In homage to my great uncle William Wyatt Bagshawe

Peter Cattrell

Glasgow born photographer Peter Cattrell graduated from the London College of Printing in 1982 and has since had various roles in teaching photography and printing alongside his work printing Faye Godwin’s work and latterly her archive. His own work has also been collected and exhibited at many prestigious galleries including the Tate, V&A, Holyrood and the National Galleries of Scotland. His landscape work has been focussed on historical events such as the Great War and the memorials connected with these events.

Charlotte Parkin

Head of Marketing & Sub Editor for On Landscape. Dabble in digital photography, open water swimmer, cooking buff & yogi.

Last year, Peter Jones from the Photo Space got in touch and suggested we talked to Peter Cattrell about his photography project 'Echoes of the Great War'.

In April 2016, Peter's exhibition "Echos of the Great War " opened at Weston Park in Sheffield and marked 100 years since the Battle of the Somme. Peter’s Great Uncle William Wyatt Bagshawe fought and died in the Somme and through retracing the footsteps of his great uncle, he took black and white photographs of the land as it is now, suggesting the terrain of the frontline through details and abstractions.

Can you tell me a little about your background (e.g., education, childhood passions, early exposure to photography, vocation)?

I went to a private boys' school in Edinburgh and was hugely into sport. I was best at subjects like History, English, and Art. I did photography as a hobby at the school's camera club, and they had a darkroom attached to the chemistry department, so did my first processing of films and printing there. I would go to exhibitions in Edinburgh, and with the annual festival, there were always important shows of art and photography such as August Sander, Lewis Hine, Karl Blossfeldt, and Cartier Bresson. I remember seeing the Becher's show of photographs of colliery pit heads in Glasgow in about 1975 and thinking it such a strange idea for an exhibition, whereas now their influence and ideas on 'Typologies' are so well known. The Stills Gallery in Edinburgh was important to me and I saw many good shows there, from Tony Ray Jones, to Paul Strand's Hebridean photographs.

My mother had been to Edinburgh Art College and did still life and landscape painting. I grew up meeting many Scottish artists and was aware of the landscape tradition in Scottish art. My father was a scientist, taught at Edinburgh University and he was very interested in art and took it up in his retirement doing painting classes. A friend of his who was a medical photographer gave me a developing tank and I started processing films and then printing at home with a basic Paterson enlarger. He was supportive of my career although it seemed an unusual choice to him, but I'm pleased he saw some of my early exhibitions. My two sisters are both artists, Louise doing painting and Annie sculpture, who went through Art Colleges in Scotland and in London at the RCA, and they have influenced me in many positive ways.

When I left school, I didn't know what direction to take as a career and went to St Andrews University to study an Arts degree doing English, Modern History, and Art History. This was a pivotal year as I realised, I wanted to do something more practical and creative - much of the creativity there was in music and theatre. I used the darkrooms in the student union and was part of the photographic society. I then took a year out and got a job in the department of the National Museum of Scotland. I worked under a good studio photographer, learnt a great deal, used medium and large format cameras every day, and also did much printing and darkroom work. It was very precise and technically high-quality work. He encouraged me to apply to the London College of Printing and do a degree in Photography.

Tell me about the photographers or artists that inspire you most. What books stimulated your interest in photography and who drove you forward, directly or indirectly, as you developed?

In the early days, I liked Bill Brandt very much and wrote to him when I was a student at LCP. Sadly, he died soon after and I didn't meet him. The 'Shadow of Light' influenced me a lot due to the intensity of the printing and rich moody tonalities. I was given a book on Paul Strand's work which I liked and have been a lifelong fan of his. The TV series 'Exploring Photography' presented by Bryn Campbell was an important influence and introduced me to the work of Faye Godwin, John Blakemore and other well-known contemporaries. I liked Richard Avedon very much and saw a TV documentary on his portraits of his dying father which had a strong effect on me. In 1980 I went to Salford 80 which was a big Photo Festival and enjoyed seeing all the exhibitions. I saw the show 'Mirrors and Windows' of American Photography at the Edinburgh Festival in 1981 and wrote about this in my end of course thesis. The model of American photography being either a window on the world like Robert Frank or a mirror of the photographer's own self such as in Minor White's introspective work was I thought very useful. I remember seeing a big show of Richard Misrach's work at the Photographers' Gallery and being hugely impressed by his large colour prints of jungles at night with flash. I was taught at LCP by Jorge Lewinski who did workshops in portrait photography, and inspired by this I did a series of portraits of artists. As a student, I bought a copy of Robert Frank's Americans for £1 in a street market and this is a prized possession.

