Featured Photographer

David Tatnall

David Tatnall has been making fine art photographs in Australia since the mid 1970s. He has worked professionally as a fine art photographer since the mid 1980s. His passion is photographing the land using a large format film camera.

David Tatnall’s photographs have been collected by The National Gallery of Victoria, The State Library of Victoria, Monash Gallery of Art, Australian Embassy in Washington USA, RMIT University Ho Chi Minh City Vietnam as well as many regional art galleries in Australia.

He has been awarded a lifetime achievement award for ‘an outstanding contribution to nature conservation in Victoria through photography’.

He is the editor of View Camera Australia

a site dedicated to the promotion of large format photography and photographers working in darkrooms in Australia.

Chrysalis Gallery represents him in Australia.

Michéla Griffith

In 2012 I paused by my local river and everything changed. I’ve moved away from what many expect photographs to be: my images deconstruct the literal and reimagine the subjective, reflecting the curiosity that water has inspired in my practice. Water has been my conduit: it has sharpened my vision, given me permission to experiment and continues to introduce me to new ways of seeing.

What we see and experience at an early age inevitably shapes our lives and our passions. For David Tatnall it was green on a map, closely followed by the viewfinder’s perspective and walking. From this has come a lifelong passion, and a life’s work.

Would you like to start by telling readers a little about yourself and where you photography started?

I was born in inner Melbourne, Australia, and have lived most of my life close by. I remember as a child going on family outings in our old car. It rarely made it to the destination without boiling or breaking down and while we waited for the engine to cool I spent time wandering about looking and listening; just ‘in the bush’. I recall being shown a map of where we’d been on one trip - Kinglake National Park - and I noticed it was marked green. Other places we went to were also marked green and I began to wonder why only small areas on the map were so coloured. Those family outings had an impact. I realised the really good places we visited were national parks – protected land. My interest in conservation began at that time. I wanted to see more green on the map.

When did you first become interested in photography and what kind of images did you want to make at the time?

I ‘inherited’ my older sister’s Brownie Flash camera when I was young. Our family did recycling before it was fashionable. I regarded each photograph as incredibly special and precious. I suppose the photographs I made were a record of where I went and what I saw. I do recall how special it was to look into the camera’s viewfinder to see the composition I’d made.

The next camera I ‘inherited’ years later was a 35mm viewfinder camera. I calculated exposure using a cardboard dial. This understanding of how the camera’s aperture and shutter mechanisms control light was very important in my becoming a fine art photographer. Photography is all about light. I used that viewfinder camera until I was able to afford to buy a 35mm SLR camera with a built-in light meter. I set up a darkroom under our house and processed and printed all my films. As I moved into secondary school I became interested in walking trips.

Where did you inspiration come from as a photographer?

As I grew older, walking trips were very important to my development as a photographer because I was changing how I photographed. I no longer made reference photographs but began to make photographs of what I felt about the landscape.

A real turning point for me was the destruction of Lake Pedder in Tasmania; a glacial outwash lake protected in a national park that was destroyed in 1972 for a hydroelectric scheme. Photography played an important role in the campaign trying to save Lake Pedder.

I knew a Melbourne photographer, Ian Lobb. He received a grant from the Australia Council to study photography with Ansel Adams & Paul Caponigro in the US in the early 1970s. I recall standing in his darkroom where he showed me the prints made by them that he had brought back to Australia. It was then I realised what a photograph could be. Ian went on to run The Photographers’ Gallery and Workshop in Melbourne. It was there I saw the work of Paul Caponigro, Brett Weston, Eliot Porter and others first hand. I finally had a solo exhibition there in 2003.

As my photography evolved, I saved enough to buy a medium format camera. I used that particular camera for 35 years until it wore out. I bought my first large format camera, a folding 4 x 5, in 1979. I’ve used both medium and large format cameras ever since.

Olegas Truchanas played an important role in the campaign trying to save Lake Pedder. I met him at one of his audio-visual presentations. He spoke quietly and passionately about the need to preserve nature but let his images take the centre stage.

In the 1970s I began to show my medium format colour transparencies to friends at first, then to groups, and finally at public meetings. When the medium format transparency is projected it is a powerful and wonderful thing. At one presentation I meet a sound recordist, Duncan King-Smith. We decided to team up and make audio-visual presentations with my medium format colour transparencies projected via two projectors and a dissolve unit while Duncan’s stereo sound recordings were played.

