Geoff Kell chooses one of his favourite images

Geoff Kell

Originally from the North East, I now live in Hampshire with the New Forest as my local playground. I’ve always had a camera in hand but it’s really the last 10 years I’ve that I’ve concentrated on landscape and nature. I’m particularly grateful to the people along the way who have helped me develop.

End Frame has long been one of my favourite parts of the On Landscape magazine. Some memorable ones come to mind with just a brief reflection - Rene Burri’s Men on a Roof (a long time favourite image), Galen Rowell’s Rainbow over Potala Palace (great story behind the image); Joe Cornish on an Edward Burtynsky’s Iberian Quarry image (bit of a surprise initially but his commentary opened my eyes); David Ward’s image of Poverty Flats (not a surprise - brilliant photograph).

Many writers have also reflected on how difficult it was to come up with a single image - quite a challenge posed by our editor, as “favourites” come and go - new images displace the older ones as tastes change and new thought processes are inspired. Speaking of Joe Cornish, a number of contributors have picked his images and it would have been easy for me to pick another as he is a long standing photographic hero. However, I have been thinking of another image for some time, by a different author which speaks to me on a number of levels - as a metaphor, as the culmination of a personal project, and as an example of a “cross-over” image, as well as simply being just a wonderful picture. Let me explain.

Jim Brandenburg was a staff photographer for National Geographic for years - decades, travelling the world taking hundreds of rolls of film per assignment. As he says, it wasn’t unusual to take 20, 30 or more rolls of film per day and he didn’t stop until he either exhausted the potential or he was exhausted himself. Away from his family for extended periods he eventually became, in today’s parlance, “burnt out”. He quit National Geographic and returned to his home at North Woods, Minnesota. He thought of a project - a make or break a project - either he would be rejuvenated or he would have to move on and find something different to photography. He decided that for 90 days between the autumn and winter equinoxes he would take a photograph a day - just one frame. This was the mid 1990’s, the days of film - no digital preview, not knowing what he had (or hadn’t) caught until the film was developed. He was to complete his project around his home, close to the Boundary Waters Canoe Area National Park. It certainly brings a new meaning to “working locally”!

My idea of a local project might mean the local park or even pond, but Brandenburg had the scope of the Boundary Waters, stretching to over a million acres!! Although in all fairness most of his images were taken in a small section of this. For those unfamiliar with it, the whole project has a fascinating and awe inspiring story and several aspects are worth highlighting. There were days when he thought he would have to give up, days when he thought he’d messed up and days of uncertainty. Days when he managed to grab an image at the dying of the light - some of which turned out to be truly memorable. One which springs to mind was taken after dark after tracking through the woods all day and he had his wife shine a torch on a waterfall outside of his house - a wonderful image resulted but, in his commentary to the project, he wonders whether it matters that this image was “made” rather than “taken” - an interesting play on “made” or “taken” debate that has gone on for a long time. In the end, he decides only the viewer can decide.

On another occasion, he uses some ICM (yes, it’s all been done before) by picking up the tripod during a long exposure and moving the whole thing forward - a spontaneous but brave decision given the uncertainty of film and the fact he only had one go at it! He had wanted to leave an impression rather than an illustration of the woodland he was representing. This also illustrates an interesting point - whether he would have made a “better” image by having multiple attempts or whether that single spontaneous gesture spoke louder, living with it whatever came of it. I could go on; there is something to debate about virtually every image in the project.

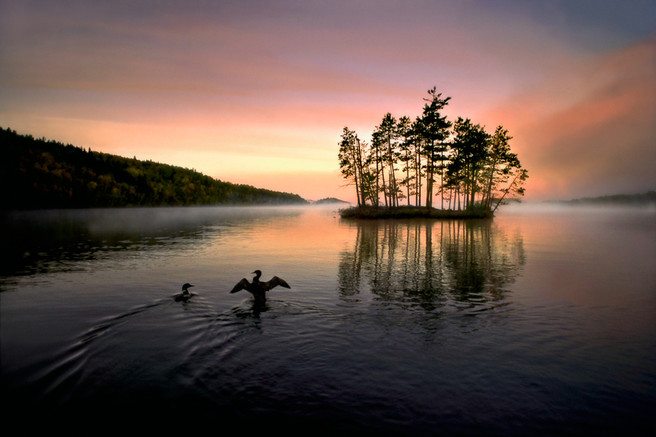

The image I have chosen is, however, also Brandenburg’s favourite from the project I believe - Day 10 Wilderness Loons. He had canoed across the lake at dawn to find two birds on the shore, one tangled with fishing line. He managed to catch it, untie it and release it. Just as it swam away Brandenburg raised his camera towards a magnificent dawn - also just as the bird raised itself up and flapped its wings as if in a thank you. Brandenburg didn’t know whether he had caught the act until the film came back - but he had, and an iconic image was born. There are many metaphors here: the kindness and giving of life; the gratitude of receiving; the wonder and beauty of nature. For me, there is also a sublime element to this image - an awe inspiring dawn and the tiny frailty of life.

This also raises another question: is it a landscape photograph? Is it a wildlife photograph? Is it a nature photograph? Does it matter? I would argue not, it is a stunning image however you look at it. Landscape inevitably includes those things in our environment, be it animal, man-made or natural. It undoubtedly has wildlife in it and it is of a natural history subject, made within the landscape. We can often get hung up on genre specific images but Brandenburg’s image crosses those boundaries. Our European photographer fellows don’t seem to get so hung up on it I feel and I think it makes for a healthy approach to photographing the outdoors, however, we may wish to perceive it.

It is fascinating to think of how this project was achieved. There were probably very few people in the world capable of producing such a project at the time and Brandenburg comments on how the antithesis of having just one image to make compared to his many in a previous life taught him a lot. A lesson, no doubt, many of us could do with learning. It is fascinating to think how all of his experiences, his visualisation, his feelings, were focused so intently on that one image per day. At the conclusion of the project, Brandenburg notes that it sat in a draw for two years - he had done it purely for himself and describes it as the hardest project he had ever done. Another lesson - wise writers in this magazine have previously noted the importance of "flow" and personal expression as opposed to recognition and plaudits. Brandenburg, in the end, achieved both of these with National Geographic persuading him to publish - it becomes the North Woods Journal, followed by his book, Chased by the Light, something he will be remembered for as much (if not more) than his wolf pictures or any of his other international awards.