Lost Villages

Tim Parkin

Tim Parkin is a British landscape photographer, writer, and editor best known as the co-founder of On Landscape magazine, where he explores the art and practice of photographing the natural world. His work is thoughtful and carefully crafted, often focusing on subtle details and quiet moments in the landscape rather than dramatic vistas. Alongside his photography and writing, he co-founded the Natural Landscape Photography Awards, serves as a judge for other international competitions. Through all these projects, Parkin has become a respected and influential voice in contemporary landscape photography.

We are currently on the move to the East Riding of Yorkshire and naturally, any photography projects about the area drew some interest and in particular, it was Neil's Lost Villages project that really struck a chord when I was visiting the coastline of this area of the world. We caught up with Neil in the Summer for a chat about this and other projects. It's well worth including the project statement before continuing with the interview.

The Holderness coast located in the North East of England endures the highest rate of coastal erosion in Europe. The devastating consequence of this is villages and land slowly disappearing into the sea. The Lost Villages project aims to explore the constant battle between the North Sea and the mainland and to document the irreversible change taking place on the Holderness coast.

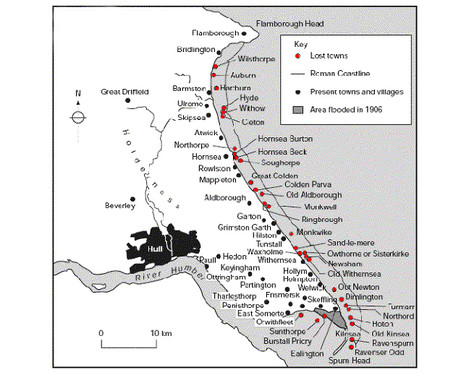

The speed of erosion has increased significantly in the past decade thanks to rising sea levels, which is linked, of course to climate change. It is estimated that up to 32 villages dating back to Roman times have already been lost to the sea. During World War II many outposts were built on this 61 km stretch of coastline. What remains of these outposts is now falling into the sea.

The historical events which took place on this coastline are fascinating. Since Roman times it is estimated that a strip of land three and a half miles wide has been washed into the North Sea. Two miles are estimated to have been lost since the Norman invasion in 1066 AD. Most of the information about the lost villages and towns of the Holderness coast are chronicled in the works of Abbot Burton (1393-99 AD) of Meaux Abbey, East Yorkshire. In the Chronica Monasterii de Melsa, he names all the towns and villages that have been lost to the sea.

One such lost village, Ravenser Odd, is particularly significant. Described as a mediaeval “new town” founded in 1235, it was also a thriving sea port. At the height of its fortunes in the early 14th century, Ravenser Odd was a town of national importance, regularly supplying the king with two fully equipped ships and armed men for his war with the Scots. It had a Royal Charter, a market and annual fair, a town mayor, customs officer and other officials, as well as numerous cargo ships, fishing boats and warehouses. There was also a court, prison and chapel. Shakespeare’s Richard II also speaks of a town called Ravenspurg (Ravenser).

By 1346 it was recorded that two thirds of the town and its buildings had been lost to the sea due to erosion. In the years that followed from about 1349 to 1360, the sea had completely destroyed Ravensor Odd. The final days were characterised by looting and general panic as the inhabitants took flight – many to neighbouring Kingston Upon Hull to start a new life – and latterly, the grim sight of bodies being washed up on the shore and mass graves. For a short time it became an island and a lair for pirates, before the town completely disappeared in around1366. It is the history of this particular village that has been an important inspiration for this project.

Today the village experiencing the severest threat is Skipsea. With a population of around 600, many homes there are set to disappear completely in the next five years. The average annual rate of erosion is around two metres of land per year, or two million tonnes of material. Most of the land here is covered by glacial till, a soft boulder clay deposited over 18,000 years ago. The clay material once washed out to sea is not entirely lost though, some of it being re-deposited on the Lincolnshire coast and some forming the Spurn Peninsula.

I have always been fascinated by changing natural environments. What drew me to this coastal area though is not just its reputation as one of the fastest eroding coastlines in Europe, but also because it is very close to where I grew up. When I was a child my parents would take me on day trips to this area, in particular a town called Withersea. Returning to this stretch of coastline as an adult after so many years and helped bring back fond memories of playing on the beach, my grandparents close by keeping an eye on me from their deck chairs.

The Lost Villages project will continue to document the erosion of the Holderness coastline and the difficulties experienced by the people, who are quite literally living on the edge there. In just over a year of working on this project, I have seen the coastline change markedly right before my eyes. This really does bring the speed of the erosion into reality.

