Relationship with landscape, narratives and play

Simon Dent

Simon Dent is a British artist. He studied BA Fine Art at Newcastle Polytechnic from 1984 to 1987 and MA Fine Art from 1989 to 1991 after which he moved to Valencia, Spain, returning to England in 2013. His work has been exhibited at The Photographers’ Gallery, London, Impressions Gallery, York, and in many group shows including Towards a Bigger Picture at the Victoria & Albert Museum and Tate Liverpool.

Dent’s work has been published in several contemporary photography magazines including Creative Camera (1988), Aperture (1988), Camera Austria (1991), Uncertain States (2019) Landscape Stories (2020) Artdoc Magazine (2023).

The accident of the random place where childhood takes place has an indelible imprint on one’s relationship with one’s surroundings. In my case, building microcosms in the humid grass, playing hide-and-seek by the crags, climbing trees in the woods and jumping into the cold beck are the childhood experiences that helped to build a playful relationship with the natural environment. Student and then adult life led to cities and to decades of living abroad in a dry Mediterranean climate where land had no mystery and seemed to be nothing but property. Memories of the lost childhood experiences crept into dreams, and a growing melancholic nostalgia demanded attention.

Decades ago, while showing my young son a Japanese children’s picture book of a man’s journey through landscapes of Europe1,

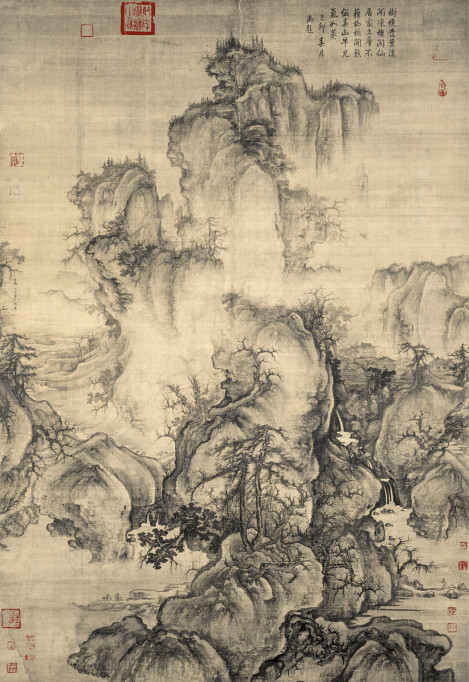

Shanshui Hua (山水画) is an ancient (11th Century) style of traditional Chinese landscape painting that depicts natural scenes, including mountains, water and waterfalls. Reading these and similar Japanese and Korean landscapes, the eye is taken out of Western perspective and into a two-dimensional space that moves through time as the journey unravels vertically and horizontally along symbolic and suggestive paths, bridges, rocks and trees in the visually poetic journey through the landscape. The ancient Shanshui artists explored the relationship between urban life and people’s yearning for nature3.

They developed a code of representation that included winding Paths that lead to a Threshold and then a Heart or focal point that defines the meaning of the painting. The rhythmic movement of lines used in calligraphy and ink painting developed into innovative techniques for producing multiple perspectives, which the most renowned Shanshui artist, Guo Xi, called ‘the angle of totality’. This allegorical style of painting allowed the artists to relate mood to the natural scenes: light and dark, mist and vapours, and so create feelings of lightness, sadness or tranquillity4.

I recently returned back to live in the north of England. The hills and valleys have a rich history covered by woodland moss. In the 8th Century, the English monk and historian, The Venerable Bede, called this last British Celtic kingdom to fall to the Angles Silva Elmete: The Forest of Elmet. In his collaboration with the photographer Fay Godwin, the poet Ted Hughes described this area of the Calder Valley, west of Halifax, as ‘an uninhabitable wilderness’ before it became the ‘hardest worked river in England’ in the introduction to Remains of Elmet5. The combination of poetry and photography tells stories that take the reader to wormholes through the history and geography of the area.,

310 million years ago, the water from the tops of the soggy Pennine hills cut deep, ebbing and flowing valleys through the grit and sandstone and down to the valley of the River Calder. Before the railways and canals were built, these streams powered the early industrial age, and the paths beside them connected communities. Now, the moss-covered ruins of derelict mills and overgrown pack horse trails along the valleys tell what ‘remains’ of this history. These photographs were taken in this wild woodland area along the flowing water through the seasons with Shanshui paintings in mind.

Cameras are Time Machines that can transport one back to the emotions of when the frame was taken. However, the intentional use of visual references, composition and allegory takes one on quite another journey that connects past and present cultures through shared visual language. Ink on silk calligraphy gave no room for error, but photography allows control of intention through a process of reduction. Some of the process is about what is intended, but much more is about what is not. The photographic process involves a conceptual but intuitive framing, distancing and focusing that reduces the real field of perception to a very different composed rectangle. The reduction eliminates unwanted figures and highlights those desired.

The rangefinder facilitates peripheral vision and multiple, slightly different, frames of the same scene, and the depth of field control allows for evocative suggestion of elements similar to ‘the angle of totality’ – then the editing identifies the overly composed and formal; the picturesque or bucolic; the romantic and the plain boring - or the interestingly banal that fits the intention. A sense of timelessness is one of the intentions that determines this reduction. Completely natural scenes are of interest, where only trees, trails, thresholds, rivers and stones appear - Signs of modern life are not.

Cultivating paradox through the gentle juxtaposition of elements generates the same childhood pleasure as described above: The flow of water over the stillness of stone the movement of leaves in the wind. The Daoist juxtaposition of the enduring and the ephemeral6 is mirrored by the photographic instant - and a lifetime.

Why? Who is this for? The idea that an artistic expression of harmony was an allegory for reinforcing the dominant social foundations is still a compelling argument. Landscape art has long been associated with power and order, especially in 11th Century dynastic China. My early artwork from the mid-1980’s, created during my ecological awakening, addressed a feeling of helpless alienation. However, at this moment of environmental crisis, creating lyrically evocative narratives that connect us to our landscape is an act of resistance. This way of perceiving the natural world has also become a personal way of building a playful relationship with the landscape that addresses memory, nostalgia, history, landscape, place, storytelling and the passing of time.

References

- Anno, M. (1997) ‘Anno’s journey’ Penguin Publishing Group

- Quote taken from Ward, P. (2021) ‘The archive of Bernard Taylor’ Understory Books

- Whittaker, A. ‘On Immateriality in Guo Xi's Early Spring’ Pavillion Gallery https://paviliongallery.com/issue-one-immaterial/guo-xi-alexander-whittaker

- See Guo Xi’s “Treatise on Mountains and Waters (山水訓)” quoted in China Online Museum https://www.comuseum.com/painting/masters/guo-xi/

- Hughes, T. and Godwin, F. (1979) ‘Remains of Elmet’. Faber and Faber Ltd.

- Phrase taken from Spirn, A.W. ‘The Language of Landscape’ (1998) Thomson Sore, p.156