Exploring Limitations & Creativity

Karl Mortimer

Karl is a photographer based in the rolling countryside of Monmouthshire, South Wales. He tries to find graphical simplicity in the landscape, and is partial to exploring his back garden with a macro lens in search of hidden gems amongst the shrubbery.

I recently found myself facing a bit of time in post-operative recuperation, during which I would be unable to carry or use my camera, walk any significant distances or manoeuvre a tripod. In short, I was going to have to rest and not take any photographs for a while. I wrongly assumed this would be relatively simple and the free time I was to be afforded would allow me to undertake all the image editing, printing and absorption of books that I hadn't managed to get around to for a while. Instead, only a few days into my enforced period of sofa warming I found myself much like a small child in a sweet shop being told they can’t have an everlasting gobstopper. I wanted the one thing I couldn’t have; I needed to create some images.

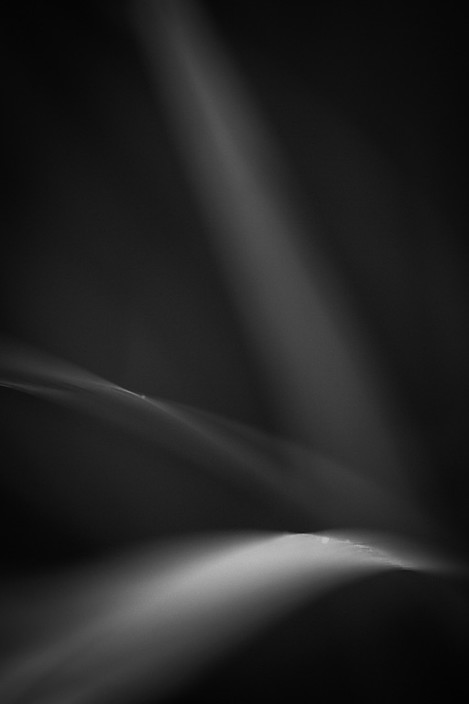

In order to create those images, I had to accept some restrictions that were being imposed upon me by my recovery. I could not drive, carry a bag full of gear, manipulate a tripod, bend down or stretch and even though I could walk, I could not go for longer than a few minutes without stopping to rest. Those constraints pinned me geographically to my back garden, and to subject matter that was at a convenient height, which in turn led to other decisions regarding camera and lens choice. On top of these imposed constraints, I chose to add some more of my own. I wanted to produce a cohesive set of work, so a consistent depth of field, wide open, and final rendering styles were decided upon even before the press of the first shutter.

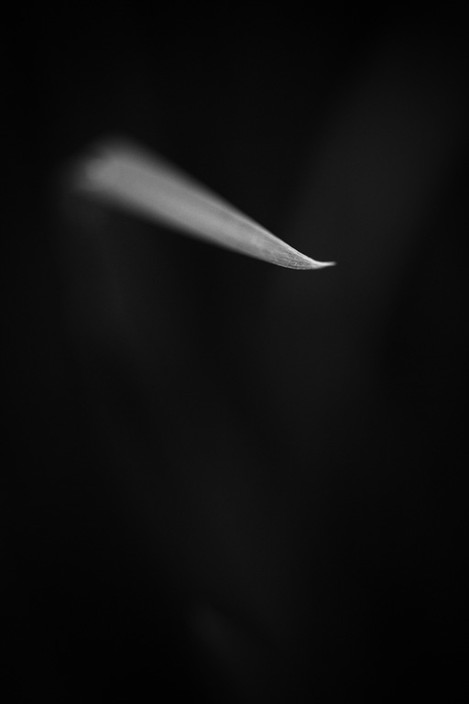

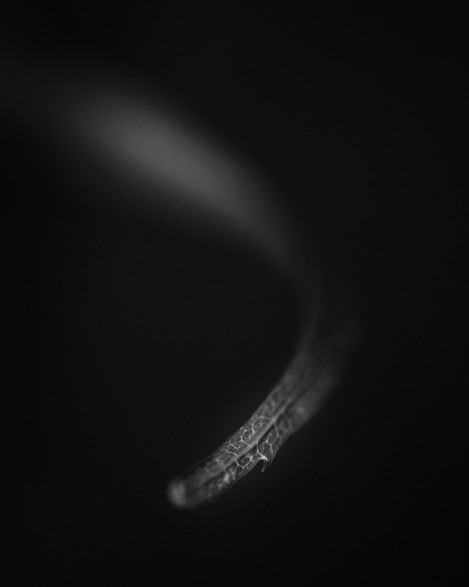

I also set myself a deadline by which I wanted to complete the set of 12-15 images. As for subject matter, I’m fortunate enough to have a garden stocked with architectural plants and foliage which at the time were at just the right stage of growth to match my impaired bending ability, but I didn't want to simply hone my macro skills, and instead wanted to use this as an opportunity to explore for myself form, line, structure and space within the confines of the image frame in a more abstracted way. In short, I’d given myself a fairly tight brief to work to, overlaid with several layers of constraints all helping to initially define and then refine that brief.

I also set myself a deadline by which I wanted to complete the set of 12-15 images. As for subject matter, I’m fortunate enough to have a garden stocked with architectural plants and foliage which at the time were at just the right stage of growth to match my impaired bending ability, but I didn't want to simply hone my macro skills, and instead wanted to use this as an opportunity to explore for myself form, line, structure and space within the confines of the image frame in a more abstracted way. In short, I’d given myself a fairly tight brief to work to, overlaid with several layers of constraints all helping to initially define and then refine that brief.

