Simon visits the Colorado Plateau where he finds canyons, hoodoos and a bridge full of photographers

On the outer fringes of Zion Canyon, in one of America’s most spectacular National Parks, I was out for a stroll. There was a quiet chill in the evening air; a reminder of the approaching winter. As I walked along the path my right ear filled with the sound of running water: the Virgin River, flowing in parallel close by, noisily chattering over rocks and roots out of sight behind the scrub. On my left, a field of soft grasses was decorated with sinewy limbs of silvery sun-baked deadwood. A group of mule deer stood a little way off, chewing the desiccated vegetation and watching me nonchalantly. Behind them, a line of majestic cottonwood trees was illuminated by the setting sun, golden in their autumnal splendour and highlighted against a backdrop of the diminishing outermost walls of this canyon which were deep in shade. Turning the other way I followed a narrow path through the undergrowth - probably made by both deer and people, neither of which is ever very far away in this lush place on the Colorado Plateau - and soon arrived at the sandy banks of the river. Smooth red boulders punctuated the soft sand, and atop one of them shortly ahead, I spotted a blue heron standing statuesque. Through the trees on the far bank, I could see the eastern sandstone cliffs were ablaze in the setting sun, their rich orange colour reflected in the rushing waters, mixing the colours of sandstone with the blue of the desert sky.

Zion was carved over millennia by a branch of the Virgin River. In the south, it begins shallow and wide and closes in steadily and claustrophobically northwards until the river becomes flanked by almighty canyon walls nearly a thousand metres high. The heart of the canyon is lush: a verdant oasis with ferns, trees, shrubs and mosses, nourished by seeps of water that have percolated for hundreds of years through the rock, and protected by the tight embrace of the colossal sandstone cliffs. Above the canyon the landscape changes in proportion to the elevation; the higher flanks are almost completely devoid of soil, becoming an undulating landscape of giant sandstone mesas dotted with trees, cross-hatched and bleached white. Mountain lions inhabit these rocky uplands, although you’d be extremely lucky to see one.

I was ambling along a path called the Pa'rus trail with no destination in mind, only photographs to find. Aptly named after the word for "bubbling water" of the indigenous Paiute people, this trail winds gently through lush riparian habitat alongside the Virgin River. This far out from Zion’s inner sanctum the valley is broad and the canyon walls much wider apart, but although less dramatic and visited, this openness has the advantage of allowing late golden sunlight to flood the landscape in the evening (‘Pa'rus Trail’). The Pa’rus trail is normally a busy pedestrian and cycling thoroughfare connecting the closest lodgings and campsite to the inner canyon, but most visitors don’t linger, and instead pass quickly through. On this early November evening, I had the trail to myself.

Such solitude can be hard to find in Zion. It’s one of the most spectacular national parks in North America, and being very accessible by road, is consequently hugely popular amongst walkers, holidaymakers and families, and, of course, photographers. It’s a sandstone wonderland with incredible potential for photography: lushly vegetated with varied climatic zones and wildlife abound. In all the array of possibility, it offers you may think that photographers would scarcely get in each others’ way.

And yet, at the end of the Pa’rus trail just ten minutes away, there is a curious place where photographers line up on a road bridge, every day and all year round, to take near identical images of a river and a mountain. What monumentally astonishing or breathtaking subject might have caused this phenomenon? Well, it's a view of the Virgin River, some cottonwood trees and a mountain called the Watchman.

It is, granted, an ideal composition: the Virgin River curves gracefully away from the viewpoint towards the Watchman, an attractively sculpted mountain whose distinctive weathered face glows hot in the refracted rays of the setting sun. And I suppose Zion’s geography cannot help but funnel photographers closer together as they head deeper into the canyon. But upon seeing this amusing gathering, of whose reputation I had heard before my visit to Utah, I did wonder why any landscape photographer would wish to stand in a line, elbow to elbow, with so many others to capture what must be very nearly exactly the same image? The bridge has become so busy that ‘parking bay’ markings have been painted onto the road by park authorities for the positions where photographers are supposed to stand their tripods. I surmise this may have come about because the sheer numbers were starting to become a traffic hazard, as sometimes the photographers are two rows deep!

The Watchman isn’t the only mountain to have almost completely lost any sense of privacy: the mountain behind Moraine Lake in Canada’s Banff National Park appears to also be suffering from this herd-like photographic behaviour (see Joe’s photograph in his Shadowlands article in issue 65). The origin of the popularity of Moraine Lake may at least be explained by its reproduction on thousands of Canadian twenty dollar bank notes, but I’m not sure how The Watchman view, agreeable though it is, could have become such an essential, unmissable photograph for everyone to take.

