David Ward suggests a good read

David Ward

T-shirt winning landscape photographer, one time carpenter, full-time workshop leader and occasional author who does all his own decorating.

I recently spent a few happy hours searching for photography books in Hay-on-Wye, the second-hand book capital of Britain. On previous visits very little of interest has turned up, despite searching for hours through the racks – it’s strange how searching when we can’t find anything that fits our criteria seems interminable but browsing takes on the aspect of an exciting hunt when we catch sight of even a small amount of ‘game’. This time, however, I definitely struck it lucky. Virtually every bookshop that I went into had a few interesting titles. My haul - an appropriate word as my arms were brushing the ground by the time I finished - included a number of books that I’d never even heard of before (of course this might just be a measure of my ignorance): “Ansel Adams, New Light”, “William Henry Jackson, Framing the Frontier” and “Timothy O’Sullivan, America’s Forgotten Photographer”.

I recently spent a few happy hours searching for photography books in Hay-on-Wye, the second-hand book capital of Britain. On previous visits very little of interest has turned up, despite searching for hours through the racks – it’s strange how searching when we can’t find anything that fits our criteria seems interminable but browsing takes on the aspect of an exciting hunt when we catch sight of even a small amount of ‘game’. This time, however, I definitely struck it lucky. Virtually every bookshop that I went into had a few interesting titles. My haul - an appropriate word as my arms were brushing the ground by the time I finished - included a number of books that I’d never even heard of before (of course this might just be a measure of my ignorance): “Ansel Adams, New Light”, “William Henry Jackson, Framing the Frontier” and “Timothy O’Sullivan, America’s Forgotten Photographer”.

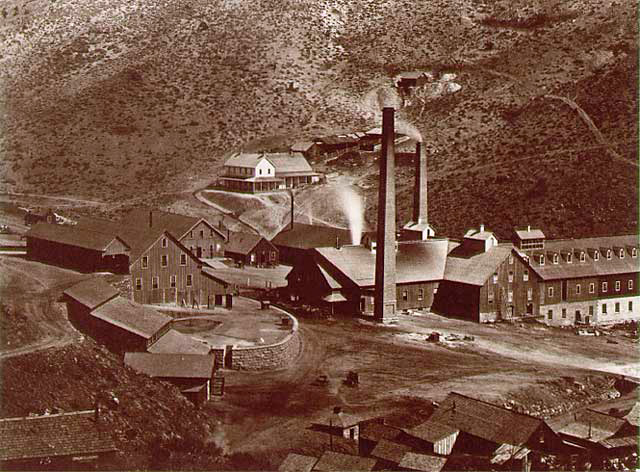

The early American landscape photographers fascinate me as one aspect of their work – recording ‘wilderness’ - has largely set the tone for the majority of landscape imagery produced today. Of course the full range of their work was much more varied than the ‘greatest hits’ that are typically reproduced. O’Sullivan, for instance, photographed mine workings as well as images of ‘wilderness’.

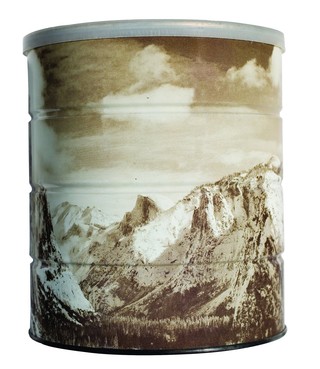

The mining images weren’t meant as criticisms of the despoiling of nature. He saw no irony in photographing both scenics and industry without ascribing precedence to either, perhaps because he didn’t feel our modern separation between nature and man. Even the great Ansel wasn’t above a bit of commercialism, one of his snowy images of Yosemite graced a tin of Hills Brothers Coffee. (However, Rockwell International’s posthumous and unauthorised use of “Clearing Winter Storm, Yosemite”, in an advert supporting tactical nuclear weapons, was considered a move too far by the Adams’ Publishing Rights Trust!)

Yet, the view that we have of these photographers’ work, edited by successive publishers and writers, would suggest an almost saintly relationship to the land. A passing knowledge may well lead to misapprehensions so it seems blindingly obvious to me that anyone who takes their craft seriously should try and understand its history, and ideally in the broadest sense possible by looking at many different kinds of photography. How else might we come to a fuller understanding of our own position?

