Book review

In 1981, a 23-year old photographer happened across a book in his local library. It was, In the Throne Room of the Mountain Gods, by Galen Rowell. Documenting the 1975 American expedition to climb K2, the world’s second highest mountain, Rowell’s pictures dramatically illustrate the barely imaginable reality of the Karakoram. Located in a remote corner of Asia, where Pakistan, India, China and Afghanistan defend disputed borders, The Karakoram region remains little populated, and visitors are limited to elite rock climbers and mountaineers.

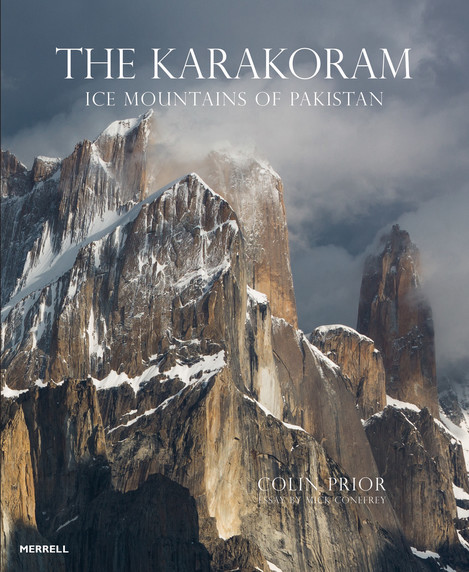

The young photographer was Colin Prior, and his new book, The Karakoram, is the culmination of a lifelong obsession sparked by that discovery in the library.

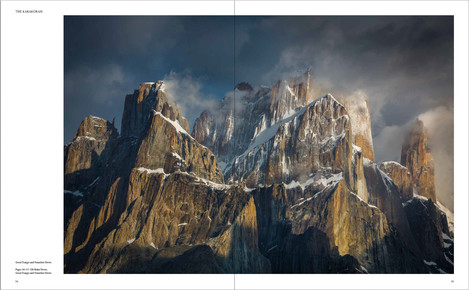

In particular, it was Rowell’s photograph of the Trango Towers that commandeered Colin’s imagination and drove him to visit and photograph the region, not just once, but on six different expeditions.

Fifteen years passed before the first of these adventures in 1996 when Colin was working on a British Airways commission. It was these commissions that launched his reputation as the panoramic mountain photographer par excellence. He returned to the Karakoram in 2004, 2013, 2014, 2015, and finally in 2019.

Any expedition to the mountain regions of Pakistan is fraught with risk. The mountaineering hazards are abundant, complicated by the demands of altitude that can affect judgment, health and sleep. In addition, there are rockfalls, avalanches, concealed crevasses on snow-covered glaciers, unpredictable and extreme weather. These and other hazards are all present just passing through such terrain, let alone when the climber/photographer needs to gain or lose elevation, and deploy many kilograms of sensitive and expensive camera gear.

Any adventurous traveller in Pakistan must also understand its political instability and the risk of ambush, robbery, kidnap… or worse… en route to or from the area.

For Colin, the rewards of facing these dangers was the chance to bear witness to the most dramatic mountain landscape on earth. Although he enjoyed some sponsorship on later expeditions, for most of the time he worked with no publishing contract, with no final outcome confirmed. Towards the end, the Pakistani High Commissioner played a key role in helping ensure the book was printed. But even so, Colin’s personal investment and commitment to fulfilling this huge task cannot be overstated.

And the good news is that all that risk, danger to life and limb, travel and trekking time, and months living in the extreme discomfort of altitude, in a tent, deprived of home comfort…all of this has paid off spectacularly.

The format is great; at 35cm x 29cm it is big, as befits a book of epic mountains, but not too big. And at 160 pages of high quality paper it is not awkwardly heavy, or cumbersome to hold in the hand. The design (in collaboration with Colin’s son Laurence) is beautiful with ample white space, and perfectly-judged proportions.

There is an excellent introduction by the photographer, and then six relatively brief reports on each of the expeditions. They are made through the (metaphorical) lens of a working photographer, and so are really insightful for On Landscape readers and others interested in the photographic perspective.

But they are more than that, for in its calm, restrained prose they convey with real eloquence the depth and experience of someone who has lived with the reality of the mountains around him. He focuses on the facts of light, on the vital role of his guides and porters who have done so much to make these expeditions possible, and there are vignettes of the small details of the environment, as well as the sublime beauty of the region’s great rock cathedrals.

The writing certainly sets the tone, yet it is the photographs that are the purpose of this book, and it is in the beauty and layered visual complexity of the photographs where most of us will dwell, as we turn the pages, slowly. There are three main Muztagh groups of images, organised geographically, which may be helpful for those who know the region. But this layout is a subtle structural detail only because the landscapes are all so uniformly spectacular.

Even though the theme is completely unified there are still numerous creative and artistic decisions that must be made about the pictures, layout, and sequence. Not the least is whether to ‘make’ the picture as colour, or black and white in the age of the digital raw file. Inspired by Vittorio Sella, whose pioneering work from the Karakoram is the first meaningful artistic photography done here, it might have been tempting to stay with black and white.

