Part 2

David Ward

T-shirt winning landscape photographer, one time carpenter, full-time workshop leader and occasional author who does all his own decorating.

To know fully even one field or one land is a lifetime’s experience. In the world of poetic experience it is depth not width that counts. Nan Shepherd

It is common in modern societies to order our days according to a set of deadlines or goals. We make lists; we write in calendars; we strive to break the monthly sales target; we ask ourselves where we want to “be” in five years’ time, and how we will actually achieve our appointment as V.P. (or living off-grid in Alaska). Even leisure, our “off” time, is directed according to targets. We want to get to fifty sit-ups, we want to go from couch potato to running 5km, we want to walk the El Camino de Santiago, we want to get to the summit of every Munro in Scotland, and we want to get drunk in Harry’s Bar.

Of course, human ambition is nothing new. And targets give us something to aim for. In a sense, they simplify messy reality. Once we have reached a target we can cross it off our list and move on to the next. But I think we are often guilty of aiming for the obvious target, our eyes forever on the grand prize. It’s tempting to head for the mountain’s summit, sheer scale makes it stand out more than anything else. But maybe what we need to learn is closer to home. In the words of David Thoreau, “Many men go fishing all of their lives without knowing that it is not fish they are after.” An attractive activity can obscure our real needs. So, rather than heading for the hills, we might more productively spend our time really looking, perhaps for the first time, at what lies in our backyard.

As an aside, twenty years of teaching photography has shown me that prescribed targets are largely irrelevant. Sure, you can cross items off a list of technical aims. But being able to produce a perfectly exposed, perfectly sharp image doesn’t make you a photographer, just a competent camera operator. To learn how to be a photographer you need to learn a different way of thinking in conjunction with ways of doing. You’d never know it from reading most articles on photography but “why?” is way more important than “how?”

Where was I? Oh, yes…

In part one of this article, I promised to tell you how to make your images “outstanding”. What did I mean by that? I obviously didn’t mean images with the most hearts or likes next to them.

As I hope I showed in part one, chasing the approval of your peers (on FB, Instagram, 500PX, Twitter or whichever your chosen channel for mainlining dopamine) will not make your mages original. Popularity is more often than not a normative force, nudging creative output towards the middle-of-the-road. That way lie “The Osmonds” or “The Bay City Rollers” or yet another photo of that bloody tree near Queenstown, NZ!

Albeit addictive, aiming for likes is a fool’s errand.

Likes are undeniably tempting because they are quantifiable. Their externality can easily be mistaken for an objective yardstick to one’s photographic ability. But that is just an illusion. One hundred likes, a thousand likes or even a million likes do not necessarily mean that a photograph is good. They don’t even necessarily mean that the image itself is popular. Looking at images made by celebrities, it’s obvious that it’s the poster who is well-liked. There is simply no direct correlation between creativity and popularity.

Sadly, as social animals, we so often see ourselves in relation to others that it can be hard to recognise our own worth. We never seem to be able to truly satiate our hunger for external praise. Of course, when it comes to creativity the only person we really need to please is ourselves.

When I think of my favourite images, either my own or ones made by other photographers, the common thread that makes them outstanding is their authenticity, their originality.

As the American realist painter Chuck Close noted, “The fact that you can have something that's recognisable from fifty feet across the gallery as a Diane Arbus or Irving Penn, the fact that you can have recognisable authorship means that they really have done something because it's a damn hard thing to do.”

Photography is perhaps the hardest medium in which to signify authorship because a photograph is in a sense just a facsimile, devoid of maker’s marks. Yet some photographers do manage to produce images that are recognisably theirs. How do we put our stamp on an image, how do we signify that it is the genuine article?

A photographer can make their image transcend its literalness and become theirs by recognising something that no one else has seen or photographed in that way. This is the alchemy at the heart of any great photograph.

