Book reviews

Tim Parkin

Amateur Photographer who plays with big cameras and film when in between digital photographs.

In a previous article about books and photography David Ward challenged us to come up with some helpful titles. One such could be Georgia O’Keeffe and Ansel Adams: Natural Affinities, published in 2008 to coincide with an exhibition in the USA of the same name.

In a previous article about books and photography David Ward challenged us to come up with some helpful titles. One such could be Georgia O’Keeffe and Ansel Adams: Natural Affinities, published in 2008 to coincide with an exhibition in the USA of the same name.

Whilst there is an undoubted link between painting and photography, there are very few books combining landscape photography with landscape painting. Ansel Adams was enthused and inspired by photographers like Timothy O’Sullivan who had gone out into the American Wilderness to record their feelings for the landscape. Where Georgia O’Keeffe got her inspiration from is difficult to say. But she was married to Alfred Stieglitz who was primarily responsible for photography being accepted as an art form between the two world wars. Stieglitz helped launch both Adams and O’Keeffe in their respective careers, and his relationship with the two of them was complex, not to say crowded.

Most landscape photographers will be familiar with the work of Ansel Adams and probably own not just some of his monographs, but also biographies about him, such as those by Jonathan Spaulding or Anne Hammond. Photographers may not be so familiar with the work of Georgia O’Keeffe, except in the context of her life with Alfred Stieglitz. Whilst O’Keeffe is well known for her floral abstract paintings, she is less well known for her paintings of the wild and unforgiving landscape around Taos and Ghost Ranch in New Mexico. An area she visited every year, and then settled after Stieglitz’s death. So like Ansel, landscape was in her blood. Both had a deep affinity for the natural world and travelled together through the South West of America and into Yosemite in 1937 and 1938.

It was the harsh landscape of New Mexico which produced reactions in both painter and photographer. Red hot mountains, sunburnt forests and trees, deserts, weather patterns and adobe architecture were the subject matter. These are reflected well in the section of O’Keeffe’s work along with the sense of blistering heat. But not so well in Ansel’s section of photographs as many of the photographs come from the cooler and easier California. Some of the snow detail photographs look out of place. It would be fair to say that O’Keeffe’s strong colour paintings dominate Ansel’s black and white photographs. He admits that the South West belonged to O’Keeffe saying that “noone else has extracted such style and color, or has revealed the essential forms so beautifully…..” Of course Yosemite was Adams’ territory commenting that “there is no human element in the High Sierra – nothing like New Mexico”.

It was the harsh landscape of New Mexico which produced reactions in both painter and photographer. Red hot mountains, sunburnt forests and trees, deserts, weather patterns and adobe architecture were the subject matter. These are reflected well in the section of O’Keeffe’s work along with the sense of blistering heat. But not so well in Ansel’s section of photographs as many of the photographs come from the cooler and easier California. Some of the snow detail photographs look out of place. It would be fair to say that O’Keeffe’s strong colour paintings dominate Ansel’s black and white photographs. He admits that the South West belonged to O’Keeffe saying that “noone else has extracted such style and color, or has revealed the essential forms so beautifully…..” Of course Yosemite was Adams’ territory commenting that “there is no human element in the High Sierra – nothing like New Mexico”.

The essays by Richard Woodward and Barbara Lynes explain their character traits, and there are excellent descriptions of their different motivations for being in the South West. In the case of O’Keeffe it was to get away from the ‘arty’ scene in New York and experience an isolation in which she could devote herself to her art. For Adams, it was an opportunity to meet some of the avant-garde New Yorkers, such as Paul Strand who stayed with O’Keeffe on occasion. Indeed it was seeing Strand’s negatives that did it for Ansel – their impact on him made him become a photographer rather than a concert pianist. Sharp focus and minimum manipulation in the dark room were qualities that stood out in Strand’s negatives.

