Fran Halsall talks about one of her favourite images

Fran Halsall

Fran Halsall specialises in photographing the UK landscape, particularly the wilder parts of the coastline, moorlands and woodlands, and has a particular passion for creating interpretative images of geological formations.

After years of trying to achieve such clarity through simplicity in my own work, I have really come to admire Bernhard Edmaier’s stunning aerial photographs. I must also admit to a certain amount of professional jealousy in that his work takes him to some of the world's most interesting locations, places that have largely been untouched by human hands.

Having originally worked as a geologist, Edmaier has a wealth of knowledge to draw upon. He exemplifies the difference between looking at a landscape and actually apprehending what you are seeing, resulting in precise, yet visually stunning, photographs. Taking inspiration from the likes of Edmaier, and other photographers who really understand their subject, I have chosen to learn more about landscape processes with the aim of uncovering why places look they way they do. This research has led me to some amazing places, that are often little known, and which have provided me with intriguing rocks and unusual formations to tackle photographically. There is an ongoing argument as to whether landscape photographers should know what they are documenting. My contribution to this debate is to recognise that knowing more about landforms and ecosystems has made me a more perceptive photographer, which can only be a positive thing.

Edmaier's photographs are accurate records of geological processes yet they would not look out of place in a gallery, blurring the line between documentary imaging and fine art - distinctions that I personally find irrelevant and potentially unhelpful. Putting imagery into one box marked 'useful' and another marked 'artistic' creates divisions where none are needed.

In a ideal world all educational imaging would have the wow factor, imparting information with ease because the audience is already captivated, rather than relying on the accurate yet dull photographs that often populate academic textbooks.

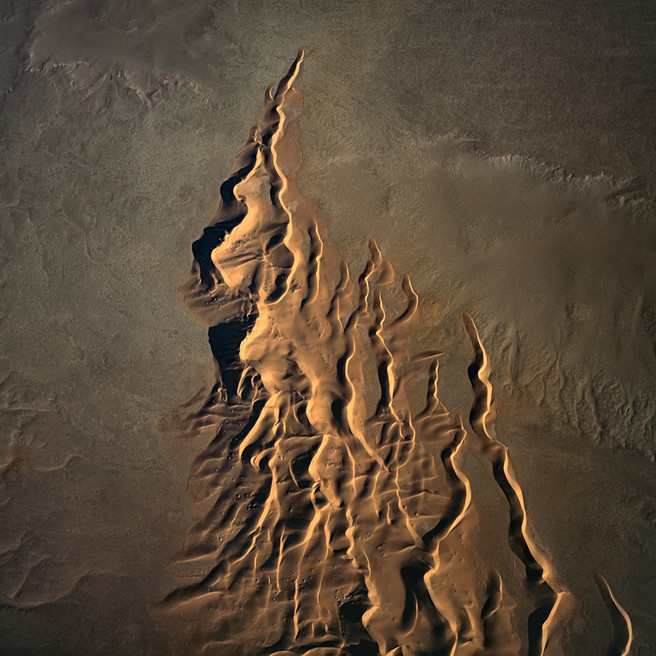

Although accessing a helicopter has never proved to be a practical option – the expense being prohibitive - aerial photographs have provided me with an alternative way of looking at the world. The patterns writ large across vast tracts of land repeat at ever smaller scales and this photograph illustrates that ambiguity perfectly. Are we being presented with an unimaginably large area of desert or a few ripples on a sandy shore? The title more than likely gives it away, although the initial impression is uncertain. Photographs purport to show reality, however such images demonstrate that the information contained therein is open to interpretation. This image demonstrates the phenomenon of scale independence, where there is nothing discernible within the pattern to indicate the subject's size. This is an idea I have played around with in my own photographs of nature's patterns, allowing a hint of mystery to enter into the otherwise strongly representational medium of a photograph.

After shooting many 'scenic' landscape images, the predominant type in popular culture, I have come to prefer making images that eschew traditional compositional structures (e.g. beginning, middle and end). Edmaier's photograph rejects conventional spatial organisation and is clearly informed by the less is more approach to composition, deftly including the minimum number of elements required. Although he is clearly pushing the envelope by using just two materials, namely sand and rock, despite this visual austerity the image still hangs onto a narrative thread. It proves a point that I have long held to be true: it takes a truly stunning subject for a photograph to succeed with only one element depicted in isolation; most photographs rely on the combination of at least two different forms, textures, tones, colours or whatever to create contrast, and it is this opposition that generates visual interest and narrative drama.

Something else that can be taken from the best aerial photography, is how to overcome the challenge of creating an eye-catching composition with what appears to be a flat surface. Edmaier's masterful use of light is a testament to choosing the right moment. What else other than the last few rays of sunlight raking across the desert's surface would produce results such as these? The eye is concentrated on the edge contrast along the crest of each sand dune, appearing all the more distinct next to the lengthy shadows and the muted tones of the rocky plain on all sides. This grey, stony expanse recedes into the background and, although subtly marked with long-dessicated river systems, is neutral enough to be a ‘foil' heightening the sense of distance between it and the highlighted crest of each dune. Edmaier understands that these edges are interesting of themselves and that the transition zone between one material and another provides a fruitful theme to explore photographically.

Edmaier has employed a typical compositional device here, namely the use of strongly directional lines; the dunes enter the frame as a broad sweep before terminating at a single point. These dunes have the feeling of definitely heading somewhere and their position is subtly weighted towards the right hand corner, slightly offsetting the otherwise central alignment. Lines coming in from corners exaggerate the sense of the eye being drawn in to a particular focal point, in this case it is that last dune as it peters out onto the rocky plain.

Photographers frequently get into verbal knots when talking about composition and the ineffable quality of balance. The arrangement of elements in this stripped-down image ably demonstrates the idea of harmonious proportion through the volume of space given to each subject. The plain occupies approximately two-thirds of the frame’s area, while the sharply defined dunes are spread out over the remaining third. This weighting means that although the dunes are visually dominant the same is not true spatially, allowing them a greater sense of potential space to flow into. Another way of thinking about it is more instinctual; the dunes do not feel crammed into the composition because there is space all around them from the moment they enter the frame.

New Book from Bernhard Edmaier

The latest book by the award-winning photographer Bernhard Edmaier presents his stunning vistas of water in awe-inspiring views of our planet.

In his seminal photography books, Bernhard Edmaier captures dreamy, colorsaturated, seemingly abstract images of earth from above. In this new volume, Edmaier looks at water—from both the air and the ground—as a source of life and one of the most important landscape shaping forces on earth.