An Alternative Viewpoint

Any photographer who chooses to make autumn their subject faces the significant problem of distinguishing their work from the heavy weight of photographic precedent. With so many images of autumn produced each year it is perhaps inevitable that a strong element of cliché cloaks the whole area. Is it possible to make work which lifts autumn into mystery and strangeness, enabling us to look again at the season with fresh eyes?

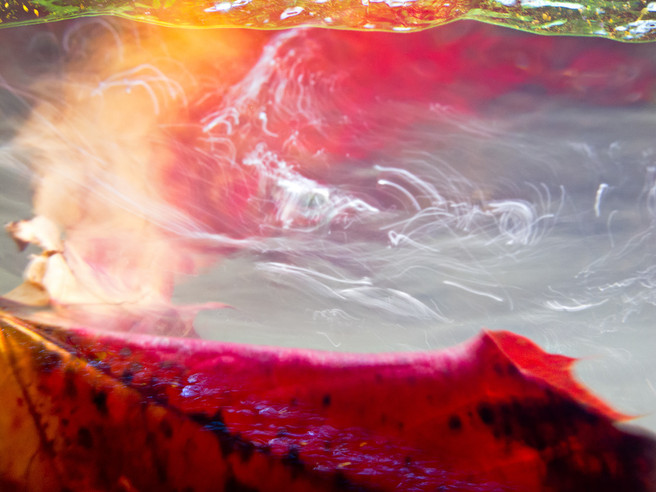

In the autumn of 2012 I made a series of images with some of the millions of decaying leaves that fall into the River Frome, in the southwest of England, and are carried, like brightly coloured jewels, along its length every year. Looking back at my notes that accompanied the research for the project, it is clear that, in part, I was motivated by the challenge of attempting to say something fresh about such an endlessly photographed subject as autumn.

The literature about autumn is full of descriptions, not just of the beauty of the season, but also of the complex ways in which the landscape deeply affects our moods and stimulates memories; of the many ways in which we use the metaphor of place to develop our thoughts and understand who we are. Writers, of course, also invariably reach for autumn as a metaphor to talk about the passing of time, and issues of loss and longing.

The images were made by moving into the flowing water either on foot or by boat, with many of the images looking underneath the surface of the river. Moving away from the comfort and familiarity of the riverbank involves the transition, from a known and well-documented landscape, into another world with its own unique sound, texture and sense of space. It is a comparable transition to the wildness that snow or darkness can confer on even the most mundane of landscapes.

In this unfamiliar setting, perspective, scale and colour are reconfigured.

While each trip to the river delighted me with new visual possibilities, creating the images was a physically demanding and an often uncomfortable experience. Standing in the fast flowing river or sitting in a spinning inflatable it was often hard to maintain balance and orientation. Visits to the river invariably included getting wet. Andy Goldsworthy perceptively suggests that you only feel the cold when things aren’t going well artistically. The difficulty of creating images in a fast-flowing river frequently caused frustration and poor results, hence it also often felt very cold.

Originally I planned to contextualise the river-based images with photographs of the river and the wider landscape made with a large format camera. It was soon apparent however that this didn’t work. Placed side by side, prints from the two settings were so obviously from different visual worlds. With such a clear clash of styles, each of the series seemed lessened by the presence of the other.

I quickly realised that the photographs would work well as a book: the variation and beauty of individual images magnified by their collection in book form into an unfamiliar visual world that would hopefully sustain repeated viewings and stimulate multiple interpretations. The writer Julian Hoffman, who had generously helped me in the research stage of the project, agreed to write an essay for the book. Julian is an exceptional writer and his captivating essay ‘Falling Away’ is everything and more I could have hoped for. Seamlessly mixing memoir, ecology, culture and topography, and without referencing the images directly, Julian’s essay is a substantial and poetic meditation about the autumn season.

A major concern with printing the book was to ensure the faithful reproduction of images that were often intensely saturated in colour. Although more expensive, I felt it was necessary to have the relative security provided by using wet proofs, in addition to digital proofs, in preparing the book. Developing and printing a photobook is a process involving seemingly endless decisions, and can certainly be the cause of high levels of stress, but seeing for the first time a successfully printed book that you have worked on for many months, finished with cover and dust jacket, is an exhilarating experience.

Much has been written about our affect on landscape, and visually, there is now a strong tradition of landscape photography that is concerned with human impact on the land. But much less has been said about, and it is perhaps a much greater challenge to record, how landscape affects us, of the many ways in which place helps us understand ourselves, gives form to memory, and shapes who we are.

The River Frome is a small and unremarkable river that runs through the urbanised outskirts of Bristol. It is not a typical place where one would expect to find the wild or the beautiful. But it’s there and it’s there in abundance.

These places matter because, just like the more grand and dramatic spectacles of nature, they have the necessary and needed ability to refresh and renew, they have the ability, even if only momentarily, to make us change the way we see and feel, to make us change who we are and who we can be. Crucially, the discovery and enjoyment of small scale, local wild landscapes also matters because they offer people a realistic and possible opportunity to begin a necessary political engagement with landscape and the environment, rather than places in far corners of the world, that can often seem both remote and beyond influence.

While it is essential for photographers to document the often shocking scale of environmental damage from economic exploitation, pollution, marine debris and climate change, I believe it is also important that photographers help to awaken viewers to the spectacular beauty and variety of wildness that still exists, and often lies just beyond their house or car windscreen, if they can only be encouraged to look. The less the natural world is known visually and imaginatively, the easier it is to dispose of morally and politically.