his Paris rain pictures, “Snapshot from my Window, New York City”,“The Hand of Man” and “The Flat Iron”, marking a sea change in photography.

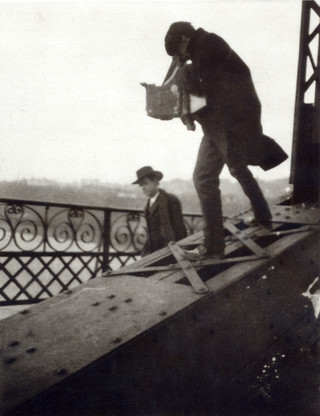

These images were a prologue to the photograph around which his work would pivot. On a trip to Europe, he was drawn to an arrangement of mechanical and human shapes and produced “The Steerage”.

Between 1907 and 1915, Alfred Stieglitz became a colour photographer. Yes, you heard that right. He was playing with the autochrome process. Just like Ansel Adams experiments in colour, this was merely a sideline, an experiment of sorts and although some images were strong - they were merely black and white images in colour and did not use colour in any particularly creative way.

Over the next decade, the gallery changed name to 291 (its location on Fifth street) and featured photographers such as Edward Steichen, Paul Strand, Alvin Langdon Coburn, Robert Demachy, Constant Puyo, René Le Bégue, Gertrude Kasebier and Clarence H. White and other artists such as Henri Matisse, Auguste Rodin, Henri Rousseau, Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, Constantin Brâncuşi, Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove, John Marin, Charles Demuth, Georgia O'Keeffe, Francis Picabia and Marcel Duchamp.

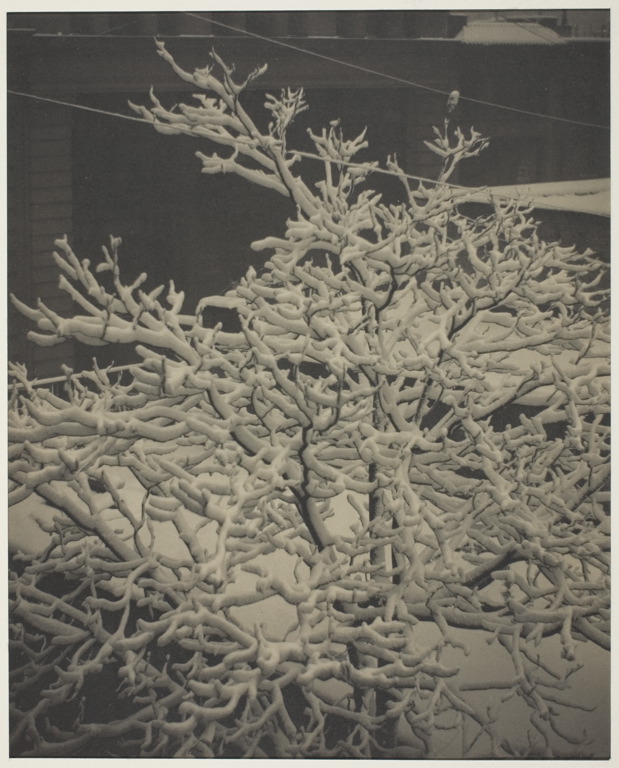

He also produced work that echoed "The Steerage"s new approach, including some from the back window of the gallery! ("From the Back Window of 291" & "Snow Covered Tree, Back Yard"). He also photographed the dawn of the age of flight with photographs of early aeroplanes and dirigibles.

