Part Two

Tim Parkin

Amateur Photographer who plays with big cameras and film when in between digital photographs.

David Ward

T-shirt winning landscape photographer, one time carpenter, full-time workshop leader and occasional author who does all his own decorating.

We're continuing with the second part of our interview with David Ward

Virgin River

T: This is an older picture.

D: Yeah. Quite an old picture really. Virgin river reflections. Probably the first reflection photograph or water flow photograph, that I was pleased with and I think it would have been 2000, or something like that. Quite a long time ago. First time I’d been to Zion. I was with Joe. We were leading a tour there. It was the last couple of days of the tour. We’d started off in Moab and gone to Arches and Canyonlands and Monument Valley and Page and Antelope and all of those places on route. And then ended up at Zion for the last couple of days. And it was the first time I’d seen these kind of conditions. So the colour is actually sunlight on a cottonwood tree, out of frame.

T: Was this Spring or ..?

D: Autumn. So it’s actually kind of a yellowy green. It’s just turning. So that’s where the reflected colour comes from. And it’s always intensified if the surface is in the shade. So this is in the shade and it’s lit by a blue sky overhead hence the blues in what would normally be neutral, in the white flowing water. I tried to go for a fairly short shutter speed. From memory, I think it’s half a second or a second, something like that because I wanted to retain the structure in the water. And I figured that if I made it too long, then I would lose that. It’s not really stopped down a huge amount. But it was quite easy to lay the plane of focus. The important thing to keep sharp in this, I suppose, would be the boulder. However, as I mentioned to you a little while ago, I’m not sure I’d shoot it now with the boulder. I think I would probably try and pick a portion of water more like the bottom half where you’ve got submerged boulders and flow rather than having the solid object as a punctuation mark.

T:The goal being to avoid having too strong a focal point? The classic meme in photography to say that’s my focal point, that’s the reason for the picture and everything else is just supporting factors?

D: Yeah. I mean I think in this picture that the real subject is the flow and the colour and I actually wonder whether the boulder, in a way, disrupts that - but I think many photographers get obsessed with the notion of a subject, that we are photographing a subject. And usually that subject is a solid object. And, unfortunately, quite often, it is "a boulder in the landscape".

T: Well, there’s a lot of them around.

D: There are a lot of them around. I mean, you go anywhere in the world, there will be a boulder, pretty much.

T: Or a tree.

D: Or a tree. Yeah. But actually, I don’t think the subject has to be something corporeal like that. I mean the subject can be 'flow'. The subject can be 'light'. And I think, increasingly, that I’m turning towards those as things to photograph.

T: Yeah. Like John Blakemore had 'wind'.

D: Did he? Yeah, I’d heard that. Poor chap. Yeah. Too many lentils probably. So, I think that I would look at something like this again, if I ever shot something like this again, in a different way. I mean I would still be fascinated by the colour and the contrast in the colour; the beautiful contrast between the blues and the almost metallic green, so it’s like a bluebottle kind of combination of colours. But I’m not sure that I would now shoot it with the boulder like that. Your eye ends up there. Partly it ends up there because the brightest part of the picture is actually on the boulder.

T: Yeah. Well, it’s got the contrast, hasn’t it? The bright and the dark together.

D: Yeah. And we end up at light. Basically we’ve evolved to look from dark to light, not from right to left, as some people believe... and if anybody tells you that you need to rearrange your photograph in order to read from right to left, they don’t know what the hell they’re talking about.

T: Otherwise, all these Chinese and Korean photographers wouldn’t be able to produce successful pictures.

D: Yeah. Well it’s, you know, we don’t read photographs like that. We don’t read photographs like we read a book. We read photographs in terms of trying to recognise the shapes. Basically, in evolutionary terms, we’re trying to see if there’s any threat. Whenever we look at an image, whether in person or whether we look at a photo, the way we’re programmed to look at a space is to look at the dark areas first, because that’s where the threat might be, and then to look at the light areas because that’s the least important bit, that’s the bit that you don’t worry about - because it would be bloody obvious if the Tyrannosaurus is standing in the light. I didn’t think about any of those things when I made the picture, but they do definitely affect how pictures are read. You know, one of the classic things that lots of printers do when they’re assessing whether an image is balanced or not, is that they take the black and white print out of the fix and they stick it upside down on the splashback and they look at it and go, “Yeah. That’s a bit light.” You can see it when you do that. And I think, because I was obsessed with the subject, at the time, I was probably at that, thinking, “Yeah. It’s brilliant cause your eye ends up on the boulder.” Now, that wouldn’t be where I want it to end up.

T: Yeah. You want your eye to move around more.

D: I think I would. I mean not randomly but for it to circle within the frame. I mean, I still like it, as a picture. I’m not saying it’s a bad picture. I’m just saying, we evolve, I suppose. At least, I hope I have and that I’m not still dragging my knuckles on the ground.

T: Somebody was saying this to me recently about how you should always print your pictures; try and get a final print of a picture quite quickly because, in another year or two’s time, you won’t like that picture in the same way or for the same reasons. So it’s almost like try and get it finished, get it out of the way in the way you intended.