Some of the Scottish painters like Sir William Gillies and Joan Eardley are important to me, and the German artists Anselm Keifer and Joseph Beuys fascinate me. In the 1980's I started teaching on workshops at the Photographers' Place in Derbyshire and Paul Hill's ideas influenced me as he used to encourage students to work on areas of landscape that were important or significant to them, and not necessarily dramatic and scenic places. I also went on workshops such as Hamish Fulton, and Platinum Printing with Pradip Malde and Mike Ware. I taught a 'Zone System' workshop with Peter Goldfield many times there, and all of these connections have had a lasting significance. Michael Schmidt's 'Waffenrue' is a favourite book of photographs of Berlin before the wall came down. The Japanese photographer Fukase's book on Ravens is very powerful and a favourite.

Tell me about why you love landscape photography? A little background on what your first artistic passions were.

I spent much time as a child in the country and used to go fishing with my father - I sometimes think that landscape photography is a bit like angling - you can spend a lot of time waiting for a bite and getting to know small stretches of river and coast. After my father died in 1991, I went to a river we had fished in Ayrshire and took some photographs of where he had caught a salmon when I was six years old. I used to watch my mother drawing and painting and she encouraged us to do the same. Living in Glasgow, and then Edinburgh, you were only a short journey to the country and we holidayed in the Scottish countryside, which was very formative. I did a lot of hillwalking and started taking a camera along. My portfolio to get into LCP had many landscape photographs in it and I went through a phase of pushing 400 ISO film to 1600ISO to get grain and mood. I did many portraits also when I started and my degree show had a portfolio of portraits, and abstract urban landscapes shot on 6x6cm. At LCP I was taught by many good visiting tutors such as Homer Sykes, Martin Parr, Brian Griffin, Paul Hill, and more. I did all kinds of projects from reportage, still life, fashion, portraits, and screen-printing. We had a brilliant technician Heino Johansson who ran the darkrooms.

I think landscape work is in your blood or DNA, and it became my main area of work from about 1984. I had a small show of my urban pictures at Lacock Abbey in 1983, then drove around the area and went back to do some more photography which started it off. Simply owning my first car in 1984 helped hugely as I had the freedom to go off and travel more easily and do creative work. I have been researching about the German concept of 'Heimat' or homeland which is nostalgic for rural life and sense of place, but which was distorted by the Nazis for their own extreme ideology. Many people in Europe have a fragmented sense of identity as they live in different locations, and you can trace your ancestry from different countries. Some of the choices of location that I have done have been to do with family history and personal connections.

In an interview with ffoton.wales it states “Highly regarded for his landscape photography made in Britain and Europe, Peter works primarily with film and fine printing techniques - and these skills as a master printer brought him to the attention of the renowned photographer Faye Godwin who worked with Peter to print her black and white landscapes of the British countryside.” Can you tell us about your background in film and printing and more about how you came to print Faye Godwin’s work?

In my second year at LCP, I was taught by Helen McQuillan who ran advanced fine printing workshops. She had worked with Faye Godwin and it was through Helen that I was introduced to Fay when I left college.

She became politically very active and was keen on environmental issues. I started doing rural landscape work as my main creative area, having previously done much urban imagery, and this aligned me more with what Fay was doing. Her retrospective 'Land’ at the Serpentine gallery and the book, in 1986 was a high point, brought her to a much wider audience, and was a big achievement. My generation worked with film because we had no choice, whereas now the emphasis is on digital, and maybe exploring film as a change, or to be alternative. I printed for Fay from 1982 to 1990, did more when she showed at the Barbican in about 2002, her big retrospective, and was printing for her when she died. I have recently done some printing for her archive which is held at the British Library. Occasionally I print for museums which is always interesting when they are old or unusual negatives, and one project I did was printing glass negatives at the IWM darkrooms of women in Scotland working in WW1 doing what had previously been men's jobs. It was Fay who got me involved with teaching as I assisted her on workshops, which led on to Central St Martins asking me in to teach.