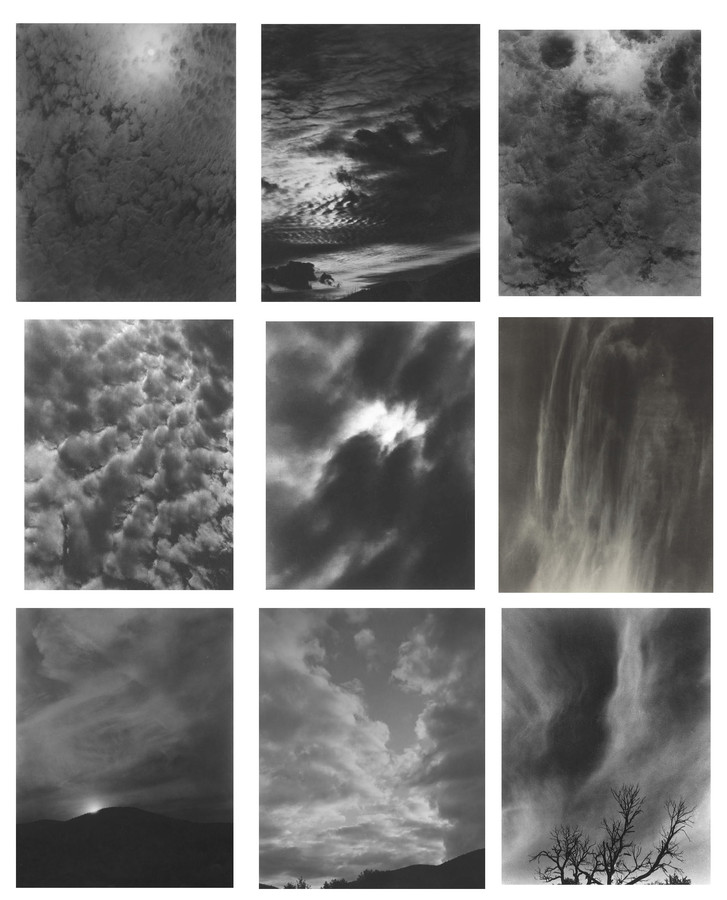

The photographs that many know Stieglitz for are his 'Equivalents'; abstract photographs of clouds. These images were symbolist in nature (symbolism being an extension of romanticism where a shared iconography is replaced by personal metaphor). Stieglitz took cloud photographs over much of his life, starting in Europe in the late 19th century and continuing well into the 1920s. The particular challenge of shooting clouds at the time was that the orthochromatic film was not sensitive to blue light and hence clouds appeared against a white background. The artistic challenge was to answer some of his critics that suggested his photographs were great because of the subject matter, not his particular skill. His answer was to choose the most democratic subject he could think of. The other success of the series was that no one had taken photographs of 'nothing' before, just to present an abstract form from a representational palette. At the time the pictures were revolutionary and received enormous critical praise.

Stieglitz's marriage finally ended shortly after with many people suggesting that he arranged for his wife to find him photographing Georgia O'Keefe naked in their family home upon her return from holiday. This 'provocative' behaviour was not unlike Stieglitz who had a passive-aggressive personality but was also quite prone to just aggressive on occasion. His relationship with his friends was volatile and he gradually pushed most people away from him, including Paul Strand whom he famously insulted after Strand had arranged to invest in a gallery for him.

Stieglitz obsessively photographed O'Keefe over the next decade but still found time to develop further infatuations with young artists. famously Dorothy Norma when she was 42 years younger than him. At the same time