Workshop participants sometimes ask me how they might develop a unique style, as if it were a fashion statement. True style in the visual arts is the product of our life experiences, our artistic insights, our emotional responses, and our intellect. In order to develop a unique style we must make images that more fully reflect who we are. All the factors I have mentioned should play a part in how we choose our subjects, how our images are composed and how they are rendered. Style isn’t bolted on, it’s inbuilt. I would argue that even if we don’t recognise the provenance of an authentic image, we still intuitively recognise its originality.

Authentic images are communions between the author and the world. The subject will be one that speaks directly to the photographer and the image is one that they will make in response. That might sound grand but think of it as a private conversation, a cosy chat between the photographer and subject. As the author of the image, the feeling that one gets when viewing these images, no matter how wide the angle of view, will always be intimate.

Simply making a literal image – one that refers strongly to the origin – does not make it original. As Guy Tal has pointed out, a photograph can be an authentic response but not be realistic. What makes an image authentic is the photographer alone has seen it in that way. Someone standing next to you would not have seen the scene in the same way. The particular representation is unique.

Authentic images obviously cannot be pastiches of other photographers’ images. We should not start with a crib sheet printed from a Google image search. Original images are outstanding because they are meaningful to the photographer (and hopefully a wider audience) in a way that yet another image of Maroon Bells, or The Watchman at sunset or the natural firefall in Yosemite can never be. This time it’s personal.

Their authenticity enables these images to rise above the oceans of instants captured by other photographers. But don’t think of a tsunami, think instead of a gentle swell. Outstanding here is about personal fulfilment, but it’s not about being “the greatest”. Being creative isn’t a competitive sport, there are no leader boards and no records to beat. Creativity is a lifelong trek rather than a sprint.

That’s more than enough metaphors for a single paragraph…

The Source

I believe that creativity starts with being inquisitive, with eagerly asking questions, oft times without the hope of an answer.

When I am working, I try to be open to the possibilities for image-making rather than having a fixed outcome in mind. The great American photographer, Minor White, wrote eloquently about this openness:

We should note that the lack of a pre-formed pattern or preconceived idea of how anything ought to look is essential to this blank condition. Such a state of mind is not unlike a sheet of film itself - seemingly inert, yet so sensitive that a fraction of a second's exposure conceives a life in it. (Not just life, but a life).

A decade or more ago, I had a fascinating conversation with a charming man named Ian Biggar. Of the many things we discussed, one anecdote stuck in my mind. He described a conversation he'd overheard on a photographic workshop. The leader had asked a participant ‘What are you trying to say in your image?’ The participant replied, “I’m not sure I am trying to say anything yet. I guess I’m still listening.” This struck me as a very sound basis for photography.

It's important to me that I am making an enquiry about my surroundings in my images, rather than imposing a conclusion. I am not seeking to make definitive statements because I don't know the answers. The questions vary enormously from image to image; I might be asking about the colour of light or what is it that is beautiful about moving water or why I find that arrangement of elements interesting or musing on the ecology of a particular place.

On the rare occasions when I grant an interview (Who am I kidding? I’m happy to blather on about photography to anybody with a pulse and a pen!), I am occasionally asked about my methodology for finding images. Interviewers usually seem nonplussed when I tell them that I basically bimble about until I find something that interests me. The commonest approach to making landscape photographs starts with a location, often a specific view of that place. A goal is set before the photographer even leaves home.

But as J.R.R. Tolkien pointed out, not all who wander are lost. I traverse the landscape like a gold prospector who is searching for a possible strike, turning every rock as I go (not literally, of course!), watching for clues as to where I might find a single, small nugget. My wandering is open-ended but guided by experience. I am acutely aware that on any given day I am unlikely to unearth even a small nugget, let alone the mother lode. My ambition is to make a satisfying/intriguing/enquiring image some time. A few times a year will do. I’m fine with that.

