A Look at a Photographic Meme

Tim Parkin

Amateur Photographer who plays with big cameras and film when in between digital photographs.

To stand on a coastal cliff and look out over an expanse of sea and sky can be a humbling and sublime experience. The simple junction of water and air, sometimes clearly visible as a straight line and at other times smudged so that the difference is barely discernible, has a fascination that must have inspired people since the dawn of civilisation.

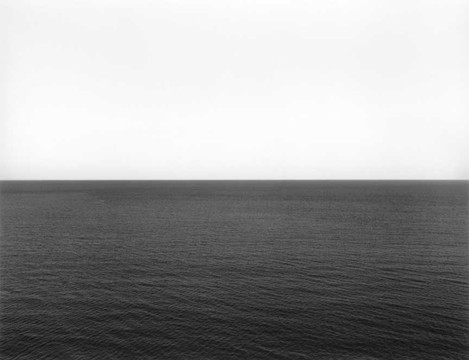

As photographers we are probably familiar with the work of Hiroshi Sugimoto whose minimalist, black and white seascapes seem to have provided the prototype for an entire genre of images, but you won’t be surprised to know he wasn’t the first person to have his muse tweaked by such subject matter. In fact, you have to go back to the early 19th century to find the roots of this minimalist horizon-centred aesthetic in mainstream art (if you know of anything earlier we’d love to hear about it!).

Much of landscape photography as we know it began with a solitary German painter, Caspar David Friedrich. His “Stimmungslandschaft” or literally “mood landscapes” approached nature as a subject in its own right and although his images often included a solitary figure or “Rückenfigur” (back figure), the subject is there to symbolise the viewer and to help prompt them to engage in the view as if they were there. Our visual lexicon of nature is now suitably rich that we instinctively view a scene as if we were there (given context of scale etc).

Friedrich’s first seascape that could be considered as the germ of the horizon idea is “The Monk by the Sea”: a truly revolutionary, minimalist landscape replete with white horses and reeling gulls and a presumably retreating storm on the horizon as night turns to day.

The sense of majesty in the image is profound, although many critics at the time didn’t ‘get’ it at all. “No moon, no storm, no sun, no thunder, no boat or ship, not even a sea monster” stated one, obviously wishing for bombastic Greek mythos. Friedrich took the idea even further into the abstract with his 'Sunrise at Sea' in 1828, which as an aesthetic seems very familiar to us today.

It was Turner who took the minimalist ideal a whole stage further though. In the late 1820s, he produced a series of near abstract views of sea and land or sky and land (sometimes it’s difficult to tell) that look so different from everything that had gone before that it appears to have arrived from a different culture.

A particular image of note is “Three Seascapes”, a study with apparently two different images until we realise that the dark area is actually another ‘land’ which shares a sky with one of the first ‘scapes. The result is akin to Rothko’s Multiforms, but born a century early. Other images such as ‘Seascapes with Storm Coming’, ‘Seascape with Bouy’ and ‘Study of Sea and Sky, Isle of Wight’ show Turner reveling in the sea/sky as an emotive concept rather than directly as a subject.

Even Constable and Whistler were making images of a similar sort, although it could be argued that these were more studies than final pieces, Constable’s in particular. Whistler’s seashore picture turns Courbet into a Rückenfigur.

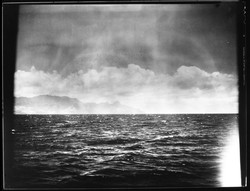

One of photography’s pioneers, Gustav Le Grey, created the first iconic ‘horizon’ photographs between the years of 1856 and 1857 with his ‘Solar Effect’ and ‘Seascape with Clouds’, amongst others. 'Solar Effect' is an example of Le Grey’s ‘theory of sacrifices’ where he suggested that detail and subject can be subservient to tonality, light and shadow - a portent of modernism perhaps.

A couple of years later, painter John Brett was looking from the other side of the channel with his “The British Channel as seen from Dorset”, a decade later Henry Moore with “Silver Sea” and at the turn of the century Edwin Hayes painted ‘Sunset at Sea from Harlyn’.

The 20th century begins with a surge of experimentation in the fine art world, arguably freed from the need to represent reality photography, and with that comes intense experimentation with shape, colour and form. Modernists such as Mondrian and De Stijl developed the style of neo-plasticism: the breaking down of form into blocks of colour and tone. Although the style doesn’t immediately have a link with the horizon based seascape we are discussing, it does represent art's fascination with the breaking down or deconstructing the subject into an elemental state and this fits well with the simplicity of a separation of sea and sky in a purely visual sense.

In 1946 Mark Rothko created his first Multiform paintings and these in many ways gave birth to a million simple abstractions. Any future photograph that divided the frame into two or more sections became ‘influenced by Rothko’ whether the artist had liked or even had heard of the artist. Rothko’s work was immensely powerful and influential though and it is no surprise that some in the art establishment saw it as a foundation on which to build.

I should add that of that period, I found only a Walker Evans image that fits this category well and could find little else. Photography in Europe, and in America to some extent, seems to have descended into a Pictorialist black hole prior to the first and second world wars. Art and particularly photography for that matter was seen as frivolous somehow and the it was only after the war the the pace began to pick up again. Artists began to experiment again and although the primary focus of photography seemed to be street and documentary work, during the 60s and 70s photography bloomed until the early 80s when the baby boom and the post war freedom had created a world of new artists.