D: otherwise you’ll do something different with it?

T: Yeah.

D: But if we evolve, is it wrong to do something different with it? Or just fall out of love with them. Yeah. I don’t know. Yeah. I certainly do fall out of love with pictures and I’m going to probably have a bit of a cull on my web site soon. Go through and remove some that I don’t like anymore.

T: What does a picture have to do for you to want to keep it for a long time, if you’re looking at your old pictures?

D: I suppose, just fundamentally, it needs to still hold interest in some way so there needs to be something about it that I still enjoy exploring visually. I don’t think there are any that I keep up for just sentimental reasons..

T: It was part of your development, maybe? The green slate picture for instance?

D: ..that’s on there but I do still like it. Other ones that were made round about the same period never made it to the web site. And I have also got a project ongoing to find all of the old copies of the walking books that I did and burn them! I cringe when I look at them. My Minor White period. Obviously it's a brine tank in a herring factory in Iceland. Now this was an interesting thing about a meme, I suppose, because at some point, I must have seen that picture by Minor White which is a quite famous black and white photograph of a similar sort of process, of some sort of thing leaching through concrete and leaving stains behind. In some ways, it's analogous to a Chinese painting. It looks like a set of waterfalls. So something probably triggered my reaction to this where I thought, yeah, that’s a picture I want to make. But I’d forgotten about it.

T: Yes. Purely subconsciously.

D: Yeah. It had disappeared into my subconscious. And then, it was sometime after it was published in Landscape Within that I revisited the Minor White book, "Mirrors, Messages, Manifestations" and lo and behold, there is that photograph. And I thought, damn! I gave a talk about a year ago at a camera club and I was recounting this story about how I’d felt quite kind of crestfallen over it cause whilst I still liked the photograph, it doesn’t feel quite as original as it had felt to me at the time. And I described how, in Minor’s picture, you had something that was analogous to the moon.

T: Yes. A little circle in the middle.

D: There was a disc, yeah, towards the top of the frame and slightly off to one side and I thought, I only had the waterfall and I didn’t have the moon as well.  And some guy piped up, “Yeah, but you got a cow in yours. He hasn’t got a cow in his.” And I’d never noticed that this set of shapes over on the right hand side of the frame looks like a cow, staring out of the picture. Look, there’s the horn and there’s the light catching the top of its head, there’s the tail. And the whole works. Yeah. So mine is better. I do have a highland cow in mine and he only had the moon!

And some guy piped up, “Yeah, but you got a cow in yours. He hasn’t got a cow in his.” And I’d never noticed that this set of shapes over on the right hand side of the frame looks like a cow, staring out of the picture. Look, there’s the horn and there’s the light catching the top of its head, there’s the tail. And the whole works. Yeah. So mine is better. I do have a highland cow in mine and he only had the moon!

T: Yeah. Moon or a cow. You pick which one you prefer.

D: Both would be better, wouldn’t it? "cow jumping over" would be absolutely the ideal, wouldn’t it?

T: Yeah...

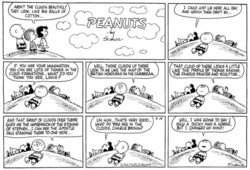

D: I do like the symbolism, I suppose, that arises from the picture though. The fact that you photograph one thing but it’s alluding to something else.  And that’s something that I’m interested in photographically. If I can find something that can stand in for something else, that suggests something else. And the classic thing that we all do which is that when you see faces in inanimate objects. It doesn’t matter what it is but you can see the outline of a face. There’s a brilliant cartoon – Schulz’s cartoon – and there’s Charlie Brown and Snoopy and I can’t remember which other one, Linus or something, lying on top of the hill and they’re staring up at the clouds and one turns to the other and says, “Oh look. That cloud over there gives me the impression of the Stoning of Stephen”. “And what do you see Charlie Brown?” And he says, “Well, I was going to say I see a ducky and a horsie but I’ve changed my mind now”. Yeah. We’re programmed to look for patterns is what it is, basically. We’re programmed to look for patterns and this guy was obviously programmed to look for cow patterns.

And that’s something that I’m interested in photographically. If I can find something that can stand in for something else, that suggests something else. And the classic thing that we all do which is that when you see faces in inanimate objects. It doesn’t matter what it is but you can see the outline of a face. There’s a brilliant cartoon – Schulz’s cartoon – and there’s Charlie Brown and Snoopy and I can’t remember which other one, Linus or something, lying on top of the hill and they’re staring up at the clouds and one turns to the other and says, “Oh look. That cloud over there gives me the impression of the Stoning of Stephen”. “And what do you see Charlie Brown?” And he says, “Well, I was going to say I see a ducky and a horsie but I’ve changed my mind now”. Yeah. We’re programmed to look for patterns is what it is, basically. We’re programmed to look for patterns and this guy was obviously programmed to look for cow patterns.

T: A farmer probably.

D: He probably was, yeah.

