Rhythm, Light and Composition

Keith Beven

Keith Beven is Emeritus Professor of Hydrology at Lancaster University where he has worked for over 30 years. He has published many academic papers and books on the study and computer modelling of hydrological processes. Since the 1990s he has used mostly 120 film cameras, from 6x6 to 6x17, and more recently Fuji X cameras when travelling light. He has recently produced a second book of images of water called “Panta Rhei – Everything Flows” in support of the charity WaterAid that can be ordered from his website.

Art is how we decorate space; Music is how we decorate time.~ Jean Michel Basquiat

I was recently at a jazz concert by the piano trio PrismE from Geneva who played a piece called Bokeh (which required an explanation of what was meant by bokeh from the bassist Stéphane Fisch1). This made me wonder about the links that might be found between photography and jazz. There are, of course, many celebrated photographs of jazz musicians, taken by many celebrated jazz photographers such as W Eugene Smith, Gjon Mili, William Gottlieb, Herman Leonard, Chuck Stewart, Lee Tanner, Roy DeCarava, and Michael Howard. Many of those photographs were taken during rehearsals and concerts but one of the most famous is that taken by Art Kane and titled “A great day in Harlem”, featuring 57 different jazz musicians from Art Blakey to Count Basie (as well as a fine collection of children).

Searching for more information about photography and jazz, there is some about artists who have been influenced by jazz, particularly in the early to mid-20th century, such as Otto Dix, Piet Mondrian, Romare Beardon, Stuart Davis, and Jackson Pollock, but very little to be found about photographers influenced in their style by jazz, or jazz compositions influenced by photographs. There have certainly been jazz musicians (as well as more classical composers) influenced by nature, including an interesting double album by the Azerbaijani saxophonist Rain Sutanov with the title Influenced by Nature (I was prompted to find a copy). Back in the 1950s the multi-instrumentalist Yosuf Lateff had a track titled Jazz and the Sounds of Nature (rather freeform in nature and seemingly mostly inspired by birdsong).

So nature and landscape have, to some extent, influenced jazz, but what is missing here is any apparent influence of jazz on landscape photography. That seems a little strange since surely ALL landscape photographers love some type of jazz4? Many photographers are also musicians, perhaps most famously, Ansel Adams again and his early ambition to be a concert pianist. But that is in the classical tradition and it is perhaps easier to see some analogy between classical music of the romantic period and classical landscape photography. In fact, the only reference to jazz musicians being influenced by photographs that I have been able to find is the Dave Brubeck 2009 orchestral work, composed with his son Chris, and called: “Ansel Adams: America” (but it has to be said that the piece is indeed much more classical in style and does not seem to show much jazz influence)5.

Jazz is commonly defined as an improvisational musical form, characterised by complex syncopated rhythms, deliberate deviations of pitch and timbre, dissonances and polyphonic ensemble playing. It is certainly possible therefore to draw analogies with photography. The jazz photographer Nick Clayton has written in an article about Photography and Music,

I tend to photograph like a jazz musician. I don’t control a scene or situation, I adapt to it and search for themes in the apparent chaos of it all. I would define mastery of both music and photography as the ability to find meaning where others may not, and reveal it to an audience. That’s the goal anyway.5

That could equally be applied to revealing things in the landscape too. Others have referred to the idea of both music and photography containing rhythm, both containing light and dark, or positive and negative, and to the “subject” being the focus of either piece or image. There is also the analogy between playing notes “in the pocket” and the “decisive moment”, and between the choices made in the notes to start and end a piece with the framing of an image. A comment following that same article also noted:

It’s interesting how so many words can be applied to both music and photography…..Composition, Tone, Balance, Timing, Culture, Harmony, Subject, Narrative, Dedication, Artistry, Technical, Analogue, Digital, Retro, Avant-garde, Experimental, Expressive, Transcendent, Contrast, Vibrant, Sombre, Darkness, Lightness…6

While a Tim Parkin article from 2011 suggested:

“Can I create a more pleasing final result through the inclusion of dissonance than in the straightforward application of beauty?”. To me, I would say yes - it’s the dissonances in a picture that keep your eye moving around, the inclusion of ‘tensions’ that keep a viewer looking. (This could be taken to another step when putting together a series of photographs such as in an exhibition or book). 7

But when it comes down to jazz performance:

We just have to live with these labels... I mean, what we're doing, if you have to call it something... I guess it's jazz, but it's not what jazz was……It's nothing we're fighting for, though. It's just what we play—and we play how we feel. ~ Esbjörn Svensson, 20048

So there are analogies (admittedly rather simplistic), including trying to take images to reflect how we feel at the time, but there is the very obvious difference that music exists over an extended period of time (from the tens of seconds of the “Eight pieces for piano” of György Kurtág to the 639 year composition of John Cage called “As slow as possible”) with only limited extent in space, while photography is a static representation of space that refers to a particular choice of moment in time.