The essays by Richard Woodward and Barbara Lynes explain their character traits, and there are excellent descriptions of their different motivations for being in the South West. In the case of O’Keeffe it was to get away from the ‘arty’ scene in New York and experience an isolation in which she could devote herself to her art. For Adams, it was an opportunity to meet some of the avant-garde New Yorkers, such as Paul Strand who stayed with O’Keeffe on occasion. Indeed it was seeing Strand’s negatives that did it for Ansel – their impact on him made him become a photographer rather than a concert pianist. Sharp focus and minimum manipulation in the dark room were qualities that stood out in Strand’s negatives.

The best essay though is by Sandra Phillips as she actually makes a good comparison of the artwork of Adams and O’Keeffe, or at least says what the influence was on their work. We hear how Adams admits to being ‘stirred up’ by O’Keeffe in Yosemite ‘to see things for himself’.

Whilst many photographers have identified a painterly influence, O’Keeffe said that photography was an influence on her painting. This may not be surprising given her relationship with Alfred Stieglitz. One of her paintings, entitled In the Patio VIII consists of a stream of clouds which certainly suggest the idea of equivalents, as espoused by Stieglitz. Ansel’s High clouds at Golden Canyon in Death Valley also reveal the ‘equivalent’ influence.

The feeling I get from the book is that it is more about O’Keeffe and her elusive personality than Adams. More assessment of their approach to art and photography would be of greater interest, rather than how they dealt with their fame. Both had a deep awareness and sensitivity to the natural world. The book would have greater value if this aspect of their lives was explored in greater depth.

The feeling I get from the book is that it is more about O’Keeffe and her elusive personality than Adams. More assessment of their approach to art and photography would be of greater interest, rather than how they dealt with their fame. Both had a deep awareness and sensitivity to the natural world. The book would have greater value if this aspect of their lives was explored in greater depth.

However we do learn of Ansel’s other interests such as membership of the Sierra Club and the wilderness Society which tells us something about the man and how those aspects of his life drove his photography. We hear that he made over 13,000 prints from about 2,000 negatives of the 40,000 or so he made. He made 1300 prints in various sizes of Moonrise, Hernadez, New Mexico 1941. He was instrumental in establishing the Photography Department at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and at the California School of Fine Arts, latterly the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Adams as a personality comes across as more generous of his time with great importance attached to people he knows and loves. O’Keeffe on the other hand does not seem to rely on anyone – not even Stieglitz. She could devote her entire life to her art without distraction, unlike Adams who revelled in social interaction and his open house attitude.

Adams as a personality comes across as more generous of his time with great importance attached to people he knows and loves. O’Keeffe on the other hand does not seem to rely on anyone – not even Stieglitz. She could devote her entire life to her art without distraction, unlike Adams who revelled in social interaction and his open house attitude.

The difference in characters is summed up by O’Keeffe writing that “ When I got to New Mexico that was mine. As soon as I saw it that was my country.” Contrast that with Ansel’s arrival in New Mexico which is non possessive or proprietorial. He writes to Stieglitz: “ It is all very magical and beautiful here – a quality which cannot be described……the detail so precise and exquisite….”

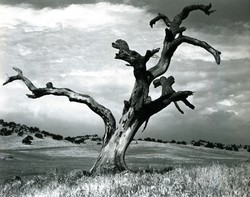

Comparing the photographs and paintings takes some work on the part of the reader. Examples are Saint Francis Church, Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico, painted and photographed in the same year, 1929. Ansel’s Dead Oak Tree above Snelling is similar to Gerald’s Tree painted by O’Keeffe. The quality of light and luminosity is there in both depictions, but they are pages apart.

The book itself is high quality – good paper and print and, well laid out with about 50 plates dedicated each to Georgia O’Keeffe and Ansel Adams. There are useful chronologies of events and detailed bibliographies for those who wish to research further. For anyone interested in the history and development of landscape photography as it relates to the work of one of the great painters in America, who was herself heavily influenced by photography, then this is a book to acquire.