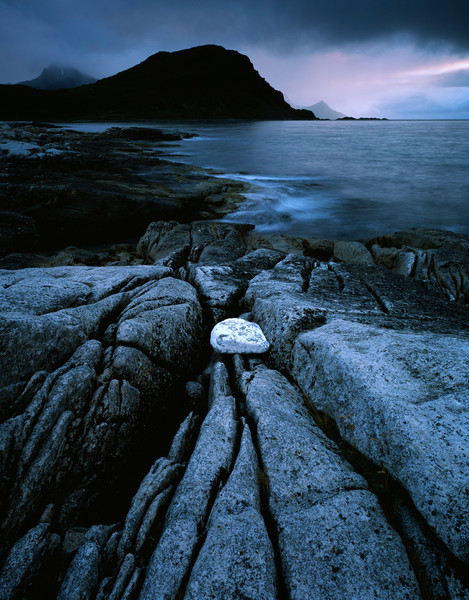

Vikspollen

D: Vikspollen in the Lofoten Islands. One of my favourite vistas I suppose because it’s moody, apart from anything else but also because I like the dynamic quality of the foreground with the leading lines, I suppose you would say, naturally eroded into the rock leading to a nexus, a point at which sits a rock covered in white lichen. And then the energy of the photograph seems to flow through and out into the wider landscape beyond. This is made on a workshop trip six years ago maybe now. And we’d had dinner at the hotel and people were saying, “Well, let’s go out for sunset. It looks hopeful.” And we went out and when we got out, the cloud all came in and everybody was kind of miserable because they weren’t going to get the operatic end to the day that they were expecting. And I got really excited about this spot cause I said, “I think this is fantastic. It’s a really good composition and I like the mood in the sky and you should all photograph - you should look at this and see if you can work out something to do.” And they all kind of, “No. It’s not what I want to do” and wandered off. And for me, that taught me a lesson, I suppose, which I probably already to some extent learned which is that lesson about being receptive and not going with just a notion that you’re going to do a particular thing because you become a prisoner to fortune if you do that.

T: It’s a game of roulette.

D: So you go there and you’re going to shoot that and, actually, when you get there, the light’s not what you wanted so people either shoot it because I’m here and they get a picture that doesn’t work very much, or they don’t shoot it and go home feeling miserable cause they’ve failed to achieve their goal.

T: The 'double zero' didn’t come up.

D: Yeah. Some people say that I placed that stone there. I’m going to completely refute that. I just moved 400 others out of the way. No, I didn’t place it there. It was entirely chance that it ended up there, presumably because it narrows so the waves had dragged the stones backwards and forwards and that one had ended up stuck in the kind of wedge at the bottom and it’s not a white stone. It is a lichen that’s growing on the stone that’s coloured it like that.

T: It’s obviously come up from further up the beach.

D: probably a big storm, big waves rolling in, it got pulled down the beach and then ended up stuck.

T: Now, you’ve used this compositional meme in other places. I’m not sure, consciously or subconsciously, of having an X, a vortex of some sort in pictures.

D: Yeah. I think, at first, unconsciously. And then, after I’d done it two or three times, I thought, “Oh God yeah. I’m doing that, aren’t I?” I kind of started to recognise it in my work. I don’t think I’ve done it for a while because I think as soon as I became aware of it, I kind of made a conscious decision not to do it. But I suppose one of the things that I liked about it was that it was breaking the rules in lots of ways. It’s more or less slap, bang in the middle of the frame, that white stone, which is where you should never place anything. Yeah.

T: No. Off to one side, darling.

D: Off to one side. It’s not a third of the way up or a third of the way down. The lines that lead you through go through the centre of the frame and they don’t go diagonally from edge to edge. They don’t do the things that you’re supposed to do.

T: It almost divides the picture into two, doesn’t it? As well, with the tones and the rock.

D: Yeah. It does, almost. It’s also the graduation that I used in order to hold the sky back that meant that that mountain in the background is darker than it would have appeared if you were stood there. But actually, I think that all adds to the mood that darkness is a signifier of mood as much as light is. And the way that the stone is very much the brightest thing in the whole frame, your eye ends up there and then travels out. But because it’s the brightest thing in the frame, your eye ends up there but then also your eye travels out again and turns. It’s interesting. You used the word vortex. It’s like it kind of sucks you back into the centre of the picture and then you swirl around and you get back out and you come back in again. So the leading lines kind of start you on a journey through but you always, it’s like an attractor..

T: Yeah. That’s a good word for it.

D: So I think in some senses it’s challenging as a composition but I also feel that it has a really good sense of mood. It’s quite sombre. There’s only a little hint of warmth in the colour of the sky. But I like that. I like the fact that it’s not full on sunset. The very thing that everybody else was looking for was not what I was looking for; perverse or what?

T: Presumably you’ll take some of those ideas that you’ve learnt from that one into other pictures in the future.

D: Yeah. I think so, yeah. I think for me, it was one of those seminal moments where you make a composition and because it feels right at the time, it’s very much an instinctive process for me. I don’t sit down and think, “Oh I need to do it like this.” It all felt right; positioning the camera kind of centrally on that axis from the grooves through to the block of the mountain in the background, and the white stone there, all felt absolutely right. And ..but actually, then, when you look at it afterwards, you realise there’s lots of other things going on that you haven’t, perhaps, noticed.