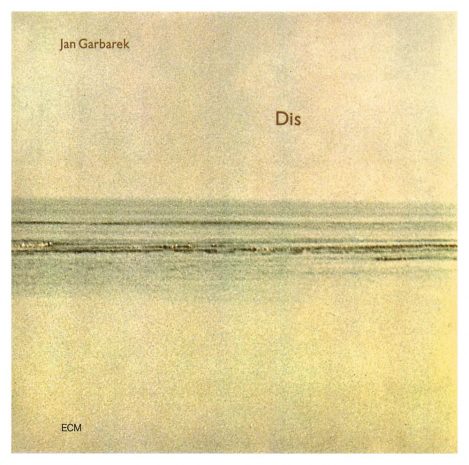

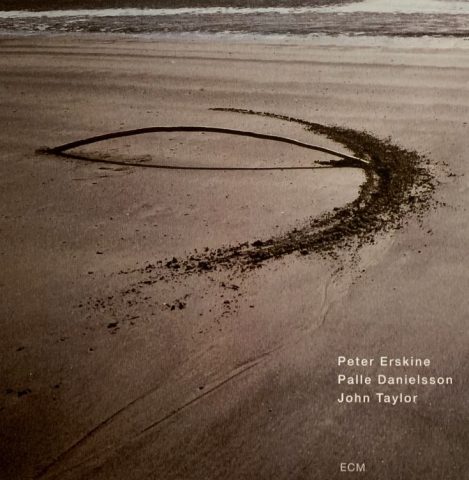

That is certainly possible – improvisations are necessary for intentional camera movements or double exposure techniques, for example. There are also successful landscape photographs that can show interacting rhythms or dissonances (there are many examples in images of trees or waves for example). And most of us will sometimes make use of extreme wide angle or telephoto lenses to produce creative deviations in ways that the eye would not normally see. In emotional terms too, we might see in a minimalist image the equivalent of the jazz influenced pieces of Erik Satie (which have been reworked by many jazz musicians since) or the quieter pieces of Miles Davies from the period of Kind of Blue or In a Silent Way. Another example that you might already be aware of would be the minimalist images chosen as the artwork for many of the jazz albums issued by the ECM label10 by Manfred Eicher working with the designers Barbara Wojirsch and Dieter Rehm11.

Perhaps more interesting, however, might be to explore any landscape images that could be more equivalent to the Miles Davis double album of Bitches’ Brew from 1970. There is a certain difficulty there, of course, in that Miles Davis and his musicians start with a blank sheet. The intense creativity of those albums is developed in rehearsal over time (even if many jazz tracks are recorded as one improvised take).

As photographers we largely work alone and depend on what nature puts before us in terms of subject and light. We may also have our individual skills and histories, but our creative control over nature is limited to framing and exposure and waiting for the right moment. Our experience might help us to be in the right place with the right equipment at the right time, but to be jazz-like in our images we are limited to choosing the right sorts of subjects.

And musical rhythm is not so different from visual rhythm. A progression of notes over a period of time is a fraternal twin to the layering of shapes, light, and dark that form a photographic image. The most successful photographs are almost always those that have a rhythm, giving the viewer’s eye a coherent path. Music is a play between ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ objects—notes and the silence between. I believe it was Debussy who said that “Music is the space between the notes”; and negative space plays an equally important role in composing (aha) a photograph ~ Leah Damgaard-Hansen12

Guy Tal, in the On Landscape article that refers most to Jazz also suggests that there is more to the process when it comes to producing a print. He refers to the Ansel Adams quotation (rather remarkably from an interview in Playboy magazine) which in full reads:

Yes, in the sense that the negative is like the composer’s score. Then, using that musical analogy, the print is the performance. ~ Ansel Adams, 1983

But then Guy comments:

I know myself to be a “jazz photographer”—a real-time improviser, not a disciplined performer of pre-written scores (not even ones I wrote myself in other times). When I set to make a print for myself or for an exhibition (i.e., not a print purchased by a customer expecting it to match the appearance of a digital version or of a previous “performance”), I consider it as an opportunity to make a new creation—new “visual music,” not necessarily aiming to re-perform my original visualization by some singular, fixed, “right” interpretation. Each “performance” is for me a chance to make something new and original. ~ Guy Tal, 202213

He also contrasts that with the many photographers who, rather than producing a new performance, are happy to only repeat the images they have seen produced by the original artist.

