Reshaping the landscape

Hal Gage

Gage has mounted dozens of solo exhibitions and been in hundreds of group exhibitions between 1986 and the present. In 2004 he mounted his first museum exhibition, “Ice: a personal meditation.” It subsequently toured the state of Alaska to museums in Fairbanks, Homer, Juneau, and finally to Portland, OR. In 2011 Gage mounted two followup series titled “Strangers: Tidal Erratics of Turnagain Arm” and “Ice Abstractions” that toured in Alaska. Most recently his series, “Glacial Silt Patterns” has toured Alaska. It was featured in the LensWork anthology, Seeing in Sixes, and several exhibitions and competitions nationally and internationally.

Gage has won several national and international awards including the Sony World Photography Award in landscape photography. He has twice been honored with a Rasmuson Foundation Individual Artist Fellowship, and produced four public art commissions in Alaska and Washington. His work has been exhibited extensively throughout Alaska, and has shown in Canada, Eastern and Western Russia, England, Germany, East Asia, and numerous venues throughout the United States. Hal Gage has published 5 books of his work: Ice: a passage through time; Strangers: Tidal Erratics of Turnagain Arm; Gravel Quarries: Alaska; Urban Dance; and Train Trip.

He lives with his partner the writer Jean Ayers, in Anchorage, Alaska.

Ted Leeming

From traditional landscape and the impressionist, to more recent explorations of land use, climate and biodiversity, my work centres around an evolving consideration of place that forms the ‘Zero Footprint’, low carbon concept I share with my wife and fellow photographer, Morag Paterson. More recent works include the collaborative Energise, Fantastic Forest Festival and Artful Migration residencies, Where the Wild Things Are, and an immersive ‘Commute’ - by ebike - from Scotland to Italy. Find out more about our work please visit our blog, “Wanderings of a Photographic Duo”

His description of the photographer as an artist is alone sufficient to relish this interview with Hal Gage. His creative journey spanning 4 decades, exploring not just the technical elements of the medium but the emotive, results in images of personality, strength and depth that become ever more powerful and relevant when considered as bodies of work. But for me, with project timeframes ranging from 5 to 20 years, it is the focus towards subjects of personal artistic relevance that resonates most strongly (that and rating “This is Spinal Tap” and “Blade Runner” as favourite movies obviously!).

I strongly advise you take a cup of tea or glass of wine, relax with an adequate amount of time, then contemplate for yourself - as Hal suggests - the beauty and the messaging contained within both his words and this beautiful body of work.

Firstly, perhaps you could tell us a little bit about yourself and your photographic practice.

As a child, I was always fascinated with drawing. In high school, my interests turned to music. While working in cover bands as a drummer and lead guitarist, I began composing and recording my own music, all the while continuing making visual art. At university, my painting mentor turned me on to photography (not sure if that was a commentary on my painting skills!). After I bought my first camera, I never looked back. Forty years later, I am still making photographs.

I work in thematic bodies of work that take between 5 and 20 years to complete. Novelty is not my friend. I need to get to know a subject over a long period of time, to listen and hear what it has to tell me. I found my voice kind of late in my career. I started out in the mid-70s following the luminaries of the time like Ansel Adams and Edward Weston. I got sidetracked with the technical aspect of photography (developers, sensitometry, optics… you name it, I studied it) before I allowed the intuitive side, I had cultivated in my painting days, to emerge. I think I ultimately benefited from that “techie” period in my life, but because of it, I didn’t really find my voice as an artist until the late 80s.

After a long career working in the “wet” darkroom, I made the switch to digital in 2008. I mention that only to say that I have a long history with the traditional aesthetic of photography. Nothing really changed in the transition, except I just became that much more productive. Because of my background in graphic design and desktop publishing, I was an early adopter of digital printmaking. In the late 80s and early 90s, I worked with laser printers, imagesetters, dye-sublimation printers, digital negatives for the darkroom, and Iris prints to produce my artwork. Once cameras could produce high enough resolution to rival or equal film, the switch was a natural move.

How did you become interested in the Ice series and glaciers in particular? What were your motivations and how did you deliver the project?

In Alaska, winter is a ubiquitous part of life. After decades of trying to ignore it, I decided to embrace it. Back in the darkroom era, I focused on ice as a subject for its unique beauty and for its symbolism for our changing environment. The series developed organically and branched out to several sub-series. Ice is primarily a winter subject, so I started visiting glaciers in the late 1990s. There I found a subject worthy of study and available year-round.

How did that bring you to photograph glacial silt?

