A new book of images of water

Keith Beven

Keith Beven is Emeritus Professor of Hydrology at Lancaster University where he has worked for over 30 years. He has published many academic papers and books on the study and computer modelling of hydrological processes. Since the 1990s he has used mostly 120 film cameras, from 6x6 to 6x17, and more recently Fuji X cameras when travelling light. He has recently produced a second book of images of water called “Panta Rhei – Everything Flows” in support of the charity WaterAid that can be ordered from his website.

Abstractions of nature have not left the world of appearances; for to do so is to break the camera’s strongest point – it’s authenticity~Minor White

During the 2021 COVID lockdown, I produced a book of photographs of water called The Still Dynamic, in aid of the charity WaterAid, that seemed to be quite well received. At least the limited edition of 100 copies sold out quite quickly. While the PDF of The Still Dynamic is still available for download, I found I had enough images from walking through Mallerstang and Switzerland in the last year to produce another volume, this time called Panta Rhei1. Since it is for a good cause, I hope you will not mind this article to publicise the book.

Panta Rhei, translated as Everything Flows, is an aphorism that is often used as a short summary of the concepts of the Greek philosopher Heraclitus of Ephesus, who lived (approximately) from 535 to 475 BCE2. Little is known about his life and since all of Heraclitus’ writings were lost, apart from a few fragments, it is not clear that Heraclitus actually used the phrase himself (it has been implied from the later interpretations in Plato’s Cratylus and Simplicius of Cicilia)3. One of those fragments, however, expresses the same idea as You cannot step twice into the same stream. As a hydrologist, I am very aware of this aspect of my subject. Rivers persist, but their characteristics change over a range of time scales, from the single rainfall event to their geomorphological history, and the water in them is forever being renewed.

From the fragments that do survive, and more so from later writings about Hercalitus, it seems that he was more concerned with fire as a (perhaps metaphorical) driving agent for change than water. He was, however, one of the first philosophers to address the issue of process dynamics and to give process the role of an explanatory feature of nature rather than as something to be explained4.

As a hydrologist, Panta Rhei is also a homage to the International Association of Hydrological Sciences (IAHS), which celebrates its centenary this year. IAHS has used Panta Rhei as the motto for a decade long initiative with the aim of encouraging research on the interaction between water and society5. There is no doubt that anthropogenic effects on the hydrological cycle in many parts of the world are having an increasing impact, both directly through the exploitation of water resources for industry, agriculture and hydropower and indirectly through climate change. It is not that change has not been long recognised in hydrology, but that the societal impacts are still not sufficiently understood. This includes the impacts on the hydrological extremes of floods and droughts and the feedback of those extremes on vulnerable societies. The pollution of waters and its impact on biodiversity is also an important issue in many places. Water security, in terms of both quantity and quality, is becoming a critical issue in many parts of the world, including the potential for cross-frontier disputes between nations.