Now, the concept of applying constraints to our image making processes is anything but a new idea. The photographic press is periodically awash with advice on how we can benefit from constraining ourselves whilst shooting; only shoot with one focal length, only shoot in black-and-white, only shoot one type of subject matter, only shoot X number of frames, only shoot using a tripod, only shoot handheld, the list goes on and on. Whilst the advice itself is clearly rooted in common sense, very rarely is the benefit of doing so fully explored beyond the obvious, e.g. Shooting a fixed focal length will teach you to see and compose stronger images with that focal length; Shooting with your camera set to black and white will help you to see in black and white, understanding the translation of colours and tones from the colour we see with our own eyes into the black and white image on our computer. That advice is generally focused on helping people improve their technique, their craft, and does not necessarily explore what it can do for your creativity.

Several photographers based locally to me in South Wales, regularly produce beautiful portfolios of work, borne out of a world full of self-imposed constraints of one type or another. Rob Hudson’s ‘Mametz Wood’ project and ‘North Towards the Orison’ series, Matt Botwood’s ‘Ephemeral Pools’ and Neil Mansfield’s latest series ’29 Steps’, are all constrained in terms of their approach to composition, capture and/or also post-capture treatment, and in most cases are also geographically constrained to their local area. Rob’s work, in particular, is constrained by a piece of prose or poetry that beautifully frame and drive that body of work.

Chris Tancock's long-term projects take on many levels of constraints, from the choice of camera and lens, the time of day the work is produced, and even so far as adopting the habits of the wildlife that inhabit the landscape he works in. While Michael Jackson constrained himself for many years shooting sand patterns on a small section of a single beach, Poppit Sands in West Wales and his more recent Luminograms are produced in the darkroom ‘simply’ using an enlarger and some light, but no camera whatsoever.

However, when I look enviably at each of the bodies of work listed above, I simply don't see those constraints manifesting themselves as limitations or restrictions in their imagery, instead on the contrary I see exploration and variety, the birth and evolution of ideas, the chasing down of a creative spark or thought, the subtle ongoing conversation between the creator and the created and in some cases a genuine sense of play. I sense each photographer using those constraints not as limiting factors but instead as guiding lines and principles that help define a bounding box or world within which they can explore their ideas freely.

Constraints can give a photographer permission to focus, permission to shut out other distractions and build themselves a creative framework within which they can explore, experiment and develop ideas or concepts. Creativity can blossom in such environments, in much the same way that our remaining senses become heightened and more acute when one of them is impaired, lost or masked in some way. Our photographic instincts can sharpen, our creativity begins to flow with more clarity, and our craft improves through play. Research suggests that the most reliable way to facilitate our brain’s shift to a more creative state is first to undertake a simple, repetitious task requiring little forethought such as sorting children’s building blocks by colour. By giving ourselves constraints, such as lens choice, subject matter or a pre-determined treatment style, we are in fact removing those typically conscious decisions from our workflow and by doing so opening up the relevant neural pathways in our brain allowing us to more easily enter that creative state of mind.

Care does, however, need to be taken to ensure those guiding lines and self-imposed rules or constraints do not become an all smothering blanket for our creativity. It can be all too easy to sleepwalk into allowing those constraints to turn into a warm, snuggly duvet of comfort from beneath which we would rather not emerge, taking those easy images that require little forethought and little effort to create and ultimately leave us looking at them on the computer screen with a feeling of slight disappointment and a nagging sense of familiarity. Neither should those constraints be akin to a straight jacket, stifling our creativity and restricting our ability to react and explore. We should use constraints carefully, and most importantly mindfully to enrich and challenge ourselves.

We should not, however, lose sight of the fact that we are inviting these constraints into our photographic lives, if they begin to feel like a burden or anchor weighing us down, then we can and should shed them and move on. Some can live entirely within a world of constraints quite happily, for others, a short time spent engaging in a project or a series in this way is a more realistic proposition and can provide a well-needed kick up the creative backside. The important thing for all of us though is to be mindful of our own creative processes and know when those processes are being fed or starved by the decisions we make.

I unexpectedly learned these lessons and discovered those benefits for myself as I attempted to fulfil the brief I’d set. Initially, as I gently rocked back and forth amongst the foliage of the Iris in the border, simply hunting for abstract lines and forms in the viewfinder as tiny sections of leaves drifted in and out of focus, I would notice something in an image or through the lens that acted as a seed or catalyst for another run of images. A glimmer of something that momentarily appealed to me, a line or shape placed in a particular way or position within the frame, a curved leaf tip gently leading the eye around the frame to its own natural pointy conclusion, or the transmogrification within the two dimensions of the viewfinder of a flower bud into the gaping mouth of a newborn chick.

Sometimes these experiments went nowhere and instead led to creative dead ends, and the idea was discarded or parked, sometimes they lead to other streams of exploration that in turn themselves became sparks for ideas I have yet to pursue but have been captured in my trusty notebook for future reference. Most importantly, though, as the thread of an idea emerged, it could easily be explored, refined and honed or dismissed, all within the safety of the constrained brief. Perversely, instead of feeling constrained and restricted, I found myself feeling freer than I had for a long time with my own image making, refining both craft and ideas along with a fair amount of hugely refreshing play along with the way.

I have already seen the influence of that project and the importance of constraints in the work I've created since, and now have notebook pages covered with scribbled ideas and trains of thought I'm looking forward to exploring over the coming months and years. Try it, constrain yourself for a while and set yourself free in the process.