A Public Service Announcement!

Tim Parkin

Amateur Photographer who plays with big cameras and film when in between digital photographs.

I don’t know if it was before or after my trip to London that I decided to write an article on ticks and Lyme disease but since I did start writing, my level of Lyme disease paranoia has been a bit scary. As a photographer, I’m out and about in the landscape quite a lot and in the Highlands area where we live, we’ve had specific warnings about the prevalence of the disease. I’ve taken some precautions, I’ve treated my socks and trousers with Permethrin and rarely wear shorts (and have horrendous pale blue legs as a result) and thankfully have not had any ticks in the past couple of years. However, after hearing about a handful of locals being treated for Lyme disease and recently discovering that it’s the smallest, almost invisible nymph stage of ticks (about the size of poppy seeds) that are the most likely to give you Lyme disease, I thought it worth investigating further.

I mentioned London earlier and it was on this trip to help with the Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition that I think I started my worry about Lyme disease. The day after arriving I suffered from a horrible case of sinusitis which included raised lymph glands and a stiff neck. During the journey back I picked up my ‘to do’ article list for On Landscape and picked out the ticks/Lyme article to develop (was this subliminal? maybe). As I worked my way through this I started to discover some quite scary things about ticks and the disease.

Lyme Disease and Ticks

Despite the rumours that Lyme disease was introduced by the US government, it is thought that it actually has a very long history, along with many other tick distributed infections. In fact, it is probably safe to say that ticks have been one of the primary distributors of illness in history (after mosquitos). We discovered the association between ticks and these infections early in the 20th Century but we only really learned some of the idiosyncrasies of how these infections work more recently. The type of bacteria that causes Lyme disease is called a spirochaete, a spiral shaped bacteria that is also behind Syphilis and other relapsing fevers i.e. illnesses that recur many times. It is also, possibly, the bacteria that cause Alzheimer's! Spirochaete have an extraordinary ability to hide within the human body (due to lack of proteins on their surface inhibiting immune response for instance), and they can also mutate away from immune reaction and return in force. It is also difficult to culture them outside of the body (two reasons why diagnosis is difficult - tests may take place between bouts or may not return enough material to diagnose).

One of the scariest aspects of Lyme disease is its resistance to antibiotics. Even if you catch the signs early and your doctor is aware enough to provide a rigorous course of antibiotics, there is still a chance (about 10%) of seeing symptoms for many years after (see Post Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome). The reason why isn’t totally understood but it could be the ability for the bacteria to get past boundaries within the body that are supposedly resistant to infection (the meninges for instance) which can give neurological symptoms even after strong antibiotics or it might be leftovers of the bacteria or neurological damage. And the symptoms can be awful, in some cases deadly. Memory loss, palsy, muscle failure, dementia, heart disease, coma, paralysis - you name it, Lyme disease seems to be able to cause it.

That such a virulent disease has no vaccine is quite odd. In fact, Lyme disease did have a vaccine but the ‘anti-vaxxers’ were so vehement and combined with the modern litigious nature of society, it soon became uneconomical. The only vaccine available now is for your pets - which is quite insane!

Symptoms

So, after my sinusitis and the start of my article, I started to feel odd aches and pains, especially an odd ache in my shins. As I was researching Lyme disease anyway, I looked up both sinusitis and shin pain and lo and behold, they are both symptoms! “OK”, I’m thinking, “Get your head together, you’re being paranoid. If you had Lyme disease you would get the target mark (see photos below).”. However, it turns out only about 60% of people get the classic bullseye mark. Oh dear - now I’m worried. Then I find an odd mark on my ankle with a bite in the middle which has a sort of ring shape. Fortunately, the aching and the marks could easily be explained by the large amount of climbing I had done in the previous week and I had also been shifting of logs from a forest nearby so is probably one of a bunch of bruises I got. The ring-shaped mark on my ankle could just be one of those bruises and the bite is almost certainly a midge bite (just like the other two nearby). As I’ve mentioned, the non-specific nature of Lyme disease just makes you paranoid. I wondered if I was just a victim of confirmation bias and so picked a random set of symptoms that I’ve had over my life and checked whether they were also symptoms of Lyme disease - and yes they were. It turns out that Lyme can cause a vast number of symptoms.

