Toward subjective expression and away from objective realism

Photography’s potential as a great image-maker and communicator is really no different from the same potential in the best poetry where familiar, everyday words, placed within a special context, can soar above the intellect and touch subtle reality in a unique way. ~ Paul Caponigro

It’s interesting how often artists, including photographers, refer to poetry when describing their work and philosophy. The correlation is easy to understand when considering that the word “poetry” derives from a Greek word meaning to create or to bring something into being. This definition is close to that of the word “art,” derived from a Latin word referring also to items brought into being by human skill.

The distinction between prose and poetry in writing is analogous to the distinction between representation and artistic expression in photography. In both cases, the difference comes down to how one expresses meaning: literally or metaphorically, objectively or subjectively, decisively or ambiguously, descriptively or implicitly.

One glaring difference between writing and photography, however, is this: in writing, neither poets nor journalists try to assert their own style as the only valid form of writing or to demonise others. In photography, expressing meaning poetically, departing from objective representation when it serves no useful purpose or even distracts, is still often met with ire. In writing, no journalist is concerned that the existence of poetry may diminish the importance or credulity of reportage, and no poet worries about readers feeling deceived if they realise that poetic verses are often not meant as statements of fact. In this sense, the analogy also makes it plain how far photography still has to go as an art form, if only just to catch up to where other media already are.

Pondering the challenge facing photographers aspiring to creative expression, W. Eugene Smith wrote, “I am constantly torn between the attitude of the conscientious journalist who is a recorder and interpreter of the facts and of the creative artist who often is necessarily at poetic odds with the literal facts.”

I find it unfortunate that any photographer would feel torn between these two intents as both are squarely within the capacities of photography and only in contention because of misinformed assumptions about non-existent limitations inherent in the medium. There is no practical reason—not even in terms of photographic purity, however one chooses to define it—why photographs can’t serve both purposes without diminishing either.

Among other photographers who pondered photography as it relates to poetry, Minor White (who was a poet as well as a photographer) wrote: “My pity for the pure photographer / My pity for the pure poet / Is tempered by the responsibility / I have to three media / Whereas they to only one.” Ernst Haas, former president of Magnum Photos, wrote, “we are on the way to speaking our very own language. With it we will have to create our own literature. You will have to decide for yourself what kind of works you want to create. Reports of facts, essays, poems—do you want to speak or to sing?”. Henri Cartier-Bresson wrote, “I’m not responsible for my photographs. Photography is not documentary, but intuition, a poetic experience.”

Despite such historical figures acknowledging the artistic potential of photography, many photographers today still wish to clip photography’s expressive wings: to renounce its ability to serve as a medium for visual poetry, distinct from but equal in importance to its ability to serve as a medium for factual representation. This is not to say that a photograph can’t be both factually representational and poetic in meaning, only that there is no tenable argument why the former should be a requirement for the latter.

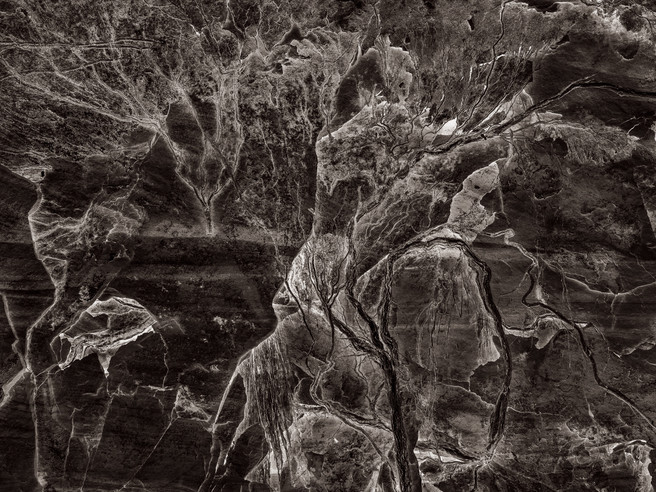

Perhaps a stronger argument in favour of acceptance of photography as a means for (metaphorical, non-representational) creative expression is that, regardless of opinion, poetic photographs—many decidedly not representational—already make a great proportion of photographs one is likely to see in public media. This accords with the general trend in art—away from literal representation and toward greater abstraction, subjectivity, symbolism, and ambiguity.