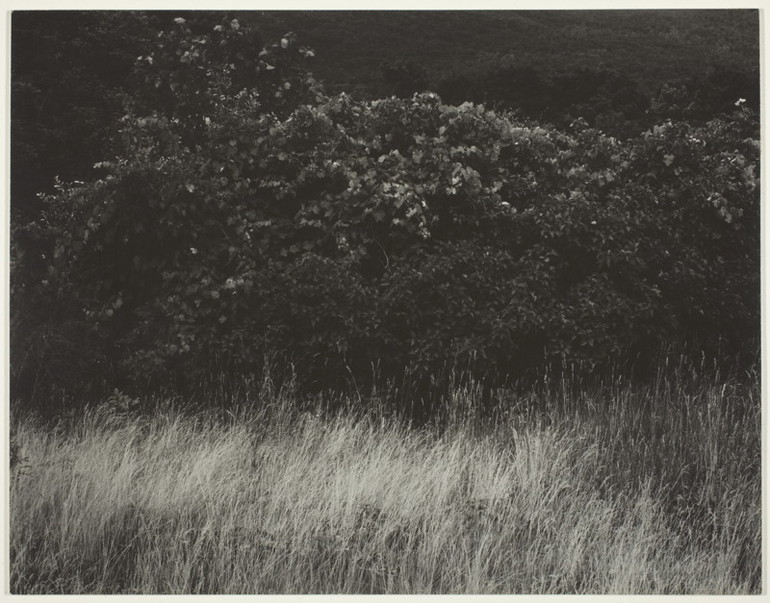

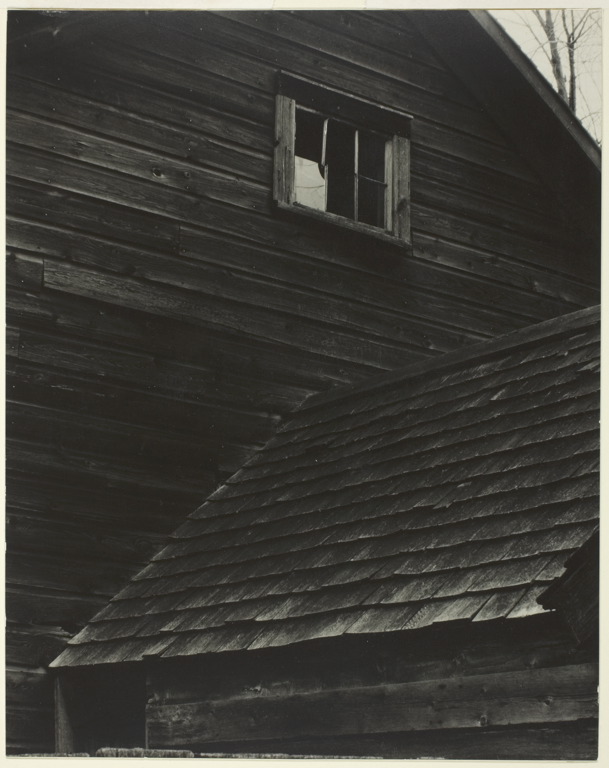

In later life Stieglitz was to shoot landscapes of various sorts, especially around Lake George - a childhood favourite retreat and a Stieglitz family home. The photographs here include beautiful abstract images of grasses.

During his seventies, Stieglitz put on exhibitions of Ansel Adams' work and also, through successfully exhibiting and critiquing his work, nudged Eliot Porter into becoming a full time photographer. Ansel Adams has always talked of Stieglitz as a major influence on his work, being especially moved by the Equivalents series.

Stieglitz died in 1938 after a series of progressively worsening heart attacks.

Timeline

1881, aged 17 - Family moved to Europe for education and Alfred’s father to paint

1884, aged 20 - His family returned to America

1887, aged 23 - Writes for photographic magazines and wins prize with A Good Joke

1890, aged 26 - returns to America for his sisters funeral

1892, aged 28 - Buys his first hand-held 4x5 camera, takes “The Terminal”, “Winter Fifth Avenue”

1893, aged 29 - Marries Emmeline Obermeyer

1894, aged 30 - Honeymoon in Europe

1896, aged 32 - Merged NY camera clubs and became president (Camera Club of New York)

1899, aged 35 - Mental breakdown through overwork and resigned/expelled from Camera Club and editor of Camera Notes

1900, aged 36 - Met Steichen

1902, aged 38 - The Photo Secession is formed

1903, aged 39 - Camera Work issue One

1905, aged 41 - Steichen talks Stieglitz into starting a gallery on Fifth street

1906, aged 42 - First exhibition of Little Galleries of the Photo Secession (291)

1907, aged 43 - Exhibits Pamela Coleman Smith’s paintings, widening his artistic eye beyond photography

1907, aged 43 - ‘The Steerage’, taken on a trip to Europe

1915, aged 51 - Exhibits Paul Strand’s work at 291

1916, aged 52 - Includes Paul Strand’s work in Camera Work / Meets Georgia O’Keefe

1917, aged 53 - 50th and Final issue of Camera Work and last exhibition at 291

1918, aged 54 - wife finds Stieglitz photographing O’Keefe in the nude in the family home - not good..

1922, aged 58 - Reviewed Edward Weston’s work

1923, aged 59 - got a bit naughty with Paul Strand’s wife

1924, aged 60 - Started using a room at the Anderson Galleries (The Intimate Gallery or "The Room")

1924, aged 60 - Marries and exhibits with Georgia O’Keefe

1925, aged 61 - puts on the “Alfred Stieglitz Presents Seven Americans: 159 Paintings, Photographs, and Things, Recent and Never Before Publicly Shown by Arthur G. Dove, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, Charles Demuth, Paul Strand, Georgia O'Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz” show

1927, aged 64 - Starts affair with Dorothy Norma (aged 22)

1929, aged 66 - The Strand’s invest in a new Gallery space for Alfred (The American Place or "The Place")

1929, aged 66 - Georgia O’Keefe gets her own back by being a bit naughty with Paul Strand’s wife too

1936, aged 73 - Put exhibition of Ansel Adam’s work and afterwards, Eliot Porter’s

1938, aged 75 - Heart attack, the first of many which gradually debilitated him