Featured Photographer

Juan Tapia

Juan Tapia, farmer and photographer, has managed to stand out in the world of images by creating photographs that transcend the purely visual.

Michéla Griffith

In 2012 I paused by my local river and everything changed. I’ve moved away from what many expect photographs to be: my images deconstruct the literal and reimagine the subjective, reflecting the curiosity that water has inspired in my practice. Water has been my conduit: it has sharpened my vision, given me permission to experiment and continues to introduce me to new ways of seeing.

In this issue, we talk to Juan Tapia. His early fascination with photography was personal, rooted in childhood memories. In parallel with his career in agriculture, analogue workshops deepened his passion, and over time he gravitated away from grand landscapes to the subtle beauty of nearby environments. Influenced by art and music, his work embraces abstraction and symbolism, and he is continually seeking new ways to express and connect through visual storytelling.

Would you like to start by telling readers a little about yourself: where you grew up, what your early interests were and what you went on to do?

I was born in Roquetas de Mar, a coastal town in the province of Almería, southern Spain, in 1979. It is where I have lived all my life and where I currently reside. After completing high school, I decided to go into agriculture, working in my parents' greenhouses and growing vegetables. Like many young people, at the beginning I was not sure about my professional future; if I had known about photography earlier, I might have studied Fine Arts. In my spare time, I played various sports, as I was quite good at them. I was also passionate about fishing and puzzles. Eventually, I realised that the patience required for these activities would be an important virtue in my career in photography.

What prompted you to pick up an old camera in 2002 and register for a photography workshop? Had photography previously been important to you?

Photography was always important in my life, especially after the loss of my mother when I was only six years old. Many of these images became visual memories that helped me maintain a connection with her as if each photo captured fragments of her presence. My first photos were taken with an old Minolta film camera in the house; curiously, I photographed my own black and white photos from the family album, looking for new angles and details. It was like exploring a small intimate universe and discovering, in each frame, hidden stories and new meanings.[paid]

Thus, photography began to captivate me deeply, especially because of that mixture of uncertainty, magic and waiting that accompanies developing the film in the lab, as if each image came to life in the shadows. Shortly afterwards, I discovered that my local town council organised annual photography workshops. That brief immersion on my own awakened in me the desire to delve even deeper into this visual world, where the every day can become eternal.

‘Workshop’ doesn’t fully describe the duration and extent of your studies. What led you to continue, and how did your craft and subject matter evolve over the following years?

In those days, people still worked in analogue format. My first years of training were in workshops organised annually by the city council, which were held in parallel with other disciplines such as painting, sculpture, music and more. During this first stage, I acquired general knowledge, delving into the workings of photographic equipment and exploring historic processes, such as solarisation, cyanotype and pinhole photography, each with its own magic and artisanal character. It was then that I developed a diverse range of subject matter, although I eventually became the only student in the workshop to focus on capturing the essence of landscapes and wildlife. Perhaps my passion for nature, cultivated as a child in a Scout group, led me to gravitate towards this.

With the advent of the digital age, I thought that the workshop no longer had much to offer me and decided to leave it, convinced that my path had to take other directions. However, over time I realised that learning never stops and that there are always new details, techniques and perspectives capable of enriching my vision.

Since then, I continued to train in specialised weekend workshops with renowned nature photographers, and discovered in books and photographic talks a vast world full of inspiration. Today, after having taught many workshops with David Santiago and trained numerous students, I have returned as a student to the same workshop where I started, in search of new aesthetics and processes. My teacher is still there, at the helm, after twenty-two years, reminding me that in the art of photography, learning and unlearning is the key to assimilating new knowledge and applying it creatively.

Who (photographers, artists or individuals) or what has most inspired you, or driven you forward in your continued development as a photographer?

As a child, I was fascinated by the elegance with which words could evoke deep emotions, a fondness I inherited from my poetry-loving parents. This early connection to poetic language was a prelude to what, years later, would define my vision in photography. Over time, my artistic exploration evolved into visual poetry, a quest to capture the essence of a moment or scene as evocatively as a poem would.

