Documenting a trip of a life time

Claude Fiddler

I started making pictures in 1979 on a winter ski of the John Muir Trail. The trail traverses a 211-mile-long route along California’s Sierra Nevada. The trip set my life course. I had been skiing and rock climbing on high school and university semester breaks but after the Muir Trial trip I made my way into a life in the mountains.

In 1983 I started using a large format camera, and for 30 years I only used the 4x5 with one lens. The one exception was in 1983 on a trip to climb the West Ridge of Mount Everest. In 2008 I bought into a digital camera and lens. I currently use a medium format digital camera.

I am most interested in the mountain environment. Living in the High Sierra Nevada I’ve been able to have a long-standing and deep relationship with the Range of Light. I’ve also been travelling to the Arctic Brooks Range of Alaska since 2004. A truly remarkable landscape. For me, to make my best photographs, I need to be intensely involved with a place. Multiple long trips over multiple years are what works for me.

Stacking the Deck

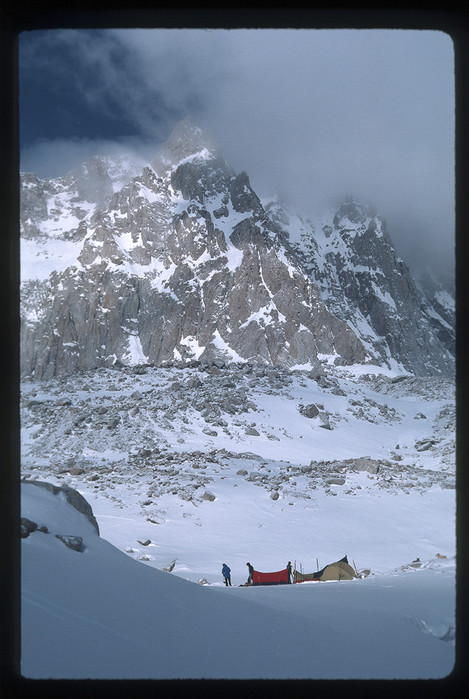

During the winter of 1979, my friend Jim Keating and I skied the John Muir Trail from Mount Whitney to Yosemite Valley. The 211-mile-long trip took us 33 days. 11 days of storms kept us in the tent napping, reading, and catching glimpses of the falling snow out the tent door. Friends joined us for the start of the trip from Whitney Portal to a camp just below the steep climb to Trail Crest. Trail Crest at 13,777 feet is the high point of the Muir Trail. A foot and a half of snow fell when we got to camp, and we were forced to sit out the storm and eat part way through our 10-day food supply.

I snapped photos of the trip, starting with our departure from my Bay Area home. The camera was Dad’s Kodak Contina with a Zeiss lens. I was using Kodak Kodachrome 25 film. I used the distance scale on the camera to focus. My goal was to take photos as a way to journal the trip. I’d been influenced by a slide show Galen Rowell did at a nearby high school. Six to 10 of us watched Galen’s presentation. I had grandiose plans to make my living as a photographer which I was sure would happen after this momentous trip. I had admired Ansel Adams photography. The perimeter walls at the Yosemite Lodge Dining Room restaurant had probably sixty Adams photos. Back in my high school days, I could admire these while waiting for an ice-cream sundae. As a teenager, I spent most of my waking consciousness thinking about rock climbing. But Adams’ photos affected me in a different way than climbing. Climbing was all about feeling personal accomplishment. The photos made me aware of the representation of the scene and the object, the photo itself.

The storm ended, and Jim and I were forced to confront post holing knee-deep steps to the crest of the Sierra, which we did. At the top of the crest, the wind had scoured a spot where we could put on our skis and head down and into the winter landscape of the Sierra. At Crabtree creek, we stopped to make camp. We had our camp set up routine memorized from shake down trips we had taken that winter to get ready for the Muir Trail. This was our first day deeper into the Sierra, and our day-to-day routine became our day-to-day life. The next day we turned north, paralleling the headwaters of the Kern River.