The quest is almost as much fun as the discoveries. Minor White, again, “…a lot of times I photograph with nothing specific in mind. I just play it as it comes. If it's good, fine. I find 'letting it happen' relaxing, a playful vacation. Stimulating pictures almost always result.”

When I’m searching, I enter a hyper-receptive visual state. I often stare at something until it seems to come apart, like a word that you’ve looked at for too long. Ideally, I enter an almost meditative state. But I don’t need to fast or mumble incantations to enter this condition. There’s nothing mystical about it. Psychologists know this as flow state. This is the condition arising from concentrating your whole being on the task at hand. It is a state that we are all capable of through application and concentration.

When making an original image we need to shut out the everyday babble of thoughts unrelated to the task at hand. The preferable state of mind is akin to that of an unexposed piece of film; static and seemingly inert yet pregnant with almost endless possibilities. Whenever we make a photograph, there are a host of alternative ways of photographing the same subject. I try to mentally explore as many of them as I can, searching for the one that best fits my outlook that speaks to me directly.

The image above was made in El Capitan Meadow, Yosemite, yet there’s no sign of that iconic peak; am I perversely ignoring it?

I would counter that by saying that I am always searching for a subject most appropriate to me, one that addresses my interests and concerns directly. I want to ask my own questions of the landscape and to find my own answers.

For me this photo encapsulates time. There are clues to interlocking rhythms of life in this environment, each beating with a different frequency. The fallen log shows evidence of a wildfire, a common feature of this environment. The charring is partially obscured by a fallen oak leaf and pine needles. Leaves fall every year, wild grass fires sweep through every few years, the tall trees here live for a century or more. All this is lit by the blue sky and white light reflected onto the log and leaves by El Capitan’s 900mtr sheer face of pale granite. It took an ice age or two to sculpt this reflector.

It is critical that I remain open to the possibility that anything I see may become an image. A key aspect of this is my striving to avoid any prior expectations of what I may shoot.

Expectation is a serious inhibitor for creativity because, as American photographer Berenice Abbot noted, “If we travel with expectation, we make expected photographs”.

Long before the internet was peppered with cat videos, in his 1976 bestseller “The Selfish Gene”, Richard Dawkins proposed the notion of the meme. This is an infectious, self-replicating idea that mutates according to creative rather than environmental pressure. Photographs can behave like this. Whenever we set out with an expectation to shoot at a well-known spot we have already been infected by a meme. A single image of Kirkjufell wreathed in aurora can thus spawn a million inferior copies.

Expectation is a double-edged sword; it leads us to crave the expected subject and simultaneously makes us less able to see the unexpected. With vast numbers of images of practically anywhere on the planet available on the internet, it has become very hard to travel without expectations.

I am old enough that no internet existed when I first started making landscape images. Back in the dark ages, when working to commission on books and for magazines I was given a typed (!) list and told to go out and see what I could find. At the time I often felt like I had been given too little information. With hindsight, it feels like a wonderful gift to have had very little notion of what to expect. This experience continues to shape the way I make images today.

The Inquisition

For me, every photographic foray is an inquisition, a prospecting expedition. I find the best way to make original images is to simply put down the camera and look, sometimes for an hour or more. I look behind me, above me, at my feet and usually away from the iconic view before eventually raising the camera to my eye.

There are many possible inquisitions but I tend to concentrate on three lines of enquiry.

The Reality Gap

Photography is not about the thing photographed. It is about how that thing looks photographed. Gary Winogrand

One of my overarching motivations for photographing is to explore the gap between how the combination of my mind and eye apprehend reality and how a camera and lens render that. Incidentally, too many landscape photographers think that a photo of a rock is just about how that rock looks. It’s important to remember that subject and object are rarely congruent.

Except when viewing optical illusions, the visual realm seems straightforward. Most of the time we take it completely for granted. We are unaware of the process of seeing: it just happens. Vision is as clear as mountain air.