Unfortunately, some recent conversations with photographers have led me to despair of what seems like a growing insularity. To be fair, I’m not sure that photographic insularity is anything new, or, more accurately, perhaps it’s always been a characteristic of those who are relatively new to the medium. However, I find one thing very worrying; the explosion of published photographs via the web hasn’t been accompanied by an explosion of articles on the history of our medium in the printed press. The photographic horizons of these nouveau photographers are bounded by Flickr, ePhotozine and the popular photographic press. It seems that for these individuals, very little happened in photography prior to the digital age. They might have heard of Henri Cartier-Bresson and Ansel Adams but it’s unlikely that they would know of Bill Brandt, Man Ray, László Moholy-Nagy or André Kertész.

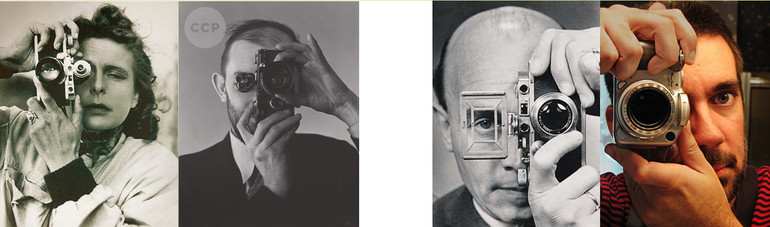

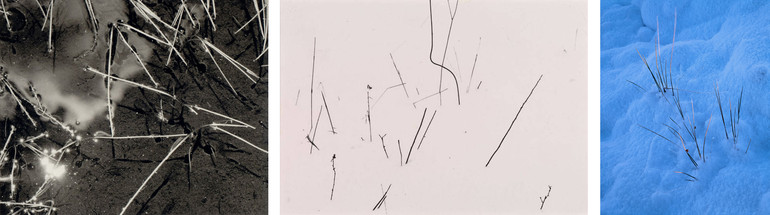

One up-and-coming photographic leader even asked who John Blakemore was and, depressingly for John, posed the additional question“…is he still alive?” Rather than art, these photographers are only looking to make ‘good’ photographs. And how is a ‘good’ photograph assessed? Why, just by looking at other recent photographers’ work - hence the endless repetition of ‘classic’ views and aesthetic points of view. Anything outside this milieu of ‘the recent’ is, seemingly, felt irrelevant. As they used to say in the 1960’s, if it ain’t ‘happening’ it’s nowhere. (That’s post-modernist irony, for any of you in doubt…) The photographic style that these innocents aspire to is, therefore, self-referential, with little regard for the wider landscape of ideas that is propagated throughout art. But we should always recognise that our current aesthetic sensibility didn’t arrive fully formed with digital technology. It’s the product of thousands of years of human development and tens of thousands if not hundreds of thousands of artists’ work and that history shouldn’t just be ignored. An attitude that only ‘now’ is relevant leads to people pointlessly reinventing the wheel - and mistakenly believing that what they’ve done is really neat and novel. Knowing the history, on the other hand, can lead to ‘knowing’ photographs such as this collection of self portraits.

Lest you misunderstand, I should make it clear that I’m not blaming the newbies for their paucity of understanding. In my mind, the blame lies squarely on the shoulders of commentators in the monthly photographic press – I know, I know, all the photographic information you ever need is out there on the web! But you have to realise what you’re missing before you can find it. What we need is some positive education. I feel that educating photographers about the history of the medium (and not just telling them about the latest whizzo gadgets) should be part of the magazines’ remit. However, in their frantic scramble to keep things current, they never seem to think to set today’s photography within a wider historical context. Whilst I can understand that there’s no financial imperative (understandably, the major imperative they’re interested in is keeping the advertisers happy) I don’t see any reason not to explore the history of the medium in the magazines. I’m not asking them to do it out of the goodness of their hearts either. Such an article strand could, if written and presented well, help to keep readers on board, something they’re all desperate to do in these difficult financial times. I’ve heard that many readers cancel their subscriptions at the end of the typical 24-month cycle of technical articles when they start to see topics repeated. But there’s no reason why the magazines should ever run out of material on the history of the medium. And, for all the reasons given above, there would be numerous benefits to photographers from looking back. Surely a win, win situation?