Our most significant presentation was of a threatened forest in East Gippsland, Victoria. The Rodger River forest piece was 20 minutes long. It was shown in venues as diverse as the Melbourne Town Hall, small country halls, and in an exhibition ‘The Thousand Mile Stare’ at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art in 1988.

We made a number of other presentations over a seven year period. These took a long time to make and involved long periods of time camping in remote locations. We were fortunate to get a number of arts grants to fund the work.

It was a period of significant conservation battles and it showed me how photography could be a powerful force for change.

Where do you now look for inspiration, or draw motivation from?

I still look at the photographs of Paul Caponigro in books and galleries whenever I can. His view of the landscape is something I understand and relate to. His ability to make powerful yet simple silver gelatin prints is an inspiration to me.

As for motivation, being able to say something about our fragile environment by making a photograph and it having an impact and meaning is it.

Bushwalking, hiking, backpacking, trekking, and rambling are all terms for the same activity: walking in nature. It can be on trails and paths, or through the bush without tracks. It can be tough or it can be a simple day trip. The impulse is the same, getting out of the built environment and being in nature.

I have skied cross-country with a heavy pack, through the Alpine National Park in Victoria, camping alone in the snow to make a series of photos that have been collected by the State Library of Victoria. I walk & camp regularly in the national parks that are nearest my home. I try to respect the environment as much as possible. I don’t make campfires I use a fuel stove; I make sure I take home everything that I bring with me.

I am drawn to the landscape that is not ‘heroic’ or ‘iconic’ rather the ‘commonplace’ natural landscape that is the heart and soul of this country.

Victoria is the southernmost state of mainland Australia. The topography is hugely varied and ranges from a high point of 1,986 meters in the alpine region, through warm & cool temperate rainforests on the coastal fringes, to semi-arid ‘deserts’ in the northwest. One of my most challenging walking trips was to a region in northwest Victoria called the Big Desert. The Big Desert Wilderness Park covers an area of 1,417 square kilometres. It is trackless. A multiple day walking trip involves carrying everything including water – there is no groundwater – navigation is by compass. Often people think of it as a featureless landscape but once you have immersed yourself in it the variety of colours, shapes, and vegetation is astonishing. It is a subtle but beautiful place.

Peter Dombrovskis’ photo ‘Morning Mist, Rock Island Bend’ was an iconic call to arms for the environmental movement. What role has your own work played, and what issues are you currently most concerned about?

Actually, it was a call to the heart and soul of the Australian public and its politicians. The environmental movement needed no call to arms.

I have worked closely with the Victorian National Parks Association – Victoria’s oldest conservation organisation - since 1970 over many campaigns to protect the Australian environment, the creation of the Alpine, Errinundra, Snowy River and Murray-Sunset National Parks being the most significant achievements.

I have been given a lifetime achievement award by Parks Victoria (the state authority that manages National Parks in Victoria) and an honorary life membership to the Victorian National Parks Association for ‘an outstanding contribution to nature conservation in Victoria through photography.

Recently I received a grant to make photographs of Melbourne’s largest park – Royal Park – in a campaign to stop a tollway from being bulldozed through it.

Just before COVID lockdowns became normal I was commissioned to make a series of photographs of two significant forest areas: Mount Cole and the Pyrenees Ranges in Victoria. Those areas are now to be included in new national parks.

The protection of Australia’s unique landscape is very important to me but I make photographs in nature for more than political reasons. Here’s an introduction to the catalogue of one of my exhibitions that says it better than I can:

‘Ansel Adams once said that he never made a single environmental photograph. Though David Tatnall’s pictures have often featured in conservation campaigns, it is similarly true of his work that its main purpose is not to make a political point, but to invite the viewer to explore the spirit of the place presented: the context in which the picture is taken may generate a political meaning, but Tatnall’s vision is wider than that of the narrowly political purpose. It celebrates the detail of places long protected, places in contest and places that are still overlooked as worthy of aesthetic consideration. The photographs live on as reflections on landscapes whose land use status has changed but whose spirit still challenges response and interpretation.’

From ‘Seeing the Forest & the Trees’ exhibition catalogue 2003.

How important is it that landscape photography retains this tradition? While social media can be used to raise awareness, do you think there is today confusion between the self and the role that the work can and perhaps should play?