In fact, the book is a mix of black and white and colour. The purpose of the monochrome images is well-realised, emphasising texture, light, and the sculptural presence of the mountains. Colour brings a vivid depth and reality to these landscapes, emphasising mood and atmosphere, prompting different emotions.

I know Colin well enough to have followed the genesis of this project through the last fifteen years. The digital revolution had just begun when he made the first of these journeys. At that time Colin was shooting mainly panoramic images on Fuji transparency film. Subsequent years brought the full tsunami of multiple digital revolutions: the internet and digital dissemination of photographs; digital capture; digital post production; social media; artificial intelligence.

- © Colin Prior

- © Colin Prior

And so, as we leaf our way through The Karakoram, we are also digesting an artistic obsession that has bridged the analog and digital worlds.

I admit to being nervous of what this might have meant for the book. From my own experience, I know how tricky it was to cross this river, to relearn with the new, imperfect and rapidly changing technology of digital. And especially to combine images made on large and medium format film cameras in the early years, with ones made on smaller digital cameras in the later ones.

The digital cameras have come and gone at a dizzying pace, and there has been the overwhelming realisation that composing the picture alone is not enough. Once we would just shoot the transparency, and everything else would be taken care of by an expert print technician. Now we must also translate the raw image file ourselves, and edit for output, especially print.

Yet somehow, the viewer of this book is completely untroubled by these momentous background events. Can we tell what camera technology was used for a particular picture? No. There is a stylistic and aesthetic coherence throughout. That does enormous credit to the photographer’s consistency and clarity of vision. A deep commitment to synthesising the real, and the imagined is fully achieved. He even makes it look effortless, but the reality behind that effortless fulfilment could not be more different.

Technique is the last thing that comes to mind as we absorb the complex tapestry of these terrestrial monuments, but the fine detail and exquisite tonal rendering of the mountain landscape is the result of superb and consistent technique, whatever camera was used at the time. The film cameras get a mention in the backstory, and if like me you are always curious about the process, you might find the absence of detail about the digital ones frustrating. But ultimately knowing something about the cameras used is pretty irrelevant compared with what was done with them.

These mountains are some of the most geologically fascinating zones on earth. But this is not a geography/geology book, and the photographer has avoided including a geological essay or article to it. Neither is there a history of this critical borderline on the Asian continent, never far from turmoil today. And finally, there is also no mention of the burning issues of our time, climate change and habitat destruction which affects all regions but especially those where ice and snow play such a major role.

The decision to sidestep these questions in the text and narrative is debatable. It means that the book has a certain timeless aspect, and arguably it keeps the reader’s focus on the mountains themselves and the photographer’s experience there. Given the environmental changes that may come, these pictures do undoubtedly represent a time capsule, and will be a geographic reference (as well as a photographic benchmark) for generations to come.

But there is an essay by Mick Conefrey that adds some insight into the photographic history of the Karakoram. What emerges is the surprising fact that before Colin Prior only Jules Jacot-Guillarmod in 1902, Vittorio Sella in 1909, and Galen Rowell in 1975 had done significantly creative work here. Referring to Colin Prior’s The Karakoram, Conefrey’s essay ends with the following sentence: “Anyone who has travelled in the region will be instantly transported back; anyone who has never been there will be booking a ticket for the next plane.” The first half of the sentence may be indisputable, but the second half most definitely is (disputable). Coronavirus and current restrictions on air travel notwithstanding, Conefrey undersells the pictures if he implies they are an incentive for the rest of us to go there as well (although perhaps that is an understandable conclusion in the age of Instagram).

On the contrary, why rush off to see or photograph these sublime mountains? For what would be the point? The pictures in this book stand as an ecological alternative to the hazard and hardship of seeing the real thing. Leafing through these pages makes far more sense than plotting a trip to the Baltoro Glacier, and five or six weeks living out of a high altitude tent.

In every critical respect, The Karakoram is a phenomenal achievement. The mountains themselves are an endlessly absorbing wonder of snow, ice, rock detail, changing light, mood and colour. Yet I know – we all know – that simply pitching up with a camera doesn’t make the mountains come to life. That requires huge commitment, technical expertise, artistic vision, dogged determination…and keeping the faith with a young man who picked up that book in his local library and absorbed these mountains into his soul.

This book and these photographs truly are the summits of Colin Prior’s lifelong journey of the imagination. Although it has taken more than 100 years, finally, Vittorio Sella’s baton has been well and truly passed on to Colin Prior.

Highly Recommended.

The Karakoram: Ice Mountains of Pakistan by Colin Prior with an essay by Mick Conefrey, £50 Merrell Publishers. We always encourage people to support their local bookshops where possible.

- © Colin Prior

- © Colin Prior

- © Colin Prior

- © Colin Prior

- © Colin Prior