Part One

Douglas Butler

Doug is a legal aid attorney living with his wife, Jen, in the Pioneer Valley of Western Massachusetts where he enjoys exploring the region, making images and writing.

“[C]reativity is inherently . . . tied up with process, you cannot escape it. ~Joe Cornish

“Form: manner or style of performing or accomplishing according to recognised standards of technique ~Miriam-Webster Dictionary

The Pioneer Valley consists of the three counties through which the Connecticut River—the longest river in New England—flows down Western Massachusetts from Vermont to Connecticut. The “Pioneer Valley” was dubbed by nameless travel writers a century ago to draw tourists into the area, an invention that adds a deceptive veneer to an area suffused with over 6,000 years of human history. Accounting for its fertile soils and arboretum feel, the Pioneer Valley is situated on a former seabed snugged in an ancient rift valley, sat between the once rugged Berkshire Mountains and an unnamed ridge of peaks to the east. It is in this rather narrow former ocean floor turned terrarium that I, nearly exclusively, make images, and in which I have come to hope for and rely on the unexpected in doing so. Making images on an ocean floor turned veritable botanical garden, where over 6,000 years of human experience has been expunged and from a name contrived by forgotten advertising men, it seems fitting that a random quote from surrealist novelist Tom Robbins has provided a key for unlocking a more considered approach to my image making.

It is an approach that I have applied for some time and that has allowed me to start pursuing, as acclaimed American photographer Ralph Gibson puts it, a “visual signature” and to evolve the artistic outcomes I seek (and the methods by which I achieve those outcomes). This renewed approach — a roadmap of sorts — could lead anyone to artistic discovery in expressive image-making, and creative engagement generally. For, as Paul Strand put it, “If the photographer is not a discoverer, then he is not an artist.”

Edges

Robbins, a renowned novelist who the New York Times called “a cosmic lounge lizard,” morphed from a strict Southern Baptist upbringing, “into a moonbeam of the counterculture” of the American 1970s and beyond. Robbins seems never at a loss for the enigmatic, if not oddball, prophetic turn of phrase (or entire novel). Robbins, largely known for works that are “very weird . . . hilarious and curiously moving,” (like Jitterbug Perfume and Still Life with Woodpecker), is by all accounts a meticulous writer who “knows words the way a pool hustler knows chalk.” One of Writer’s Digest “100 Best Writers of the 20th Century”, Robbins was a well-known art critic in Seattle, Washington, before turning to novels. It was an experience that seeped into his fiction. In “Even Cowgirls Get the Blues”, Robbins gave sound instruction to the artist.

If you take any activity, any art, any discipline, any skill, take it and push it as far as it will go, push it beyond where it has ever been before, push it to the wildest edge of edges, then you force it into the realm of magic.

Enticing tuition for the artist, for who among us does not desire entry into the realm of magic? This directive to push art to the “wildest edge of edges” has given me a key to unfurling a vast expanse for exploration and discovery in my expressive image making.

When speaking of pushing any discipline beyond the “wildest edge of edges”, Robbins is speaking of form, that is, “manner or style of performing or accomplishing according to recognised standards of technique” — what Cornish calls process and what Gibson refers to as the protocols of photography. Robbins' invitation to the artist is to go beyond the limitations confronting all manner of creative engagement, including those “recognised standards of technique.” Form (process/protocols) are the parameters within which all photographers must work. However, I see form — Robbins’ form — as something broader than merely recognised standards of technique, process or protocols. Robbins’ form is virtually bespoke for each of us and encompasses aspects spanning the unique to the universal. This form concerns the methods employed by the artist, rather than the goal, the achievement, the outcome. This form is that distinct space — physical, emotional, material and metaphoric — in which we dwell as creatively engaged artists. Form includes limits, boundaries, that confine that space — frontiers for exploration, at the outer limits of which lie Robbins’ “wildest edge of edges.”