Tradition and nostalgia aren’t big in my life. Although it’s important to know the history of photography, it’s important to look forwards not backwards. The landscape is always changing, in Australia bushfires are a major landscape-changing event.

I make photographs to honour the land. I do that with the photographic equipment I think does that best: a large format camera. My photographs have been used to draw attention to environmental issues, but I also hope that they stand alone as works of art.

Social media is a weird thing. It can be useful to raise awareness, promote an exhibition, and promote a talk or event. It can also be a showcase for work produced; it all depends on how social media is used as to how it’s seen.

Often, the success of a trip is judged (by others) on the images made, but you’ve said (Time and Tide) that you’ll often return with no images. Do you think that people need to focus more on the experience than the result?

Although coming back from a trip with some good photographs is very satisfying, for me it’s not the motivating factor in going on a trip. Being in the environment spending time in nature is why I go. I’ll only make photographs when the light is good. If necessary I’ll wait, put up my tent nearby, or I’ll just not make a photograph.

When everything falls into place, the light is good, the composition works, I’ll first get my tripod out – all of my landscape photographs are made using a tripod. Then the 4x5 camera is attached and opened. I only have three lenses, a standard, modest wide angle and modest long lens and on a long walking trip, I’ll rarely carry more than two. I’ll attach the lens to the camera, but before I’ve got the camera out of the bag, I will have decided on the composition and the lens to use. Then I’ll focus the camera and make any camera adjustments needed. With a one degree spot meter, I’ll calculate the exposure – I use a version of the Zone System to determine exposure. I then make the exposure, pack everything back up in my pack, and move on.

When I go into nature it’s to be in nature, if I make a photograph, it’s a bonus, being in nature is the experience, the photograph is not.

I wrote a while back about time not getting equal billing with light and what happens while the shutter remains open is still a source of much inspiration for me. Part of the popularity of large format is said to be that it forces people to slow down, but it also perhaps shifts the balance back a little. Getting there, pre-visualising, setting up and exposure all take longer and can’t be rushed. Do you think that adds a greater depth to both our experience and understanding of a place and the images we make?

Using a large format camera is a slow experience, but so is landscape photography. I’ll wait for the light, sometimes minutes, sometimes days. On walking trips I don’t carry many film holders, I try to make each one count, so waiting and taking time is part of the process.

Understanding of place does come from spending time in that place. Watching the light move and change is all part of the experience. Hopefully, it does add depth to the images made.

Would you like to choose 2-3 favourite photographs from your own portfolio and tell us a little about why they are special to you, or the experience of making them?

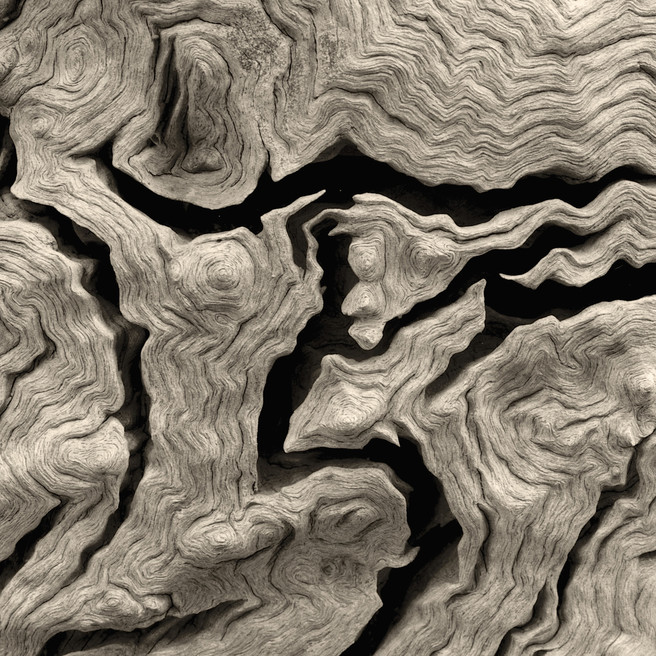

These two photographs are linked. The first is ‘Snow Gums, Bogong High Plains 2001’. The second is ‘Burnt Snow Gum, JB Plain 2003’. Both are from parts of the magnificent Alpine National Park. In 2003 a massive wildfire burnt for over 59 days burning the majority of the 660,000 hectare national park.

I made the 2001 photograph on a walking trip across the Bogong High Plains about 1,800 meters above sea level. I camped near these stands of ancient Snow Gums and made this photograph as they vanished in the mist.