Might not camera clubs and societies also take a more active role in educating their members? Perhaps I’m doing them a disservice but it seems to me that they do very little to introduce their members to wider influences, beyond inviting a few guest speakers. In “Ansel Adams, New Light”, John Pultz writes about a visit by Ansel to a Detroit camera club in 1941 and the influence his workshop had on Harry Callahan, then just starting out in photography. During the camera club visit, Adams was fierce in his criticism of people’s work and technique - so much so that it apparently set some people’s confidence back years - but this was exactly the shock tactic that Callahan needed to realise his dream of becoming a photographer. Describing the prevailing cosy camera club ethos that had failed to galvanise Callahan, Pultz wrote,

‘Camera clubs called for personal expression in their rhetoric, but in practice they discouraged it. Their members won guaranteed pleasure and satisfaction by forswearing spontaneous personal expression for strict adherence to conventions and formulas, which would ensure success in print competitions and juried salons. Camera clubs and photography magazines encouraged amateurs to abandon simple snapshot photography for more carefully structured “pictures”’

Plus ça change… It seems to me that there’s still today a formulaic approach to making images for judging in competitions. Whilst it’s hard to pin down exactly what might characterise this approach I think that those are the pictures that surprise us and may make us exclaim, “How did he see that?!” eloquently proclaim the absence of a formula.

* * *

Perhaps there’s no appetite amongst club and society members for this kind of education but I can imagine something akin to a book reading circle where great photographic works are discussed and critiqued. At the very least the governing body for photographic societies should provide a list of books for background material. (I’d be really pleased to find out that they already do, so please tell me if I’m wrong in my assumption that they don’t!)

And we shouldn’t just limit our horizons to the history of photography. If we are serious about thinking of photography as an art – and we should be! – then we need to look at the wider worlds of painting, sculpture and music. For me, the most exciting find, by far, from my visit to Hay was a pristine copy of “Memory & Magic”, a retrospective look at the works of Andrew Wyeth. I’m a long time fan of Wyeth’s austere and emotive style of realist painting. His work is a million miles away from the abstracted landscape photographs that I love to make but this doesn’t stop me learning something from his work. No matter how spare his paintings, each leaves room for the viewer to weave a story from the slenderest of clues and cues. On one level they are simply descriptive, in the manner of a photograph, yet each is packed with emotion. Studying them to try and feel how he achieved this emotional charge is surely a lesson worth learning and applying to photography.

Painters seem to see art in a wider sense, but too often photographers see photography as a special category and one that need only refer to itself. Of course, it’s not the only medium that has this tendency, movies and television are also famous for their navel gazing. But that doesn’t make it right. The only way out of this solipsistic trap is to try and broaden our horizons. (I’m very aware that I’m probably preaching to the converted here, but please bear with me as I believe that we can never know too much.) Tim has already done a sterling job of bringing photographic books to your attention and introducing some of the great figures such as Stieglitz. But I think it would be great if we could start a library list of photographic and art titles to expand our horizons. I’d like you all to suggest books (send ideas to books@onlandscape.co.uk) and I think we could build up a really broad and interesting selection of recommended books that could become a useful resource for photographers of any ability. To start the ball rolling I’ve written down the books that I have found most important and interesting for me and my photography. We're splitting these into groups of four so next issue we'll have another four to suggest to you next issue, until then.

You can see more David Ward at Into the Light.

The beginning of a reading list

| Title | Author | isbn |

|---|---|---|

| A Concise History of Photography | Ian Jeffrey | 0-500-20187-0 |

| Another Way of Telling | John Berger | 978-0679737247 |

| Art and Illusion | EH Gombrich | 0-714-84208-7 |

| Beauty in Photography | Robert Adams | 0-89381-3680 |

| Beyond Order | Jan Tove | Out of print |

| Camera Lucida | Roland Barthes | 0-09-922541-7 |