After a cold morning start of coffee, warm granola, and cold boots, we skied along a gentle upward grade over the Bighorn Plateau. The crest of the Sierra sat on our right shoulder. Off to our left, the peaks of the Great Western Divide, Milestone, Midway, Table, and Thunder etched themselves into the western horizon. An endless series of ridges dropped from the crest and divide into the trench of the Kern River. This was the first time I felt that I was inside the High Sierra. Inside a place where lake basins and peaks and streams were there to discover and explore. Not as someone who wanted to conquer a climb or capture with a photo. But as someone who wanted to know what a place was about.

We were in a steady low angled climb headed north toward Foresters Pass on the Kings-Kern Divide. My breathing and the black TRUCKER ski graphic on the front of my skis were my meditation as I was pulled toward the rhombus shape of Diamond Mesa.

I snapped photos of the view, of Jim skiing, giving no thought to lighting or composition. My only thought was to document our progress. We stopped for lunch in the rolling terrain below Foresters Pass. A wind was picking up from the west signalling an approaching storm. As we looked up the south side of the pass, we could see that we would be able to keep our skis on for a while, but the point would come when we would have to boot-kick steps toward the top of the pass. The top of the pass did not look good; the final section had a cornice overhanging the only route to the top. The snow slope below the cornice steepened into a vertical wall. We tightened the rope climbers on our skis and did kick turns until it was too steep to keep skis on. We took our skis off and strapped them to our packs. We didn’t have a rope or crampons or ice axes. We stopped under a rock overhang about one hundred feet below the top of the pass. We thought it better to go one at a time up the headwall in case someone fell. I tried to erase the thought of Jim somersaulting down the rock-hard snow.

Jim went first, a ski pole in each hand turned upside down so he could stab the handles of the poles into the snow. This didn’t work, and at times, all Jim could manage were thin slices into the snow. I watched Jim move steadily and with deliberation. He eventually made the last moves up and out of sight over the top. As Jim disappeared, I forced myself into a tunnel vision of what I needed to do next. I was very afraid of the prospect of a serious fall. The only thing I could do was to move and not hesitate or waver once I started climbing. I had to trust, not accept, the holds as they were. There was no looking to Jim for help or encouragement. There was no edging out over the cornice to watch my progress or demise. I cinched down my pack and headed up. The wall threatened to pitch me backwards. It was imperative to stay balanced over my feet. Trying to stab in my ski poles was a dangerous move that could easily throw me off balance. I had to look and precisely place my feet where Jim had left impressions in the snow. The start and end of my world were a six-foot circle in front of my face. I didn’t let the thought of the wall getting steeper at the top divert my attention. At the final pitch to the top, my mind swirled, knowing I was close to safety, pitching backwards could kill me. I concentrated on the next moves I needed to make. Then I was looking over the top. There were no good holds, only smooth, wind hardened snow at the summit tabletop. Jim was there but needed to stay just out of reach. In a move, I heaved the top half of my body onto the deck of the summit, knowing my feet would lose purchase. I squirmed for inches until I was safe off the north side of the pass. I didn’t turn back to look at the view. Getting down to additional relief was not a given.

A grey bank of clouds and a strong western wind stung us with snow pellets. We put on storm gear and found a spot just down from the pass to clip into our Troll three-pin ski bindings. We pushed off into the Bubbs creek drainage. At the tree line, we stopped at a spot far from any avalanche path and stomped in a tent platform, and burrowed into our sleeping bags as the snow started to fall at a steady rate. Soon enough, snow was hissing off the rain fly and building up the sides of the tent.

The trip up and over Foresters and the relief of making camp before the storm exhausted me. The storm pinned us down, but I welcomed not having to think about getting up in the morning, packing gear, and pushing off. But we were going through the food. We calculated that we had two days of food left. Our cache at Bullfrog Lake was a long day away. The storm lasted three days. On the third morning, the air was cold, and there wasn’t a cloud in the sky. Three feet of snow had fallen so we would be breaking trail down Bubbs creek and then twenty five hundred feet up to the food cache. My only hope for mental survival was to embrace the monotony of trail breaking for hours on end.