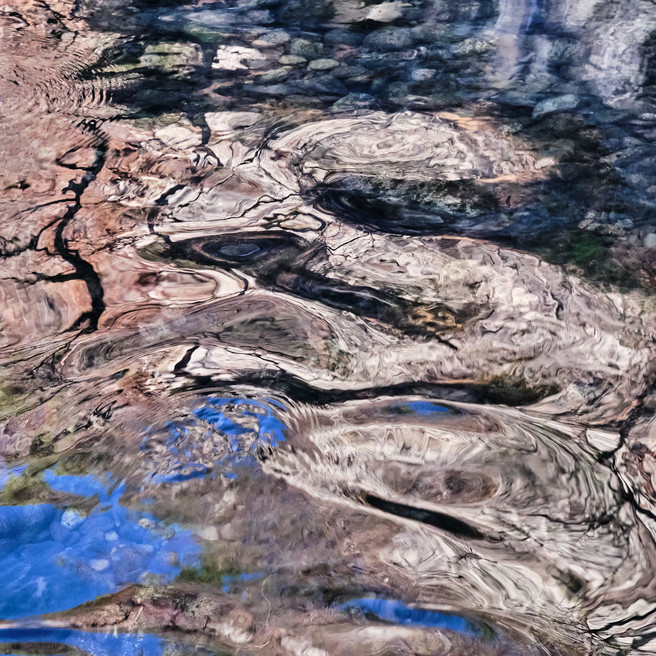

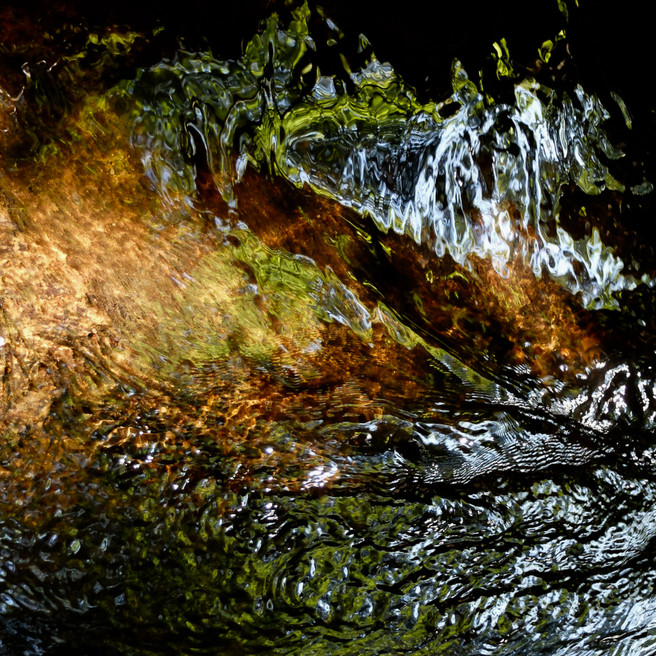

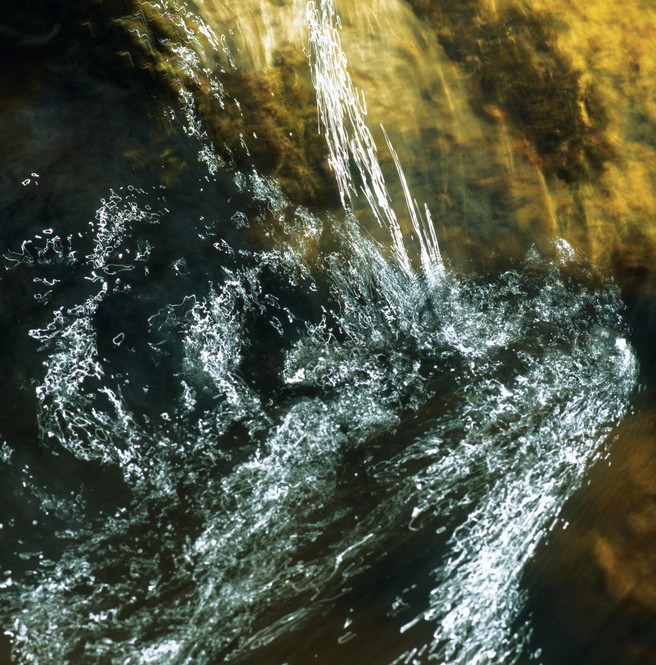

The collection of images of water in Panta Rhei does not deal directly with these larger aspects of change. It rather tries to address the challenge posed by water to the photographer. Everything Flows but to the photographer, that also creates a fundamental difficulty in representing such change in a still image. I discussed this in a couple of previous articles for On Landscape6. It is a challenge to capture the fleeting changes of light and flow in a way that still implies the nature of a flow in a way that is indeed still dynamic. As a hydrologist, of course, I should have some understanding of the way in which water flows through the landscape, but such knowledge is necessarily approximate and uncertain since many of those pathways are hidden beneath the surface, and where the water is visible in streams and rivers, the patterns of flow are often highly complex in response to the detail of the boundary conditions of the flow. This is something that has proven attractive to film makers for a long time. The Dutch film maker Bert Haanstra (1916-1997) directed a monochrome film called Panta Rhei in 1952 (that can be found on YouTube7) that used a variety of techniques, including time lapse photography, to illustrate the change of water in the forms of clouds, drops, streams, and waves, and the light reflecting from water surfaces.

