exploring UK & Scottish forestry policy

Ted Leeming

From traditional landscape and the impressionist, to more recent explorations of land use, climate and biodiversity, my work centres around an evolving consideration of place that forms the ‘Zero Footprint’, low carbon concept I share with my wife and fellow photographer, Morag Paterson. More recent works include the collaborative Energise, Fantastic Forest Festival and Artful Migration residencies, Where the Wild Things Are, and an immersive ‘Commute’ - by ebike - from Scotland to Italy. Find out more about our work please visit our blog, “Wanderings of a Photographic Duo”

Since its invention, the photograph has been a powerful medium for telling stories, raising awareness, propaganda and even changing behaviours. An obvious example is the use of the image in advertising and the impact this has had on consumerism. Ted Leeming has been considering the power of the image as both a positive and negative force and exploring different ways we present information to illicit a desired response.

In a recent project, he adopted a picture essay approach for a piece exploring current forestry policy, practices and management in the UK & Scotland today, adding a commentary to a series of images to tell the story. “There are a couple of ongoing forestry consultations taking place at present, and the essay seeks to inform a range of interest groups about the current status of the industry,” explains Ted. “I was struggling to say all I wished through the images alone, so decided to add a commentary based around data gathered from third parties to emphasise the points I was seeking to make.

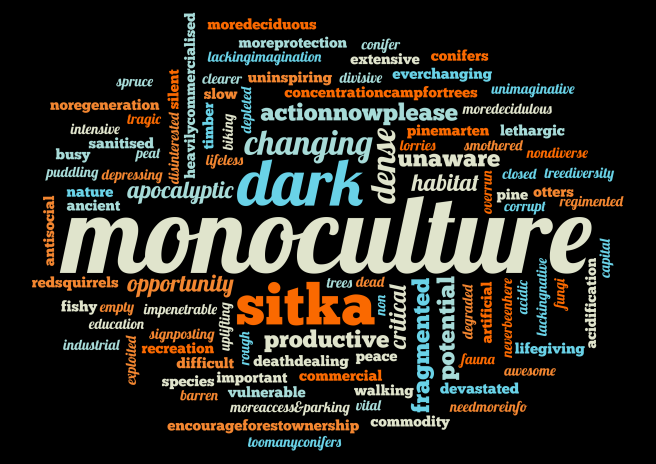

“The essay forms my response to a community consultation & artist residency Morag [Ted’s wife] and I undertook as part of the Fantastic Forest Festival held in Galloway, Scotland, in February 2023. At various events throughout the residency (and via postcards left in local shops and community centres), we asked people, ‘What 3 words describe forestry in Galloway today?’ We created a word cloud based around the responses we received, from which the essay emerged.

“It was an experimental approach, with story, subject and engagement at its heart whilst seeking to listen to the quiet voices in the community that often go unheard. We’ve been incorporating a range of ideas in recent projects, which have also allowed me to draw on my wider passions for the environment, geography and anthropology. Engaging with communities, interest groups, and experts is fascinating and requires us to consider a range of perspectives as we develop our own thinking and outcomes.

“We are always learning, and I think one of the most useful things I have done recently is take time to more clearly define my purpose as a photographer. In doing so I increasingly find myself working more locally and forensically, using a greater range of both attributes and senses and applying them to current issues that resonate with personal values. I think the great Nan Shepherd, in her book The Living Mountain, puts it perfectly when she says, “I knew when I looked for a long time that I had hardly begun to see.” This greater level of reflection is helping me set boundaries and define the types of projects I want to work on, freeing me to more clearly express my thoughts and ideas, which is very rewarding.”

If you are interested in any of the issues raised in the essay or know of anyone who might be, please feel free to contact me at tedleeming@me.com

At 13% of land cover, the UK has one of the lowest levels of tree cover in Europe. According to the Woodland Trust, just 7% of our woodlands are in a good ecological condition. Industry, environmental organisations and the Government all agree that we need more tree cover throughout the UK.

Ancient temperate rainforests are of the most rare and valuable habitats in the UK, comprising of less than 1% of woodland cover, and yet few of these incredible ecosystems are designated. A YouGov poll found that 93% of the British public supported their increased protection.

Many of our existing woodlands are under threat from multiple sources. These vary from site to site but include overgrazing, invasive species, development, storms, drought, pollution, pests and diseases. As a result, many of our woodlands are slowly dying or disappearing.

Current policies are focused towards new planting schemes. 75% of these are being delivered in Scotland, with CONFOR, the industry body, saying that the UK Government is well behind on delivering its stated annual objective of 30,000 hectares of new planting by 2025.

Half of all new schemes in Scotland are for single species conifer plantations, of which 50% are concentrated in southern Scotland. Argyll and Perth & Kinross in Scotland and Wales are also witnessing large numbers of proposals.

729 commercial conifer applications have been approved across Scotland since 2015. None have been refused consent in that period, and only 4 have required an Environmental Impact Assessment [source: Scottish Forestry]. The sheer number of commercial conifer applications in some areas is increasingly controversial.

Commercial forestry proposals have focussed largely on upland pastures and hillsides, displacing traditional farming activities and open moorland species. The result is increasing conflict between different interest groups.

