A willingness to happily embrace opportunism

Kathleen Pickard

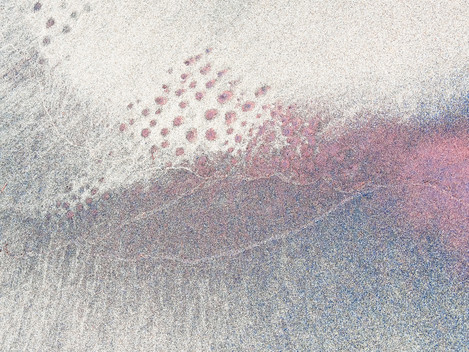

One of my greatest pleasures in photography is uncovering the unfamiliar in the familiar. When I hear from a viewer that “I live here but I’ve never noticed that before!”, I smile in satisfaction. Beauty is often hiding in plain sight, but it takes practice to see it.

It’s no secret that 2020 was a very challenging year to be a landscape photographer; and, with Covid-19 still on the rampage, the prospects for 2021 don’t seem to promise much more. Perhaps it is the limitations on travel imposed by the virus that partly explains why I’ve been noticing that the “intimate landscape”, as a genre, has been receiving considerably more attention than it usually does from photographic communicators.

Too often the message is “since I can’t go to (fill in the exotic blank) I will concentrate more on the details in my local patch”.

The sigh, though inaudible, is implicit.

As a photographer who has preferred to photograph smallscapes for a very long time, I’d like to reassure photographers of the grand vista that that sigh is totally unwarranted. Slowing down and becoming intimate with your home turf may not be as adrenalin-inducing as visiting foreign locales, or garner as many likes on social media, but it does offer different challenges and other rewards.

I define “intimate landscape” very loosely. It’s not as big as the grand vista and it’s not so small that a macro lens is required. You might call it a Goldilocks landscape. It can be found anywhere, even in your backyard, but is often easily overlooked.

To me, the biggest challenge in photographing the intimate landscape is simply being able to recognise your subject. To do that requires two things: the ability to see, really see, and a willingness to happily embrace opportunism.

I happen to live in a geographic area that will never be found on anyone’s top ten list of photo destinations. I’ve even heard it said by some photographers that there is nothing to photograph here in Southwestern Ontario. They’re wrong about that, of course. When in an environment we know well we cease to take in the details of our surroundings beyond assigning them a generalised label in our mind, and then moving our attention on. Think of how we stop seeing our art until we hang it on a different wall.

“Seeing” what is there, as opposed to looking at it, is an active skill that demands cultivation. It takes practice to break down our immunity to the familiar. Successfully arriving at what Freeman Patterson, the noted Canadian photographer, calls a state of “relaxed attentiveness” can be a challenge and I would highly recommend his book, “Photography and the Art of Seeing” as a helpful guide to finding your way there.

An auditory example may make the concept somewhat clearer. When taking a walk in the woods, you may notice birdsong as a background accompaniment, a pleasant noise really; but, if you have developed birding skills when you listen attentively you’re able to identify individual species by their call. The walk immediately becomes a more specific and informed experience. Instead of “birds” you’ve heard a Wood Thrush and a Scarlet Tanager and you’re in a deciduous forest of Eastern North America. The sound is there for all to hear, but educated listening enriches your personal experience of it.

In a parallel way, learning to see attentively will have the effect of enlarging and enriching your world without the need to buy a ticket.

With a fine-tuned ability to see, photographic opportunities will inevitably increase; but that will be of small value unless there is a willingness to receive them with an open mind. It’s perfectly fine to have a goal in mind when going out with your camera, but it’s also important not to have your expectations blind you to what else is there. I’ve often been known to mutter unflattering words at on-screen photographers who have deemed their day’s efforts a failure because the weather conditions haven’t been what they had in mind while walking by endless possible subjects. If it means that you upend your plan to photograph in the woods and go to the beach instead, or even get no further from your car than the parking lot, so be it. What is important is having the flexibility to view unexpected opportunity as an advantage.

Photographing the intimate landscape requires studying the principles of visual design and learning how to apply them to your image in a way that differs somewhat from the grand landscape. Eliot Porter, whose exhibition “Intimate Landscapes” was the first solo show of colour photography at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, explained it this way.

“Photography of nature tends to be either centripetal or centrifugal. In the former, all elements of the picture converge toward a central point of interest, to which the eye is repeatedly drawn. The centrifugal photograph is a more lively composition, in which the eye is led to the corners and edges of the picture: the observer is thereby forced to consider what the photographer excluded in their selection.”

That is, when a photographer wants to share their awe at the mountainscape before them there is no ambiguity about who the star of the show is. Lighting conditions and supporting elements are all chosen to enhance the mountain’s leading role. There is no question about what we, as viewer, are meant to look at.

In an intimate landscape, more ambiguity exists. The photographer has more scope for personal expression and has chosen to select a small piece of the scene in front of them and exclude the rest. Why? What? And what else? These are all possible questions in the viewer’s mind. Rather than being presented with one easily identified subject, the viewer is led through and around the picture space by means of visual design. Whether the image “succeeds” or not ultimately lies in its ability to engage the viewer visually and imaginatively.

Personally, I find great gratification in photographing what others may view as unphotographable - in the sense of “Why bother?” Teasing out a small piece of visual order in a larger scene of chaos or making visible a detail that would otherwise go unnoticed is a quest I never tire of. My ultimate compliment was when I was told that I can photograph “nothing” and make it look good.

So I’d like to reassure grounded landscape photographers that they do not have to put photography on hold until the plague has passed. The Intimate Landscape contains a large world. There is never nothing to photograph.

Acknowledgements

I know that I’m preaching to the choir on the merits of the Intimate Landscape to a significant number of On Landscape’s readership. I can’t imagine that any are unfamiliar with the superb work of David Ward in that genre.

A less familiar name to some would be Krista McCuish, a fine photographer from Nova Scotia. She was a featured photographer in On Landscape in Issue 171.

I also can’t fail to mention the work of my photographic and life partner, Larry Monczka, whose work can be found, along with mine.