T: I was wondering that because when you talk a lot about pictures like this, and when anybody talks about pictures like this, there is the sort of misconception that people have when they are first coming into photography that you were thinking about that when you were taking the picture. I’ve tried to explain things to people by saying a lot of the conscious thinking gets done away from the camera, when you’re looking at pictures at home or you’re looking at other photographers or chatting about things, and then when you go out, that drives an unconscious process; some of those things you’ve thought about previously, get sprung now and again.

D: Yeah. I think, as much as possible, I try to compose using my subconscious mind as much as possible. In other words, it’s about feeling rather than about expressing in language.

T: Yeah. But you think some of that feeling gets fed from thoughts you’ve had when you’ve been away from the camera and looking at pictures and thinking about them?

D: Almost inevitably because I think that all of our problem solving comes from assimilating past experiences. I think one of the things that’s a myth which probably was generated by dear old Ansel, is this notion of visualisation, that the genius auteur, the incredibly talented photographer goes and he stands somewhere and he immediately knows exactly how the photograph is going to look and he works out in his head how it’s going to be printed and all of that stuff. And in my experience, that’s not how it works. My experience, you kind of wander along in a bit of a daze and stumble upon something so it’s about being in the receptive state. And Minor White said, “Being as receptive as an unexposed piece of film, pregnant with possibility upon which any image might be written.”

T: Oh he was an arty bugger, wasn’t he?

D: He was an arty bugger - But it is a good quote. It’s about being in what the psychologists would call, the flow state - a kind of meditation. And so it sounds really airy fairy and kind of difficult and "oh God, I could never do the meditation." But actually, probably every photographer has because it’s that experience when you kind of come to, having knelt in a puddle for half an hour and not noticed that you were doing it because you’ve been lost in the moment making an image.

T: And nothing else has been in your head at all.

D: Nothing else has mattered. So you might have been, at a conscious level, you might have been dealing with technicalities. You might have been dealing with metering or filtration or ‘Oh God, I’m going to put it on aperture mode or whatever else.’ But actually, most of you is lost in the subject cause most of you is lost in a place where time becomes elastic, where it stretches and thins and weird stuff goes on. And that is the ideal place to be in order to make a photograph. Now it doesn’t mean that you’re unaware of your surroundings. It’s a hyper-acuity. There’s a hyper-connection that goes on. And I think that’s one of the things that makes us incredibly tired when we’re really in photographing mode because we’re really looking. We’re trying to look as much as we possibly can and, for most of our lives, we don’t because there’s an overhead, there’s an energy cost to looking. Our brains have to work harder to look. Most of the time, we kind of do visual shorthand; We join the dots. So when you’re navigating somewhere, you join the dots. You don’t actually look at every single piece of pile in the carpet. You don’t look at everything around you. You don’t look at all of the detail of the stuff on either side as you walk between all the boxes, say, here in your office.

T: yes it is kind of untidy.

D: But you don’t study all of that detail when you navigate it.

T: No. My wife does that. She’s got hyper acuity for clutter!

D: Yeah. I’m not going to say anything. Sorry Charlotte! So there are reasons why we don’t normally kind of spend that much energy on seeing but there are huge dividends to be paid as a photographer or an artist. I mean you can’t buy spending that energy on seeing

Conwy

T: Now, a landscape landscape but not. Actually one of my favourite of your vistas. As we were mentioning earlier. It’s not really. It’s more about an abstract than it is a vista.

D: Yeah. It’s back in Landscape Within, I defined an intimate landscape as something which excludes the sky. And this does exclude the sky but it still describes a huge space. I’m looking across a valley. I think it was probably shot on the 210mm lens (55mm equivalent) so you’re probably look at a distance of maybe a mile or something to the distant trees. So it’s a big space. But the snow on the ground and the soft light have enabled the space to be kind of abstracted. So it becomes about form and it becomes about flow, rather than about description. Now that’s not to say that you can’t look at it and know that it’s trees and know that it’s a hillside and all the rest of it but the energy and the sense in the picture, I think, comes from a level of abstraction. And one of the things that I think attracted me to making the image like this was that the central band of trees,I always see it as running from left to right, even though I just told people you don’t do that. And then it curls back round on itself and it narrows down and then it kind of peters out. And then I think your eye kind of ends up at the group of trees at the top-left, and then you kind of fall back down into the picture. And there’s this kind of motion of your eye through the picture, which I think is quite satisfying.

T: Yeah. It’s like a dynamic balance of some sort.

D: Yeah.

T: But it’s the shape from the way you diffuse light. The shape of the snow and the shading on it that creates enough sense of three dimensionality in there to stop it being completely abstract.