But anybody who has spent more than a few minutes using a camera knows that transcribing reality into a pleasing photograph can be fraught with difficulties and frustrations. Some of that is technical, and relatively simple to resolve. However, this still leaves questions about the influence of our physiology on human perception (and also about how cultural differences change the interpretation of the light gathered by our eyes). I find these questions fascinating and a very fruitful line of enquiry.

Looking for Answers

I hunger to solve the puzzle of composition. One of the principle driving forces of humanity’s rapid spread across the globe has been a desire to solve puzzles, be they practical, theological, philosophical, or merely whimsical. We appear to be hard wired with this trait. Recent studies using functional MRI scanning have shown that areas of the brain associated with pleasure become very active during puzzle solving. Scientific enquiry, or any other field of intellectual endeavour, is essentially a long-term form of the same itch that drives our desire to solve a crossword puzzle.

For a very long time it was almost impossible to acquire a David Ward photographic print. There were a number of reasons for this but one of the most important was that I saw prints as superfluous. The creative process was what I craved. I wasn’t interested in producing a product, per se. My fascination and satisfaction came from the act of making the photograph, writing the score in Ansel Adams’ terms, rather than the performance. (I did eventually realise this wasn’t the smartest move as a professional photographer!)

In the days when I shot 4x5, the exposed sheet of film represented a solution to the compositional puzzle that I had faced.

Often a week or two would pass between shooting and receiving the processed sheets. I was invariably nervous as I opened the packet. How good was the solution I had found? Would memory and outcome coincide? Had my technique been equal to my ambition? Would the film be capable of rendering my vision? Had I remembered to shut the lens?!

On a few exceptional occasions, laying the film on the lightbox revealed an object as near to perfection as I could imagine. I felt rapturous. This was the climax. Slowly fading bliss would follow, a pale echo of that moment.

In my mind, the goal was achieved. No need for a print that would, in my opinion, not only be redundant but also inferior.

Whenever we make a photograph we are solving a multi-faceted, multi-dimensional problem. We have to balance exposure, colour, tonality, line/form, movement and a dozen other factors. The first of these is the simplest, the rest require a way of thinking that is far from linear. Except in controlled situations, the process of making a photo is akin to extemporary jazz. We have an instrument (the camera) but we’re never really sure how the performance will evolve. This is the opposite of having an expected outcome and, especially for the novice, it is often a scary prospect.

For this reason, photographers do a lot of things to make this process slightly less intimidating:

- Going to locations where they feel sure there is at least one image to be had (e.g. researching honeypots on the internet)

- Visiting places at particular times of day or certain seasons (e.g. the golden hour and autumn)

- Using software tools to find out the timing of events (e.g. tides, sunrise/sunset, weather forecast etc.)

As we grow in abilities and confidence the balance tips away from fear towards inspiration.

Once we’re proficient enough (always practice your scales!) we can be reasonably sure there won’t be any bum notes, but we can never be absolutely certain that the piece will become a memorable classic.

Note: I wrote “a solution”. There can never be “the solution”. There is no single correct answer to these puzzles. If that were the case then two photographers in the same place would always make near identical images. If this does occur (e.g. sunrise at Mesa Arch) it is indicative of how simple that particular compositional problem is. I don’t believe that most of the people gathered in such a situation are trying to solve anything. It’s a bit like filling in a crossword when someone has already given you all the answers. I do believe, however, that whilst not everyone is interested in doing the cryptic crossword, most aspire to more than solving the five minute one.

Searching for Mysteries

I want to explore the mystery of the world by really looking at things, as if for the first time.

The British photographer, Bill Brandt, wrote, “The photographer must have, and keep in him, some of the receptiveness of the child who looks at the world for the first time, or of the traveller who enters a strange country.”

To constantly see the world anew and with a sense of wonder; what a gift to grant ourselves!

He went on to write, “Most of us look at a thing and believe that we have seen it, yet what we see is often only what our prejudices tell us to expect us to see, or what our past experience tells us should be seen, or what our desire wants to see...”