We marched through the day anticipating the goodies in the food cache. We’d stashed the food under a prominent and easily identifiable boulder near Bullfrog Lake. When we pulled up onto the lake, we could see the boulder and hurried over to our treasure. We easily dug down to the boulders covering our plastic encased food. Shreds of plastic started to appear as we dug our way to the mangled remains of what was supposed to be a food orgy. We were stunned at our stupidity. We sorted through what was left of the food. At this point in the trip, we were 10 miles from the Kearsarge pass trailhead and another day into the Owens Valley. A moment of reckoning was upon us: stay and make camp or bail out just as the trip was getting real. At this moment, Jim and I figured out that we had ten days worth of food. We’d have to cook pancakes for lunch at some point, but at least the robber rodents didn’t drink our stove fuel. So that was it. On we would go. We didn’t think about how to give up. We thought about how to keep going. This same type of situation arrives many times in the course of an adventurer’s life. At times the hardest thing to do is stop and turn around and call it a day. There are times when the signals all point to a disaster in the making. There are the times when the decision to stay or go isn’t clear but what’s the worst that could happen is a prudent thought. These considerations were not something that I had a lot of experience with at the time of the Muir Trail. In a very direct way the decision to continue was my presentation of the dragon to be slain. The thought of the ease of bailing out was replaced with knowing that skiing out would have been quitting on myself. I would not find out what it was like to ski the Muir Trail. It would be easy to find a way to distraction or move on to a mental comfort zone after ending the trip. The decision to continue the Muir Trail gave me a campaign medal and an experience that set my life course.

A wedge of Parmesan cheese and a couple of M and Ms provided additional but limited encouragement.

On we went toward Glen Pass. The sun angle was high enough that the snow on the south side of the pass had consolidated. At the top of the pass, a long north side descent across a bowl of snow led into Rae Lakes. We tied on avalanche cords. 75 feet of nylon cord with small metal arrows that were meant to lead to an avalanche buried a skier. The cord, according to the how-to pamphlet, would float on top of a running avalanche. A long traversing ski brought us onto the flats of the chain of lakes. The snow was deep, and we needed to link two ski poles, attach a water bottle and lower this down to open and running water. A technique we figured out on our pre-course skis. Long mellow touring led us through open stands of pine. The peaks had changed from craggy granite to colourful metamorphic formations. Side creeks of the Kings River crashed through stream boulders. At times the slope we traversed was a continuous flow to the river. The thought of sliding into the turbulence got me to concentrate on the grip of my ski edges. The days were long enough that I could soak in some warmth.

At Marjorie Lake, we made a planned early stop. We’d brought along psychedelic mushrooms to see if getting further into the Sierra was possible. We brewed tea and took the recommended dose, and stood on our ensolite pads. Soon enough, we were able to yell and get wind swirls to drop down the peaks across the lake. We amazed ourselves for hours.

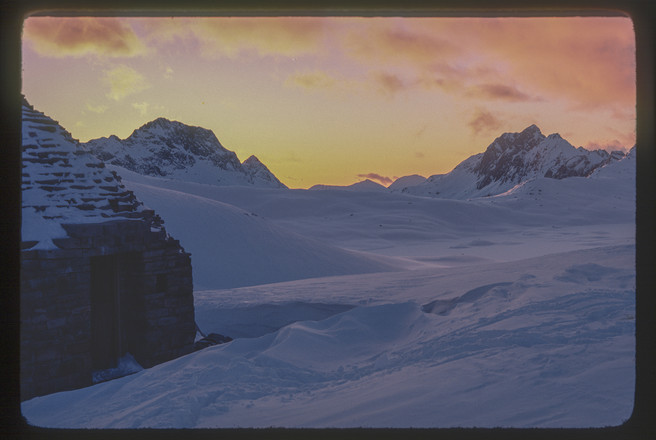

The sun arced to the west, and the cold evening breeze pushed us into the tent.