D: Yeah. Well, and also, you can recognise them as trees although you can’t recognise their scale exactly. You know, are they 20 foot trees or 100 foot trees or those kind of things? There’s not enough information for you to ascertain that. But if you kind of screw your eyes up and look at it as a series of shapes then the structure, the skeleton of the image is all about that abstracted state. When I started out making images and making vistas, most of what I was trying to do was to make illustrative images; images that depicted a space in the clearest possible way. And I think this was an attempt to try and marry what I’d learnt from making the intimate landscapes to making more abstracted images and try and kind of join that with the notion of depicting a larger space. Now that sounds like I thought of all of that before I took the picture but I’m sure I didn’t.

T: How old is this?

D: It was on a Death Valley and Mono Lake tour. About 2004, 2005. So it’s quite old. Yeah. And it’s pretty much drive by shooting. It’s by the main interstate going from Mono north. I had to walk through thigh high snowdrifts to get to the point where I could take the picture but you could see it as you drove down the road. You could see this shape of a really beautiful valley.

T: And there’s a lovely separation between everything in it, as well.

D: Yeah.

T: Which is something easy to do when you’ve got something at your feet cause you can move around very quickly.

D: Yeah. But here I had to move up and down through the thigh deep snow in order to find the right spot to do that. But it’s also because of that soft light that you talked about. So not long after I took it, the sun poked out between the clouds and there were strong shadows coming from the left hand side of the frame. And they joined that band of trees through the centre, through to the kind of island of trees. And then the whole thing ceased to work. Also the top of the picture was in shade and so there was a shadow line at the top left hand side of the picture which also kind of made it not work as well. So it’s about that kind of fortuitous thing of everything coming together but I suppose it’s more about one recognising that those factors had come together.

T: Now, being as it’s a landscape orientation picture.

D: A rare landscape.

T: And all of your pictures are portrait orientation.

D: Sweeping generalisations are always good.

T: Did you typically go out with a 4x5 portrait orientation frame in your head..?

D: Yeah. A good friend, Chris Andrews and I used to joke about this thing that if you wanted to make a landscape image, you got one free on tour and then, after that, you had to fill in a permission sheet. And it had to be sent to the committee to see what you’ve been up to, to do it or not.

T: There are two reasons why I ask. One is, after being at the Landmark Exhibition at Somerset House I can only recall a couple of portrait orientation images out of more than a hundred.

D: So that’s a USP for me, then.

T: A unique selling point perhaps but is there something about the contemporary art market that only wants landscape orientation pictures and is there something different in the way it changes the balance of a picture and was yours a conscious choice?

D: I don’t think you start it off as a conscious choice. It might have become a preference. I think it started off, probably, when you’re making a kind of wider view. You’ve got a 90mm lens equivalent to 28mm or whatever on the 5x4 and because you can get from at your feet to the distance, sharp, with a lens like that, it’s a way of absolutely maximising the description of space.

T: A tendency to play with that foreground and background relationship

D: It tempts you to really kind of really depict the space in its most dynamic way, I suppose. And why I ended up making more of those than landscapes...

T: Because people like Muench worked in portrait orientation quite a lot but there definitely a dominance of landscape orientation images in fine art.

D: The theory that I’ve heard is that most people ascribe something that’s landscape shaped as being more analogous to human vision. It’s not really strictly true in that our field of view is a squashed ellipse and it’s not rectangular in any way at all. But generally speaking, we scan from side to side. There’s the classic thing of if you want to hide from somebody, you go up because nobody bothers to look up. I don’t know how true it is that they teach soldiers to do that but that’s the sort of thing.

T: We also tend to scan horizons so that is backed by evolution I would imagine.

D: And maybe, because I don’t include horizons it ceases to be an issue.

T: The orientation does change the way you read a picture though

D: I think one of the things that happens is that we are trained. We don’t read pictures from left to right but we are trained to hold our eye within a portrait shaped piece of paper by when we learn to read.

T: That’s quite interesting, isn’t it, that most pictures you see on walls are landscape and then everything would be media we look at...

D: ... is all upright. Yeah. And I have heard that, I can’t remember the reference, but I have heard it mentioned that you need to have a stronger composition in a landscape shape in order to hold people’s eye within the frame than you do in a portrait shape. There needs to be something compelling that leads people back in to the picture. So maybe in this instance, this little curl that comes back, is part of the reason why that worked. To be honest, the reason why I shot that landscape was because if I shot it upright, I would have got the bloody sky in there and I didn’t want sky in there. It fitted the subject in this case. Do I make the subject fit the frame, is probably going to be your next question?

T: Yeah. Well, when you’ve got an abstract subject at your feet, you do really have a choice.

D: You have much more ability to change things. Yeah, cause sometimes you can just change the orientation because there isn’t anything to tell anybody what’s up or down. So you can make it, represent it as a portrait when, actually, it wasn’t. Although I don’t think – have I ever done that?

T: Only when it works when you’re doing plainer subjects, doesn’t it? Cause I think even a hint of tilt can give things away

D: It would tell a lie, wouldn’t it? I don’t think I ever actually have done that. In fact, I’ve seen other people try and do it, in workshops, where they take something abstract and they say, “Well, I was thinking if I made this an upright.” And more often than not, you get enough clues about perspective to make it fail.