Neil White

Tim: Hello Neil!

Neil: Hi Tim

Tim: How are things? I presume from your number that you're in London?

Neil: Very well thanks and yes I'm originally from the North of England but I've been living in London for about twelve years now I think.

Tim: Whereabouts are you from then?

Neil: I'm from a small village near Hull called Elloughton-cum-Brough. I left there a long time ago now though.

Tim: Could you tell me a little bit about your background as a photographer?

Neil: Yes, I've been a professional photographer for over ten years now and I've done commercial work for corporations and charities and some press work. I don't do much of that sort of work anymore, my work is more fine art and landscape I suppose. In 2006 I did an MA in documentary photojournalism at the LCC (London College of Communication) with Paul Lowe and spent a year trying to find other ways to take my photography and ever since then I've been moving towards different areas of photography. I've been using large format for this work almost exclusively. So I have two websites now, one website for my commercial and one for my 'proper' photography if you like.

Tim: So how did you get into photography in the first place - was that an original passion of yours?

Neil: Going back to 1997 I was travelling around the world and working overseas for about 18 months and I just bought an SLR camera and started to use it. It was a hobby for quite a few years and it just developed from there as I taught myself how to use it.

Tim: And the connection with the landscape?

Neil: I think really it was already there but it took me a long time to find it. It's only the last three or four years that I feel I've found what my photography work is about, to be honest. It's like finding your voice - I've been through lots of different areas to get to where I am but I've always been interested in landscape and nature but it's something that's come into focus.

Tim: Did the LCC course help you find this?

Neil: Yes it did help, my work was always about environmental issues, people working with land etc. But it's only really in the last three or four years this has become obvious to me.

Tim: What convinced you to do an MA? From commercial photography to an MA is quite a jump

Neil: Yes it is. It took me quite a long time to consider the decision really but it just seemed like something I needed to do. I needed more input from other photographers to grow creatively and open my mind to other things in photography and to educate me some more. And it really did open a lot of doors for me, and I don't mean commercially, I mean creative ones. It has been good for my career as well though.

Tim: What do you think you most benefited from the course? Was it your colleagues? Lecturers, or the course itself?

Neil: It was a mixture of things really. A lot of it was from the people on the course who I'm still friends with and I learnt a lot from other colleagues on the course - shooting different formats for instance. I was a documentary photojournalist style photographer shooting 35mm. But Adam and Ollie, two conceptual photographers, influenced me quite a lot. It's strange that when I did the MA I didn't really like art photography but the MA educated me more and I met some of the people who were doing this sort of work. On top of that, we had trips with other photographers for instance Tim Hetherington visited and was a big influence and met him quite a few times. He's still an influence but obviously, he's not around anymore.

Tim: So what project did you do during your LCC course? Was it one of the projects you have on your website?

Neil: Yes it is it's called Sami about Sami reindeer herders in Finland so I went to Lapland in North Finland for about five weeks and lived with Sami Reindeer herders and did a documentary project about their lives and also around an issue to do with logging which is currently affecting them.

Tim: Was this shot on digital?

Neil: It's kind of a mix of 6x6 Hasselblad work and also some 35mm. I kind of wish if I'd done it now I would have done it all on large format but that was 2006... I like the work, I think it's OK. In a way I was always thinking of going back to this - it wasn't really a finished project but things happen and money and time etc. You move on as well I suppose.

Tim: The picture of the hut in the middle of the series isn't where you lived during your stay was it?

Neil: Oh no definitely not. That was with some herders in a very remote area and it's where some guys live in the summer.

Tim: When you left the MA, how did you manage to balance up your artistic work and your commercial work because there is a different revenue model to say the least.

Neil: Yes. it's quite challenging really. The only reason I do the commercial stuff is to fund the artistic work now. I would have loved to have moved away from the commercial work and focussed on my own work but you have to make ends meet.

Tim: How long do you get to spend on project work then?

Neil: It's quite hard to say, it can fluctuate really. I try and split it 50:50 if I can but sometimes that's difficult. I also teach photography which I've been doing just over two years now for a few different colleges in London but I've also been trying to set up something myself. So it's another thread.

Tim: Could you talk us through a couple of the projects you've done since the LCC?

Neil: Yeah. The main project was obviously Lost Villages and is the first work I've shot seriously on large format and it's something I'm really happy with. It's done relatively well for me and I'm still working to get it out into the world.

Tim: Well it's a continually changing subject matter, isn't it.