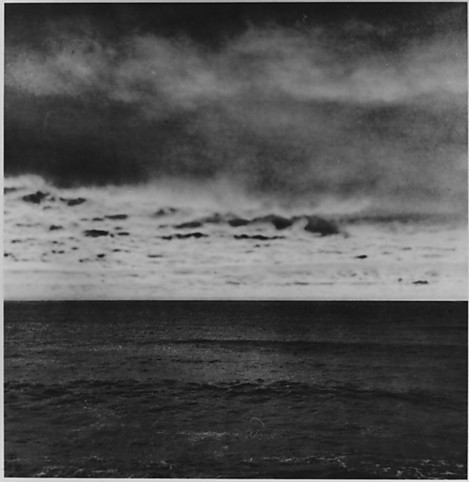

East German artist Gerhard Richter was a stand-out artist of the post war period (and now the top selling living artist). He created an astonishing range of works in painting and photography. A particular photograph from 1969 is pertinent here, “Seestück I” a homage to Le Grey in that he has stitched a sky to sea but in typical Richter style he has turned the clouds around to add a sense of dislocation. The Seestück series includes many oil on canvas works and could be seen as the definitive inspiration for the photographic style, especially as Richter used photography as a primary inspiration for his work (it would be great to see the original photographs for these paintings).

And here we finally reach Hiroshi Sugimoto. Born in 1948 and growing up during the post war period in Japan, Sugimoto has produced work in a variety of styles but it was upon seeing a Rothko exhibition in 1978 that he had the inspiration to produce his seascapes in almost direct homage to Rothko’s final black and white work that shortly preceded his suicide in 1970.

Sugimotos images, shot on an 8x10 large format camera, capture some of the depth of Rothko’s multiforms replacing the repeated layering of paint with the time-stretched exposure of waves and clouds. The series was taken all over the world, each repeating the overall concept of a central horizon line and no other detail apart from the waves and occasional band of cloud. On occasion the horizon line is banished completely by mist or rain.

Shortly after Sugimoto’s first works in 1980, Fabien Baron started an almost identical project. Rising early and shooting his 8x10 camera from various coastal locations, Baron built up a huge catalog of our now familiar half sea, half sky images. Whether Fabien saw Sugimoto’s images or not it’s difficult to say but my research suggests he started before Sugimoto exhibited his work. It wouldn’t be surprising if the two photographers developed the idea in parallel in some form of convergent evolution.

Since then we have had a variety of artists producing work with this abstract base idea including Richard Misrach’s wife, Debra Bloomfield; Gaylen Morgan and the wonderful work of Murray Fredericks, particularly his SALT project. Australian photographer Mike Stacey also sometimes works with this historic theme and we asked his for his thoughts and have included two of his works below.

The motivation that these artists have at depicting what seems to be nothing is what is interesting. Without wanting to sound too pretentious, the motivations are actually quite deep. There is some overlap between the various artistic statements that underpin each body of work, but each has its own slightly different intent. It would be interesting to know what that motivation was. What could possibly be so inspiring about pointing a camera into 'nothing'?

Each artist is looking beyond the landscape, beyond the world of things, at primal 'unseen' elements, transcending the usual view and verging on the spiritual. It is this looking past the landscape rather than at it, or into it, that provides the vehicle for the viewer to experience something more than what might be gleaned from viewing a traditional landscape image. Works such as these demand more from the viewer. Many folks will say: "there's nothing there", "what's there to look at?" Without the usual landscape props of trees, rocks or mountains, the viewer's eye is set adrift. This can be disconcerting to some but it is precisely this lack of reference that allows a deeper insight into the mind of the artist.

Mike Stacy

Just like Stieglitz’s equivalents, this form of abstract photography can work as a metaphor for many ideas whilst subtle variations in mood, colour and framing can evoke a range of emotions and memories.

The interesting thing about this theme is that many people could say that it has surely been mined so hard that there is little left. However the same could have been said in the 1960s and definitely in the 1990s after Sugimoto’s work. The development of the genre has proven that it isn’t the idea or theme that is the most important aspect of the works, it is how that theme is developed and the strength of the metaphors or philosophy on which it stands. Simple variations such as the point of capture (Fabien’s were typically from the beach, Sugimoto’s from an elevated perch), colour or black and white, fog or sunset, the inclusion or exclusion of rocks, boats, water texture, etc. Even the presentation of the work in terms of aspect ratio, print surface, framing; can all contribute to an identity that can support an infinity of conceptual ideas.

If anything the theme should act to break the shackles of history and allow the creative photographer to tackle anything they wish as the act of developing the idea will inevitably give it it’s own space.

Researching the history of this particular ‘meme’ has been a fascinating journey back through time and one that has made me taught me much about the communication of artistic ideas through the ages. I would highly recommend this sort of research as a way of discovering the history of a subject or visual topic but also as a way of finding out about the way ideas are communicated through the generations.

Finally - a big thanks to Neil from Beyond Words has kindly supplied the following bibliography to run alongside this article.

Bibliography

Rothko/Sugimoto - Sugimoto’s seascapes compared and contrasted with Rothko’s paintings

Hiroshi Sugimoto "Retrospective" - a full range of his work

Gustave Le Gray "1820-1884"

Gerhard Richter "Landscapes"

Fabien Baron "Liquid Light" - One reduced copy available from Beyond Words

Debra Bloomfield "Still" - Out of print but still fairly easily available.

Richard Misrach (Bloomfield’s husband’s) "Golden Gate" - might also be relevant here though Aperture now appear to be out of stock of the new edition

Boomoon "Naksan" - Similar work, website: http://www.boomoon.net/

"The Sea", ed Pierre Borhan - Good general sea work which is still available in hardback and paperback

Beyond Words can get any of these titles even if not listed on their website as long as they are in print.

And you’re in for a treat if you can find copies of these two out of print books: Waterproof (ISBN 9783908161264) and Sea Change (ISBN 9780938262329). If you can find Waterproof at a reasonable price, I’d be interested too!

![Swell Trails [Ether #17], Pacific Ocean, 2011 - Mike Stacey](https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/1110-810-1BW-OL1024px.jpg)