Still photography has to stop the motion (or integrate that motion over the time scale of a longer exposure). This would appear to be a disadvantage but also provides some useful possibilities. The first is that the stilled motion can be explored in all its complexity and detail, at the viewer’s leisure, in a way that the eye cannot either in nature or in video – the movements are just too fast to follow. The second is that creative techniques, smoothing the flow lines or recording the light trails of reflected light on the surface, can be used to represent the nature of the motion in ways that are lost to the eye in real time. These can be seen in the images below.

Another aspect of the Heraclitus fragment, and its later use by Plato and others implies more than the nature of change in nature. It implies that we are always changing as well. A second fragment states: "We get into the same river and yet not into the same river, we are and we are not [the same]." In terms of my photographic practice, it has certainly changed over time: as a result of gaining experience; of spending time with different streams with different characteristics; of changing light when returning to the same stream; of changing from film to ever better digital cameras, though some of the images in Panta Rhei were still taken on film.

In fact, I have now taken many thousands of images of water in its different forms but capturing images I am really satisfied with remains a challenge. It perhaps helps in using digital cameras to be able to see what has been captured on the spot, but I still find that many do not turn out as pre-visualised while other images are unexpectedly magical when viewed on screen or as prints. I would at least like to think that I have got better at choosing when to press the shutter over the years but, even then, the rapidly changing nature of the flow also means that multiple images taken in succession can be more or less successful in terms of the patterns of light traces or the splash and bubble tracks that are produced on the film or sensor. In general, the images are underexposed with minimal post-processing (usually only raising the shadows and increasing the contrast.

Taking a photograph involves making a selection from nature. Most of the images I have included in the book are selections of only a small part of nature, creating found abstractions8. I generally choose to take photographs of small selections because it is easier to find a satisfying balance of elements. Interestingly, with the cameras I have, I mostly cannot get too close, so the images are mostly no smaller than a bit less than 1m square……but perhaps this is the smallest scale that can be considered as landscape, in that it must include a number of interacting elements of form in a semi-abstract way.

Even at that scale, it is difficult to find perfection in all the elements because of the random nature of things not being in quite the right place or not being able to view from the right direction. But, of course, those imperfections are also part of the nature of a place; anything that appears perfect is also unrepresentative. This is what gives rise to the tension of the choice - what the Japanese call Wabi Sabi, seeking the perfection of transience and imperfections. To frame an image, I am seeking something that is well balanced in form and colour, even if complex in structure and textures. Making semi-abstract and minimalist images is perhaps a way of finding satisfaction more easily, avoiding things for the eye to seize on and critique. In that way we can just enjoy an abstract image as a selection from the wonder of nature. I hope you might enjoy the images in Panta Rhei. Others may be seen at www.mallerstangmagic.co.uk where the book may be ordered in hard copy or pdf.

References

- A few of the images have already appeared in earlier articles in On Landscape including https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2021/12/interpreting-the-found-abstract/ and https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2022/05/parallelism-of-ferdinand-hodler/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heraclitus

- See https://www.thecollector.com/panta-rhei-heraclitus/

- https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/process-philosophy/

- https://iahs.info/Commissions--W-Groups/Working-Groups/Panta-Rhei.do

- https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2017/04/the-science-and-art-of-hydrology and https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2019/01/physics-of-caustic-light-in-water

- See https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2021/12/interpreting-the-found-abstract/