Throughout my photographic development, I have found inspiration from numerous photographers, but a few marked a turning point in my creative process. The work of Isabel Díez, for example, taught me to fragment the landscape, a technique that allows me to discover more intimate and personal perspectives in each natural environment. Similarly, Antonio Camoyán's series on the Rio Tinto opened up the world of abstraction for me, giving me a new language to express myself visually. On the other hand, the symbolism of Chema Madoz inspires me deeply. Although he does not work with themes from nature, his way of playing with everyday objects and giving them alternative meanings has taught me to see images as an invitation to reinterpret reality.

In painting, I find constant inspiration in the figure of Pablo Picasso. His tireless ability to reinvent himself, exploring diverse styles and taking risks at every stage of his career, is an example of boldness and authenticity. His work reminds me that artistic growth is a journey that never stops and that every change, however uncertain, can be the bridge to a more genuine and profound expression.

Tell us a little more about your local area and the places that you are drawn back to?

In the early years of my career as a nature photographer, I was attracted by the possibility of travelling to remote and imposing locations, seeking out expansive landscapes that, in themselves, provided visually stunning scenes. Over time, however, that idea began to fade, and I began to notice a certain dependence on scenery.

Over the years, I have come to greatly appreciate so-called ‘proximity photography’, which invites me to find beauty in nearby environments. In my case, the Tabernas desert and Cabo de Gata, two natural treasures barely an hour away from my home, have become recurring backdrops for my work. Likewise, the greenhouses, which form part of my everyday environment, have provided me with some of the most significant images of my professional career. These experiences have reaffirmed my belief that, while places are important, they are not essential.

Will you choose 2 or 3 favourite photographs from your own portfolio and tell us a little about why they are special to you, or your experience of making them?

Here are three images that have been fundamental in my photographic development. They may not be the best in my archive, but they clearly represent my personal search and artistic evolution. Each of them marks a moment of change, a significant turn in my career that redefined my understanding of photography. Through these photographs, I explored new visual languages and techniques that expanded my ability to express deep emotions and concepts. These images are ultimately milestones that remind me of the transformative power of experimentation and constant reinvention in art.

Alga

This image was taken at Cabo de Gata, shortly after a storm that had left the shore covered with seaweed, witness to the power of the sea. The landscape conveyed a profound sense of desolation, marked by the debris that the heavy swell had washed ashore. During a long walk along that small cove, my attention was captivated by a group of seaweed that, despite the adverse conditions, remained clinging to a rock, showing an impressive resilience to stay in their natural environment.

This photograph has a special meaning for me, as it was one of the first that did not arise from a visual reference or the influence of my photographic references, but was born out of pure and genuine emotion. One of the fundamental principles in the development of a personal gaze is the ability to select the stimuli that we want to transform into images, and this was one of those occasions when emotion dictated the composition.

