The life & intrinsic beauty of flowing water

Keith Beven

Keith Beven is Emeritus Professor of Hydrology at Lancaster University where he has worked for over 30 years. He has published many academic papers and books on the study and computer modelling of hydrological processes. Since the 1990s he has used mostly 120 film cameras, from 6x6 to 6x17, and more recently Fuji X cameras when travelling light. He has recently produced a second book of images of water called “Panta Rhei – Everything Flows” in support of the charity WaterAid that can be ordered from his website.

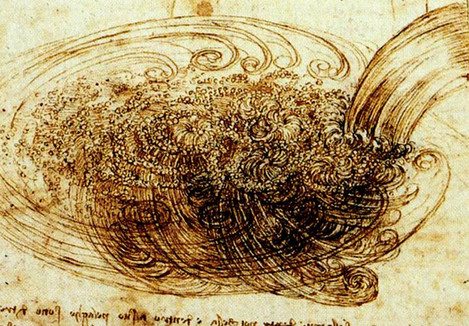

I am a hydrologist (as well as a photographer for more than 50 years). Hydrology is the study of water. It is a fascinating area of research, in part because of the real importance to human lives of the availability of water for drinking, hygiene, agriculture and manufacturing processes, but also because it is also one of the most dynamic features of the landscape. It has therefore in the past been a subject that has long attracted artists. We have long looked at the water with interest – one of the most famous documented examples being the drawings of the nature of turbulence in the sketchbooks of Leonardo da Vinci. He was one of the first people to study the dynamics of flowing water in detail (he prepared, but never published a Treatise on Water1,2), though it has been suggested that his interest was driven as much by an interest in how to make practical use of the power of water, how to improve canal design, and how to protect people against devastating floods, than in the artistic potential2.

Leonardo da Vinci: sketch of turbulence in a pool below a fall

In fact, the history of art suggests that it has proven really rather difficult to represent the dynamics of flowing water in two-dimensional images. It appears to be one of the greatest challenges for an artist. This is perhaps for good scientific reasons. Water flows are dynamic, changing constantly in response to the changing hydrology and boundaries to the flow, including the effect of the wind. The water will have varying degrees of transparency depending on water quality and sediment loads. Flowing water produces complex and changing patterns of light due to reflection and refraction. The result is that the artistic representation of water often seems to be rather poorly done.

Some of the artistic difficulties of representing water are discussed in an interesting book by David Clarke3. He suggests that one of the first and most influential treatments of water was by J W M Turner, in part because of his skill in using the medium of watercolour to represent effects of light and water in the outdoors, with a view to representing the sublime (as originally defined by Edmund Burke in the 1750s)4. Water was an essential part of the sublime – the sound and fury of mountain torrents and the dramatic presence of glaciers adding to the atmosphere as the Grand Tourists passed through the Alps. Many of Turner’s most famous large-scale watercolours are of waterfalls in Switzerland he had encountered on his travels. David Clarke also suggests that it was the dissolution of the subject matter in his watercolours (which Turner also carried over into his later oil paintings), using water as a medium to represent water as the subject, that started the path towards a more abstract art, particularly in the water-related art of Monet, Mondrian, Kandinsky, Pollock, De Kooning and Frankenthaler. He suggests that these artists (and others of course) had been all influenced by living close to and interacting visually with, water on a daily basis.

J W M Turner: Water colour sketch of sea and sky

With the invention of photography, the representation of water has become somewhat easier. Water has been a subject for images made since the very earliest days of photography, even more so once exposure times became short enough to be able to capture waves (e.g.Gustav Le Gray’s images of the sea in the 1880s). Photography has been used extensively in experimental laboratory studies in hydraulics5. There are whole books devoted to photographic studies and surveys of water images6, and we have now become used to pictures of blurred waterfalls, autumn colours reflected in rivers and lakes and, since the work of Hiroshi Sugimoto and Michael Kenna, of minimalist water stilled by the use of long exposures to emphasise the nature of the light. Water is also involved in other forms of landscape photography, of course, from the refraction that produces rainbows8, to the cloud “equivalents” of Alfred Stieglitz, to backlit geyser eruptions, and, in the form of ice, the recent spate of pictures from inside glacial ice caves and in the lagoon and on the beach at Jökulsárlón. The challenge now, as with so many aspects of photography is trying to avoid cliché (but there are some striking examples of doing so, see, for example, the River Taw work of Susan Derges, the Atlantic and Scottish Rivers work of Thomas Joshua Cooper, the Thames Studies of Roni Horn, and the early Sea Horizon work of Garry Fabian Miller and On Landscape’s own Michéla Griffiths).

