Kate Maxwell chooses one of her favourite images

Kate Maxwell

I am currently based in the Welsh Marches, surrounded by open hills and farmland. I have always enjoyed photography, but bought my first digital camera as a sketching tool for the paintings I was making at the time, and joined a local camera club to improve my skills. I became a “proper” photographer when asked to supply images for a local estate agent. When The Photo Space gallery opened in Ludlow, I was lucky enough to win its first competition for local photographers, leading to a solo exhibition. I am never happier than when wandering about outdoors with a camera to hand.

I came to photography from an interest in art; indeed I bought my first digital camera as a kind of sketchbook, to record what I saw as references for future paintings. So when I stumbled upon the work of Franco Fontana, I was mesmerised. His vividly colourful abstract images of the Italian countryside reminded me of some great 20th century painters: Mark Rothko, Richard Diebenkorn, Piet Mondrian, Nicolas de Stael.

Here was something completely different from what I was used to seeing in landscape magazines or Instagram. There are no epic vistas, moody mountains, glowing sunsets or Big Stoppered rushing rivers.

Fontana, now 88, is little known in the UK, but his photographs are in major collections all over the world, including the V&A in London and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. He has published over seventy books and been widely exhibited in the world’s classiest galleries. He has also worked commercially with big brands such as Volkswagen, Versace, and Volvo, and his images have been featured on jazz album sleeves.

The Italian landscapes that caught my eye were shot during the 1970s and 1980s on 35mm transparency film, with a telephoto lens, underexposed slightly to saturate the colours. In a 2009 documentary (available on YouTube) he describes how he then photographed the slide with negative film, which had the effect of intensifying the colour and removing the shadows, giving the flat colour blocks that make his work so distinctive.

At the time, serious landscape photography was mostly in black and white, and in Britain usually had a documentary slant - Fay Godwin and James Ravilious are two examples who spring to mind. This lends a fine art feel because it is not how we actually see the world; stripped of familiar colour, it is already an interpretation using tone and graphic shapes. Colour at the time was considered too realistic, too amateur, too commercial. There were colour photographers in America who challenged that belief, such as Joel Meyerowitz and William Eggleston. However, their work was strongly rooted in time and place; with most of their images, you feel you could walk into the scene and become part of it. There is a narrative, storytelling aspect to them. Fontana’s images seem to transcend place and time; they are not of something, they are about creative vision. His landscapes are real places taken in real time, but they are not literal depictions of the scene. They are, like a modern painting, less about the subject than about the photographer’s response to the subject. He is quoted as saying: "Photography should not reproduce the visible; it should make the invisible visible”. Through his eye and mind, the landscape is transformed into something beyond what you or I might have seen had we been standing next to him.

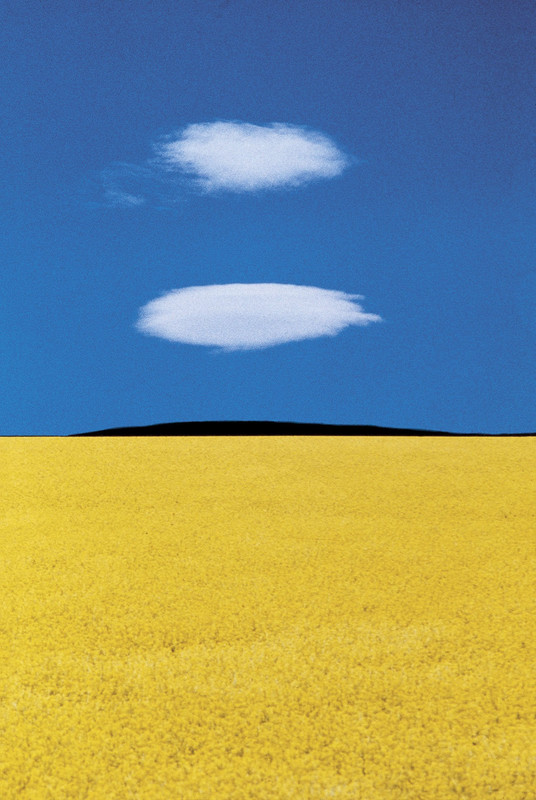

The image here, just titled Puglia, 1978 (as is the whole series), could be said to break most of the composition rules to which landscape photographers today are often slaves to. The horizon line cuts across the centre of the image, breaking it into two halves. The two clouds (even, not odd numbers) and the distant hill are dead centre. There are no leading lines to take us into the picture, and there is no single focal point. The sky is blue, not dark and moody or inflamed with sunrise or sunset. There are no shadows to create form.

The scenes for which he is famous, of Puglia and Basilicata in southern Italy, are probably unremarkable country scenes which most of us would drive through on our way to something more spectacular, only stopping to make an image if the weather conditions or light made them remarkable. The cultivated agricultural landscape is not dramatic, it is just rolling farmland, similar to what we might find in southern England. He was, he says, attracted to this area because of the wide open spaces, with few trees, telegraph wires or roads to break the rhythm. By focusing on the essential shapes and patterns of the fields, Fontana transforms them into something unique with his exceptional eye.

Today he uses a DSLR and Photoshop but, like many masters, he says the camera is just a tool, as the pen is to the writer. It’s what you do with it that counts: “The camera is simply the instrument that allows us to represent our thought.” This, he says, can be achieved with a camera phone, and he welcomes the new technologies which enable more people to express themselves. His other works are also worth looking at; his minimalist seascapes have the same central horizon and flat colour planes. He also has a great collection of geometric American urban landscapes, with shapes and bright colours flattened under a blue sky, and his series Asphalt cleverly observes the graphic lines which you see if you look down towards your feet on roads and pavements.

I think we can learn from him that great photographs don’t have to be of spectacular, iconic places. There are interesting images to be made all around us; we just have to look harder, and pursue what resonates with our own personality, curiosity, and imagination to find our own voice.

It’s the mind, not the camera, that creates a memorable and unique photograph.