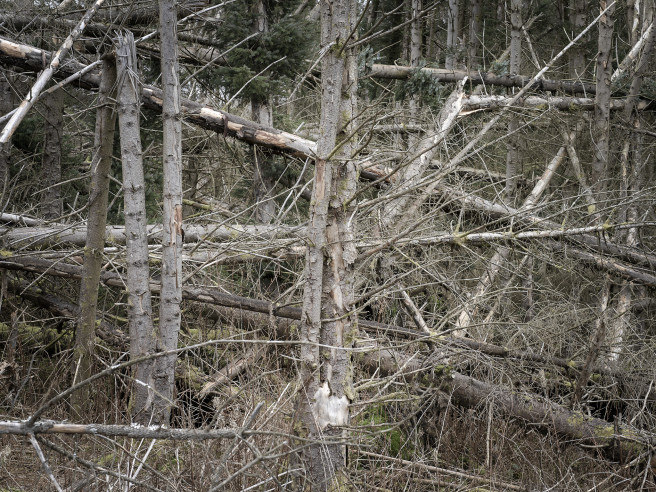

The cumulative impact of multiple forestry applications is becoming a significant issue in some areas as adjacent schemes merge and fragment landscapes and habitats. There are few checks and balances to curtail over-development.

The extent of biodiversity within conifer plantations is contentious. The industry argues that biodiversity within a plantation is increased over existing land uses. The Woodland Trust, however, states that ‘non-native plantations in particular require management to improve their ecological condition’.

Woodlands are important for local economies and jobs. However, many, like the independent forum, The Forest Policy Group, argue that the industry should and could contribute much more to local economies, supporting and promoting small to medium enterprises and local long-term jobs.

Forests store carbon, both in the tree itself and in the soil. Forest Research, the Government’s own advisers, conclude that clear fell plantations are unlikely to absorb the amount of carbon released from the soil over a 30 year rotation period if planted on peaty soils 30cm deep. Despite this, Government policy continues to allow planting on peaty soils up to 50cm.

At the end of the first rotation, it is standard practice to clearfell sites and replant with more conifers. This can be undertaken with minimal assessment, even on peat soils of 50cm or more where new planting is banned.

Most forestry products (including paper, cardboard, wood products, biomass fuels and wood based panels) sequester carbon. But the industry's own figures state that over 40% of clear fell forestry products sequester carbon for 5 years or less, and just 27.3% sequester for longer than a single plantation rotation [source:

CONFOR]

15% of forest products go to supplying the increasingly questioned commercial biomass industry [source: CONFOR]. The UK’s largest commercial biomass plant, DRAX, has recently been dropped from an index of green energy companies following concerns with respect to its environmental credentials.

Drainage is used to reduce the amount of water within plantations. Such drains dry out the soil, releasing carbon and increasing the acidification of watercourses. Data shows a river in southwest Scotland to be the most acidic in Europe, with acidity peaks enough to kill juvenile salmon [source: Smyth].

The industry says it is being judged on schemes planted in the 1980’s and things are very different now. Many others say they see only cursory differences (relatively small areas of broadleaf & open spaces), with large scale replanting & new densely planted, single species conifer plantations across many hillsides.

The threat from unprecedented storms can have a catastrophic effect on plantations. In 2021, Storm Arwen flattened some 16 million trees of largely plantation forestry in a single night [source: BBC]. With climate change, such storms are predicted to become increasingly frequent & severe.

Pests & disease are a major threat to sequestration targets, and storm and drought events can trigger outbreaks [source: Økland and Bjørnstad]. A bark beetle that attacks Sitka spruce is currently causing significant damage to forests in Europe and southern England. If it reaches Scotland at any point in the next 30 years, it could wipe out up to 1 million hectares of conifers. Diverse planting reduces such risks.

Prices for low grade agricultural land have increased at least 5 fold since 1993

[source: Savills]. Many attribute this at least in part to attractive investment forestry policies, subsidies and tax breaks, resulting in what some are describing as ‘the second clearances’.

Forests can be valuable resources for recreation, wellbeing and wider community benefit. But conflicts are being exacerbated by an ongoing reluctance of some developers to allow access over previously accessible land or to meaningfully consult with local communities.

Tree planting is subsidised by the taxpayer, whilst commercial forestry incurs no income tax, capital gain or corporation tax. Annualised investment returns over the last 15 years have averaged 18.9% at one investment house [source: Gresham House].

Some are now saying that with the current speed of change, it may already be too late for southern Scotland and that lessons urgently need to be learned to prevent a replication across other areas of Scotland and the UK. Locals disagree and continue to campaign for more diversity & sensitivity in planting, together with community involvement, in order to deliver a better balance between biodiversity, climate, community, societal and commercial needs.

Communities for Diverse Forestry say that to deliver solutions, all parties urgently need to work together with a mindset of compromise and partnership. At present, however, there is a polarisation of views as interest groups defend existing positions with respect to competing land uses and environmental demands.

There are many exemplary projects across the UK, both large and small, that showcase innovative and more traditional approaches to the delivery of Government targets. All include some form of compromise, but many offer a greater balance for biodiversity, climate and society than the current approach.