As a hydrologist, I can claim to understand something about the nature of the way in which water moves through the landscape. But as already noted, in doing so the scientist has some severe constraints of how well that movement can be observed, measured and modelled. As a result, hydrology is one of the inexact sciences, subject to considerable uncertainties. The precision that scientists like is impossible to achieve (except in certain well-controlled laboratory experiments). Thus, in producing hydrological science we must allow for abstraction and uncertainty. It seems that this has carried over into my image making of water (though it is also interesting to speculate that it might have been the other way round?).

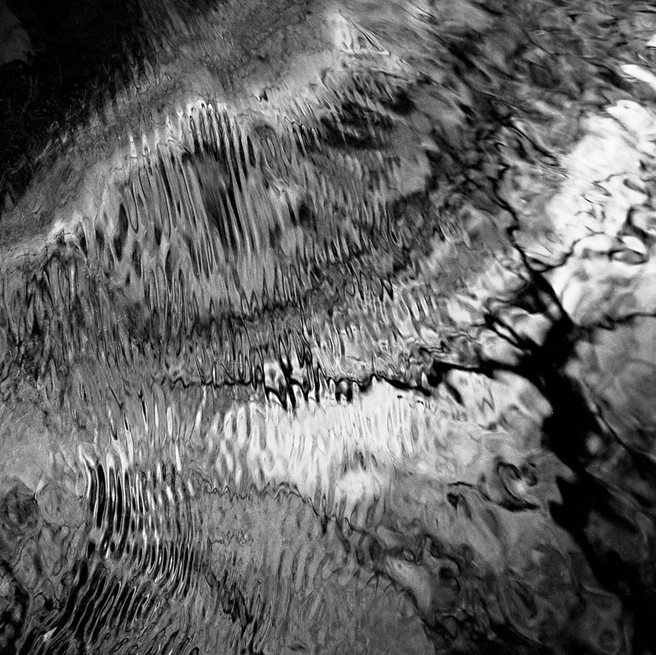

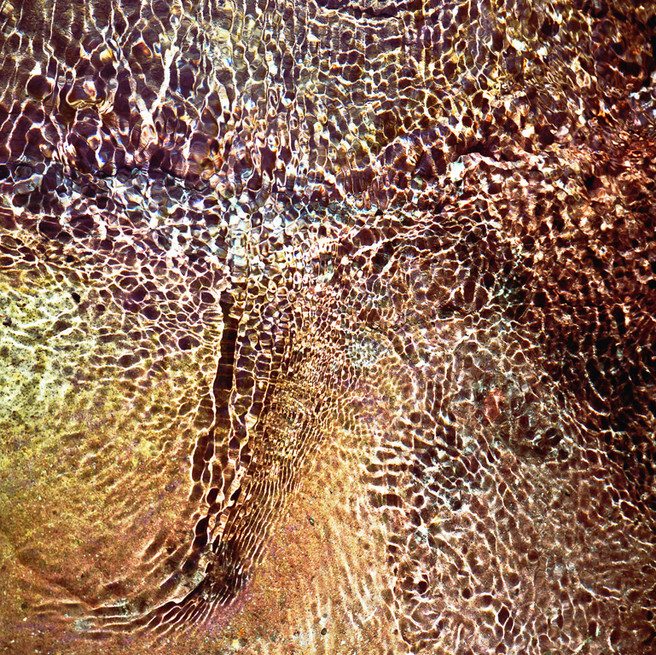

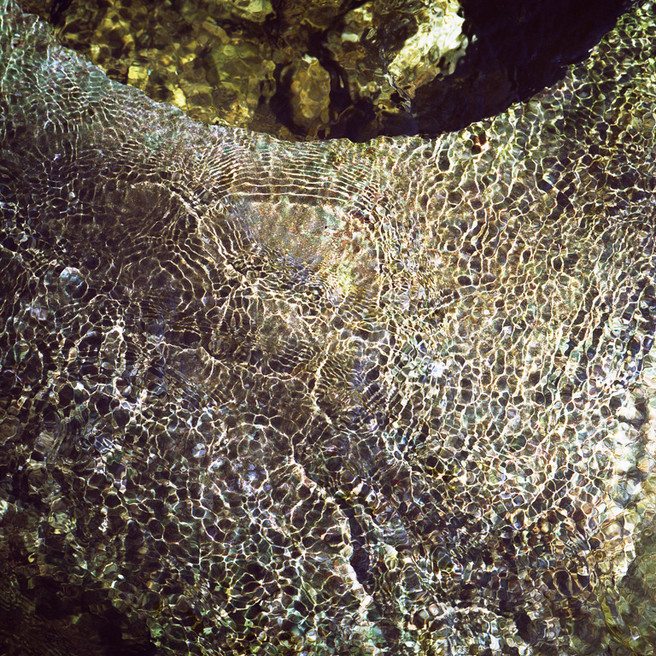

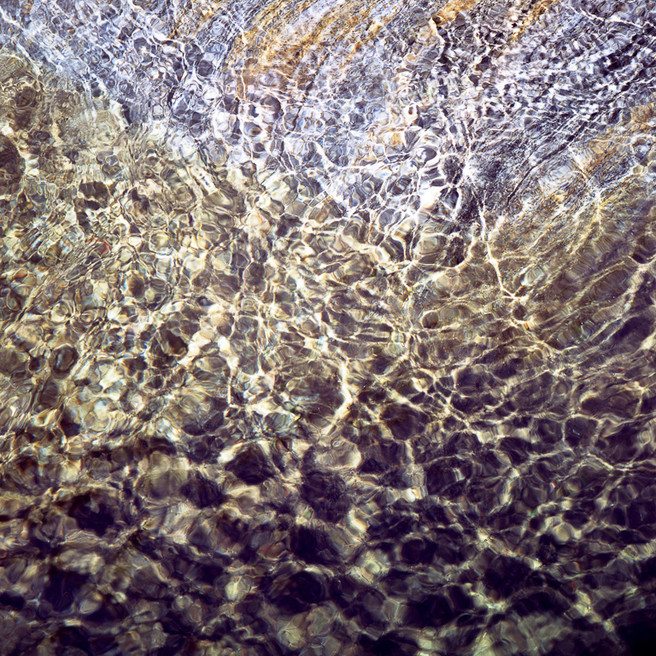

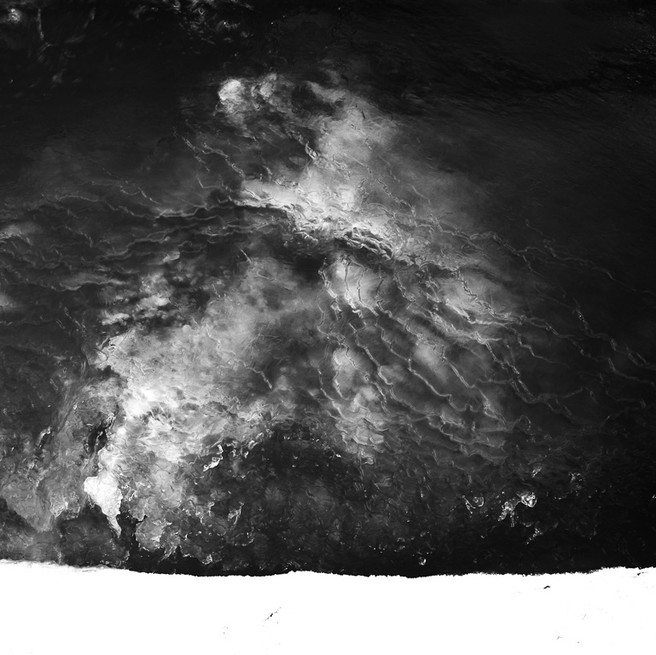

In the images that follow I have wanted to show the life and intrinsic beauty of water flows in a realistic way, while recognising the approximate way in which we can represent the dynamics. How has this been done? By trying to capture images that “feel right” – which is clearly a more artistic concept. Uncertainty also plays a role – I find some of the most satisfying images are those that require the viewer