What Neuroscience tells us about creativity

Nick Becker

Nick Becker is a nature photographer and outdoor enthusiast based in St. Louis, Missouri.

The Process of Creativity

I loved all things creative as a child. Whether I was drawing pictures of whales and ocean scenes or writing fantastical stories about wizards and werewolves, I was always able to entertain myself with the wild musings of my imagination.

As an adult, I envy the abundance of imaginative ideas I had when I was a kid, outlandish and immature as most of them certainly were. Nowadays, a day job and other personal responsibilities demand attention, often leaving little mental energy for creative pursuits, even when I make the time for them. As a result, sometimes it feels like I am stuck in a creative rut — a feeling that I know many artists are familiar with.

Unfortunately, I have not discovered a simple, easy solution for becoming creatively unstuck. Over time, however, as I’m sure many others have done, I have come to realise that some strategies are more effective than others. As a former student of cognitive science, I was primed to ask myself: why is this? I dug into the literature from psychology and neuroscience, believing that a better understanding of how creativity unfolds in our brains might help shed light on this question, and maybe even illuminate ways to improve my strategies for breaking loose when I am creatively stuck.

My findings confirmed what I already knew: brains are complicated.

I won’t dwell on the details, but at a very high level, creativity is a process that involves the sophisticated interplay of two mechanisms: idea generation and idea evaluation. Normally, the brain networks that support these mechanisms are complementary in that when one activates, the other tends to deactivate, and vice versa. However, neuroscientists have observed increased communication among the regions associated with these networks when research participants are engaged in creative tasks, suggesting that creativity may arise as a result of employing these networks in a cooperative manner. Thus, we can think of creativity as the result of these two processes working together in harmony: spontaneous generation of ideas in conjunction with the critical evaluation of those ideas.

With this model of creativity in mind, I have found that thinking about which process is faltering, idea generation or idea evaluation, can help explain why some strategies for dealing with creative ruts are more effective than others. It has also helped me formulate new ways to improve upon those strategies in the future.

Jumpstarting the Idea Generator

The first process involved in creativity, idea generation, is related to the ability to come up with new ideas, something that I was incapable of doing during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, despite my desire and repeated attempts to do so.

By now, we are painfully familiar with the changes to our lives brought about by the pandemic.

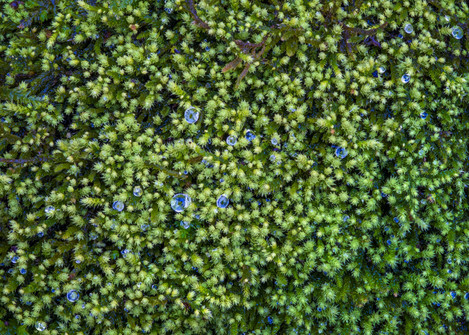

When an afternoon rain left the backyard foliage fresh and sparkling one day, I decided to embrace the symbolism by wandering out once more. I affixed my little 60 millimetre macro lens to my camera and decided in advance that I wouldn’t even attempt to create anything worth keeping. My goal was far more humble: to open up the aperture on my lens and practise manually focusing with a shallow depth of field and no tripod. I knew that the lingering droplets would serve as excellent targets for this exercise.

I began playfully exploring among the various grasses in my backyard, searching for sparkling beads of water. Upon finding a good candidate, I would peer through the viewfinder, get as close as possible, and hold as steady as I could while I quickly adjusted the focus and made the shot without dwelling on composition or technicalities. Then it was on to the next glimmer that caught my eye.

Shifting my mindset away from the pressure to be creative lowered the mental barriers that had been in my way. Without the internal pressure to produce something, my anxieties were able to take a backseat to my imagination, and before I knew it, I was finding ways to put to pixels the feelings of bleak isolation I had been experiencing.

So how was I able to go from uninspired doom and gloom to motivated resolve? In a way, by tricking myself into generating new ideas. Preoccupation and worry had been consuming my mind, leaving me unmotivated and creatively empty. By embracing a different set of restrictions than I was facing in the outside world — namely, limiting myself to my backyard, using a single prime lens, manually focusing, and shooting without a tripod — I was able to reframe the challenge I was facing: my goal was not to create something original, but simply to make images of dewdrops that were in perfect focus within this set of constraints. It was a modest goal, but one that had the ultimate effect of allowing me to get out of my own way, to explore new ideas by indulging in my curiosities and finding a way to express how I was feeling through them.

Evaluating Ideas on My Own Terms

The second process involved in creativity, idea evaluation, has to do with our ability to identify and advance ideas that have potential, and recognising when an idea is not worth additional mental energy. For me, this process is often tied closely to self-doubt. When I am unable to create something that I believe is representative of my artistic vision, preferences, or capabilities, I characterise the problem as one impacting idea evaluation.

This kind of creative obstacle can be insidious, creeping into our artistic faculties so quietly, so gradually, that it isn’t immediately recognised. And in my experience, idea evaluation is particularly susceptible to external factors like the influence of social media, corrupting our self-expression and leading many photographers, especially newcomers, to doubt their work.

I myself have gone through this, and unsurprisingly, in my early days on social media, I found that my desire for acceptance and affirmation on the platform was detrimental to my art. I was creating for algorithms rather than for myself. If an image didn’t “perform” on social media, I thought of it as a failure, which in turn made me hesitant to share images that were actually meaningful to me. If one of those images didn’t garner enough likes, how would that reflect on me as an artist?

Of course, I wasn’t consciously aware of the trap I had fallen into. And even when I began to see social media for the game that it is, I still found myself hesitant to pursue my own creative path and create work that had meaning to me. If I didn’t believe that an image would do well on social media, I hesitated to even create it. Social media had left a mark on the way I evaluated my own ideas.

Looking back, I can now recognise that I wasn’t evaluating my work on my own terms, but rather, trying to cater to the nebulous preferences of the masses and obscure algorithms. These considerations were distracting from my own intuitions, cluttering my mind and making the idea evaluation phase of the creative process even more difficult. The noise was drowning out the signal of my own voice.

By slowly shifting my attention away from the performance of my work and learning to focus instead on the social aspect of social media — using it to build community and forge new connections with other artists — I was finally able to grant myself the permission I needed to embrace and pursue my own vision. I learned how to be honest with myself when I wasn’t evaluating my work on my own terms and started relying more and more on my own instincts as an artist. While it’s not always easy, I now try to focus on creating for myself, something that I am fortunate enough to have the luxury of doing.

Rediscovering Your Inner Child

So why do certain strategies for overcoming creative ruts work better than others? I’m not sure I’ve provided the answer here, but maybe I have at least started the right conversation.

If science is clear about one thing, it’s that there’s probably not a simple way to rediscover the unbridled imagination that we had when we were children. Even under ideal circumstances, being creative is challenging. Internal and external factors in our busy, stressful adult lives can make it even harder, creating obstacles to creativity that feel impossible to overcome.

But my hope is that the examples provided in this article illustrate how thinking of creativity as a process of idea generation and evaluation might help to form a framework for overcoming future obstacles to creativity.