Your work is held in numerous collections around the world, including the V&A, London; Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris; National Galleries of Scotland; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Goldman Sachs, London and National Trust for Scotland. Can you tell us how these collections have come about and how you worked with the various museums?

I had a show at the Edinburgh Festival in 1987 and the curator Sarah Stevenson bought a set of prints for the National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh. She was starting to build a collection for the National Galleries of Scotland. Later they would buy other prints and I would also donate work to them. My Scottish roots are very important to me and it is where I have done much of my best work. In 1988 I showed my portfolio to Mark Haworth Booth at the V&A and he bought some prints for the collection. In 1989 I did a trip to the Photography Festival in Arles, showed my portfolio to many people including Jean Claude Lemangy, who gave me a show at the Bibliotheque Nationale in 1993 and bought a set of prints. It is very useful to have work in important collections as curators put on group exhibitions or publish books and include your work. How you publicise yourself in the art world of photography is an issue and people want to know if your work is held in important collections. Meeting curators and keeping them in touch with what you do is important. Going to Photography festivals, and showing your portfolio is something you have to do. I was commissioned by the Scottish National Trust through a design group in Glasgow, I also did a project for the Hunterian Art Gallery in Glasgow, and a favourite project was for the new Scottish Parliament in Holyrood photographing Scotland to make a set of prints for display and their collection. I like it when curators know my work and commission me to do a project, trusting me to do my own interpretation.

You’ve lectured since 1986 at Central St Martins, Camberwell and London College of Communication, has teaching influenced your style and approach to photography?

Teaching has given me less time to do my own work, and it does take up a lot of your energy. I like working with people, so teaching fulfils that side of me as landscape and darkroom work is more solitary. I think when you teach you have to really know your subject. Initially, I taught fine printing and then started teaching other areas such as the 'zone system', studio lighting, medium and large format, colour printing, architectural, portrait photography, and nowadays I have to teach digital and Photoshop. I was taught some critical theory at LCP, and am aware of the balance between teaching technique, and the ideas that underpin what you do in creative practice. There have been many students who have good ideas but need help putting them into practice by understanding technique. Some people have technical ability but their work lacks research and is weak. I think there have been times when too much theory has been taught at the detriment of technique at colleges. Teaching has kept me in touch with contemporary theory and ideas. I think understanding technique or the process of photography, needs to go hand in hand with concepts, theory and ideas and is as important.

When you talk to groups about your own creative work you clarify what you have done and also get feedback on your approach and ideas and placing these into a cultural context is essential in modern practice. At CSM I have worked with degree students who are majoring in painting, sculpture or film, and they approach using photography in a different way to perhaps a photography degree student at LCC. Many students do projects which are issue based or a piece of theory that a tutor has proposed, so you must be open to working with anyone on a variety of projects. I had to do a Post Grad course in reflective teaching for Higher Education which was very interesting as it put an emphasis on how students learn and turned on its head many of the preconceptions you might have about teaching or your own experience of being taught at university in past years. Meeting other tutors who are practising artists in other areas has inspired me. I currently teach a portfolio short course at CSM which covers a wide range of work and projects which I like, and portrait courses. In some ways, I think I keep my creative work separate from my teaching persona, but in some areas, they cross over very much.

In an interview with Museums Sheffield, you say “When I did my degree in Photography at London College of Printing the Falklands War happened, and we discussed that, including how different newspapers used photographs. As a child I remember seeing images of the Vietnam war regularly, and also the troubles in Northern Ireland were very prominent. As a tutor at St Martins, I watched the Gulf, and Afghan wars on TV “How do you think this influenced your focus on the project “Echoes of The Great War?”

Any cultural references influence your thinking and I was impressionable as a child when the Vietnam War images were on the TV news every day and in the newspapers. I remember reading Michael Herr's book 'Dispatches' while at St Andrews. The troubles in Northern Ireland were also in the news each week and felt very close to home. Coverage of war has changed so much. It is interesting to look at Goya's etchings of Disasters of War from the C18th, or Otto Dix's etchings of WW1. I have often visited the Imperial War Museum in London and looked at the painting collection, and have always liked Paul Nash's paintings of conflict, but other artists like Eric Ravilious appeal very much also, and Brandt did much work of bombed London in WW2, and Cecil Beaton did much imagery also.