I imagine this broader version of form as the structure in which an artist must dwell and work while creatively engaged, and includes all that bounds our efforts as artists. It involves every aspect of the creative process. Among myriad others, form for the photographic artist includes our chosen genres, our subjects and thematic approaches, the choices we make with respect to our gear and processing, our decisions whether to practice predominantly near field or far field, digital or analog, our intimacy with the areas and the conditions in which we work. It also includes the thoughts, feelings, emotions, preconceptions and expectations we bring to each and every step along the process of creative engagement. Expressive image making is bound on all sides with the parameters of this more expansive version of form.

These boundaries include what is achievable with whatever gear is in one’s kit and the proficiency one has with it — our understanding of and proficiency with, so to speak, “how film sees the world,” as Ansel Adams put it. They include the ability and aptitude to access, interact and commune with desired locations and subjects, and one’s capacity to work in the conditions met. They include the personal constraints we all have as people, such as our physical condition, our locality and our ability or willingness to travel, and monetary limitations that directly shape our creative efforts. These various strictures and boundaries all apply their forces on our output as creative agents. For me, however, the ultimate importance of form lies not in its structure, per se, not the boundaries that hem us in. Rather, form’s significance lies in a purposeful, contemplative engagement with that framework and its limits, that is to say, the critical and ever-evolving relationships we build and cultivate with that space in which we are bound, in which we dwell while creatively engaged with image making.

Applying this broader interpretation of form, Robbins’ edict becomes a personal invitation to explore unreservedly that structure or space we all inhabit while engaged creatively. It is an invitation inveigling me “to push my art beyond where it has ever been before, push it to the wildest edge of edges” that limit me, and the outcomes I seek, from creative engagement. It is an invitation that perhaps should be accepted by anyone engaging with creativity, with artistic expression. Robbins’ edict is to explore the imaginative space that form provides, that space we inhabit as individual artists, such that we evolve, grow and move toward that realm of magic. To evolve as artists, we must assess and reassess our expectations from and our relationship with this comprehensive form, from the mundane to the esoteric, from form’s universal aspects applicable to all engaged in expressive image-making to those completely unique to our individual efforts.

We must do so with our gear and technology, our ability to achieve desired outcomes with the tools we employ, our intimacy with their means and their machinations’ breadth, and how those limits determine the outcomes we seek. It means examining freely and with regularity our relationships with and connections to our creative environs, whether near or far afield, before we arrive, in situ and after we depart, and how those relationships and connections enhance or inhibit our creative efforts. For those of us engaging with the landscape, it means examining and gaining an understanding of the history of a place and our history with that place as it evolves over time. It means ever striving to gain a better understanding of what we can expect when in those environs in which we choose to make images — weather, mood, atmosphere — in order to foster an ability to engage with the creative process when expectations are altogether met, when those hopes are not met or prove altogether unfounded, or when we choose to leave all expectation behind. And importantly, it means examining our relationship with ourselves, our goals and aspirations, writ large and small, and our engagement with those things I list, and others, that is, our engagement with form.

When we, as expressive image makers, examine deeply and regularly our engagement with form and our relationships with its components, no matter “how trivial or mundane” those things can seem, we open a path that can take our art “to such extremes that we illuminate its relationship to all other things . . . to that point of cosmic impact.” Once open, that path sets a bearing on the “wildest edge of edges” and perhaps a glimpse, if not entry into, that “realm of magic.” As grandiloquent as this may sound, I am convinced of the practical impact such an approach can have in the creation of meaningful images. I am not alone, it would seem. Joe Cornish has said that “photographic creativity, is also inherently a reflection of process, from both the science of photography itself and the limits on the materials, the methods and the equipment that are available to you at the time. I think that is a very important lesson to learn and is a great springboard because you can use to your advantage the limitations and the oddities that are the photographic process. . . . Process and creativity to me are intrinsically linked and importantly so.”

At this point in my development as an image maker, entering the “realm of magic” remains largely aspirational. I have, however, glimpsed Robbins’ edge of edges and the distant realm of magic beyond through my purposeful engagement with those intrinsic and important links between my creativity and the processes and protocols of expressive image making. There is no doubt there are countless image makers who regularly dwell in that realm, but there seem few, if any, external signposts pointing the way to it. However, in his approach to his writing, Robbins offered some direction as to the state of mind conducive achieving such engagement with form—a state of mind that would certainly aid any image maker in going beyond the mere glimpse and may even plunge them and their work deep into that realm of magic.

Zen Universe

Michael Dare, a screenwriter and movie producer, assisted Robbins with writing a screenplay, an adaptation of one of Robbins novels that never made it to the screen. During that period, Robbins described his writing process to Dare. In his essay How to Write Like Tom Robbins, Dare discusses that guidance in some detail. Dare explains that when Robbins starts a novel, it works like this. First he writes a sentence. Then he rewrites it again and again, examining each word, making sure of its perfection, finely honing each phrase until it reverberates with the subtle texture of the infinite. Sometimes it takes hours. Sometimes an entire day is devoted to one sentence, which gets marked on and expanded upon in every possible direction until he is satisfied. Then, and only then, does he add a period. Next, he rereads the first sentence and starts writing a second, rewriting it again and again until it shimmers. Then, and only then, does he add a period. While working on each sentence, he has no idea what the next sentence is going to be, much less the next chapter or the end of the book. All thoughts of where he is going or where he has been are banished. Each sentence is a Zen universe unto itself, and while working on it, nothing exists but the sentence. He keeps writing in such a manner until he eventually reaches a sentence which he works on like all the others. He adds a period and the book is done. No editing or revising in any way.

Or, as Robbins himself put it, “I try never to leave a sentence until it’s as good as I think I can make it.” Dare thought Robbins’ methodology was senseless for any writing project, declaring it “was no way to write a book, much less a screenplay.” Robbins himself confessed his approach was “painting myself in corners and seeing if I can get out.” If one wants to aspire to approaching and transcending “the wildest edge of edges” to gain entry into that “realm of magic,” Robbins’ approach of treating each sentence as a “Zen universe unto itself” during which “nothing exists but the sentence” seems a most suitable way to approach image making, what Thomas Joshua Cooper, among others, refers to as building an image.

As Cedric Wright, photographer and mentor to Ansel Adams, said, “[a] secret to fine results is to enjoy the most luxurious deliberations in each step of the work.” He warned that “there is a contagious contentment . . . out of which is apt to flow more of the spirit and qualities needed” to make an image. Wright determined that, “ideally, it should be as if on that one part of the work alone were focused the entire essence of a lifetime.” To strive to engage with this approach when light is fleeting and other limitations are encroaching, or when distractions abound, can reveal for us that “edge of edges” and thereby lead us to that place where creative transcendence may be glimpsed or, perhaps, even realised. Approaching any creative endeavour — except perhaps writing according to Dare — as close to this method as you can seems one route to achieving creative fulfilment, of approaching that realm of magic. While there may be some well-placed reticence to painting oneself into a corner as a routine, Robbins was on to something in his approach to writing that seems perfectly applicable to making images and our engagement with the form. It is through engagement with form that will lead us toward a comprehension and, ultimately, an intimacy with the boundaries that shape our efforts — both those that we all share and those specific to ourselves — such that we can dare to aspire to enter that realm of magic. Committing to such engagement is something that I have explored for some time, but still struggle with. The first step seems to be finding those edges of edges, wherever they may lie. As Lopate suggests, the artist must be “iintrigued by their limitations, both physical and mental [because] what one doesn’t understand, or can’t do, is as good a place as any to start investigating the borders of the self.”