Evolution has inclined us to notice the tiger in the long grass but not the way the grass waves in the wind or the beetle that cling to its stalks. To notice these things we need to do more than open our eyes, we need to open our minds too. Our habit is to only pay attention to those portions of the visual field that help us navigate, avoid threats, to find food or mates. We are constantly bombarded with far more visual information than we are consciously aware of. We discard the ‘excess’ because processing it all requires a lot of effort and is, in evolutionary terms, of little benefit. Except when you are an artist or a scientist making an enquiry of the world.

Surface appearances are often little more than window dressing, hiding deeper truths. The answers to questions about these truths are likely beyond the reach of the photographer and their photographs but I still feel it’s worthwhile making the enquiry. As the American photographer Wynn Bullock wrote, “Mysteries lie all around us, even in the most familiar things, waiting only to be perceived.” For me there is no greater thrill than those rare occasions when I lift the curtain, just for a passing moment, and catch a glimpse of what lies beyond.

The enquiries you make should be driven by your interests, be they political, philosophical, theological or even scatological.

A Bigger Question

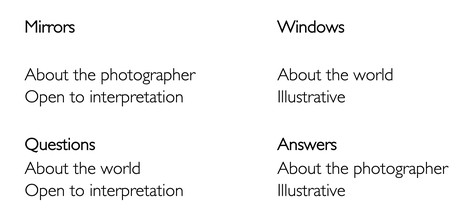

Beyond the personal act of inquiry, I proposed in Landscape Beyond that we might usefully think of all photographs as always being either questions or answers. My suggestion was that trying to make images that were “questions” rather than “answers” would give our photographs more depth and meaning. The first step is to define the terms:

Images that are questions…

…invite us to explore what we feel about the image’s subject. They evoke questions without necessarily providing answers and they tend to be open to interpretation, to be ambiguous. Questions can be both aesthetically pleasing and revelatory. Questioning images don’t attempt to tell the whole story, they are content to be merely an enquiry.

Any photograph made with serious intent is a form of enquiry: its author is asking a question or questions of the world. This may be as simple as seeking the answer to the problem of composition but it may well be a deeper question. The crucial point is that sometimes these questions are answered within the frame and sometimes the image just leaves them unanswered. It is important to state that I am not talking here about the question of composition being unresolved. An unresolved image is one that lacks compositional balance and is aesthetically unpleasing: it is such an ill-posed question that the viewers are not only unsure what they are being asked but are unsatisfied with the form of the image that they are being presented with.

The denotative power of the photograph – “It’s just a rock!” – can swamp the photographer’s subtle questions. They need to work at distilling and simplifying in order to concentrate the viewers’ attention. As Shakespeare said, ’Truth hath a quiet breast’. Ask questions, make your images simple, make them quiet and you may, at the very least, reveal some further mysteries to explore.

Images that are answers…

A photograph that is an answer is predominantly viewed passively; we absorb what they show without much conscious effort. But, in the same way that junk food is pleasant to eat – because it gives an intense but short-lived high – these passive photographs rarely leave a permanent impression on us. An hour, or at most a day, after we've looked at a passive image it is lost to our memory.

A photograph that is a question is more 'difficult' to view than an answer because viewing it requires the active participation of the viewer. Time must be taken to ask questions like “What am I seeing here?” or “What is the photographer’s intent?”

What we get out of photographs is directly linked to the effort that we put into the viewing and it seems clear to me that the photographer's duty is to try and engage the viewer – not simply by making 'pretty' images but by asking something of them in return for the gift of the image. The viewers should sing for their suppers.

I am by no means the first to propose a duality as a way of classifying images. The most obvious example is the objective/subjective dichotomy, an argument that has been running since the invention of photography.