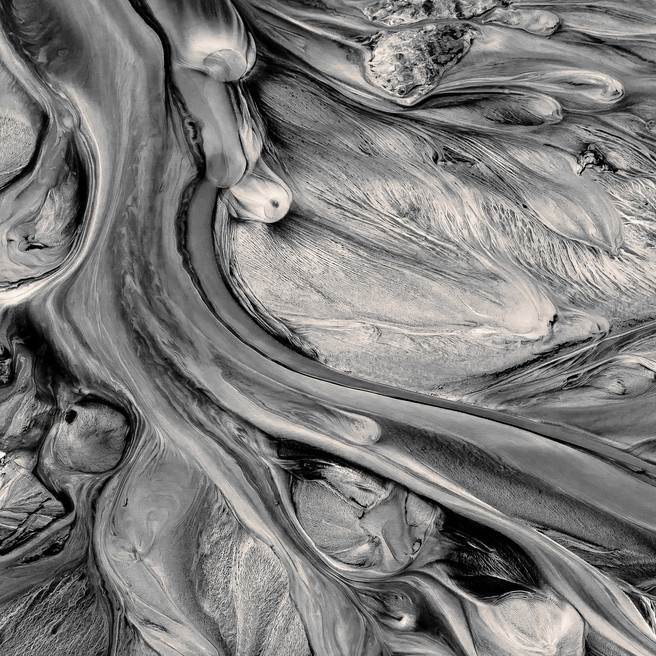

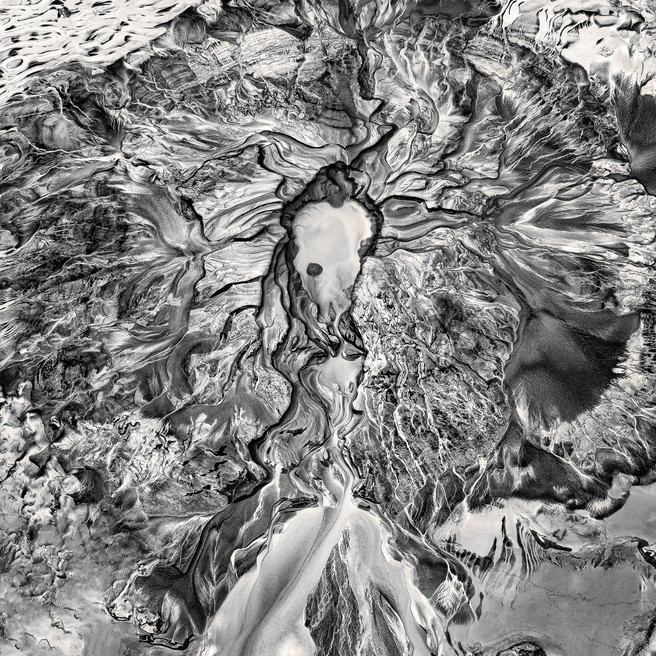

After completing the Ice Series, which premiered at Alaska’s largest museum in Anchorage, and travelled around the state and on to the continental US, I continued to work on familiar subjects. After years of looking at the glacier's soaring seracs, wind and water carved caves, and shapes or patterns in the ice, I started looking down at my feet. There I found a microcosm of the ecosystem of our environment. Water goes through its cycles, and ice and water move boulders and fertile soils, transporting them down the deltas. Erosion reshapes the landscape and makes and remakes the world around us.