When it comes to such separation of roles between composer and performer, photography lags considerably behind music. Most photographers and viewers of photography make no distinction between composer and performer, assuming implicitly that they are always the same person, despite this often not being the case. In landscape photography, especially, the case is almost always the opposite: few original composers make meaningful, novel creations, which are then performed repeatedly by many others (who usually have no qualms about claiming the entire production—composition, performance, and all, as their own). ~ Guy Tal, 2022

My own preferred subject for photographic performance, as has been seen in many of my previous articles in On Landscape, is water14. Water can be musical in the sense of having rapidly changing dynamic rhythms and sounds over time. It inspires many landscape photographers both in its forms (of waterfalls, rapids, waves and gyres) and its interaction with light (in reflections, caustics, landpools and skypools)15.

Music is again somewhat different here. Even when only sampling online fragments of 30 seconds, it takes time. Listening to whole pieces and albums requires a greater commitment of time. Indeed, it sometimes requires repeated listenings to appreciate a piece, particularly for more difficult pieces (some of Charlie Parker, or the younger Sonny Rollins, or the string quartets of Bartok come to mind).

But we should not perhaps push this analogy too far. Creating good jazz is really difficult, requiring both a high degree of talent and long hours of practice and experience in making choices in working with other musicians. Creating a good image also requires some combination of talent, practice and experience in the choices we make, but I am not sure we can claim to reach the same level of difficulty. We frame and we click. We bring our experience and emotions to bear in doing so, and we may have to make an effort (or get up early) to be in the right place at the right time, but in the end we frame and we click. That is our act of creation. If you can see a jazz riff in the results, then perhaps the best that we can hope for might be a quiet smile of recognition (or else just a swipe on to the next one …..).

References

- You might remember my own definition from the Devil’s Dictionary: Bokeh [n]: A result of using expensive lenses wide open to distract from an uninteresting main subject in an image. See https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2021/03/devils-dictionary-photography/

- Just search on “jazz and nature” on YouTube and then go relax!

- Ok, so some Free Jazz sax solos from the 1960s are really rather difficult to love!

- See https://www.anseladamsamerica.com/about-the-work (with extracts) and https://www.npr.org/2009/04/02/102656153/dave-brubeck-composing-ansel-adams

- See https://casualphotophile.com/2021/04/05/music-and-photography/

- A comment by David W. on the article by Nick Clayton in 5. The article also has some other thoughtful comments.

- Tim started to explore the links between musicians and photographers in his 2011 article https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2011/05/photography-and-music/

- From an interview with All About Jazz in 2004, https://www.allaboutjazz.com/esbjorn-svensson-what-jazz-is-not-was-esbjorn-svensson-by-joshua-weiner

- See, for example, the On Landscape article by Cheryl Hamer and Glenya Garnett at https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2019/04/multiple-exposure-layers-textures/

- These have their own Flickr site at https://www.flickr.com/groups/ecmrecordcoverphotographs/

- See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barbara_Wojirsch and https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dieter_Rehm_(Fotokünstler) (in German). A book of their album covers called “Sleeves of Desire” was published by Lars Müller in 1996 (ISBN: 978-1568980645 but now out of print)

- Again from https://casualphotophile.com/2021/04/05/music-and-photography/

- See https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2022/05/classical-photographers-jazz-photographers/

- As in the two books The Still Dynamic and Panta Rhei. The first is still available in PDF format; just a few hard copies are left of the second – see https://www.mallerstangmagic.co.uk/?post_type=product. All the images shown in this article were taken after the books were produced.

- See, for example, https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2017/04/the-science-and-art-of-hydrology/ https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2019/01/physics-of-caustic-light-in-water/ and more recently https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2023/11/a-little-piece-of-eden/