I made the 2003 photograph on my first trip back to the Alpine National Park after the fires. It was devastating. Those magnificent trees were reduced to burnt black trunks. I only managed to make two photographs on that trip, this one is the strongest. Both were made on my 4x5 camera using the standard lens.

You mentioned earlier that some areas recover, others are never the same. Have you had a chance to go back and see how the park has fared?

The ferocity and intensity of recent wildfires have made going back to places very difficult for me. Although some plants and trees can survive and regrow after fires this may take decades. Some trees such as Alpine Ash, Mountain Ash (the tallest flowering plant in the world) and Snow Gums don’t survive fires.

The entry road into the Alpine National Park was like driving into a cathedral of massive Alpine Ash trees. These trees if burnt regrow from seed in the ash bed, to reach the height they were would take over 100 years.

The frequency of fires has increased due to climate change and the regrowing trees have been burnt again before they could produce seed. Now the drive into the park is like driving into a cemetery of huge dead trees with no young trees to take their place.

The same goes for forests of Mountain Ash, now massive dead trunks. Snow Gums if burnt can reshoot from a lignotuber at the base. It can take many decades for these trees to reach several meters tall. Once again the increased frequency of fires in the alpine region that would only have a fire once a century means they now have had too many fires in succession for many of the trees to survive.

Digital printing has made outputting our images simpler (though this is not entirely true if it is to be done well). What do we miss as a result? What can the darkroom still offer today, and how much of your print process is analogue/digital?

For me, photography is about the physical print, seen on a gallery wall. My benchmark in excellence in photographic printing are the silver gelatin photographs of Paul Caponigro and the dye transfer prints by Eliot Porter.

I process and print all my black and white photographs in my darkroom. My colour work was all made on transparency film until recently. It was processed at a professional laboratory. I now use colour negative film.

All my vintage colour prints are chromogenic prints. I’m still able to make them at the moment but in Australia, that process is becoming increasingly expensive and less available.

Although inkjet prints have become the norm for colour printing worldwide I still prefer chromogenic prints for their depth of colour and subtle tonality.

Photography has always evolved, otherwise, we would still be making daguerreotypes and suffering brain damage from mercury poisoning! Photography will continue to evolve. I continue to use film as it gives me the tonality and excellence I want in the prints I make. I’m not nostalgic about it. I own a digital camera but I enjoy using the film camera a long way from towns and cities; a camera that doesn’t require a battery to operate doesn’t beep at you or require updating and simplifies the art of making an image.

One of the big issues using film-based photography now is how best to show it in the digital sphere. Digitally captured images look great on a computer screen, but rarely look as good as prints. Film based images have to be scanned to be seen digitally and usually don’t look as good on the screen, but look much better as prints. I have adapted and continue to adapt the techniques I use to accommodate these issues.

How has the pandemic affected your plans? Did you have a chance to try anything new or different, or did you find any unexpected ways to be creative and remain motivated while you’ve been subject to restrictions?

The ongoing restrictions caused by the global pandemic have affected everyone. It’s frustrating not being able to travel particularly as this year is one of the best wildflower seasons Western Australia has had in decades. In Victoria, we’ve had average rainfall over winter so everything is looking good.

However, I have a native garden at home where I make photographs and I live near two urban waterways: Merri Creek and Darebin Creek. Both are short walks away and I take my camera there to make photographs.

I’ve had a close association with the Merri Creek for many years. I’ve walked the whole 72 kilometre length of it and have had three solo exhibitions of the photographs I made there over the past 30 years. It is one of my continuing long-term photographic projects.

Not being able to go further afield to make new photographs has given me more time to spend in my darkroom printing. My printing techniques have improved and changed over the years and I have been revisiting my old negatives finding new insights in them.

Has the nature of the images that you make, the things that call to you, changed in recent years? The ‘intimates’ on Instagram prompted me to ask you this.

Using a large format camera where the image is viewed both upsides down and back to front I look for patterns when composing photographs. If you look at ‘Burnt Snow Gum 2003’, for instance, the image works both upside down and the right way up.

I’ve always made photographs of close ups or intimate subjects as well as the big view. Essentially my impulse to make photographs hasn’t changed but my technical ability has developed over the years. It’s possibly best described in this essay by Philip Ingamells:

"David Tatnall’s photographs record exactly what is there. No drama, no contrived perfection, but a resonant perfection nonetheless.