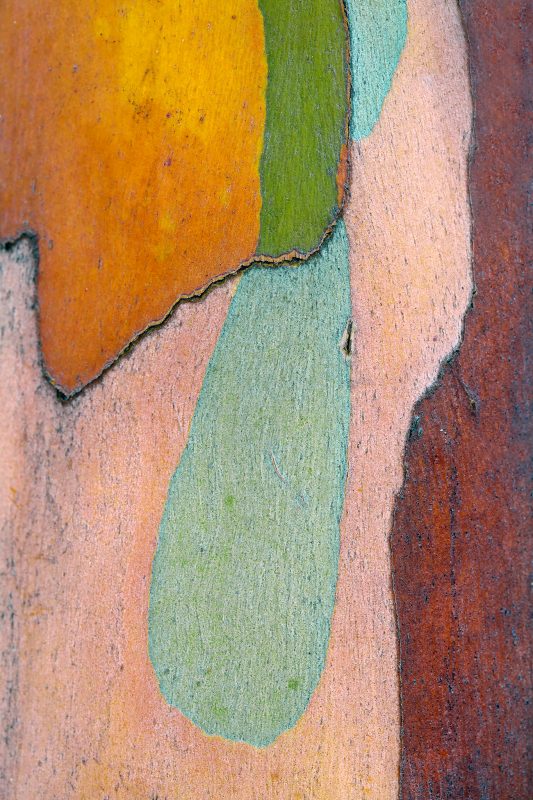

Eucalipos

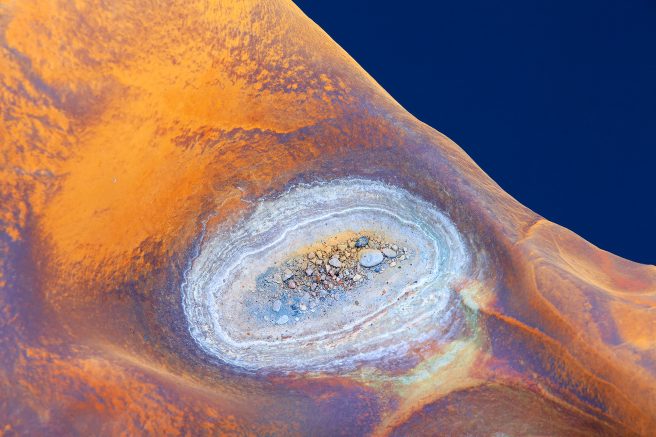

This image is part of the series entitled ‘The colour of their skin’, a collection that narrates the transformation of eucalyptus bark over time. Each photograph in this series represents a significant turn in my artistic trajectory towards the world of abstraction. This evolution began after a trip to the Tinto River with the master Antonio Camoyán, where my photographic vision underwent a profound transformation, moving towards abstraction.

Before, when walking through this forest located in the Tabernas desert, my gaze was limited to the trees as a whole. However, over time, I began to discover the hidden details that lie beneath the surface, revealing visual secrets that only emerge through new forms of representation. Thanks to this photographic work, I was able to make a name for myself in the field of nature photography.

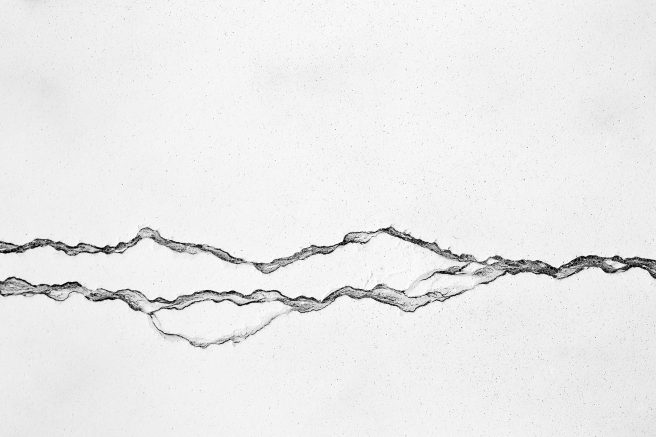

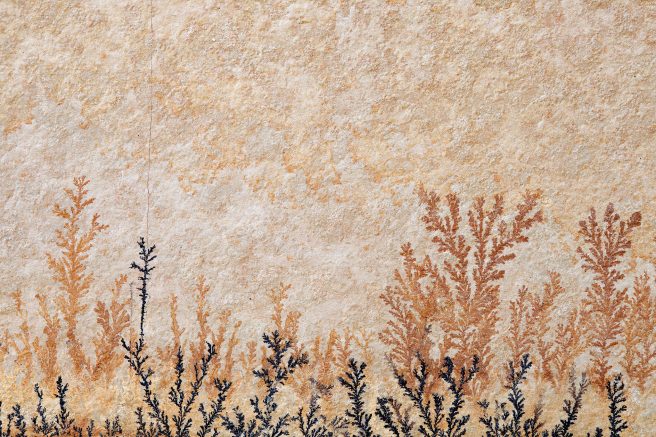

Paisaje De Cal Y Plastico

The last image I present to you is a pareidolia that I discovered on the roof of my greenhouse. After the process of bleaching its structure to reduce the temperatures affecting the plants, surprising graphics began to form on the plastic. As the days went by, I captured several of these shapes that evoked natural landscapes: a tree leaning on the bank of a river, a stream meandering over a virgin blanket of snow, or, as in this case, a snow-capped mountain range seen from a zenithal perspective.

Up to that point, I had already made numerous pareidolias in the middle of nature, but this image marked a turning point, as it was the first symbolic representation of nature outside its own environment. It was at that moment that I became truly aware of the poetic power of the image, capable of transporting us to magical places inaccessible to others.

How surprised were you to achieve success in the 2015 Wildlife Photographer of the Year awards with your image Life Comes to Art? Tell us a little about how you came to make this image.

In 2015, I was in a transitional stage between bird and landscape photography when I decided to revisit an idea I had conceived years ago: to break with the cliché of capturing a swallow flying through a window. So, I came up with the somewhat absurd idea of photographing a swallow breaking a frame to fly through it.

I found the ideal frame in my farmhouse, a painting of a rural landscape with a wide sky where I imagined the swallow would fly. This bird, common in rural areas, fitted perfectly with the theme. As the painting was somewhat deteriorated, I made a hole in the sky to allow the bird to pass through.

After a few weeks, I took the first photographs. I placed two flashes at 45 degrees to illuminate the canvas and stop the bird's flight with their partial powers. From my van, about 30 metres away, I used a remote shutter release. After eight hours of intense work, I captured hundreds of images; most with technical errors, but a few were saved, and only one was chosen for its expressive power.

Although I was initially satisfied, doubts arose as to whether the image looked too artificial. I entered it in several nature photography competitions, but only the Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition went for it. It was a surprise, as this competition values documentary style and purity of image capture. However, that edition introduced a new category called ‘Impressions’, which sought to showcase images of nature that broke clichés under a personal gaze. I think this category was tailor-made for my photography, as it fitted perfectly with what was proposed.

What difference did your win in the Impressions category make to your photography – for example, your enjoyment and confidence, the time you devote to it, or the balance between it being a hobby or something more?

This recognition marked a significant change in my photographic career and gave me greater confidence in my ideas, however absurd or unusual they might seem. The win allowed me to break free from the constraints imposed by competitions and their aesthetic policies, which often cause creative blocks. Before, I adapted my photographs to meet the requirements of the competitions, but now I focus on developing my work authentically, exploring each concept without worrying about whether or not it fits within the parameters of a competition. This creative freedom has been one of the most valuable lessons of this achievement and has allowed me to connect with my most personal vision.

In addition, being recognised in such a prestigious international competition as the Wildlife Photographer of the Year gave me unexpected visibility. This recognition transformed what seemed like a hobby into a second job that I now combine with my main activity in agriculture and has opened the doors to collaborations, exhibitions and new opportunities that I never imagined I would achieve

Can you give readers a brief insight into your set up – from photographic equipment through processing to printing? Which parts of the workflow especially interest you and where do you feel you can make the most difference to the end result?

In my photographic work, the greatest effort goes into the pre-production and production phases, where the creative process really comes to life. The observation and selection of subjects is fundamental, as it is in this pre-shooting stage that ideas emerge and the focus of each image is defined. In pre-production, I visualise the composition in my mind, identify the essential elements and decide how I want to represent them visually. I don't need extensive or complex photographic equipment; many of my photos could be captured with any camera because the value is in the vision, not the technology.

The production phase is where the camera becomes an extension of my perception, allowing me to apply techniques and composition to realise what I have conceptualised. My training in the analogue era taught me that the moment of the shot is where a photograph is truly complete: each capture is the result of careful planning and clear focus. Although digital development is part of this phase, I don't give it too much importance, limiting myself to basic adjustments of brightness, contrast and colour, similar to what we did in analogue labs. I do not seek to alter the image but to polish it and highlight the key elements that were already present in the capture.

Finally, the post-production phase also involves an additional effort, as I seek to give maximum visibility to my work through social networks, exhibitions and books. For me, the art of photography is a language to communicate and connect with others. To create images just for oneself, without sharing them, would be to lose the true purpose of art: the transmission of a message or emotion.

In addition to your love of the natural world, you have said that you try to bring painting and music into your photography. Can you elaborate on this are they influences for what you are drawn to, how you compose your images, or do you also paint or play an instrument?

Although I have never painted, art history is something I am passionate about. Photography and painting have shared key historical moments, influencing each other and shaping their respective evolutions. I find the artistic avant-gardes of the 20th century an endless source of inspiration and learning, as these currents challenged norms and opened doors to new ways of seeing and interpreting reality, allowing the every day to be represented through figurative and abstract approaches.

This pictorial influence is reflected in my photography through images that evoke different artistic styles. From impressionistic compositions to abstract and surrealistic approaches, each style brings a visual richness that enriches the viewer's perception and gives depth to the photographic representation. For me, knowing the history of art is a fundamental tool to develop a broader and more diverse view, always in search of new ways of seeing.

As for music, although I don't play an instrument, I am captivated by the serene melodies of the violin and the piano, which convey calm and uplift me. I try to capture that same enveloping and expressive atmosphere in my images, a mixture of deep peace and intimacy, although sometimes I don't know if I succeed completely. Studying the creative process of musicians is also very inspiring for me; their approaches and constant innovations throughout their careers show me that there is always room for reinvention and growth in art.

You have talked about transmitting sensations… trying to find something new each time you go out. You seem especially drawn to abstraction, and enjoy experimenting. What now motivates you?

In my early days, I conceived photography mainly as a tool to capture the beauty of environments, plants or animals. However, over time, I began to reflect on its expressive potential. This evolution arises from the understanding that photography is a means of communication between the author and the viewer, in which each shot can generate different interpretations in the beholder. When I talk about looking for something new in each outing, I am referring to that constant need to find new forms of visual communication that allow me to maintain my motivation in this world and continue to grow.

A key moment in my career was the discovery of the world of abstraction, which opened the doors to new interpretations through shapes, colours and textures. This kind of image invites the viewer to a state of search, where he is torn between what he sees and what those forms suggest to him. I am currently very interested in symbolism, an area that challenges and fascinates me in equal parts. The creation of a universe of meaning that departs from its origin, that defies expectations and proposes new visual readings, is a process that I find extremely stimulating and complex.

Exhibitions and books suggest that it is important to you that other people see your photographs in print. How do you choose to print and present your work and looking ahead do you have a preference for one over the other (exhibitions or books)?

At present, I do not have a definite preference between exhibitions and books, as I consider both forms of presentation to be valuable, albeit limited in scope. The digital environment, with its ability to reach a global audience instantaneously, is undeniably crucial in the contemporary world. Platforms such as social media allow us to share our work more widely and quickly than any physical exhibition or book, which generates a greater impact in terms of visibility.

That said, I also recognise the unique value of more traditional experiences, such as physical exhibitions and printed books. Presenting a work in an exhibition space allows for a more intimate and direct interaction with the viewer, creating a special bond between the work and the audience. Books, on the other hand, offer a lasting, tangible record that allows for a slow and thoughtful appreciation of the work.

In the end, regardless of the format, for me, the essential thing is the interaction with the viewer. Photographs become meaningful when they are seen and generate reactions in those who look at them. While digital platforms broaden our reach, physical exhibitions and books offer a depth that is also important in any artist's career. I believe that both formats complement each other, and I will continue to explore them as the project requires.

What do you feel you’ve gained through photography?

Photography has been my main ally in the exploration of my inner world, a confidant with whom I have shared my tastes, insecurities and concerns openly. I consider myself a naturally introverted and reserved person; I often find it difficult to express what is inside me. However, through photography I have found an authentic and sincere way to channel my emotions, sensations and ideas in a way that would be difficult to express in everyday life without the mediation of the camera.

Photography has taught me to pay attention to small details and to look beyond superficial appearances. In the same way that in life the most valuable essences are often found in the most inconspicuous details, I have learned that not everything is what it seems at first glance, but that the true essence is in how we interpret what we observe. This approach has not only transformed my view of the world, but has also enriched my daily life with valuable lessons about perception and interpretation of reality.

Do you have any particular projects or ambitions for the future, or themes that you would like to explore further?