Parts of the following days were warm to the point where a jacket wasn’t needed at a rest stop. Crossing Pinchot Pass into Upper Basin and the headwaters of the south fork of the Kings River, I got more of a sense of the geography of the High Sierra. Over that pass, there was Lakes Basin, and just over that ridge was Window Peak, and that big flat spot is Arrow Lake. To our right, Split mountain marked the south end of the Palisades. Reading the map, my mind extended beyond the Muir Trail into the complex of the mountains.

For some unknown reason, we decided to put klister kick wax on our skis in Upper Basin. It wasn’t like our rope climbers weren’t working. These were lengths of knotted nylon rope that we threaded or skis through, with the knots ending up on the bottom side of the ski. The knots gripped like tank treads. The rope cost a dollar and fifty cents at Sonora Hardware. Maybe the decision to put wax on was that we’d brought along a pot full of hard wax and klister. We broke out the stove and heated the toothpaste like tube until we could squirt blobs onto the bottoms of our skis. The wax was supposed to be smoothed out, but we achieved a bumpy, inconsistent mess. The wax did grip well, however. We marched toward the V shaped Mather Pass. We were constantly hungry at this point, and the thought of getting to our food cache at Blaney Meadows was haunting our thoughts. Switch backing up Mather Pass proved to be a straightforward series of kick turns. At the top a slight north breeze was blowing. From the top of the pass, mountains swept out like arms from the body of the north facing snow bowl below us. The right arm bent at the elbow and stretched to form the fingers of the Palisades. The left arm bent around the Palisade Lakes. Snow plastered the wall of Middle Palisade. A sheet of cold powder snow blanketed the northern bowl below us. The klister sticking to the bottoms of our skis was going to glue cold snow to the bottoms of our skis. We sacrificed a shred of clothing and stove fuel to clean the klister off the skis. The cleaning was worth it. A run through silky smooth powder-snow took us to camp on Palisades lakes.

I took a picture, a vertical, of Jim making elegant turns down Mather. This photo, along with a few others, distilled my experience of the Muir trail. After the trip it was fun to do slide shows for friends. Our photos telling the tale. But it was only a handful of photos, mostly the grand landscape, that were important to me and set the course of my photography. Early on in my photography, I would only use a large-format-camera.

The next day we traversed down Palisade creek toward Le Conte Canyon. The snow on the south facing side hill was hard, steep and a fall would have serious consequences. At one point, as I was edging hard, my sunglasses fell off and started to skitter away. This was a disaster in the making. Lucky for me, they stopped on a button of snow. I carefully side slipped to the retrieve. At the bottom of the creek at the confluence with the Middle Fork of the Kings River the trail turned right and north into the 5,000-foot vertical relief of the canyon granite walls. We made pancakes at the turn. Gray clouds were moving in fast from the west, signalling another storm. After pancakes, we hastened to make as much distance up the canyon as we could. The thought of breaking trail for 4,000-vertical-feet kept us moving until evening. By this time, snow was coming down hard and the threat of avalanches was on our mind. The thought became reality as we heard the roar of an avalanche echoing in the canyon. We stomped down a tent spot and surmised that being uphill and across the river from the granite slopes of Langille Peak were enough to keep us safe. There wasn’t much of a choice of where to find a safe camp. The canyon walls formed a perfect funnel for avalanches. We were at the bottom of the funnel.

During the night, we would wake up and hold our breath as avalanches roared down the canyon walls.