Memorials are in every village, town and city in Britain so you are reminded of past events everywhere you go. My grandfathers were both in the Great War, one in the Navy in Orkney, and the other in France and Belgium working with artillery. I have several great uncles who fought also in different theatres in WW1 including Italy, and one in the naval Battle of Jutland.

Roger Fenton's photographs of the Crimean War have always struck me due to the empty images of battlefields after the conflict has happened, and Timothy O'Sullivan's work on the American Civil War I have found haunting, as images of strewn bodies lying dead on the field after the battle is over. In Britain, there are traces of military history everywhere, not least the many concrete blocks and empty pillboxes that are still around the coast to prevent invasion, which I have photographed, and some which I played on as a child in East Lothian. I have a fascination with history and Britain is so rich as a subject for study, that can inform creative projects in any medium. As a student, I saw a big show of Don McCullin's work at the V&A and much of that show was striking reportage of conflict and suffering. A theory tutor at LCP brought all the different newspapers one day during the Falklands conflict in 1982 to show how one image of the exploding ship was presented in different papers, to discuss that the context in which an image is used influences its meaning. The live video images of missiles being directed on targets in recent wars in the Middle East is so different to how earlier wars were represented, and we are told of, or shown images of violence and its effects every week in news coverage such as terrorism. My intention with the Great War project was to approach the specific story of my Great Uncle, rather than comment on war as a whole, and I think of it as a loss of a very talented generation on both sides.

You say in an interview "The project Echoes of the Great War is in homage to my great uncle William Wyatt Bagshawe and his friends in the Sheffield Pals. I started by photographing the frontline of the Somme at Serre where they died. Uncle Willie’ was an artist who did mostly landscape subjects, and we have some of his work, including watercolours and etchings". Tell us a bit about the project 'Echoes of the Great War’. Where did it all start and more about your personal interest in this subject?

The research has played a big part in my enjoyment and fascination with the subject. My grandmother had kept an archive of family photographs and letters and she would show them to me as a child. When she died, I took over this archive, and have added to it. There were letters by Willie to his parents from boarding school at Framlingham College in Suffolk, back to Sheffield. He used to draw and doodle on these letters and envelopes which endeared me to him. He studied in Sheffield and then went to the Slade School in London, which became famous afterwards with people like Paul Nash and Stanley Spenser students there, and Henry Tonks teaching. Willie was part of the New English Art Group which was a breakaway group from the Royal Academy school and he did mostly landscape paintings and etchings, as well as funny sketches and cartoons. He will have done many cartoons of friends in army life which must exist somewhere.

My grandmother had several photographs of him with friends at training camps in England, and one in particular of him with three friends is very poignant, sitting on the grass smoking at Cannock Chase. All but one died on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, and those three are on the big arch at Thiepval as part of the 'Missing of the Somme': William Wyatt Bagshawe, Edward Stanley Curwen a classics master at Rotherham Grammar school, and the poet Alexander Robertson from Edinburgh who was a history lecturer at Sheffield University. The survivor 'Mr Bailey' went back to Sheffield University, and I think became a school teacher, and I will look at the census returns from 1921 next year to try and trace his family.

In 1989 I drove down to Arles in the south of France to visit the annual photography festival. After that, I did a three-week trip driving north and visiting places of interest to photograph the landscape. In the last few days, I visited Verdun where the French held back the German advance in WW1 defending a huge fortress which protected Paris. I took some photographs there of shell holes in the forest and was very moved by signs showing where a village had been. This was completely destroyed by shellfire and tape and name tags show where the Marie, the schoolhouse, and the bakery had been.

How did the project evolve? Did you have to refine the vision of what you wanted to achieve when you progressed in researching the project?

Initially, I went to the 80th anniversary commemorations in July 1996 and took some photographs of the frontline where he died. I was there at dawn on the 1st July 1996 - 80 years to the minute and someone blew a whistle at 7.30 am when the main attack started. I spent several days there taking different images and doing some portraits of visitors and reenactors. I was hooked on the area and the feelings I had about the place were very strong. The frontline areas have a presence that is very special. They are now just farmland with a rotation of crops such as sugar beet, corn, and maize, and each time I visit the place looks different. There are several woods on the Somme which if you enter are very atmospheric, but also dangerous with unexploded ordnance - 'Passage Interdit'.