Zion also has several other busy landmarks where photographers are found to congregate: the Pulpit, the Narrows, Checkerboard Mesa, the Subway, and more. Searching the internet for images of Zion, many of the same views come up, again and again, such that you might be forgiven for thinking that there’s nothing better to photograph in the whole park. And of course, it’s not only Zion: the other parks of the American desert west are brimming with such iconic views as the ‘Mittens’ in Monument Valley, the U-bend in the Colorado river, and Antelope Canyon with its famous shafts of light, to name but a few. Spectacular, beautiful and distinctive these places are to be sure; and equally surely are there daily groups of enthusiastic photographers lining up like ants around dropped chocolate, imaging the same scenes as have been done countless times before.

What could be the reason behind this collective desire for duplication? I wonder if painting enthusiasts spend much of their time serially replicating each others’ watercolours or those of past masters. Originality must be as important for photography as it is for other arts, else nothing new can ever be said; but it’s easy to get the impression that an ambition for it seems to be generally lacking, and that landscape photography for many is more of an exercise in trophy collecting. Perhaps it’s a reflection of modern life, which is rushed and consumerist with barely any time available for casual wandering and discovery at one’s own pace. I suppose visiting these famous views are hence an easy win: they can be ‘done’ with the minimum expenditure of time or effort, like photographic convenience food – Blue Peter-esque compositions that were prepared earlier. And being fine views they can be shown to non-photographer friends and family back home who might be none the wiser. But it is surely devoid of creative input - or output; there can be no message imparted to these repetitions by the photographer, and reciprocally, they cannot say much about the photographer. And with these duplications, there is a worrying side effect which is certainly noticeable with images taken in the desert southwest: since they are so similar, another way must be found to ‘stand out’. This invariably means some judicious and often garish use of the contrast and saturation sliders to inject more ‘wow’. Honestly, the colours of the Colorado Plateau are amazing enough!

I also wonder whether our ever-increasing infatuation with technology is contributing to an increasing disconnection with the natural world. Everything becomes viewed through a viewfinder or on a screen, with the images you will take having already been mostly decided before you step onto the plane. One cannot help of course but be biased by having seen so many photographs taken by others of the place you are about to visit; the clichés are always indelibly etched into your mind. Prior to my trip I fully expected to be photographing the Grand Canyon and Bryce Canyon at sunrise, and Antelope’s myriad of abstract kaleidoscopic colours. And I did so; but the difference for me is that I’m always optimistic something new can be found in any place, no matter how popular.

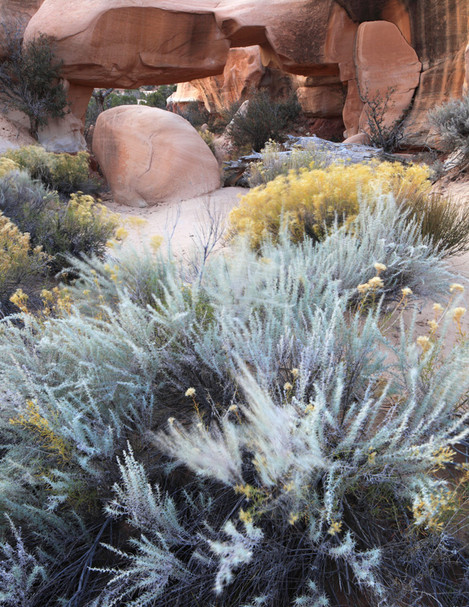

It was when reviewing my images at around the mid-point of my trip that I actually discovered my photography had taken its own direction: I found it was not views of the infamous geological landscapes themselves but rather the fragile vegetation which inhabits these sandstone environments which had taken my fascination. This seems to have begun almost subconsciously before I even arrived at Zion: when exploring the rim of the Grand Canyon, I was much more enchanted by the forests that flank that almighty yawn in the earth, where herds of elk roam in the crisp forest air, their breath drifting upwards in puffs of steam. Then, travelling northwards from Arizona to Utah, I explored some lesser-visited canyons. In Cottonwood Canyon, I discovered a Bristlecone pine standing in a dry sandy wash with towering sandstone walls all around. I was immediately drawn to its character, with hairy outstretched limbs, a background of white slickrock and a warm side light supplied by strong sunlight bouncing off a nearby canyon wall. I made an intimate portrait of this tree, which has such resilience, relying on sporadic flash floods for water and the imprisoning canyon walls for second hand sunlight, and with the delicate grasses at its feet, I tried to highlight the quiet beauty of life for plants living in a desert canyon.

It was a similar story when I arrived at a remote place of hoodoos called Devil's Garden. The two images I made there gave second fiddle to the geology: venturing beyond the main area of these sandstone stacks I found an expanse of slickrock scattered with brittle grasses and silvery dead trunks, the remnants of trees electrocuted in summer storms past. There was a palpable sense of the harsh reality of life for the vegetation here. I battled in very strong gusts of wind, with sand stinging my face and bare legs, to get an image which captured just enough movement of the grass to retain some definition whilst keeping the rest of the image free from vibration.

