Kathleen Pickard chooses one of her favourite images

Kathleen Pickard

One of my greatest pleasures in photography is uncovering the unfamiliar in the familiar. When I hear from a viewer that “I live here but I’ve never noticed that before!”, I smile in satisfaction. Beauty is often hiding in plain sight, but it takes practice to see it.

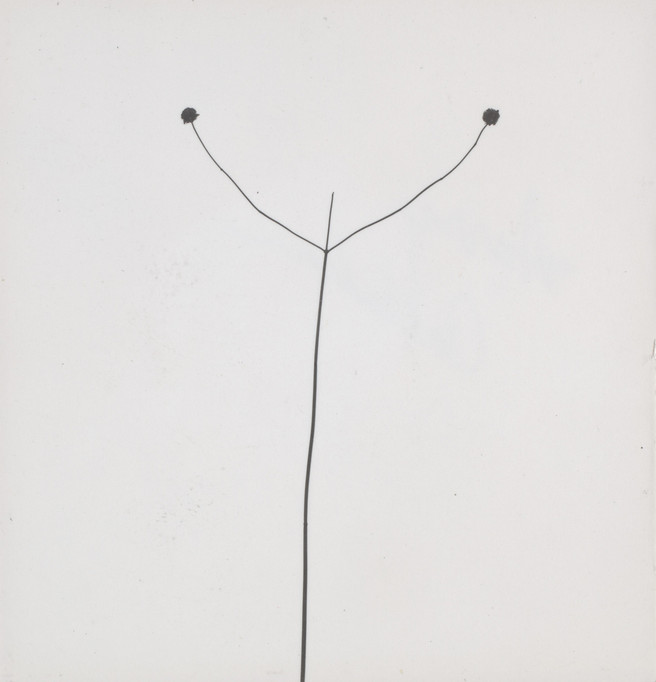

When I was approached to write a piece for Endframe it didn’t take me long to decide upon my image selection, “Weed Against Sky, 1948" by Harry Callahan. The photograph is deceptively simple - an arrangement of black lines sitting comfortably on a white ground. It is not a descriptive image. There is no colour, no scale, no context. It is an image distilled to its minimum; sparse, cool and abstract. It challenges the viewer to engage with it.

In 2010 I attended an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. It had the title of “Abstract Expressionists New York: The Big Picture.” It was a comprehensive display of the art scene of New York in the 40s and 50s. The usual suspects were in attendance: Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko, to name just a few. To my surprise, among the large colourful canvases, I found a group of modestly-sized black and white photographs by a photographer with whom I was totally unfamiliar, Harry Callahan. The images were a shock to me, not just because they were there at all, but because his subject matter was my subject matter: weeds in snow, stones in the sand, reflections on the water. Things that most often go unnoticed in the larger landscape.

I felt an immediate sense of kinship with this unknown (to me) photographer.

I needed to explore and find out more about him.

I discovered that in the art world he is considered one of the most influential American photographers in the 20th century. He is credited with being the first photographer to make abstracts in nature. Between 1946 and 2020 his work was exhibited 51 times in that temple of modern art, MOMA. In 1978 he was the first photographer to represent the USA at the Venice Biennale. He was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 1996. And that is just an abbreviated list of his achievements. Why then is he not a household name?

Callahan was a late starter. He was 26 before he took his first photograph. He had no training in photography and was largely self-taught. He joined the Detroit Photographic Guild but found that their favoured genre, pictorial photography, accompanied by their dogmatic views on how it should be made, was not to his taste. He termed it “murky junk”.

However, it was at the Guild where he experienced his photographic epiphany. He attended a lecture and workshop given by Ansel Adams. Adams’ work exhilarated him; but it wasn’t the famed grand landscapes he found exciting, it was the less-appreciated images of grasses. Seeing those photographs freed Callahan. They gave him permission to photograph anything, anywhere. He decided, right then and there, that his life would be making fine art photography. In reality, as he soon discovered, there was no prospect of earning a living from his photography.

His good friend and colleague, Aaron Siskind, termed Callahan “a restless photographer’’. Fortunately, his income from teaching supported his family while allowing him to follow his own photographic path. He would photograph a subject until he felt he “got it right”, however long that took, be it hours or years. He would then move on to new subject matter, a new camera, or new experimental techniques. He returned to nature repeatedly throughout his career but also shot street, urban, and architectural photographs. His wife, Eleanor, was an unending source of inspiration. He photographed her almost daily for over 15 years.

Callahan was a pioneer in colour photography, shooting transparencies from as early as 1941. Unable to afford dye-transfer prints of his work at a teacher’s salary, the slides went into storage and were shown only after 30 years had passed. He shot in-camera multiple exposures and what would now be called Intentional Camera Movement. He explored ideas to their limit, performing hundreds of variations until he was satisfied. His perseverance resulted in an archive of over 100,000 negatives and 10,000 proof prints that was left in the care of the Centre for Creative

Photography at the University of Arizona when he died in 1999.

So, I had to wonder, given his accomplishments and innovations, why I wasn’t as familiar with his name as I ought to be.

Perhaps there are several reasons.

His portfolio is so diverse that he defies categorization. He actively avoided developing a style saying that when you did you were “sort of dead’ creatively. It’s not easy to recognize “a Callahan” in the wild.

His confidence in his art was rock solid, but as a person, he was shy in the public eye and spectacularly self-effacing. A somewhat dated 1981 interview with him, available on YouTube, provides ample confirmation of that. Self-promotion must have posed a significant challenge for him. He let his photographs speak for him.

Mostly, though, I think it is another factor that contributes to making his profile lower than it deserves to be. At the time he was photographing there was a large market for both social documentary images (think Life Magazine and its ilk) and the Grand Landscape. The work of the photographers in those genres was out there in the public eye, available to be seen and thus more likely to be recognized and talked about.

Callahan was a photographer of the intimate landscape, or as John Szarkowski, Director of Photography at MOMA, put it, his photographs “were the interior shape of his private experience”. At that time there simply wasn’t an appetite for that kind of photograph in the market.

Whatever and however Callahan photographed it was done with great authenticity. To Harry Callahan photography was life and his life was photography. In his own words, “I’m interested in revealing a subject in a new way to intensify it. A photo is able to capture a moment that people can’t always see. Wanting to see more makes you grow as a person and growing makes you want to show more of the life around you. I do believe strongly in photography and hope by following it intuitively, that when photographs are looked at, they will touch the spirit in people.”

You can read more about Harry Callahan in a short article On Landscape wrote in 2011 alongside the books "Elemental Landscape" and "The Photographer at Work" which we can highly recommend.