Frustratingly, he does this through viewfinders that present the image the wrong way around. It is as if he either has an uncanny ability to view the picture upside down and inside out, yet in his mind’s eye see it the right way around or, more intriguingly, he uses this impediment to great advantage, composing a most natural and realistic image as if it is an abstract.

I don’t know if I have ever asked David how he does this, or if I ever want to. I expect and prefer to believe, that he is not sure what he does anyway.

The result is quite fine. Almost alone amongst artists and quite rare amongst modern photographers, he takes us to the natural world without artifice, without emphasis, without decoration, without altering a thing. And he opens our eyes and our hearts to something enduring, something very great."

From the essay ‘Upside down and inside out’, by Philip Ingamells, environmental educator and activist.

Do you have any particular projects or ambitions for the future, or themes that you would like to explore further?

I’m working on an exhibition at the moment that’ll be held in late 2022 or 2023. I’m also engaged in a number of long-term photographic projects. The Merri Creek I already mentioned is one. Another is called ‘Land Bridge’; it’s a series of photographs of the Victoria coast, Bass Strait Islands and Tasmania, which were all joined together before the last ice age in a ‘land bridge’. Another project is called ‘Woodlands’. This is a series of photographs of what might be described as ‘ordinary’ bush.

Can you say a little more about what this is like (ordinary bush)?

The ‘ordinary bush’ is best described as the hard to photograph non-iconic or monotonous landscape.

I’m drawn to this for several reasons; firstly it’s very much under threat. Firewood collection, land clearing for agriculture and many more impacts threaten the ‘ordinary’ bush. Secondly, it’s hard to make compositions, as there aren’t many straight lines. I enjoy the challenge of making sense of this landscape within a photograph.

You’ve taught photography workshops and been an artist in residence - tell us about those. You’ve also travelled a lot overseas making photographs.

I’ve taught workshops in large format and pinhole photography for over twenty years. I’ve also led photographic trips to Nepal and within Australia. I’ve retired from teaching workshops now but I still mentor a number of photographers.

I was Artist-In-Residence at several remote state-run secondary schools in Victoria and over a twenty-year period I taught around 6000 students film photography. We used simple 35mm film cameras and colour negative film. I encouraged the students to see using the camera. I found it extremely rewarding working with them.

I’ve been very fortunate to have travelled a lot in my photographic life. Nepal was and is one of my favourite places; I’ve been there nine times. Antarctica, The Andes in Peru, India, Italy and Bolivia are also stand out places.

The alpine environment in Australia has always been very special to me. I also really like spending time in the arid regions too.

In fact, if the light is good I’m happy where ever I am.

Many British photographers have fallen in love with Dombrovskis' work, in some cases via Joe Cornish and On Landscape's features about him. Could you recommend any less well known books or photographers from the Australian landscape scene?

‘The Mountains of Paradise’ by Les Southwell is the first to come to mind. Les was an engineer by profession, a walker and photographer by passion. This book published in 1983 is a showcase of Les’s photographs of Southwest Tasmania. All made on a 35mm film camera.

This book is regarded as a classic of Australian landscape photography.

Les was still active well into his eighties. His body was found outside his tent on Victoria’s highest peak Mount Bogong in 2017. He was 88.

‘Wild Places’ by Peter Prineas with photographs by Henry Gold documents the wilderness areas of eastern New South Wales; published in 1983.

Henry Gold immigrated to Australia in 1955 and was an active walker and campaigner for the protection of the natural world.

He was awarded the ‘Medal of the Order of Australia’ in 2006 for “service to wilderness preservation through the use of photographic documentation”.

‘Range Upon Range – The Australian Alps’ by Harry Nankin is a series of large format colour photographs documenting the alpine region of mainland Australia; published in 1987.

‘Southern Light – Images from Antarctica’ by David Neilson; published in 2012.

This collection of photographs of Antarctica and the sub-Antarctic made on large format camera is the result of six journeys between 2002 and 2008.

Often people think that they can’t add much to the big environmental issues. Do you think most photographers have the capability to support the environment with their photography, for instance by raising awareness of local issues?

Being aware of environmental issues is foremost. Being aware of the carbon footprint created by making landscape photographs must be considered and offset.

Simple things like including environmental information in the photograph’s caption is one small thing a photographer can do. Finding out as much as you can about the location, the plants, the animals that live there and what threat – all land is under some kind of threat – that land faces is another small thing a photographer can do.