T: Yeah. It’s got to be flat, really, I think, to get away with it. But the other nice thing about mostly portraits or mostly landscape is it makes galleries on the internet a lot easier. They’ll fit in with each other. There’s a good reason! But then you would be better off shooting square then you never have to think about it at all

D: Do you think that’s why Mr Kenna did that, do you?

T: He didn’t have to make a choice then. In fact, I can put them all on the page

D: Yeah. That’s why we use square thumbnails, isn’t it? You don’t have to worry about arranging them

T: Don’t get on to me about square thumbnails or crops. It frustrates me, that does.

D: Does it?

T: Oh just the idea that somebody would have a picture that they’ve nicely composed and then show a thumbnail of it that’s been cropped without any sense...

D: something that a site like Facebook forces you to, don’t they, because they only have a square template for the picture that you show on your page. But at least they do allow you to reposition it so ...

T: You can get bigger versions too. But that’s just a pet beef.

D: Well the whole notion of thumbnail annoys me. So, I kind of would rather that people didn’t look at something at 100 pixels on a side actually….

T: What are they seeing?

D: it filters out a lot of subtle stuff, I feel. I don’t know, I think you were talking about Jem Southam and talking about how, in order to appreciate his work, you need to see the big prints.

T: I think so. I think there’s a scale element going on there. And pictures do change with scale, dramatically so. Beyond the web site cause I mean, you take a picture – like this, like the colony one here. You put that on a wall at 30 x 40. All of a sudden you’re looking at pictures within pictures. You put it on 100 pixels on a thumbnail, and all you’re seeing is a line with a couple of dots.

D: All it is is the graphic when it’s that small, yeah. I mean this one has a strong graphic but you can imagine a picture that is much more subtle, that has very little in the way of a graphic. In fact, ironically, I would guess that the one that we almost started with, with the boat shed, really small, would you see the grass?

T: No, you wouldn’t would you? You‘d see a red dot. I wonder if this is why we have a tendency to have a lot of simplicity in pictures these days is because people do click on thumbnails or other people are trying to. Some people are guided by their images popularity on places like Facebook of Flicker and if they’re pictures that are simply graphic, get a lot of feedback because people are clicking on them and them, maybe, adding a comment and the ones that aren’t graphic aren’t getting comments. They’re being herded down a certain direction of photography.

D: I think there is probably a filtering process that’s going on there but almost an evolutionary pressure I suppose, isn’t there? I mean, I like graphic images but I like the graphic to be combined with some level of subtlety as well, intrigue and mystery or something else going on rather than it being baldly descriptive. And I think that anything that has any sense of the mysterious has a big possibility of just passing people by because for some of those images you need to work at. Some of them you need to stare at for some time before it becomes apparent why somebody made the picture. And I think there is a huge kind of pressure for rapid consumption for people to consume the photography as fast as they can. And I think that that that’s not good for photography and it’s not good for photographers.

T: Difficult, isn’t it, because people are producing pictures at such a rate. And publishing them at a rate, as well. You try and keep up with a few colleagues or contacts on Flicker and you’re seeing huge amounts of pictures.... Going back to the size thing, has your appreciation for you pictures changed when you've seen them printed very large?

D: Yes it has. There was a picture I took of Mono Lake of some grasses and the back light. I’m not sure that I’m entirely happy, now, with the composition but I like what’s happening with the light. And when I saw that printed for the first time, at the last exhibition I had in London, as a 20 x 24, I was completely blown away with it because even though I’d stood there and made the picture, there was stuff that I hadn’t seen because there’s such enormous depth in it as a subject. You’re looking through the layers of grass and light shining through seed heads and stems and there’s an awful lot going on but when you stand there and look at it, you can’t apprehend that all in one go because, of course, you're having to refocus and scan. But when you make an image and you collapse of of that space and you make it all sit on a flat plane, you can suddenly interact with it in a completely different way than the way you could in reality. I mean, a different variation on that is something that many of those early American photographers were keen on; the notion of hyper-reality, describing things to an incredible degree.

T: It’s still very popular. People still use 10x8 and high end medium format backs, especially in the fine art market. They want engagement.

D: Yeah. And it is beguiling. And sometimes, it’s absolutely fantastic because it does give you access to a part of the visual realm that you would never reach without the camera as the tool.

T: You look at things you would never look at at the time - and perhaps couldn't even see. If it’s in a picture, you’ll look at it. If it wasn’t, if it was just there in front of you ...

D: That's the power of the photography, isn’t it? Because in a way, whenever you present a photograph, what you’re saying to a potential audience is saying, “Look at me. I’ve found this interesting.”

T: Yes. "This is significant"

D: Whatever level of significance it is. And obviously, that level of significance is, in some ways, coloured by the notoriety or fame of the artist. We were looking at that Salgado book last night. Sebastiao Salgado, fantastic photographer, and if he has an exhibition then I would suspect that his photographs of a subject would be more revered than similar quality photographs from somebody that nobody’s ever heard of. And that’s not actually kind of fair, really, because I’m sure there are an awful lot of photographers out there, maybe not in Salgado’s league, but there are an awful lot of photographers out there who are incredibly talented who are not going to get that attention …they’re not going to get people to actually invest the time trying to see significance.