In considering artistic movements of the past, it takes little knowledge of art history to distinguish based on appearance alone between a realistic painting and an impressionistic one. But art has long moved past impressionism, too. Much of today’s art, loosely referred to as “post-modern,” is no longer about any adherence to recognisable styles or purity of process, and more about the expression of ideas, by whatever means the artist sees fit. It’s inevitable that photography practised as art will follow the same trajectory. (If anything, it’s about time photography stopped playing catch-up with other arts.) Those who tried to derail such progression in other media have often found themselves on what we now consider “the wrong side of history.”

On a recent On Landscape podcast discussing truth to nature David Ward commented, “nobody gives any objection at all to the fact that paintings aren’t real.” This may seem obvious to us today, but it was not always the case. Until the late 19th century, fidelity to nature was considered in many venues (notably in France, which was the hub of western art at the time) as the highest aspiration for art. Works that departed from realistic appearances, such as those by the early impressionists, were shunned, sometimes even ridiculed, and excluded from the most prestigious exhibitions, such as the Paris Salon.

The invention of photography, portending a future in which the photographic medium could surpass painting in its ability to portray natural, realistic appearances, was seen by some critics as potentially ruinous to art. Charles Baudelaire, a distinguished poet and art critic, wrote a scathing rebuke of photography in an essay about the Paris Salon of 1859—just three decades after the invention of photography. In his critique, Baudelaire wrote this:

“In matters of painting and sculpture, the present-day Credo of the sophisticated, above all in France (and I do not think that anyone at all would dare to state the contrary), is this: ‘I believe in Nature, and I believe only in Nature (there are good reasons for that). I believe that Art is, and cannot be other than, the exact reproduction of Nature […] Thus an industry that could give us a result identical to Nature would be the absolute of Art.’ A revengeful God has given ear to the prayers of this multitude. Daguerre was his Messiah. And now the faithful says to himself: ‘Since photography gives us every guarantee of exactitude that we could desire (they really believe that, the mad fools!), then photography and Art are the same thing’ […] this industry [photography], by invading the territories of art, has become art’s most mortal enemy.”

The infamous satirical critic Louis Leroy, upon seeing Claude Monet’s painting, “Impression, soleil levant” (Impression, Sunrise), commented, “I was just telling myself that, since I was impressed, there had to be some impression in it ... and what freedom, what ease of workmanship! Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape.” Prompted by this critique, the early impressionists adopted the term “impressionism” for their movement, rendering Leroy a historic laughingstock. France’s Académie des Beaux-Arts attempted to squelch impressionism by excluding impressionist work from its Salon. In response, the early impressionists started a salon of their own, and prompted a revolution in the arts. As painter Robert Henri put it, “History proves that juries in art have been generally wrong.”

I mention the impressionists not only as an example of art evolving by revolutionary leaps (rather than gradual transitions)—toward subjective expression and away from objective realism. Impressionism holds another important (if not as widely acknowledged) lesson that is eminently relevant to photographers who care about fidelity to real experiences (which, in the case of poetic expression, does not necessarily imply fidelity to real appearances).

Monet famously credited the success of his works to the emotions he felt when working while out in nature, rather than to his distinctive style. Many other impressionists, despite lumping their work into the same category as Monet’s, produced works of similar effect but without the experience of working in, and from, nature. As Monet himself put it, “My only merit lies in having painted directly in front of nature, seeking to render my impressions of the most fleeting effects, and I still very much regret having caused the naming of a group whose majority had nothing impressionist about it.” This should serve as a warning to those interested in poetic expression in photography. Stylistic departures from realistic appearances are not enough (indeed, it’s not even required) for an image to be poetic, but fidelity to true experience is required if one aspires to live a poetic life.

Of those concerned with truthfulness in photography, I ask this: if you inspire in your viewers an experience you did not actually have, is the fact that your images are not “manipulated” sufficient to make them “true”? Conversely, is a photograph that is “manipulated” as to expresses true qualities of experience any less “truthful” just because it is at “poetic odds” with objective representation?