Natural History Museum, London

Kevin Edge

Once a museum curator and then a cultural theory lecturer, he’s now a freelance writer on ecology and arts topics.

“Genesis is a journey to the landscapes, seascapes, animals and peoples that have so far escaped the long reach of today’s world” [extract from introductory panel].

April 11 – September 8 2013

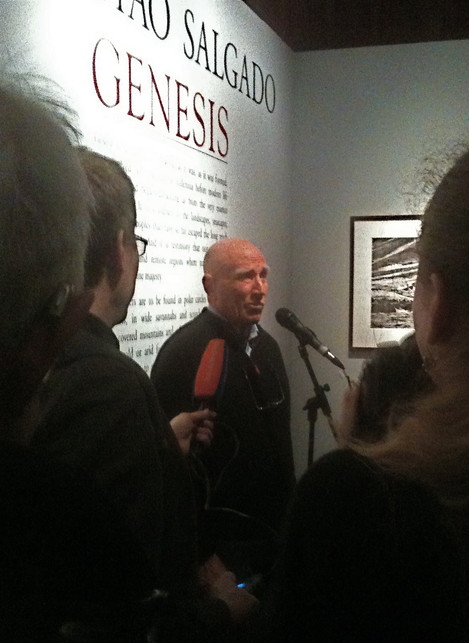

The early morning media preview of Sebastião Salgado’s new exhibition.

Genesis was well underway. Along with dozens of other critics and journalists, I had already enjoyed a welcoming hot coffee with pastries and was now marvelling at 200 stunning black and white prints on the gallery walls. Yet there was still one more pleasure to come: it was time for us to meet the person responsible for this eagerly awaited show. The photographer who had spent decades fixing his gaze on a hundred thousand subjects stepped forward and offered himself to the lenses of an international media pack.

Salgado stood with great poise before cameras and microphones and began to speak purposefully about this world premiere.

We quickly learned that Genesis – curated by his wife Lélia Wanick Salgado – was more than ‘just another’ portfolio on the wall and book in the shop. This impressive project symbolises his passionate desire to protect threatened landscapes, peoples and wildlife. In fact he spoke first, not of the photos but about the practical steps he and Lélia have taken since the 1990s to arrest environmental loss back in Brazil.

Salgado had grown-up on a Brazilian farm. Returning home after a long time travelling, he was shocked to see that the familiar trees and creatures of his youth were now either gone or under threat. With his help, native trees have been re-planted in a part of the Atlantic Forest, Brazil. With evident satisfaction and relief he said that two million new trees are growing and that the insects and caiman of his youth are returning to what is today a nature reserve.

So, what about the photography? with his camera, talent and newfound insight into rapid habitat change, Salgado set about what he called “an incredible trip into the Old Testament” where he would try and record portraits of that “45% of the planet which is still exactly as it was on the day of its genesis.” This documentary adventure began in 2004 and was of Biblical proportions, ranging across 32 countries and eight years. Salgado the idealist is, nevertheless realistic about human-led environmental change, explaining that his reforestation is really only a modest gesture and that today nothing on our planet is really ‘untouched’. Whilst using the conceit of pristine ‘creation’ he does not wish to make a fetish of a pre-human Eden or wilderness and knows people around the world cannot be asked to return to a primordial life. What he can (and does) do through Genesis is to show us all what a near-pristine planet looks like and asks that we pause and think.

At several points during his speech, Salgado the documentary photographer became more like a scientist and anthropologist, sharing lots of ecological statistics and human stories with us to drive home his environmental ‘call to arms’ alluded to in the show. Suddenly, aware that he may have eclipsed a photographer’s passive remit to simply bear witness, Salgado returned self-consciously to the microphone after his speech, reminding us all that really he’s ‘just a photographer’. But what a photographer he is.

The exhibition is divided into Sanctuaries, Planet South, Africa, Northern Spaces, and Amazonia & Pantanal. Landscapes appear in several of these sections and are either the central subject or a contextual backdrop. In one, an aerial shot captures snowfields in Siberia dotted with reindeer and their Nenet herders far below. In another, Utah’s Grand Canyon is cleverly re-imagined by Salgado. Standing above the gorge at the level of National forest, he has pointed his camera straight across the canyon brim from edge to edge; we know there’s a great gorge down there, we no longer need to peer into it. This shot is topped-off by drifts of cloud reminding us of the water cycle and erosion processes that first formed the canyon.

2. The Anavilhanas, the name given to around 350 forested islands in Brazil’s Rio Negro, form the world’s largest inland archipelago. Covering 1,000 square kilometres of Amazonia, they start 80 kilometres northwest of Manaus and stretch some 400 kilometres up the Rio Negro as far as Barcelos. Brazil, 2009. © Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / nbpictures

A large print of a volcanic landscape in Kamchatka, Russia at first confounds the eye. Here Salgado eschews a simple shot of monumental cones, and instead gives us a picture composed of wide, semi-abstract bands of rock, ash, tundra and cloud. The photo of sky, reflections and curling strips of land of The Anavilhanas, the world’s largest inland archipelago is beautiful to behold, whether seen from across the gallery or with your nose very close to the glass. How can the light, chemistry and paper of the photographic process do this? Salgado’s printers, Valérie Hue and Olivier Jamin need a name check!

Every picture appears perfect. Each avoids cliché, and even that well-worn subject: a group portrait of wild elephants excites the eye in Salgado’s hands. Each photo is strong in composition, texture and tone (achieved sometimes with a filter) but is never a cold abstraction or a formalist exercise. The graphic power of each flawless print on Ilford’s Galerie Prestige Gold Fibre Silk paper does play enticingly across the retina momentarily, but Salgado’s remarkable depth of field and focus always lay bare the subject matter.

Any criticisms? Well, some might feel that the show is too tightly hung, but I think the ‘press’ of a few busy walls adds a clamour and urgency to the project without ever really compromising individual pictures. [Illustration 3] One colleague remarked that the thematic layout was a bit confusing for him. For me, the minimal labelling across the show and the sheer aesthetic power of the prints is the right way to pull viewers around; the introductory and closing panels tell us all we need to know.

One minor concern for me was the way in which indigenous peoples were portrayed. Some photos (but not all) seem to stress the ‘sensation’ and surface texture of non-Western tribal ornament such as lip plates, or cheeks rubbed with the ash of cow dung. Was Salgado treating faces a little like rare and patterned landscapes in these cases? I raised this with another reviewer, but he thought all photo-portraits are, to some extent, objectifying. Some might see that in some photos people become what art history calls ‘staffage’: anonymous, secondary figures shown in a landscape picture for reasons of scale and general liveliness.

4. In the Upper Xingu region of Brazil’s Mato Grosso state, a group of waura fish in the Piulaga Lake near their village. The Upper Xingu Basin is home to an ethnically diverse population. Brazil, 2005. © Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / nbpictures

Given Salgado’s record and values, this last concern is more likely to be a case of him wanting to show the continuing but often precarious relationships of many humans with surroundings alien to the majority.

The Book of Genesis records how God created the world. Salgado is bearing witness to it for us all: shots in time for all time. Salgado told us: “We are right on the limit, we cannot cross this point, we must preserve…” We can only hope that enough people, be they in or out of power, get to see Genesis before rates of destruction and loss across the Earth accelerate further. One question that Genesis asks is whether we can each become motivated enough to do something? Revealing the world with a camera is good, maybe planting some more native saplings too in imitation of Salgado’s new forest would be even better.

Ed - There is a video of a talk that Salgado did on Vimeo that is quite interesting (although the audio is poor).

Click here to visit the Natural History Museum for more information and a short slideshow: