Oceano: An Elegy for the Earth

David Ulrich

DAVID ULRICH is a professor and co-director of Pacific New Media Foundation in Honolulu, Hawai‘i and a faculty member at UC Berkeley. He is an active photographer and writer whose whose photographs have been exhibited in more than 75 one-person and group exhibitions. He is the author of several books including The Mindful Photographer: Awake in the World with a Camera (Rocky Nook, 2023) and his first monograph, Oceano: An Elegy for the Earth (G.T.Thompson, 2023).

Charlotte Parkin

Head of Marketing & Sub Editor for On Landscape. Dabble in digital photography, open water swimmer, cooking buff & yogi.

Early Background

For me, I was almost never without a camera in my hand. When I was two or three years old, my favorite toy was my father’s broken camera. When I was eleven, I received a camera, a Kodak Brownie Starmatic, as a Christmas gift, which became my constant companion. My family, friends, and pets graciously endured the frequent crackling of the startingly bright flashbulbs—and I had my first (and only) New York exhibition as part of the National Scholastic Awards when I was thirteen. Soon after, my father built me a small darkroom in the basement, and my future direction in life was firmly established.

I loved light and, as a child, would often stand in our backyard relishing the constant and palpable presence of the light of the world. Light itself became the subject of many of my early photographs, and I sensed the connection as a child between the light of the world and the light-giving energy within myself. The experience was quite remarkable, and I marvelled at this connection through a camera lens.

Then, in 1970, as a young photojournalist student at Kent State University in Ohio, near my hometown of Akron, I witnessed and documented the events surrounding the deaths of four students from National Guardsmen’s bullets at Kent State.

This is the ultimate paradox of the creative process; that the deeper we strive to penetrate within ourselves, the more we reach a common ground of shared human concerns. I am now interested in the evocative power of the photographic medium to reveal the clash of cultural values evident in the modern world — to raise our collective level of awareness of the contradictions inherent in ourselves and, by extension, in the world itself.

Seeking new directions in my life and work after Kent State, I contacted Minor White, one of the most influential photographers of the post-War era and became his student, and eventually a friend and assistant. Minor taught the art of seeing as an expression of human consciousness. He embodied and taught the principle of “heightened awareness,” with and without a camera, as a means of transforming one’s own perceptions and making a difference in the world. Minor’s thought and friendship touched me deeply and helped shape my direction as an artist.

Stephen Shore, former student of Minor White and a recipient of a MoMA retrospective several years ago, writes about White’s influence on his photographic work: “One thing I’ve always been interested in is what the world looks like when you’re in a state of heightened awareness. Those moments which I think everyone has where experience feels more tangible, where experience feels more vivid… and as you walk down the street with that frame of mind, relationships begin to stand out.”

To make all my decisions conscious, I started filling the pictures with attention.

After working with Minor, the life of the land—its reality and metaphors—became the subject of my work and, for decades I worked mostly with a 5X7 view camera. This changed around the turn of the millennium as digital technology drastically evolved and I now have a mostly digital workflow, including the scanning of my archive of negatives.

Along the way, I received a BFA from School of the Museum of Fine Arts/Tufts University in Boston and an MFA from Rhode Island School of Design. I soon started teaching art on a college level and regularly teach classes and workshops in photography, the creative process, visual perception, and digital imaging. Ever since the late 70s, teaching has held a central place in my creative practice for many reasons.

Another aspect of my life that bears mentioning is the complete loss of my right dominant eye to an impact injury while chopping wood when I was thirty-three years old. Fearing the loss of my capacity to see and photograph, and with all hope to the contrary, this blow helped to awaken my own awareness. Losing an eye and facing the resulting need to learn to see again, this time as an adult, assisted the growth and development of my perceptual capacities—and helped me better understand the function and process of sight. Above all, I learned to not take vision for granted. It was a profound learning experience, one that continues to this day. The experience was traumatic and painful—like nothing else I have ever experienced—and a great privilege.

Oceano

The question of whether landscape photographers have the responsibility to reveal the beauty of nature is a complicated one. I would say it all depends on one’s motivation and having sufficient discipline and enough of an awareness of the visual language to avoid the easy clichés and tired tropes found in so much popular photography that serves nothing expect perhaps the photographer’s Instagram feed and their own ego. I think we have a mandate to go deeper and reflect what I would call the many paradoxes of nature and the contemporary world’s treatment of the environment. In my own recent photographic work, I have become interested in two oppositional themes.

Many of my images from the past several decades explore the multiple threats to the land and ocean resources of Hawai‘i, where I lived for the past thirty two years. The intense beauty and spiritual power of the land and ocean are tempered by the ongoing forces of colonization, overdevelopment, and climate change that have left indelible marks on the land and soul of the people. Monster storms, king tides, coastal development and erosion, storm surges, military land use, and toxic agriculture have made the islands of Hawai‘i one of the most fragile and threatened ecosystems in the United States and the Pacific region.

The other ongoing interest in my work revolves around consciousness itself. Can the arts express the powerful dynamics of awakening to heightened awareness, where, through attention, we see the true nature of things? I feel capable now, for the first time in my life, to address these kinds of questions as an artist. I resonate with David Bowie’s observation that “aging is an extraordinary process where you become the person you always should have been.” In photographing the land, I am interested in how the ephemeral, ever changing landscape expresses perennial truth and reflects the many correlations between nature and the dynamics of the inner world.

I first discovered the Oceano Dunes during a short visit while on a book tour down the California coast for my book Zen Camera: Creative Awakening with a Daily Practice in Photography.

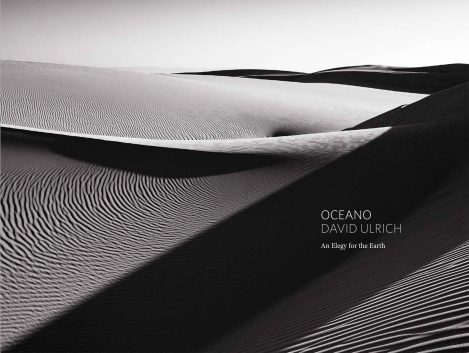

What attracted my eye and camera were the powerful metaphoric forms created by the wind-blown sand and the purity of the light contrasted with the deep shadows and blackness that interrupted the radiant whiteness of the terrain. A reverant stillness that I felt in the land itself was also disturbed by the buzzing of the motorized vehicles, like a disturbing pack of flies that will just not go away. The metaphor was immediately clear: a radiant purity of life tempered by the forces of darkness and human contamination. The place was a microcosm of what is happening to the earth world-wide and that is what I wanted to evoke through the camera lens. My early photographs from Oceano reflect the sensuous interaction between the sharp light and the blackness of shadowy forms.

My early photographs from Oceano reflect the sensuous interaction between the sharp light and the blackness of shadowy forms.

The Oceano Dunes extend approximately 18 miles along the Central California coast from Pismo Beach to Guadalupe. Divided into a smaller natural preserve and a larger area devoted to vehicular recreation with dune buggies and motorbikes, the dunes are a stunning example of how the land is equally shaped by human and natural influence. My partner and I visited the area over a period of two years, exploring the parts of the dune complex where walking was safe and free from motorized vehicles cresting the dunes at high speeds.

The photography was difficult due to the wind, blowing sand, and the need to trek up and down on the shifting, sandy ground of many dunes that were up to five hundred feet high. Initially, I used a tripod, but that was rapidly abandoned due to the additional weight on the uphill climbs. I photographed both in B&W and color, though the photographs in the body of the sequence in the book are exclusively B&W to further the metaphoric content. The book designer, David Skolkin, found a brilliant and effective solution for including a spread of color images by creating a fold-out set of pages in the latter portion of the book. And the printer of the book, Pristone Printing, Ltd, in Singapore, did a marvellous job in matching my test prints and doing several sets of printed proofs to insure fidelity and quality in the printed images.

Photographic Activism

In the 1990s, I was part of a team of three photographers, a book designer, and an archaeologist commissioned to work with Hawaiian cultural leaders and produce a collaborative book and travelling exhibition on the Hawaiian island of Kaho‘olawe, the smallest of the eight principal Hawaiian islands. Located on the leeward side of Maui, Kaho‘olawe is uninhabited and devoid of a permanent water source. It is the only island named after a god and is sacred to the Hawaiian people, with over a thousand archeological sites: heiau’s (stone temples), fishing shrines, petroglyphs, house platforms and astro-archeological observatories. Kaho‘olawe is a national treasure, with the entire island being included on the National Register of Historic Places.

Tragically, Kaho‘olawe was used as a target range for ordnance training (shelling and bombing) and military exercises by the US military for fifty years, from just after Pearl Harbor in 1941 until 1991. The project involved numerous trips to the island and took place between 1993 – 1997, soon after the bombing ceased. The exhibition traveled widely and closed at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington D.C. in 2002. Many congressional legislators were invited to witness the book and/or the Washington exhibition and congress appropriated 400 million in funds to provide a partial clean-up of the island. While there is no direct evidence to support this, we like to think that the book and exhibition helped to move the needle in increasing public awareness, especially among legislators, of the inherent sacredness and military devastation of the island.

Among the three photographers, I focused chiefly on the land and sacred sites as well as what was left of the sizeable military footprint on the landscape. The other photographers addressed the people, current conditions of the island, and the ocean resources. Several of my images from the project can be found here on my website.

Ever since Kaho‘olawe, I have been interested in how photography can awaken people’s minds and expand both individual and social consciousness about the environment. Photographers like Ansel Adams provide a shining example of making images that reflect the power of nature and that highlight the need for conversation and care for the environment. Of course, Ansel Adams was as much a conservationist as he was a photographer. He was one of the founders of the Sierra Club and advised several US Presidents on environmental policy, and his stunning photographs bear witness to his deep connections to the natural world.

As an artist, I have spent many years—decades even—protesting human injustice to the environment and have worked often from a state of outrage. Many current photography projects by numerous photographers address environmental change in a sobering new category known as the “apocalyptic sublime,” a termed coined by Morton D. Paley in a book published by Yale University Press. Maybe this type of work is necessary to affect positive change in the world… or maybe not.

But we also must ask, why? What are we working for? What kind of better world can we imagine and work towards? Can we take stock of our collective ideals as well as our current ills? Several years ago, I interviewed James George, former Canadian diplomat, staunch environmentalist, and author on environmental themes.

When we got to the topic of the environment, I shared my sense of despair with him. All too often, I am confronted with my lack of awareness, my inability to be truly conscious— as well as my impotence in the face of such things as climate change and environmental degradation, and my outrage at current social conditions. At this point, Jim reminded me softly, “We work for something, not against something.” I understand this to mean, we must always keep our larger aim in mind. Personal and collective growth of being and evolution of consciousness—that can bring real change to oneself and the world—cannot take place in a state of negativity.

During an art exhibition at the 2015 United Nations climate change summit, Norwegian researchers “identified a narrow set of parameters for what makes activist art effective in altering public opinion” and engendering reflection and action. In their study, dystopian or utopian representations had no lasting effect on the viewer. Artwork that contained a hopeful message was the only genre that served to change people’s minds. “People want to be made aware of something awe-inspiring… that activates the slumbering potential in our societies.”

And in a recent Tedx talk in Seattle, photographer Chris Jordan asked the question: Can beauty save our planet?

He began, “I’m tired of hearing all the bad news exaggerated because we think that is the right thing to do. I’m tired of the term catastrophe, disaster, and especially apocalypse. The term climate apocalypse is irresponsible. … Climate change is a serious long-term problem that deserves our deepest, wisest attention.

We need, he said, “full mind intelligence backed by wisdom with appropriate level of concern.”

The photographs in Oceano—made in the age of the Anthropocene—serve as an antidote to the apocalyptic horrors of climate change, a reminder of hope, that the earth is a transient being with great capacity to heal itself if we give her the space to do so. The life of the land and our own states of being are inexorably linked. Certain places on earth reflect a deep ecological connection between the companion realities of nature and human awareness.

For the title and organization of the project, I have chosen to employ the literary form of an elegy, an extended reflection and lamentation on the earth in the twenty-first century, Samuel Taylor Coleridge writes, “Elegy is a form of poetry natural to the reflective mind.’ He explains that as the poet ‘will feel regret for the past or desire for the future, so sor¬row and love became the principal themes of the elegy.”

Sorrow and love for the earth—indeed. No better articulation exists for my regard for our dying planet and common mother.

Since my first encounter with the dunes, I was struck with their beauty, power, and their sentient, shape-shifting nature that underlies a kind of timelessness. There on the dunes, in the changing light and amidst the aeolian forms, I found expression of the wide range of human experience, my experience, from the sharpest, most physical states of being to the most refined states of consciousness and awareness. And all of this is reflected in the earth itself. We and the earth are one. We should never forget that.

The later photographs I made at Oceano for me reflect the ascendency of light. While intermixed with shadow, the light-giving, luminous nature of the land comes forward to predominate. In other words, hope prevails.

Give me silence, water, hope ….~Pablo Neruda

My most recent project is titled Silence, Water, Hope: The Colorado Plateau, and consists of photographs from the Southwestern states where the Colorado River flows.

Driving through canyons of the Colorado River near Moab, I witnessed and photographed rocks that were hundreds of million years old and noted how their imminent presence acutely confronts us with our own fragile mortality and emptiness in the face of the grand scale of existence. In light of these echoes of infinity and my fear for the future of the planet, I am reminded of the phrase, “I am a part of it, and it is a part of me.”

One of the most significant lessons I have learned over a lifetime of full and partial sight is that perception precedes thought. There is a point in perception where thought cannot follow. In art, I am interested in the edge of perception that lies underneath rational thinking. Thought is comprised of language and concept. The moment of seeing is primarily a function of non-verbal intelligence. In other words, impressions enter our being before the mind can comment. The tools necessary for expansive sight reside in the body, feelings, and unconscious mind.

Reality and metaphor intertwine in all photographs. As photographers, we must familiarize ourselves with the symbolic language of metaphor and symbol. Our images speak to the unconscious minds of the viewers as well as the engendering of conscious thought. There are many forms of injustice that photographers represent. Why are we, as artists and photographers, so reticent to approach the aims of beauty and harmony, balanced against the deep contradictions of environmental injustice? We must imagine a world that we want before it can be actualized in reality.

So, let’s imagine a world with racial and all forms of identity equality, a healthy earth, peace and justice among societies, nations, and religions—and the freedom to grow and pursue our own necessities free of intolerance and oppression.

It might be called the pursuit of happiness. Sound familiar?

Purchase details: Oceano: An Elegy for the Earth

Oceano: An Elegy for the Earth

George F. Thompson Publishing

$45.00 U.S. (trade discount)

Hardcover

148 pages with 79 duotone photographs and 8 color photographs by the author = 87

11.875" x 9.5" landscape

ISBN: 978-1-938086-92-2