Neil: It really is. I was working on the project for about 18 months and every time I went back the landscape had changed quite a lot, the erosion is that quick. Also, the project has an environmental link with erosion but I've got a personal connection with the area as it's where I visited often as a child. That was an interesting link and change from seeing the landscape as an adult after having those memories as a child.

Tim: In terms of interpreting the landscape and approaching a project such as this - how do you go about planning a project like this. Does it come fully formed as an idea or is it something that developed over time?

Neil: Well initially I just started going to take a few photographs and a lot more planning came into it over time. I'd start to do the occasional recce and find things I need to photograph and also plan what light or tides I needed. Sometimes I needed rare tides associated with the light so there was some luck and a lot of planning. I did various small trips over a weekend or staying or camping for a few nights and if I didn't get what I wanted I would just make notes about where I needed to be next time. I did re-shoot things quite a lot too. I had the luxury that my parents live quite close so it wasn't too challenging.

Tim: How do you know when a project like that is finished?

Neil: That's a very good question actually. In a way I see it as only stage one has finished. It's very difficult. Sometimes you have to say that this has to be put to bed and you need to move onto something else. With this project it warrants me going back even if I haven't done anything on it for a year or so. Also, I'm looking at doing some interiors of the houses that won't be there for very much longer which will give the project a different angle.

Tim: Are the houses destroyed before they fall over the edge of the cliff?

Neil: From the research, I've done the council and the people who live there are responsible for the demolition of the house before it falls over the cliff.

Tim: So you don't tend to get houses falling over the edge anymore?

Neil: No. It's happened in the past and there are a lot of World War II remains that have fallen into the sea.

Tim: You have one WWII structure in one of your pictures.

Neil: Yes there is a set of three pictures of them, I like the way they look like sculptures.

Tim: In terms of composition, there is quite a difference between the way that the sublime, epic landscape photographers approach it where the compositional forms are very obvious and strong and the way the contemporary photographs approach composition where it's almost a dirty habit. Your pictures sit somewhere in between in that they have a strong compositional balance but it's isn't "in your face" if you know what I mean. Is your approach to composition a continuation of your commercial work or did you bring anything from your MA course to it? (sorry for the long question!)

Neil: No problem! I think for me composition is one of the most interesting and important parts of photography. I seemed to have a natural sense of composition when I started shooting 35mm but I learned quite a lot on the MA from Paul Lowe and I got a lot of inspiration from fine art paintings like Turner or from cinematography. I don't know how I compose, I don't study it like that, but I do spend quite a time with the large format camera setting up a picture in terms of balance and placement of shapes.

Tim: It's interesting that you mention taking inspiration from painting as the approaches to composition in photography and painting tend to be quite different. When I started looking at composition in painting it was a surprise to see that they would purposely cut things off at the edge of the frame and do some strange awkward things with framing that photographers instinctively shy from and it's nice to balance the two approaches as most photographers seem to only look at other photography.

Neil: Yes I completely agree. More than ever I try to look outside of photography because it seems to have more interest. There are some amazing photographers out there but I also think there is a substantial amount of photography that isn't that great.

Tim: Who do you get inspiration from would you say.

Neil: One photographer that I really like but I always seem to get his name wrong somehow is Nadav Kander who did the Yangtze River work. For this project, his work was definitely inspirational to me. People like Alex Soth, Adam and Ollie Broomberg, etc. Take a look at my blog for more examples.

Tim: Who do you draw inspiration from in terms of painting.

Neil: For this project, I wouldn't say they really inspired me but Turner and Constable are the natural landscape artists that I look at. At the moment I'm quite into Chinese landscape paintings, not sure if it relates to my photography in any way but it's something I love looking at.

Tim: There is something about Chinese painting that seems quite photographic in look. It's very graphic and is strong in composition.

Neil: Yes it's really quite modern in look and I love the textures, the colours.

Tim: In terms of the project reaching completion, is there a goal to publish a book or exhibition.

Neil: It's been published in the Guardian magazine, not a huge spread but in the Saturday magazine. It was in Geographical magazine and I've had it on a lot of photography websites this year which is great for exposure but doesn't make any money unfortunately. One of the pictures of the road falling into the sea with the dog, that's done quite well actually - it's been published a few times.

[see here for a nice article including a description of taking this picture]

Tim: Are you looking at a book possibly.

Neil: Before that really I'd like an exhibition and I'm trying to find the time to raise some funds for that and then possibly a book a bit further down the line when there's some more work. But the exhibition somewhere up North would be a real goal.