Afterwards, I found respite amongst some petrified sand formations, where I attempted to portray a sense of the strange environments that shelter the distinctive desert plants to be found here.

And so when I arrived at Zion for the last few days of my trip, I already knew the angle I would take: to try to depict the life which shelters within this dramatic canyon. To help my chances of conjuring some original interpretations of this busy national park, I explored mainly the periphery of the well-known landmarks. I found that there is such a wealth of subjects to discover; a variety in the nameless nooks and crannies of this canyon that offers enormous potential in this magical place of theatre and light without having to photograph any of the clichés.

Deep in the canyon, I explored a nameless section of the Virgin River. Heading in the opposite direction to where many photographers were camped, all content in making images of a giant sandstone stack called the Pulpit, I quickly found myself in seclusion. The blue sky overhead and the glare of the mid-morning sun from the far canyon wall created a vivid palette of reflections on the river’s surface, like liquid gold; the hues complemented the colours of autumn leaves trapped against rocks by the flow.

Then, I found a narrow area of unusual grasses, intricately thin like spider's webs. I noticed they only seem to grow very close to the river, and in the morning sunlight, they were lit up like iridescent yellow candy floss. An instant, instinctive draw, I knew instantly I wanted to make an image of them. Treading carefully to avoid any damage, I found a group of browned stems holding on to their seed pods which protruded through the spidery grass; this gave me something on which to hang the image.

To me, this is the joy in landscape photography - finding something unique and beautiful that I have not seen before, and that I can capture in an image.

For a few days, the weather turned suddenly colder with a low cloud base depositing snow at the higher areas of the park. Exploring up near Checkerboard Mesa there was the inevitable camp of photographers in the car park, taking their aim at this giant lump of cross-hatched sandstone which looked a bit like an iced blancmange with its dusting of snow. But with my brief firmly in mind, I wandered away down the road to find an interesting cottonwood tree with one branch angled as if huddling into the sloping shelter of another sandstone mesa at its side.

A lack of strong sunlight is unusual in photographs of Zion and so I used this temporary weather to my advantage on a walk to a place called Emerald Pools: with autumn colours at their peak, I captured a colourful tapestry of cottonwoods, pines and maples under imposing canyon walls, and an area of lushness which epitomises the scenery deep in the heart of Zion.

Time spent wandering is key to my photography. I find when in the right frame of mind, taking my time to be receptive and observing my surroundings, I’m most likely to find something that excites me to make an image. The body of work I build embodies that reaction, and that in turn has some message about me embedded within it. I would urge everyone to veer away from the madding crowds, from the hallowed grounds littered with tripod holes, and go to nameless places - and take your time, explore, search and discover what sparks your own interest. You never know, you may just find a new icon.

Back on the Pa’rus trail, I was tracking the movement of the terminator: the line between sunlight and shadow which drew across the land steadily and perceptibly from one side of the canyon to the other. The magic happens along this line, where it highlights with golden light the delicate fronds of dry grasses and the auburn of autumnal cottonwoods. Out of the dying sun’s gaze the shade soaks up a subtle cyan cast from the deepening blue sky. I’d observed and timed the route of the terminator on two consecutive evenings so I could anticipate the path of the sun's final rays before nightfall. One evening I observed an area of brittle clumps of yellow grasses become softly lit above the shaded ground. I had just enough time to set up on the tripod, tilt the focus and take a shot before the terminator moved on and the light was gone.

So I guess you might be thinking that I didn’t make my own image of the Watchman from the bridge over the Virgin River. Well, I think photography should strive to be an art, to embed meaning for and relevance to our lives and our relationship with the natural world; but I recognise it's also a hobby which should be fun. All the photographers jostling for position on that bridge were there to watch nature and the land and the light across it, and in doing so to have camaraderie with others of like minds; and of course, I have no wish to criticise them for that. Perhaps these scenes which have become such clichés are simply the pop music of landscape photography - the equivalent of Beyonce rather than Beethoven. Loud, instantly catchy but superficial, with songwriting structures and chord sequences that have all been done umpteen times before. But although I infinitely prefer Beethoven, I have been known to occasionally enjoy the odd bit of pop music. So having completed a body of work of what I hoped portrayed my own perspective of the canyonlands of Utah and Arizona: yes - I did make an image of the Virgin River and the Watchman at sunset. But, I moved a little way downstream from the bridge to do it; partly because I couldn't quite bring myself to join the horde, but also because there just wasn't any room left on the bridge to do so…

- Virgin Reflections

- Virgin Grasses

- The Watchman

- Temple

- Tamarisk

- Pa’rus Trail

- Mesozoic

- Last Rays

- Fall in Zion

- Echo Canyon

- East Mesa

- Canyon Paradise

- Bristlecone