To start with I thought I would probably do one visit just to see the place, but on returning to London and processing the films it became clear that I was getting good images, and made me want to develop the project further. There were other connections to follow such as my father's uncle who had fought through the whole war and won a medal near Ypres; the war poets Sassoon and Owen intrigued me as they had met in South Edinburgh not far from where I had lived, and I had studied their writing. I have taken images of where Owen died, which is also near where Matisse grew up. Other areas of the Somme and Ypres front interested me and I included them in the project. The image of the four men sitting smoking has made me research about them and their backgrounds, as well as where the Sheffield Pals trained and the story of the battalion. I traced and met up with Alexander Robertson's relation in Scotland who talked of him as 'Uncle Alex'. I also discovered that I am related to Charles Hamilton Sorley, another well known poet who died at Loos in 1915, as a relation married his twin brother. He was an influential poet admired by Sassoon, Owen and Graves. I hope to do work at Loos in the future.

In 2019 I visited my old school in Edinburgh and researched in their archive as over 200 former pupils were killed in WW1. Many died at Gallipoli but some were at the Somme and are on the Thiepval memorial for the 'Missing'. I may do some work to include this connection into the project. Similarly, I became fascinated by Colonel McRae’s battalion from Edinburgh based on the Hearts football club and their supporters. I was involved in a charity auction to build a memorial cairn at Contalmaison, where the battalion reached their objectives on the 1st day of the battle. The potential to expand the project is obvious, especially when there is a personal interest, but it is a question of funding and time, as I have done the project self-funded.

Did you plan the images that you wanted to capture or were they more spontaneous when you visited specific locations?

The images were a spontaneous response to the locations, and the hardest part is reading up about each place, and knowing that you are actually at the correct place when you are there as it is all farmland now. Occasionally you come across the remains of concrete bunkers and if you go into the woods you can see the zig-zag of trenches. If you walk the fields you come across lead shrapnel balls that were fired by the British - lethal if the opposition soldiers were out in the open, but not if they were hidden in underground bunkers as at the Somme. For years I photographed at Serre and on the frontline, there were four copses named after Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Matthew doesn't exist anymore, and the others are now one wood. I read that the Sheffield Pals came out of John Copse, and the Accrington Pals came out of Luke Copse, but recently I read that Willie's 'A' company also came out of Luke Copse. He had volunteered to be in the first wave at 7.20 am which was very brave as they had little chance of survival. His group lay down in front of the uncut German wire at 7.20 am and he was shot by a sniper. The main attack started at 7.30 am with the blowing of several large mines under the German front line. So many guidebooks have been written for people walking the frontlines, and there is much tourism with people visiting cemeteries, and coach tours with guides. I have met many people on their own pilgrimage to the sites and doing their own research.

The contemporary images you’ve taken of the location of battlefields which are of the tranquil countryside are a stark contrast to the horrors of the war. What narrative did you want to convey to the viewer when you were making the images?

In a way I wanted to show the ordinariness of the places, and how strange two huge armies could meet in these bits of farmland, and that they should have such huge significance. Some small villages in the Department de La Somme became such famous names in military history such as Serre, Beaumont Hamel, and Thiepval in the same way that people talk of Crecy and Agincourt.

The way I have composed the photographs is often details, and abstractions of parts of the places and this is probably how the foot soldier saw the field ahead. I have not gone for grand views or sunsets with poppies. I have visited many cemeteries and often photographed them but have not included these images when I have exhibited the project.

The memorialisation of the war in stone and sculpture is a separate issue to me and I have read about this including Geoff Dyer's 'Missing of the Somme'. He also did a trip with John Berger which was a BBC radio programme where they discuss the places and the way the war is thought of and remembered. The whole concept of the 'Missing' is fascinating - how do you live with the knowledge that your son or relative is reported as missing, not killed or wounded, and has no known grave. Many waited in hope of news of someone reported 'Missing' only to get confirmation later that they were dead. Willie's mother put an ad in the Sheffield Telegraph asking if anyone knew of what had happened to Willie, and she had a reply in a letter describing his death by someone who was with him. Sadly, many like him lay there in no man's land for months and his body may have been hit by a shell, or deteriorated and unrecognisable, buried as a 'Soldier Known unto God', or 'A Soldier of the Great War'. I may have seen his grave but not known it was him.