Being politically active by using photographs made about environmental issues may not make you popular. But it will help the environment. We all must do something.

Whether a photographer uses their photographs to raise awareness or just get involved by picking up rubbish, pulling out weeds or donating money, getting involved is the important thing.

Thank you, David.

David has undoubtedly succeeded in his ambition to see more green on the map, but I doubt he will see it as ‘success’, with more always to be done. I think however that David would be disappointed if all you took away from this article is that his photography is about conservation. While his images have undoubtedly been a good and faithful servant to it, they are first and foremost about his relationship with the land, and the spirit of place.

Despite all of this, he sees a photograph as a bonus - being in nature is the primary motivation and satisfaction.

You can see more of David’s photography at http://davidtatnall.com. He’s also on Instagram and Facebook.

If you’re fortunate enough to be in Australia – or able to travel there at some point – you’ll find David’s prints at the Chrysalis Gallery.

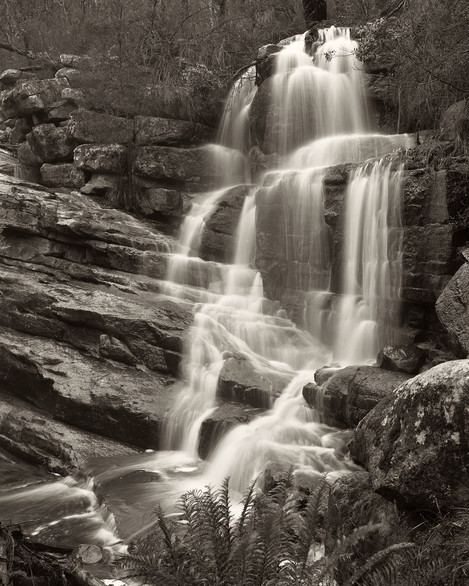

- Splitters Falls. Grampians National Park

- Mount Emu Creek

- Yellow Gums. Little Desert National Park

- Yerrung River Mouth. Cape Conran

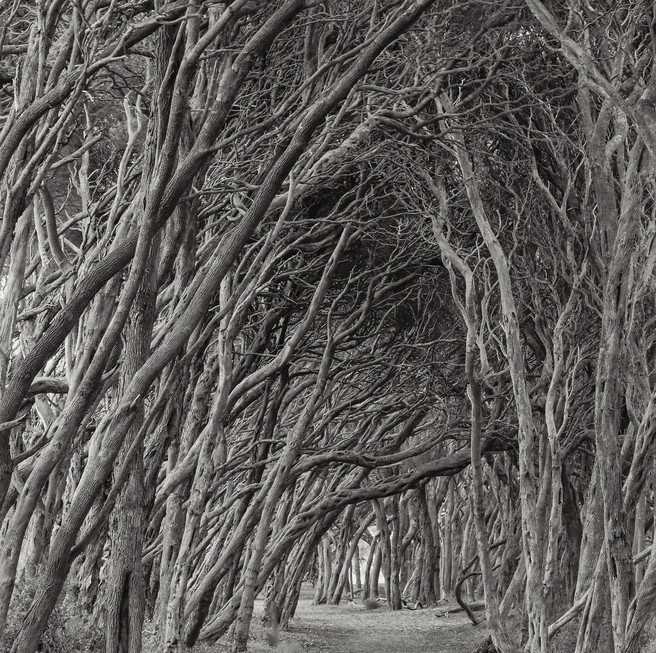

- Tea-tree forest. Bunyip State Park

- . North West Point. Erith Island

- Black Spur. Yarra Ranges National Park

- Shipwreck Creek. Croajingolong National Park

- Snow Gums. Baw Baw National Park

- Merri Creek in Northcote

- Black wattle

- Snow Gum & Crb Hut Dinner Plain

- River Red Gum. Woodlands Historic Park

- . Little River Gorge. Brisbane Ranges National Park

- Cape Liptrap

- Cape Conran

- Ellery Creek. Errinundra National Park

- Mount Buffalo National Park

- South East Point. Wilsons Promontory National Park

- Cape Conran

- West Cove. Erith Island

- Moonahs. Blairgowrie

- Mount Emu Creek

- Splitters Falls. Grampians National Park

- Burnt Snow Gum. Alpine National Park. 2003

- Snow Gums. Bogong High Plains. Alpine National Park. 2001