Anamorphosis

From what vantage point must one be positioned to discover the boundaries of form? Where must one be stood in that unique space we each inhabit as creatively engaged artists in order to delineate those edges of form that limit us? What does it mean to and how does one explore those boundaries of form individual to our efforts as expressive image makers? For the artist there seems to be no more of a personal question, one that will elicit unique and individual responses. However, some general steps to those ends seem apparent. First, we must become proficient in those aspects of form necessary for attaining our desired artistic outcomes. We need not master every facet of the recognised standards of technique employed in photography generally, just those necessary to make the images we want to make, to attain the outcomes we desire. And once proficiency with the aspects of form applicable to our particular efforts is attained, those edges become delineated, made ready for exploration, for in order to explore edges of form we must know what they are and where they lie. We must not only know those limitations, we must become intimate with them so that we may strive to master those aspects of form that apply to our unique approach. As Gibson admits, “I have always, always, always worked within a set of specific limitations that led me to an infinitely broader horizon than I would have otherwise arrived. It’s the limitations that open the doors.”

To strive to master form, we must appreciate form as it pertains to Wright’s “luxurious deliberations” throughout image-making. Form in expressive image making is bespoke to each and every expressive image maker. Form is individual. Form is founded upon and bounded by the methodology, aptitude, attitude, psyche, aspirations, desires, gear—and more—that we each bring to our image-making and how we each choose to employ and incorporate those elements into our efforts. Form redefined here is the “[unique] manner or style of performing or accomplishing according to [more than merely those] recognised standards of technique [and includes everything that shapes those efforts].”

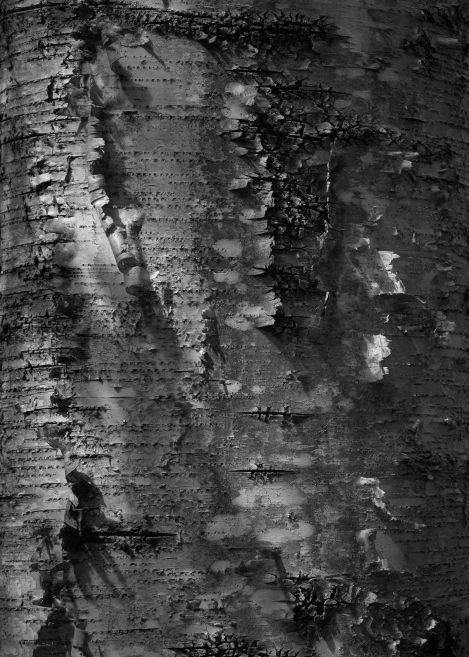

As these few examples show, the choices of a starting point for defining and applying some restriction to our work, whether temporary or permanent, are myriad and run the gamut from those that are universally applied to all image makers to those that only affect a given photographer at a given time in a given place. From the basic to the advanced form is all that binds, controls or contorts—desired or not—our efforts. Engagement with form is pervasive and unavoidable. That engagement is where we may begin to seek and, once found, push the boundaries, the edges of form. That engagement will take you from awareness to comprehension and mastery of all that limits our image-making efforts. By applying a restriction, such considered and purposeful engagement with form may allow one to find and surpass the “wildest edge of edges” of form so that we may create something that “reverberates with the subtle texture of the infinite.” Under these circumstances, setting off and exploring the edges of form seems formidable. Being one who engages with the land and landscape nearly exclusively where I live, my interactions and relationships with and connections to Place and the places I go in the Pioneer Valley of Western Massachusetts are foundational components of form that provide fertile ground for me to grow as an artist. The “restriction” of repeatedly making images in one specific location, not for days or weeks, but over the years and under varied conditions and circumstances, has afforded me a vital starting point for exploring the edges of the form within which I create images.

In Part Two, I explore my relationship with Poland Brook Wildlife Management Area, a nearby wildlife refuge, where the images accompanying this essay were made. I tell how my repeated visits over the years have enhanced my efforts to grow as an artist and offer that the same effort could help anyone grow through engagement with form.