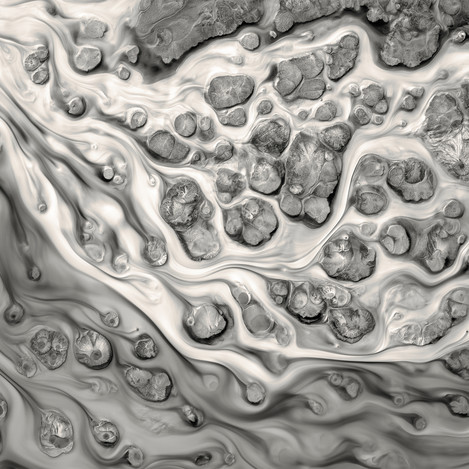

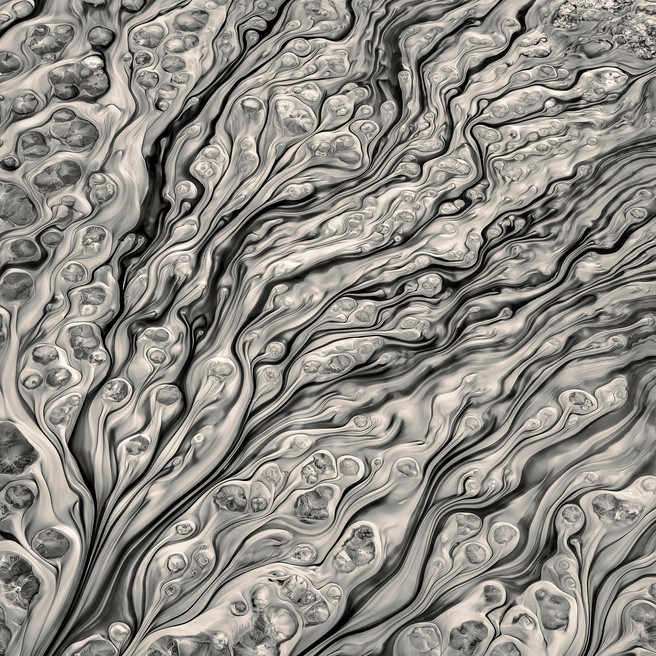

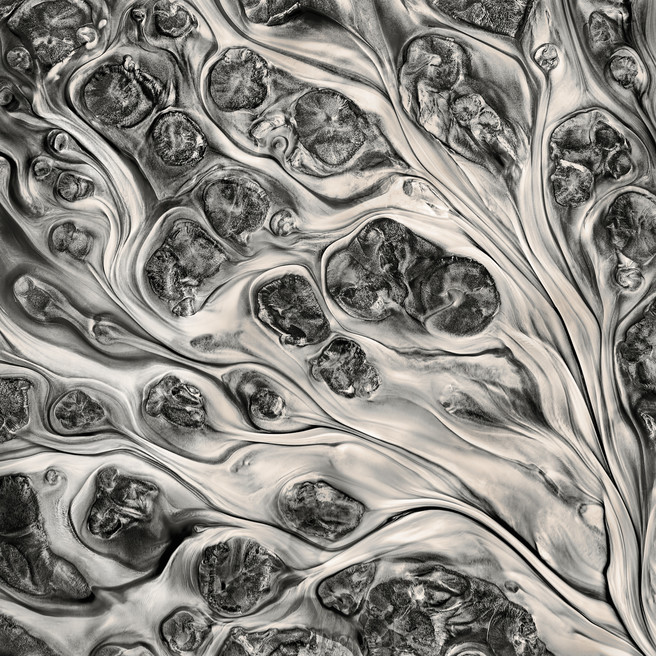

The shapes and patterns in the images from the Glacial Silt Series seem an obvious subject for photography. However, these patterns exist and are often hidden in a subtle and narrow range of tonality. It takes considerable time to “see” the shapes and patterns in the slow flowing glacial silt. With the use of daft image processing, the patterns emerged. Their beauty belays the circumstances that have created them. As the average Earth temperature continues to raise (doubly so in the Arctic and sub Arctic), glaciers melt and recede leaving behind a moraine of rocks and soils scoured from the mountain tops and valleys. The melting waters from the glacier slowly carry the finely pulverised rock (glacial flour) in minutely shallow rivulets. The Glacial flour, mud, and tiny pebbles accumulate into strange and unexpected patterns. Although barely visible to the naked eye, the subtle patterns of grey on grey can be drawn out of the digital file through a careful use of software processing to make the final image.

What have you learned from the experience?

Each series I create has its own learning curve. Working slowly and being mindful to listen to what the subject has to tell me, brings me closer to nature and the spirit within. Couple that with advances in image-making technology, and I gain a wealth of knowledge and skills. It’s hard gauging what I learned from this project since it transpired (like so many of my projects) over 20 years.

When I started out working with ice, I knew little of climate change. But, a few years into it there was a lot of speculation on the subject. I can still remember bantering back and forth with a science journalist (who ended up writing a piece for my exhibition, Ice: a personal meditation, on the physics of ice) about whether climate change was a fact or still just a theory. He was a bit of a sceptic, and I was convinced. That has been a big part of my motivation in working with ice. I feel that ice is the perfect symbol for all of human-caused environmental degradation.

What measures can we all take to be proactive in the discussion?

Photography (like any art mediums) can be something that we hide behind while looking at the world around us. Although photography–almost by definition–is an experiential pursuit, as photographers we often allow the camera to stand between us and the subject as passive viewers of the world. Once made, the image can become a flash point of conversations. I don’t think it’s up to the artist to create or drive the conversation, but it is incumbent on us to look, observe, and see the world in a new and unique way.