T: No, well, I’ve just come back from helping to judge the wildlife photographer of the year. I was doing some of the technical judging for it and on my coffee breaks I was looking at some of Salgado’s pictures of animals. They wouldn’t stand a chance compared with the level of material I was looking at.

D: Hmm. Cause he’s not a wildlife photographer

T: are those pictures that strong intrinsically or are they just strong because it’s Salgado. Or are they strong because they fit in the project he worked on.

D: I don’t know. I don’t know. It’s a difficult one to call, isn’t it? And I’m going to return briefly to that notion of investment. When everything’s on the web, and it’s 100 pixel thumbnail, how much investment is required of the viewer? As opposed to when you had to go to an exhibition or you had to buy a book or you had to buy a print? Now, all of those things require at least a degree of effort and, in some cases, an outlay as well. And I think that that colours how we look at the pictures. Effectively, once everything is free, in a sense it becomes worthless.

T: I agree. Then it’s up to you to put value on it.

D: Yeah. ..and for some people, they’re going to be sensitive enough to invest emotionally or intelligently in the work and they will make the effort. But, for other people, because the means of dissemination, the web, is so facile, in the old sense of facile. It’s effortless. Then, I think that puts them off making an effort. They don’t need to. Why would you bother? Humans are fundamentally lazy, aren’t we?

T: Yes, and the choice of 'significance' can be influenced by how other people like something - social pressure

D: and the thing you were saying about how do you keep up is interesting, isn’t it? Because the output appears to have expanded enormously and I suppose there has been an expansion because we all carry a camera and a phone or whatever. But there’s also been an expansion in terms of it being available to other people because the images used to sit in a draw, or then once a year, Uncle Reg used to show you his holiday snaps on the slide projector.

T: Yes.

D: But there was never the abundance; there was never the ease with which you can access images as now. It would be interesting, and perhaps a very difficult thing, to work out. But has there actually been an increase in significant photographs or has this whole process, actually, meant that that’s impossible? So, if you look back through the history of photography and you look at the work of somebody like Ansel Adams or Edward Weston or André Kertész. These people stood out as beacons within their lifetime. Is it possible, now, for anybody to be in the same position that they were?

T: No. I don’t think it is, is it? Because they could only stand out because they had the background to be able to do so or they had the people who chose them. They don’t stand out because they’re the best. They stand out because the people who had the power, at the time, the critics or the museum curators or the mentors, patrons, had the money to throw at them; or had the position of influence to throw at them. And it’s not going to happen, now, is it? I imagine it must be very difficult for museums of contemporary photography to choose now. I was asking somebody about this recently, saying in the contemporary art world, how do you choose what’s a good photograph or how do you choose who’s a good photographer? And he was saying, it’s down to your course pedigree - tutors - and critics, mostly; critics and the curators of museums. But they make a decision on what they’ve seen in magazines or little journals or what shows people have put on themselves.

D: Right.

T: So it’s …

D: Yeah. But it’s certainly someone like Ansel relied upon the Newhalls to promote him. They were in a position in the East, based in Rochester, highly regarded as critics, and in a position to really kind of push him. It didn’t harm that he and Nancy were probably having an affair. And whereas Weston, whilst he was well known in his lifetime, was never as well-known as Ansel was because he didn’t have somebody who did that for him. He was much more the lone artist, keen on doing what he wanted to do and not, in a sense, I suppose, buying in to the whole process in the way that Ansel did. Now I wonder if some of that is to do with social background. Ansel was, effectively, upper middle class, as we would describe it. And Weston came from a much humbler background - although married into money. And I wonder if they just had different attitudes about how life was to be lived.

T: More than likely. You see people like Steiglitz who managed to get a huge amount of influence. I mean, whether you like his pictures or not, I know a lot of people who don’t think his photography is brilliant but he just must have positioned himself in the right place, pushing modernist art and becoming influential in photography.

D: Yeah. It was a tipping point where the… Malcolm Gladwell talked about Mavens; people who connect other people and I suppose Steiglitz was one of those. I don’t know that we’ll ever have a figure like any of those again. I don’t think Gursky’s the same.

T: No. I mean Gursky’s almost there, isn’t he? Because of the Bechers. They’re the ones that had the power and the connectivity because they had such a big reputation?

D: They’d already made the connections to the art world and the galleries and they're also running the course, which was highly regarded.

T: So you got all of their disciples would come out and made a big, big splash.

D: Yeah. Interestingly, when I went to the Polytechnic of Central London, as it was, and now University of Westminster, Victor Burgin was one of the tutors there and one of the top theorists of photography at the time. A guy called Simon Watling was there as well and he was also kind of quite high up in all that One of my classmates, a guy called David Bate, is now Head of Photography, I think, at Royal College of Art or one of those esteemed institutions. But I don’t think there was the same patronage that appears to have flowed with the Bechers.

