Landscapes of tragedy

Amy Warren

I am a young photographer based in the South West of England. My work is centered around creating narratives which document the relationships between man and the landscape, with particular focus on leisure. My practice is based around combining my passion for the outdoors with photography, in order to produce long term projects.

On the afternoon of the 2nd of February 2018, I witnessed an accident which truly shaped my practice as a photographer. When out filming two climbers at Avon Gorge in Bristol, tragedy struck on the cliff face just next to us. A climber had fallen, and his climbing partner ran over to us, pleading for our help. As I stood looking up at the cliff face, I could just about make out the rope which the climber was now at the bottom of, indicating the length of his fall. Rescue teams worked tirelessly for the hours that followed in an attempt to save the climber, however, they were not successful.

This incident, which will forever hold a place in my mind, had a strong influence on a recent project - ‘Buried in the Rocks’ and became the first location I shot for the project. After witnessing the incident, I began to research whether there had been any other fatalities like this one. At the time, in my state of naivety, I had not even considered that death could occur in such way, in doing an act that you have control over and you are doing because you enjoy it. Through my initial research, I found more fatalities like the one I’d witnessed and learnt that there were not just a few of them. Over the last 30 years, England and Wales Mountain Rescue have reported 91 deaths relating to climbing incidents alone and this number continues to grow.

Over the last year, I have been researching and planning visits to these locations to create a narrative documenting these tragic events. Before even picking up the camera, there was a huge amount of pre-planning that went behind a shoot. I’d find out as much as I could about the fatality from news articles as well as from the Mountain Rescue blog. This would provide me with information about both the incident and the location where it happened. From this, I’d move onto researching the location to put myself in the best position possible to be able to find it. I’d plan all my routes out on maps as well as printing off photos of the location and any details that could help. A lot of the time, I was looking for a very specific detail on the rock face to pinpoint that it was the correct location. I wanted to be as accurate as possible within my imagery so my main method was to hike to the specific grid reference relating to the fatality.

I was able to photograph 38 locations which does not directly reflect the statistics from Mountain Rescue. The main reason for not photographing them all was because I could not find enough information about them. For obvious reasons, Mountain Rescue is unable to share information about the fatalities so, therefore, I was often relying on news articles and then using the dates to search the Mountain Rescue blog for the same incident. This meant I didn’t have much control over where I was going to shoot. Although this was frustrating, it was the only way I could do the project as I knew I had to be as honest as possible in the portrayal of these events.

Each journey to a location came with an aspect of mental challenge. I often had the lingering feeling that the path I was walking on would have been the same one that the climber took just a few hours before his or her last breath. These thoughts sent shivers through my spine but after photographing a few locations, I think I became slightly immune to it. It became something I had to do. The more fatalities I found, the more of a problem I felt this was. I was utterly shocked that so many people had died doing what they love - it was supposed to be fun after all, right? Further research around the story would often identify where it went wrong - there were stories from gear not being put in properly, to climbers leaving their helmet at the bottom whilst they climbed to the top, to only slightly misplace a foot and fall to their death.

My personal background within the outdoors meant that this project was do-able for me. Without the understanding of navigation, there wouldn’t have been a chance for this project to be capable of coming together. I am currently training to be a Mountain Leader which gives this project another level of meaning to me - a more personal one - in that I will one day be responsible for the safety of other people in the mountains.

The weather conditions and type of light I was shooting in didn’t particularly bother me for this project. I didn’t choose a particular season or time of day to shoot in because the project wasn’t about creating a specific look. What was more important to me was being honest and moral. I wanted to capture each place in the most realistic way possible. In addition to this, I was limited on time as I could only afford to go away for two or three days at once. This meant waking up to be at my first location for sunrise and shooting right up until sunset. It also meant I couldn’t be picky about the weather; I had to get out, no matter what the elements threw at me. I think my longest day was in Snowdonia where I was at Dinas Cromlech at 6am and photographed five locations throughout the day.

The trips were long and weren’t always successful which meant that the project needed a lot of time dedicated to it. The closest location I visited was an hour’s drive plus an hour’s walk from home. The weather also had a huge impact on what I did. The first time I visited Crib Goch in Snowdonia, I was greeted with fog and torrential rain. I had the camera out for 5 minutes before heading back down the mountain, for my own safety but also to save the kit. This resulted in a second 4-hour drive to Snowdonia a few months later. The second time, the weather conditions were much better which hugely influenced the shots I got; I was able to get up onto the ridge and explore much more within the location whereas the first time, I wasn’t even sure if I was pointing my camera at the correct ridge.

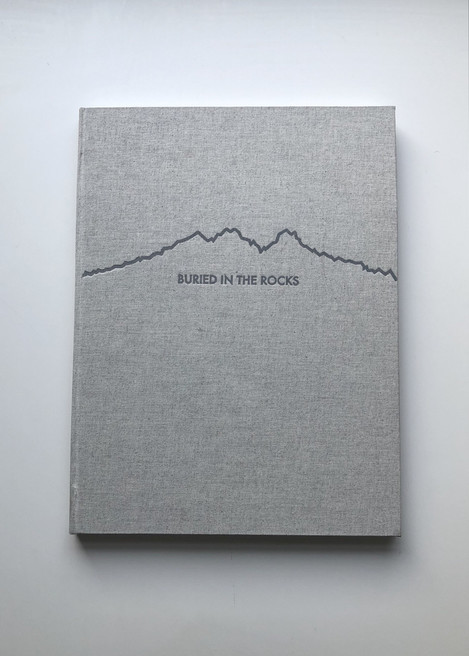

From the beginning, I knew I wanted the final outcome of the project to be in the format of a book. The narrative lent itself to be a book and as the project was long-term, it worked to have such a well-considered ending.

Initially, I had intended on having a location per double page spread to put full emphasis on the single person’s story. I imagined the full spread to be one image of the entire rock face. As the book evolved, I started to realise that I needed to shoot different angles and from different distances; I shot the crags in every possible way so that I had options when it came to the layout of the book. There was also a point halfway through the project that the way I’d photographed the crags meant they’d all have to be left hand pages. So, moving forward, I shot everything else to work on a right-hand page. This made the development of the project much more of a fluid process as I was constantly referring back to how the images were working together.

The final book is still in development; I’ve made a few copies and will be printing a larger number over the next few months. Recently, there has been a lot of news from Mountain Rescue about the growing problem with people heading into the mountains unequipped - most of the time they are referring to hikers more than climbers but the lack of ability to prepare for the worst catches the best of us out. Seeing the pleas from Mountain Rescue for help with getting the message out to the public, only confirms for me the importance of the project I have done and may continue to do. There are still many locations out there that I haven’t photographed which gives the potential for this project to continue. However, I feel the book has provided a natural end to the project and has successfully portrayed the narrative.

- Giants Cave Buttress, Bristol

- Dinas Cromlech

- Crib Goch March 2018

- Crib Goch October 2018

- Dow Crag, Lake District

- Isis Area, Swanage

- Glyder Fawr, Snowdonia