Which photographers inspire you and why?

As a young artist, I was first inspired by the surrealists and the impressionists. Max Ernst and Paul Klee were my art heroes. Ernst’s mastery of the grotesque, detail and organic shapes and patterns were an inspiration to me as a painter. Klee’s sense of arrangement and his part in the Bauhaus movement challenged me to concentrate on arrangement in a 2D space. This was all long before I threw myself into the study of photography.

Fast forward 40 years: today I find inspiration in many of my contemporaries. My interests in photography range widely. Landscape artists like Robert Adams, Camille Seamen and Mitch Dobrowner are essential parts of the conversation of art. Closer to home, artists like Charles Mason, Dennis Witmer, and the late Barry McWayne continue to inspire me. Street and social commentary photographers like Garry Winogrand, Simon Norfolk, and Martin Parr are all artists I hold in highest esteem. There are many many others. It seems that every day I come across a new photographer who captures my attention. The Internet has made so many voices heard and allowed me to see so much work, this truly is a new golden age for photography. In my mind, the key is to be someone who is adding to the conversation of art, not just repeating what has already been said. A good grasp of art history helps (not just photography, but all mediums). That is what “finding your voice” means to me.

All your work has an environmental or social impact aspect to it. How did you plan the images that you wanted to capture - both in terms of locations and messages that you wanted the stories to tell?

While that may be true, thoughts of environmental and social issues come long after I make the images. I guess I’m old-school. Aesthetics are my first and only thought when out in the field. I suppose there is a subconscious motivation going on in the back of my mind. I am very concerned about the current state of the world. Since I am out in the environment when making art, climate change, pollution, and man’s impact on the land have a great influence on me and my subject of choice (nature). When I make photographs, I look for things that interest me. Nature is beautiful and being in it rejuvenates my spirit, but that’s not always enough to bring me to the epiphany of making art. I look for something new and different in my environment, and that usually is the metaphoric footprint of humans. It’s usually after making photographs for a while, that I start to see a pattern in my catalogue of images and a theme emerges. Maybe it was always there to begin with, but wasn’t a forethought in my mind. Once a theme emerges, I start fleshing out the concept into what, I hope, becomes a cohesive body of work. That requires me to revisit locations over and over again. It’s rare for me to create a body of work from just a few passes at a location and/or subject.

When I teach, I tell my students, when you find a subject that grabs your attention, photograph it from every angle, in every way possible, before moving on. You’ll never be there again, at that place, at that time, take advantage of it. That’s my philosophy: photograph your subject to within an inch of its life! And then come back repeatedly until you feel the subject has nothing more to say to you. It’s that commitment, that thoroughness, that helps make strong bodies of work. When it comes down to it, it’s never really my story. I am there to relay a story that has been told to me while living with my subject.

Joe Cornish in a previous article posed the question "Does being an outdoor photographer inevitably lead to environmentalism? And if so, what if anything are our responsibilities?' Does this resonate with you from your experience as a landscape photographer?

I think to a certain extent that is true. Anyone who works in nature, basking in the sheer joy it has to offer, becomes an advocate for its protection. I can't hope to say more than Joe Cornish. He is well versed and eloquent on the topic.

Being an artist has meant not steering my creativity to push an agenda. I think Ansel Adams had his internal turmoil about keeping his motives pure: even after becoming a de facto spokesman for the Sierra Club where he lobbied Congress on environmental matters. In the end, I feel he stayed true to his aesthetics and made work because it was meaningful to him without thought to what anyone else wanted or needed from him. I often photograph things that are not necessarily considered “beautiful” in the conventional sense.

Living in the far north, I am privy to much of the impacts of global climate change. The summers are hotter, winters milder but more erratic. Wildfires burn huge swathes of the tundra, sending all that carbon back into the atmosphere. The melting of the permafrost creates slumps and wetlands that exposes once-frozen middens which encapsulates more than twice the amount of carbon already in circulation in our atmosphere. I try to live a low impact, small carbon footprint, but I admit that it’s a fraction of what is needed. I rely on science to help make good decisions and understand what to lobby for locally and protest for nationally. Any more than that, I fear I am more a part of the problem than the solution. Still, I don’t lose heart. I continue to look around me and document what I see. If my images please people, that's nice. If people are moved to action in the cause of the environment, even better. But ultimately, making art is a selfish endeavour. Its impact, purpose, and ultimate value is left to the ages…. Let’s just hope there are ages to come!

Could you tell us a little about the cameras and lenses you typically take on a trip and how their choice affects your photography?