to make some effort to understand. I also find situations where there is no water to be seen, but the history of a place as affected by water is evident – the marks of past water. My hope is that the viewer will respond by valuing what is shown more highly (as hydrologists we often have to deal with the pollution and degradation of water bodies – and it is so difficult to clean up that pollution, especially under the ground, an issue addressed photographically by Edward Burtynski7,9).

Images

Footnotes

1 Asit K. Biswas, 1971, A History of Hydrology, North-Holland Publishing

2 Laurent Pfister et al., 2009, Leonardo da Vinci’s Theory of Water, Int. Assoc. Sci. Hydrol. Special Publication No. 9

3 David Clarke, 2010, Water and Art, Reaktion Books

4 Thomes Peck, 2015, Face to Face with the Sublime, On Landscape Issue 90.

5 M Van Dyke, 1982, A Gallery of Fluid Motion, Parabolic Press; M. Samimy et al., 2004, A Gallery of Fluid Motion, Cambridge University Press

6 Hans Sylvester, 1992, L’Eau, Editions de La Martinière; David Herrod, 1994; Waters of Cumbria, Creative Monochrome; Bernhard Edmaier, 2015, Water, Prestel;

7 Edward Burtynsky, 2013, Water, Steidl;

8 M G J Minnaert, 1993, Light and Color in the Outdoors, Springer.

9 Edward Burtynsky, 2003, Manufactured Landscapes, Yale University Press and 2013, Salt Pans, Steidl.