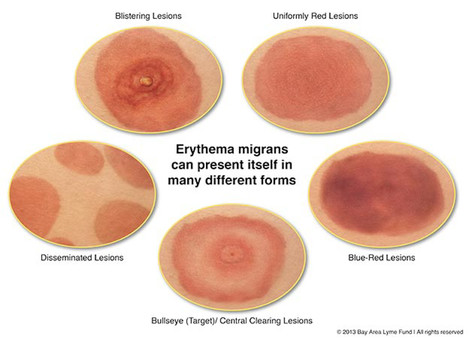

Here are the range of possible Lyme disease rash patterns. Not all instances of the disease have the bullseye rash!

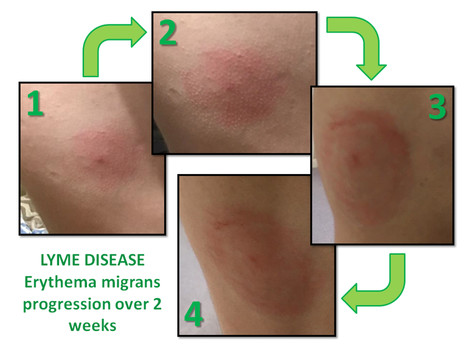

The progression of the bullseye rash takes multiple weeks. A growing rash is the main thing to look out for if it's not a bullseye