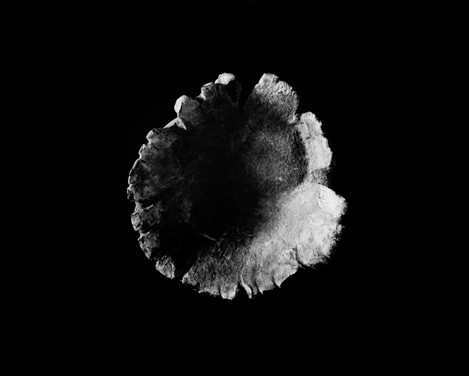

I have been involved in the visitor centre at Thiepval and they have been trying to place faces to the names on the memorial to the missing. I sent in the images of Curwen, Robertson and Bagshawe and they used these in a lightbox collage of many faces as you enter the centre, and on a poster that you can buy. I did a talk at CSM on the project and one tutor was critical of the work saying why was there mostly trees and agriculture and not more evidence of the industrialisation of the war. If you go there, there are traces of shell holes and trenches but very little else. There are a very few concrete structures - the places are tranquil but I think I have tried to capture an edge in the imagery, and also the sense of mystery that I feel there. In a way the absence of traces is the point of the work, hence the title 'Echoes of the Great War', as the work is not a record of the battle, nor an architectural project on memorials and gravestones, but more that there is a regeneration of the places, and the overall terrain is much the same as it always was. To me the land itself is a memorial, as it is where the men fell, many of them particularly the 'Missing' are part of that soil. The architecture of remembrance of the cemeteries and memorials is important too but it is not what I have chosen to present. I collected some shrapnel fragments, bullets, wire, and other debris while walking the frontline, and then did extreme close ups of these pieces which I include in the exhibitions. I was struck by how small these pieces are but how lethal they were in the heat of battle.

“The colour prints taken at Redmires are of the area where the Sheffield Pals camped and trained, and are a new departure working digitally, but in the same contemplative way with a tripod and long exposures, pursuing the highest quality. The winter of 1914 at Redmires was bitterly cold with much snow, and the first casualty in the Pals was someone dying of pneumonia...” Tell us more about the images you took at Redmires Training Camp.

The Sheffield Pals were the 12th Battalion of the Yorks and Lancs Regiment. They recruited many men from the university students and were thought of as a rather middle-class battalion.

They were billeted above Sheffield in the hills near Redmires reservoir where they were trained in shooting and did many route marches to become fit for service, such as to Stanage Edge which I have photographed, and around Stanage Pole, there are carvings of names on rocks by the soldiers. I found one by a Sheffield Pal - 'Alflat' - and I know his grandson who I met at the Weston Park Museum in 2016. There is a forest at Redmires where you can see the concrete bases of huts which were there in 1914, but in WW2 this was a prison camp for German POW's. I have visited several times and photographed in different seasons, once in early 2015 in heavy snow as I wanted to be there at the same time that there had been bad weather in 1915. I like photographing in snow for the graphic qualities you get in black and white but took colour pictures on a digital camera as a change. I have used colour on the Somme to a certain extent but have not exhibited these. I see the series in black and white in my mind's eye, and I like the format of 6x7cm with mostly horizontal pictures. There is a gravity with working in black and white and I think this suits the project, and I am always drawn to the sense of abstraction that B/W has rather than colour.