Photographer and museum curator John Szarkowski proposed another in 1978. He held an exhibition entitled “Mirrors & Windows” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York that has greatly influenced subsequent ideas about the interpretation of photographs. The premise for the show was that all photographs are either mirrors reflecting the photographer who made them or windows presenting the photographer’s view of the outside world. The former tell us more about the photographer than about reality. The intent of the latter is to tell us more about reality than about the photographer.

The difference between Szarkowski’s classification and mine becomes more apparent if we look at a diagram.

You’ll notice that the new categories mix the attributes of the old: a ’question’, for example, has one of the attributes of a ’mirror’ and one of a ’window’. I am not suggesting that Szarkowski’s analysis is incorrect, merely pointing out that we might look at photographs in another way.

What benefits might we get from thinking of images in this way? The first is to show that photographs have another level of complexity beyond Szarkowski’s duality. We should know this. I have already discussed at some length subjects such as semiology that have a bearing on this, in my book Landscape Within.

I think that the duality using questions and answers lets us think in a different way about photographs, one that is much more weighted towards thinking about intent than the approach offered by semiology. If we think about images in this way, we must first ask ourselves what might the photographer’s intent have been and have they succeeded? Semiology concentrates more on outcomes rather than intent; it looks at what arises from the image rather than why something was included. There is a good logical reason for this; we can never truly know the photographer’s intent merely by looking at the image. But asking what it might have been is still a useful exercise. It might help us to think about why certain images intrigue us and others don’t. This approach is not intended as a replacement for other approaches; it certainly offers a shallower analysis than semiology may provide. However, one distinct advantage is that it is relatively easy to employ without having to spend years on studying psychology or linguistics.

The questions never end…

I hope I showed in the first part that it is pointless to rail against the massive increase in worldwide tourism and not being able to have well-known places to yourself. My aim with part two was to show that turning your back on the honeypots will improve your photography. According to my proposed definition, most landscape photos on social media are answers. Acquiring these loud proclamations has become the game for many, in a virtual arms race for the spectacular.

There is another way.

Sure, there’s a cost: You’ll need to put in some more effort, you’ll need to properly connect with your subject, and you’ll need to show more of yourself in the image. That doesn’t mean ego, I’m not advocating images which shout “Look at me! Aren’t I clever?!” On the contrary, they should be subtle, like a whisper, a susurration compared to the howling gale and bombast of “The Big View!”

I started this article with a quote from Nan Shepherd. She was an author and poet who wrote passionately and almost exclusively about the Cairngorms, a small part of Scotland. In her masterpiece, “The Living Mountain”, she describes her walks amidst these ancient hills. Her wanderings were often of the “where the fancy takes me kind”. She normally bypassed the summits in preference for some smaller thing that intrigued her. Her goal was to deepen her understanding. She was constantly asking questions of herself and of the landscape she found herself in. It puts me in mind of that other great wanderer, John Muir. He once wrote

Wander a whole summer if you can... time will not be taken from the sum of your life. Instead of shortening, it will definitely lengthen it and make you truly immortal.

Connection with subject comes from asking questions of yourself and of the world in front of the camera. It springs from uncertainty rather than certainty. Admitting that one doesn’t know the answers can be a frightening thing but, as the ancient Greek philosopher Diogenes Laertius noted, “Confidence, like art, never comes from having all the answers; it comes from being open to all the questions.”

By putting the prescribed views off-limits, the Pandemic has already forced some photographers down the road of discovery rather than rediscovery. This isn’t just about making photos somewhere that you wouldn’t have bothered with before. The novelty of these alternative locations has also forced a degree of introspection. Where do I start? How do I make sense of this place in a photo? Do I need to start by listening?

Authenticity in art arises when we enquire of ourselves what we truly think or feel about something, rather than parroting a received viewpoint.

Creative journeys never start with plagiarism, they start with a question; “What if…?”

My final question to you is what if we make our interior world a more important starting point for our work than the exterior? This might seem counterintuitive for landscape photography, but the landscape of our minds is the well spring of creative genius. This is the origin of all art, no matter how humble.

Let the inquisition begin!