In the morning, just as it was getting light, I asked Jim for a weather check. He unzipped the tent door a bit and said it was still snowing. As I was slipping back to sleep, a huge roar came barreling toward us. We could hear tree limbs snapping off as an avalanche thundered uphill toward our tent. Snow hit the tent and encased us in a white and yellow tomb. We carefully unzipped the tent and brushed the snow away from the entrance. We made our way out into the still snowing daylight. We pulled the crushed tent out of the debris. We are at the very end of the avalanche. One hundred feet toward the river, and we may not have emerged. As the snow was sure to keep piling up, we skied back down to the ranger cabin we had passed and broke into comfort and safety. A day later, the snow ended, and we broke trail to Muir pass and the stone hut at the top of the pass. It was cold inside, but we were out of the wind, and we could sleep on the frigid benches inside. The massive Wanda Lake and the curving Evolution Valley swept down the San Joaquin River headwaters. We had a day and a half of food left. The high peaks of the crest didn’t crowd in on the valley, and I no longer felt hemmed in or that I was skiing in what could be a dangerous place. We were descending to the south fork of the San Joaquin and making another turn north to reach Blaney Meadows and our food cache. At the low elevations along the river, we found exposed sun-warmed granite boulders. It felt luxurious to take our boots off and warm our feet on the granite. The warmth made me realise that I’d been cold for two weeks.

We eventually skied into a grove of aspens. Many of the tree trunks were carved with old sheepherder porn from the turn of the century and more modern petroglyphs. I would have thought more about the human need to imprint the earth with our passing, but we had a bouillon cube and a tea bag left for food. At the Diamond D dude ranch, our food was intact in the 55-gallon drum where it was stored. We ate until it hurt. There is a hot springs at the ranch, and we luxuriated in the hot water, washed our clothes, and waterproofed our boots.

We continued onto Reds Meadow, where our food was in an upside down trash dumpster. We dug down to our food, and set up the tent next to the nearby hot springs. No one was there. No ski tracks. No snowmobile tracks. Just over the hill was the town of Mammoth Lakes. Still in the stages of being a funky unplanned resort where someone could live in a Teepee, do summer of construction work, scarf food from dumpsters, ski all winter, and be homeless when that was something cool.

In this familiar territory, we skied along San Joaquin Ridge with the Minarets and Lyell Range to gauge our progress. The snow on the dark rock of the peaks etched every detail in this scene. We camped at Thousand Island Lake and had a gentle ski to Donahue Pass. Standing on top of Donahue, the long, gently curving Lyell Canyon flowed west to Tuolumne Meadows. The Meadows, as they were known, had become my physical and spiritual home. I’d spent the past three summers rock climbing there with Tom, Alan, Vern, Nick, and Bruce. For me, every part of being in Tuolumne was perfect. There was the carefree life of rock-climbing on the most beautiful granite. Walls of golden glacial polish, and streaks of dark feldspar crystals made the climbing varied and intricate. Climbing puzzles to solve. The parking lot at the Grill served as a natural gathering post for the climbing denizens. Early morning sun and the last rays of the setting sun blessed climber’s battered vehicles. I drank endless cups of coffee in the Tuolumne Grill and rewarded myself with a cheeseburger after a day on the crags.

This was a life I would enjoy until the mid-1980s.

We made it to the park service Visitor Center turned winter shelter as the sun was setting. There was no one there. The next day Jim and I ate the remainder of the psychedelic mushrooms and did pack-free runs down Lembert dome. The skiing felt fast and free. The snow was staying on top of spring melt-freeze corn-snow. Back at the Visitor Center, a group had joined us. When they asked where we had come from, we laughed when we said, Mount Whitney. It felt weird to hear our voices conversing with other people. Talking about the trip made me feel the Muir Trail was the world for me and that the other stuff, day-to-day life, the oil embargo, and the coming of Ronald Reagan were a separate reality.

We skied through the Cathedral Range the next day. Traversing past Cathedral Peak, the peak where John Muir felt he was attending church, and I had climbed at least once a year since I was sixteen, the feeling that this adventure was about to end and what I was going to do in the short term crowded into my thoughts.

We camped one last night and the next day hiked down the Mist Trail to Happy Isles in Yosemite Valley.

The trip was over, but my range of life had just begun.