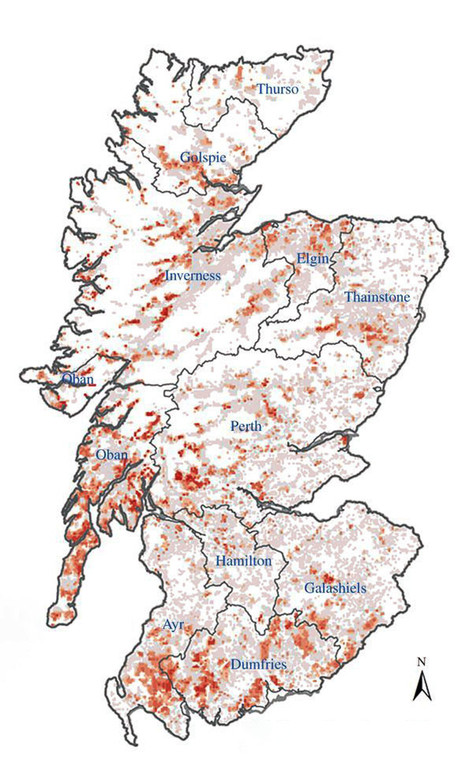

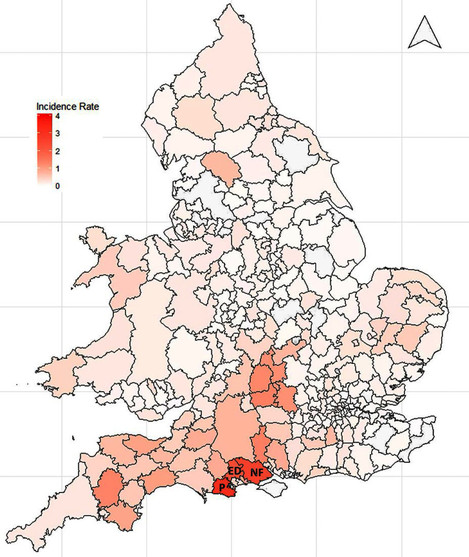

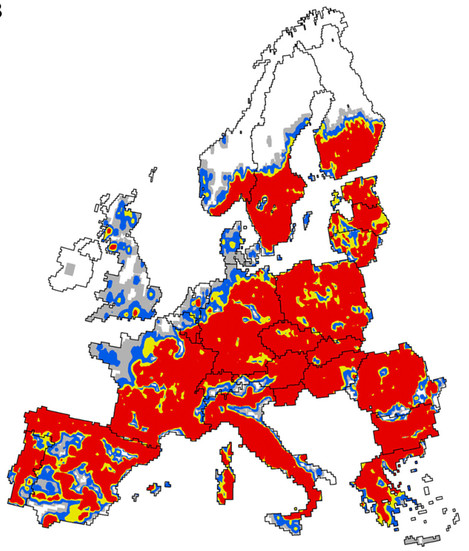

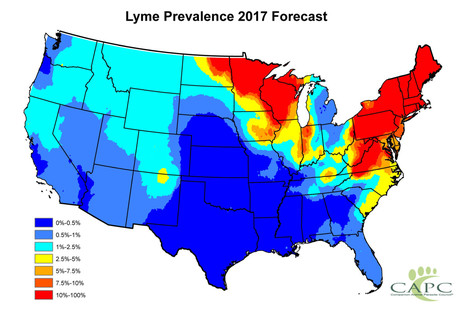

Geography of Lyme disease

Lyme disease may have got its name from a town in Connecticut in the US but it’s a worldwide problem from the UK to Australia. It’s odd that it does have a geographic distribution within these countries (i.e. some places ticks carry it, some don’t) which is probably to do with the environment for the disease pool, small mammals, and the weather conditions for ticks (not too dry). Shown below are distribution maps of the US, Europe and details of the UK drawn from various sources. Within these country boundaries, the hotspots are probably grassy areas with leaf litter i.e. woodland and brackeny paths.

Preventing Lyme Disease

I now realise that because Lyme disease is so hard to spot, diagnose and treat and it’s subsequent debilitating symptoms, it’s absolutely essential to spend the time trying to prevent getting bitten in the first place. And don’t think that because you don’t walk in the wilderness that you’re not at risk. It seems the most dangerous activity is walking your dog in semi-urban areas! Many guidelines say to avoid grassy areas and stay on paths - like that’s going to work for us landscape photographers!

So what can we do to help prevent getting bit. The good news is that the transfer of enough bacteria to cause a problem takes an average of about 24-36 hours and so you have enough time to check for them and remove them. Symptoms don’t normally appear for a couple of weeks either so if you do get bitten, make a note of when you did so you can check later.

Understanding how Lyme disease hosting ticks find you might help also. Unlike many insects, they don’t chase people, jump or swarm, etc. In fact for most of their few years alive they just hide in the leaf litter. When they want to eat, once a year perhaps, they climb up the nearest plant, probably a blade of grass or a branch of a shrub, and wait for something to pass. They detect the heat, lactic acid and/or carbon dioxide and then wave their arms in the air in a process called “questing”. At the end of the arms they have articulated hooks. If you get within range, they ‘velcro’ themselves onto your clothes or hair. Once attached, they spend a few hours climbing, trying to find a nice warm crevice, quite often just a place where tight clothes meet skin, underwear line is common or a crease in the skin behind a knee or armpit. Once there, they then start of “dig in”. If you’re sitting in one place however, you may also encounter some nymph ticks as they wander in the undergrowth. Here’s a good video about how ticks ‘work’.

Avoiding Getting Bitten

You can take some reasonable steps to prevent them latching on in the first place. The most effective repellant strategy is to treat your clothes, especially your socks and trousers, with Permethrin and also to spray your ankles with DEET (or Picaridin e.g. Smidge but it doesn’t work as well as DEET against ticks). On top of this, be wary of picking up ticks from your rucksack or coat as you sit down to take a break. A buff treated with permethrin goes some way to preventing ticks reaching your hairline (where it’s hard to check for them).

This isn’t meant to be a comprehensive guide on what to do, I’ve decided to post this article just to raise some additional awareness of a few facts I’ve discovered that weren’t obvious from the literature out there.

- You don’t have to be an adventurer to get ticks, more people encounter them in semi-urban areas and parks than in the mountains

- You’ve got 24 hours to find those ticks after any activity so check (and try to get a partner to check perhaps - even if only occasionally for bullseye marks).

- You’re more likely to have a problem with nymph stage ticks and they’re very easy to overlook. Wearing light clothing helps you spot them.

- Permethrin on clothing is incredibly effective in killing ticks or making them drop off or quickly die if not. You can buy pre-treated clothing from Craghoppers - Nosilife brand socks, pants and trousers make sense, Buff also make treated Buffs. Alternatively, you can spray on Sawyer’s Permethrin to make any clothing insect repellent (be aware it can kill cats until it is completely dried out though).

- Finally, don’t get paranoid like me, just be wary of odd, unrelated symptoms and keep an eye on odd skin marks (marking their boundary with a pen is useful. If they grow then see a doctor).

I’m 99% certain my own symptoms are unrelated but the power of the mind to make you worry is incredible. The vast majority of the time you’ll be worrying unnecessarily but it’s worth being aware of these things just in case.