Tim: What about the other projects that you have on at the moment.

Neil: I haven't really timed things particularly well. Last year I spent six months in Asia and I got back at Christmas time just gone. I've been working on a new project that I'm pulling together at the moment, it's taken me a long time to get together. I went into Nepal in the Himalayas and Ladakh in India and did a landscape project about glacier lakes and climate change. It's quite different to the Lost Villages project and I wanted to do something that showed I was moving on a bit. It's not out in the world at all as I'm still doing the artist statement for it but to have it ready in September/October would be the deadline.

Tim: What is the context behind it?

Neil: It's about glacier lakes which are trapped lakes behind glaciers forming very quickly and becoming unstable. The water is trapped by a moraine dam but these could burst and cause huge tsunamis could cause huge amounts of damage.

Tim: They sound fascinating - it's interesting because I saw a programme about these lakes recently and the damage they can cause when they collapse. The US Scablands is one of the biggest examples. There some scouring at the bottom of the English Channel that suggests it happened there once too. (Wikipedia page on Glacial Lake Outburst Floods for more information)

Neil: I'm trying to get the artist statement to give a take on my personal reasons for doing it. It took me a lot of planning and finances to do this and it was hard work. I've been to the Himalayas before but it was hard work and hazardous to do. I was out there in total for nearly six months, about two and a half months in Nepal. I had quite a few organisations who were helping with scientists giving information behind it.

Tim: So this is a collaborative project with a funding body?

Neil: Not really no. I just found contacts who could give me the information and support in order to guide it.

Tim: Well we'd love to cover it once it's ready. So is this new project taking up all of your time at the moment.

Neil: Yes, I'm still working on Lost Villages in terms of getting the exhibition sorted but the new project is taking priority.

Tim: Have you any prospective venues for exhibitions?

Neil: Not as yet - I'm talking to a few provisionally.

Tim: So your other projects - "It's Rubbish" and "The Wildlings". When were they done?

Neil: The Wildlings was done in 2011/2012 and was about ancient woodlands under threat in England. It's about the general threat of various commercial interests to woodland. It's not a completed project as I had to put it to one side - too many things happening at once. This was shot on medium format mostly but as I came to the end I worked on large format some more.

Tim: Why do you shoot on a large format?

Neil: The slower process definitely suits me much more as a photographer too. I never knew the format would work for me as it does but it just suits the way I want to approach things. You spend a lot more time taking individual pictures and I like that. The quality is amazing though. I can see it being a part of my photography for a long time. A friend of mine Kurt Tong who is quite a successful photographer was using large format whilst I was doing the MA and I thought "That's a bit beyond me that is" but obviously it stuck with me and when I started looking at fine art landscape photographers I thought that this is something I had to try.

Tim: There are still a lot of people using the large format in the fine art world.

Neil: I like to try different things all the time though so maybe I'll move on to something else later on.

Tim: If I asked you if you had a hobby would you say that your fine artwork is that hobby?

Neil: Yes it is definitely - It's what I want to do and as much as I want to have success with it the reason for doing it is because it's something I wanted to do. I've had some success with it to a point but the love of the work has to come first.

Tim: You mentioned a possible teaching project that you're thinking of developing?

Neil: Yes, I spent quite a bit of time in the projects in Ladakh and I fell in love with the place and the people, culture, landscapes. I'm trying to set up running workshops there. It's a very small season from June to September so I'm hoping to involve the community with these workshops not just to be an outside coming in and taking advantage. I'm also trying to do some workshops in London in Hampstead Heath. I live in Hackney in London and there are quite a lot of green spaces around like Hackney Marshes so I'm hoping to run some workshops there. All this will be on my website hopefully!

Tim: What sort of market are you looking at?

Neil: The first will be fairly basic courses teaching people how to use the camera but I'm more interested in the creative side so when I teach other courses I try and help people develop their interests and project work.

Tim: There aren't many people doing workshops on the contemporary approach to photograph or the conceptual side. Could be a fairly unique take.

Going back to the Lost Villages again, have you looked into the history of the area? I notice there is a map showing how the coastline has receded.

Neil: I've done a lot of research about the history of the area with regards to the coastline. That again was something that developed really. Beyond the idea to document the landscape I found a lot more interesting information about the area. There used to be a town called Ravenser Odd that became a sort of inspiration for the project.

Tim: We'll look forward to seeing the exhibition when it's all organised.

Neil: Thanks. It's been good talking to you.

You can see more of Neil's work on his project website and his commercial website.