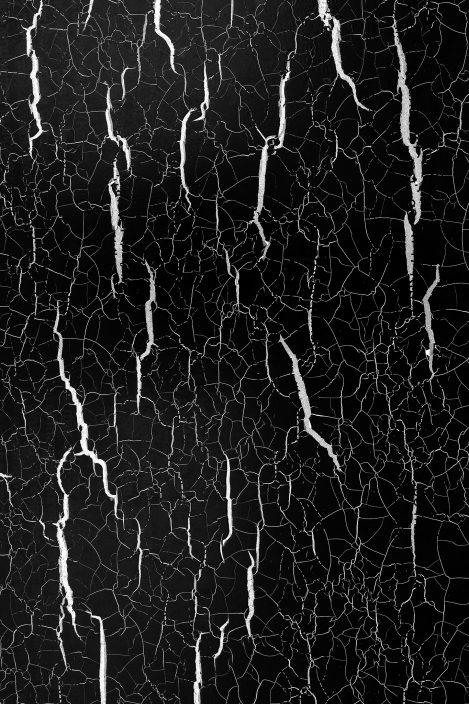

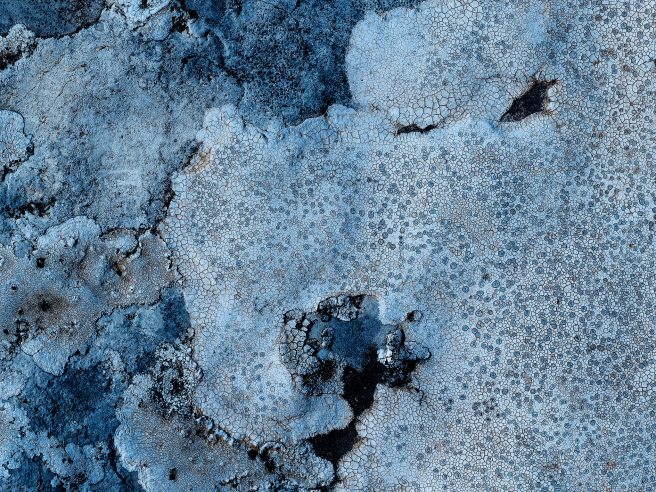

I am currently developing a personal photographic project that explores the relationship between my passion for nature and my working environment, the greenhouse. Many of the images accompanying this interview are part of this work in progress, which still requires considerable development, but I am excited about the possibility of it becoming a work that innovatively reflects my artistic evolution. Like many photographers, I aspire to publish a book compiling my work, and in this project I have found a theme with which I feel deeply identified. Through it, I wish to highlight the importance of looking closely at the immediate environment, demonstrating through my images that it is not necessary to travel far to discover beauty and establish a meaningful connection with the viewer.

For me, there is nothing more personal than intertwining my daily work in the greenhouse with my photographic passion, as each image becomes a bridge that connects these two worlds. My project is also an invitation to reconsider everyday spaces to see how work and creativity can feed each other to shape a unique visual universe.

If you had to take a break from all things photographic for a week, what would you end up doing?

Sometimes I feel the need to completely disconnect from everything related to photography. In fact, during my summer holidays I usually spend almost a month without thinking about it. With the current pace, between workshops, conferences, articles, interviews and other training activities, I find it essential to take these breaks to recharge my batteries and keep my balance. From a creative point of view, I also find that these breaks are necessary to disconnect and then reconnect with a renewed perspective.

Disconnecting allows me to return to photography with fresh eyes, appreciating the creative process in a fuller and more open way. Also, by exploring other disciplines and feeding my curiosity outside of the camera, I find inspiration in unexpected places, which adds depth and unique nuances to my images. Each time I return, I feel I have something new to contribute, a vision that would not have emerged without these moments of pause. These reflective spaces not only keep my work fresh, but also help me remember why I started in photography and rediscover the pleasure of capturing moments that reflect my artistic identity.

And finally, is there someone whose photography you enjoy – perhaps someone that we may not have come across – and whose work you think we should feature in a future issue? They can be amateur or professional.

I would like to recommend two outstanding photographers from my homeland whose work I think deserves to be featured in a future issue. I would not be surprised if they have already published with you.

As for established authors, I would like to highlight Isabel Díez, who has been my main source of inspiration throughout my artistic development. Her work, mainly focused on coastal landscapes, stands out for the enormous sensitivity with which she captures the smallest details, transmitting calm, strength and mystery.

In the field of emerging artists, I would recommend César Llaneza. His work is also characterised by a meticulous attention to close framing, as well as a special elegance in the treatment of colour and the emotionality that his motifs evoke. Llaneza's images possess a unique vitality that makes them truly captivating.

Thank you, Juan. It’s going to be fascinating to see how your intermingling of photography with your working environment continues to evolve.

You can see more of Juan’s photography on his website. You’ll also find him on Facebook and Instagram.

We have previously featured the two photographers that Juan has suggested, and you can read these interviews by following the links below.

[/s2If]