Since I was a young photographer, I have made sure that my “kit bag” always had the equipment needed to photograph the kind of subjects of interest to me. I always have a wide angle, telephoto and close-up lens. Every camera system I have owned has met that criteria. I tend to like 24mm (full frame format) wide angles. For the last 20-30 years I have used a 24~70, and chose a fast one if I could. I currently use a Canon 24~70 2.8 L, 100~400 4.5, and a 100mm 2.8 macro on a 1Ds mkIII. All that fits into a Think Tank Accelerate camera backpack. That camera has served me well for the last 12 years. It’s getting long-in-the-tooth and it’s time for an upgrade. Recently I have been trying out a Sony A series camera. I’m not super happy with the way it handles, but you can’t complain about the output nor the quality of the lenses. I am also considering the new mirrorless Canon R series of cameras (like the R5). I am not a video person, so my interests are in the still capabilities of a camera.

Surprisingly, when I travel out of state or overseas (all travel is by jet out of Alaska), I only bring a Sony RX100 with me. I admit it is tricked out with all the accessories: clip-on conversion lenses for telephoto, diopters for close-up, polarising and neutral density filters, remote release, etc., all that and my regular full-size tripod. It’s still just a pocket camera, but I am amazed at the quality of its files. It accounts for almost all of my portfolio work when I travel out of state. At exhibition-size prints (usually around 25cm Sq.) I wouldn’t know the difference if I hadn’t made them. Although pushing it a bit, they hold up well when making large-metre-size prints, too.

My work seems to be made most often with a 24mm focal length lens. I like to get up close and see far away at the same time. The trick with a 2 dimensional medium like photography is to give the feel of depth. Using this technique, I get the feeling of depth by exaggerating near to far relationships. It helps to concentrate a viewer’s attention on a subject, but give the image context by showing the environment.

That said, I often like to explore with a medium to telephoto lens that tends to flatten out space. I play with the frame as a 2D design problem to solve. How shapes overlap, or not; how lines weave and draw one’s eye; how colours and tones relate to one another and the emotions they evoke when placed near or far apart.

The old platitude: there is no photograph that can’t be made better by getting closer, often has some merit. But filling the frame with just one subject can lead to a one note melody. I like to tell my students that a photograph is like a play: there is a lead actor, and there are supporting actors, find your lead and position the others accordingly. A single monologue can be compelling, but multiple voices create more interactions and a richer experience. To keep things intelligible though, there needs to be a focus point that everything revolves around.

I embraced the square format when I started using a Hasselblad in the 80s. I feel it is the most interesting format: it is very formal in presentation, it concentrates the viewer’s attention, it’s more interesting to compose in and deal with 2D design issues, and wide-angle pictures are both wide angled vertically and horizontally (bonus!).

My technique with a digital camera is to make two images for each subject: one slightly above and one slightly below the centre of the composition. I later combine the two images in software to get a square format. I do this for two reasons: 1) to increase the resolution of the file, 2) because I’m a square guy and cropping a rectangle goes against my aesthetic disposition (I’m also exceedingly parsimonious. I hate wasting expensive pixels!).

What is your favourite location?

I photograph everywhere I go. Although novelty plays little in my art, I still love to travel and see new places and be inspired by new lands and cultures. Since I don’t travel all the time (or even most of the time), I enjoy working and exploring in deeper nuance the landscapes of Alaska that I have already been to many times before. Once I find something that interests me, I photograph the bejeezus out of it. I come back over and over again looking for a deeper understanding of that place—to find its voice. Even after “finishing” a series, I continue to haunt those locations for years after.

Living in Anchorage must give you access to some pretty fresh seafood?

I visited and photographed in the Monterey, California area for many years. Friends took me to The Fish House one night and I sampled Cioppino for the first time. It's a seafood stew in a spicy tomato base broth, and it is to die for. Being from Alaska where seafood is king, I try and make a big pot of it once or twice a year.

You also studied broadcasting in college. Do you have any favourite films and do you still have a link with the moving image?

I’m a sci-fi nut. Blade Runner has to rate right up there. A lesser known film, Brain Storm, is still one of my favourites. Although I love all cinema, I enjoy the stimulation that it brings to my imagination. Comedy films with social satire run a close second. Dr. Strangelove and This is Spinal Tap are classics.

I have always thought cinematically and intuitively understood the language of film-making, I still watch movies with the eye of a cinematographer and director, but I never embraced the collaborative part of movie making. Still photography has always appealed to my personal aesthetic.