T: Yeah. Well they just happened to be in the topographic exhibition.

D: They were an odd entry in it, all the pictures of the water towers and stuff? Right.

T: Yeah.

D: Oh right. I don’t remember them being there. That’s interesting. Right. Okay. So Szarkowski is the key. Szarkowski is probably the most influential.... We didn’t get off topic at all!

Boat

T: Interesting picture. I’ll remember you talking about this one so I know the story. But I’ll let you tell it cause you tell it so well.

D: It’s an upturned boat, a place called Achiltibuie, Wester Ross on the north-west coast of Scotland. It’s actually one of a pair of boats, sitting on a pebbly beach and I first photographed both boats. I was drawn to making an image because the palette was all very restrained. There were mostly kind of neutral greys, little bits of warm browns and beiges and just kind of punctuation marks of the copper nail heads. Very kind of restricted and all quite sympathetic. The two boats fitted together quite well within the frame. And in the process of making that first picture, I noticed that there was a tighter crop that I thought was more intriguing, which is the image that we’re now looking at. So, it’s a portion of the nearest boat and it's very abstracted. There’s a kind of sinuous curve of the – is that the transom at the back of a boat? I’m not sure –

T: I don’t know.

D: The stern.

T: The stern – "non pointy end".

D: The "non pointy end" of the boat, yeah. You can tell that both Tim and I are salty sea dogs – "Avast behind!". I thought that that kind of tightening up of the image and placing that curve in relation to the stones that were sitting on the bottom of the hull worked really well. So I made the picture and I was very pleased with it. I thought it worked. It makes it kind of intriguing because the space described is harder to understand. I thought it was a worthwhile picture - in fact it was on the cover of the hardback edition of Landscape Beyond. Sometime later - three years later? Something like that - I got an email from a chap who said, “Oh I see you photographed my stones. I put those stones on that boat.” and I kind of went into a slight panic about that because I thought, “God, so in a way it’s not my composition; somebody had arranged this.”

T: And they’d played such a strong part of the picture.

D: Yeah, I mean they’re an integral part of the composition, yeah. It’s almost like this curve is in orbit around them and the lines all point towards them and yeah. And I was really kind of upset by the whole thing. And then I thought about it for a while and I thought, “Well, actually, do you know, is it any different from erosion having placed something somewhere? Is it any different from weather having moved a cloud in to a particular point in the sky? Because it’s an unseen hand and it’s what I’ve done with the material to present it rather than what was done to the material in order for it to be in that position.

T: Yeah. And there’s a potential, it’s more prosaic if it was a fisherman who’d put them there.

D: Which is what I assumed: I assumed that somebody had piled stones on to stop them blowing away because they weren’t in a good state. In fact, they’ve now completely turned to matchwood. They’re not there at all anymore so…

T: So it wasn’t you taking out your anger?

D: No. it wasn’t no. No. No. No. It wasn’t me destroying the subject afterwards so nobody else could photograph it. No. So… although apparently, that has allegedly been done. But we won’t go there. So, I recovered, I suppose, you’d say, from that. And I’m still pleased with the picture because I do like the kind of incongruity of the space. It looks planar but it’s not planar. And part of that comes from using the movements on the camera in order to make sure that it’s as sharp as it possibly could be.

T: So there are no focus cues.

D: Yes. So it all looks like it’s on a single plane when, in fact, it’s not. It’s on contradictory planes. And that presented me with enormous headaches because the plane of focus is still a plane of focus, no matter what angle you lay it into your field of view.

T: Tilt is not magic.

D: No. You don't have bendy lenses so you can't make it fit that ogive curve. So you have to try and work a best fit for it. And, in fact, the very top left hand corner is slightly out of focus…

T: Yeah. Cause you’ve had to keep the rocks in.

D: Yeah. So that’s the kind of story of that one. Yeah.

T: It does say something about ownership. Cause like you say, if it had been a fisherman, it would still have been a conscious hand that put it there. But not purely for aesthetics. Or even if the fisherman put them there for aesthetic reasons, it would have had a different connotation. But like you say, does it really matter if it’s the image.

D: I’m not sure it does matter. I mean there’s this …the whole debate that keeps resurfacing about truth. Could you say that this is, in some sense, disingenuous because nature didn’t place the stones there; because a wave didn’t place the stones there, and I actually think, as Giles commented recently on a picture of mine, that photographers have as much right to the still life as a painter does.

T: Yeah. They can create things.

D: Yeah. And you could argue that somebody like Andy Goldsworthy, who’s described as a sculptor, is as much a photographer as he is a sculptor.

T: Yes. It’s interesting that he distanced himself from photography, didn’t he? So …consciously.

D: He did. Yeah, he did. I read an interview with him where he said that, “Well, I can’t be too good a photographer because then, actually, if people classed me as a photographer then that would, in some sense, devalue what I do.

T: Sad, isn’t it?

D: I think so, really, yeah. So he’s .. artfully artless, probably, in the way that he makes his images. So he doesn’t want to make them too good.