There was trench digging at Redmires, and I have been to those sites with a historian. A good friend of mine in London has a brother who lives in the same house in Sheffield that my grandfather Benjamin and Willie grew up in on Fulwood Road. This is not far from the gallery and is in an attractive part of the city, a short drive from Redmires. I have stayed with them in the house that my family lived in before WW1 and they have been very supportive to me during this project, and I have photographed the house, although I have not exhibited these pictures. Just before WW1 they moved to Wolstenholme Road not far away, and Willie's older brother lived there until 1956, but this house is now flats. There is a novel 'Covenant of Death' by John Harris about the Sheffield Pals, which is based on interviews he did with survivors at the reunion dinners in the 1920s. He calls the camp 'Blackmires' in the novel and goes into details of the training and life there and follows the story of their journey through different training camps at Ripon, Cannock Chase, Salisbury Plain, then to defend the Suez Canal against the Turks, and finally across to France for the 'Big Push'. He described them as 'two years in the making and one day in the destroying'. A recent book 'The Meakin Diaries' of another Sheffield Pal describes how he was in a later wave at Serre, and ran past Uncle Willie lying dead there in the first wave, and jumped into a shell hole for cover, after which he crawled back to the British line under cover of darkness. The attack was a failure and didn't reach its objectives as the German trenches and wire had not been destroyed by the 5 days of shelling leading up to 1st July, and they came out of their deep shelters to set up machine guns at a terrible cost to these Pals battalions. The 'Somme' is often used as a metaphor for disaster and the loss of life in a short time - the first hour of the attack was dreadful, with wave after wave leaving the trenches and walking uphill into the machine gun fire, as the generals had expected there to be no opposition as the German front line had been shelled so much.

You had an exhibition in April 2016 to mark the 100 years since the Battle of the Somme at Weston Park, Sheffield. How did this come about? How did you go about planning the exhibition and alongside archival materials including artwork, letters and maps?

I first showed the project in 2000 in Dublin, and then Belfast in a group show 'For Evermore', then in Edinburgh at the National Portrait Gallery in 2005, followed by the Durham Light Infantry museum, and the IWM in London. I didn't show it for a while after that as I was doing other projects, but kept doing bits of work when I could, often on family holidays with children. The 100th anniversary inspired me to show the work again and I showed it in London in 2014 at the Robert Fleming Gallery, and in a group show at the National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh in 2015. I contacted the Sheffield Museums as I had always wanted to show the project there. They were keen on the idea and put it on at the Weston Park Museum in 2016 to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the Battle of the Somme. I was so pleased to show there and they included many artefacts from private collections and their own archives to add to the exhibition. I had my file of letters, and vintage photographs, and Willie's paintings and drawings, and this was added to by the museum but also the University which is nearby. Outside the museum is the sculpture of a WW1 soldier and is the city's memorial to the Pals. I have also seen the chapel of remembrance in Sheffield Cathedral and Willie's name in the book there, as are his friends Robertson and Curwen and the other fallen.

Tell me what your favourite two or three photographs from the series are and a little bit about them (please include these images in the ones you send over)

The Maize Cutting at Serre 1997

This is taken looking uphill towards the German front line, and the farmers were cutting the maize crop that day and I liked the angle and line of the maize. It is metaphorical of the cutting down of the crop which is symbolic of the scything of the men as they walked uphill, heavily laden with backpacks and tools, into the machine gun fire at short range that could tear them apart.

Avenue of Trees at Newfoundland Park 2000

This is taken on a very cold misty day in January, after a storm so one of the branches had fallen down. The Park is often visited by coaches of people during the summer months and students show visitors around. The trenches have been preserved and the Germans held a strong base called 'Y Ravine' which was captured by a Scottish regiment later, so there is a huge memorial of a kilted Scots soldier.

Could you tell us a little about the cameras and lenses you typically take on a trip and how they affect your photography?

For this project I have taken mostly a Mamya RZ67 with a series of lenses: 50mm, 65mm, 90mm, 127mm and 250mm. You get fantastic quality from these prime lenses and the camera on a tripod, with 100 iso film. I have taken a digital camera and taken colour pictures as well - a Nikon D810 with different lenses.

What sort of work do you undertake on your images? Give me an idea of the processes involved.

With film I use the zone system carefully and process the films at home in my darkroom, using different dilutions of developer and times than the norm. I do contact sheets, and proof prints at about 10x8, then do exhibition prints on silver gelatin paper. The whole process is quite slow and takes time to digest which I like. I have shot several colour negative films which get processed in C41 in a lab and may be scanned or printed in a darkroom, or digital as Giclee prints. With digital, I shoot RAW and put them in Lightroom, but edit in Photoshop. I don't do much post processing apart from small changes to get the colour balance, or exposure correct. I print on archival paper and use archival inks.