Remembering

Tim Parkin

Amateur Photographer who plays with big cameras and film when in between digital photographs.

Joe Cornish

Professional landscape photographer.

Paul Hill

Paul Hill's early career in the 60s and early 70s moved from newspaper reporter to photojournalist. In 1974 he moved to academia, first as Lecturer and as head of Creative Photography at Trent Polytechnic.

I met John Blakemore for the first time at one of the Photographer’s Place workshops in the Peak District. The event was a reincarnation of a series of seminal residential workshops that were run in the Peak District in the 1970s and 80s which were started by Paul Hill. They offered immersive, creative courses led by influential photographers such as Thomas Joshua Cooper and, of course, John Blakemore. Over the course of the two-day workshop, John came across as a delightful combination of philosophical and slyly jocular, at once self-deprecatory but cleverly challenging in his insights.

It was during the afternoon of the second day when I got to appreciate just what a talent he was as a photographer and printer. John had collected the best of his work into an extensive portfolio of prints to take to Birmingham Library, where it was to be held in perpetuity. He said he was sure they’d be fine if we had a chance to get our hands on it before it was taken to the and so, for the remainder of the afternoon, we got our hands on some of the most beautiful examples of printing I’ve ever seen and with an in person discussion on each piece of work as it was passed around the group.

I have to thank Paul Hill for organising this event, and I also have him to thank for allowing us to publish the obituary he wrote for John, which was also published in the British Journal of Photography. I asked a couple of friends who knew John well to contribute their own personal memories of John, which will be included at the end of the article.

Paul Hill

Time plays tricks with the memory, but I think it has been about 50 years since I first saw a photograph by John Blakemore. It was a nude in long grass that I thought was made by French photographer Jeanloup Sieff, much in vogue in the 1960s and 70s and known for wide-angle images of women. Looking back, it is obvious this image was part of the transitional period between John’s documentary work, made in his home city of Coventry, and the meditative landscapes and exquisite still lifes he became renowned for in the latter decades of the 20th century and early years of this century.

When we both started work on the joint Creative Photography diploma course – he at Derby Lonsdale College of HE and me at Trent Polytechnic, Nottingham (now Derby University and Nottingham Trent University) – he sported a hipster-type beard and favoured denim jackets. I mention this because people think of John as a guru and gentle sage with long hair and beard, who always wore a fisherman’s smock and open-toed sandals. Many followed this bohemian fashion, but no one carried it off better than John.

This persona came with an ever-increasing interest in Eastern philosophy and tantric practice (his brother taught yoga in the West Country). But John was not an aloof mystic or guru. He had a sharp, acerbic wit but was also very shy. I remember him telling me that when he started teaching in Derby, he wandered the corridors at the Kedleston Road campus summoning up the courage to face his first class of students.

This will surprise those photography students and workshop attendees at my Photographers’ Place in the Peak District, who clung to his every word as he talked eloquently about his work and sensitively critiqued their photographs for hours. His introspective approach reflected a movement in British photography that sought to use the medium in a more meditative way. Nature and the landscape were the leitmotifs. Spirit of Place was replacing a moment frozen in time. However, from time to time, the black dog descended, and you would not hear from John for a while.

I knew he would emerge when asked to give a talk about his work or run a workshop – which we did, often. John was not a self-promoter. But when someone opened the door and offered a platform, he came alive and entranced his audience with deep philosophical insights and immensely useful tips on how to improve photographically. He also possessed great curiosity and an impressive intellect. An example of this came when Derby offered him a sabbatical in the late 1980s and instead of using the period to work on a new project, he enrolled on the MA Film Studies course at the University of East Anglia.

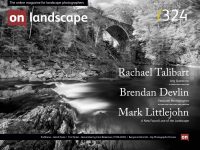

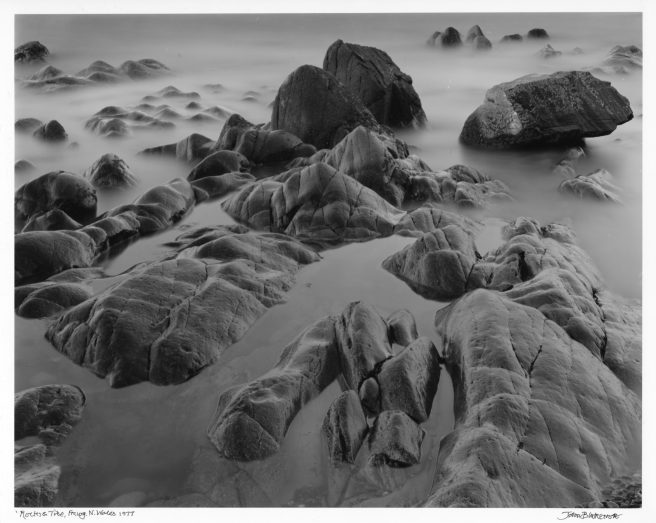

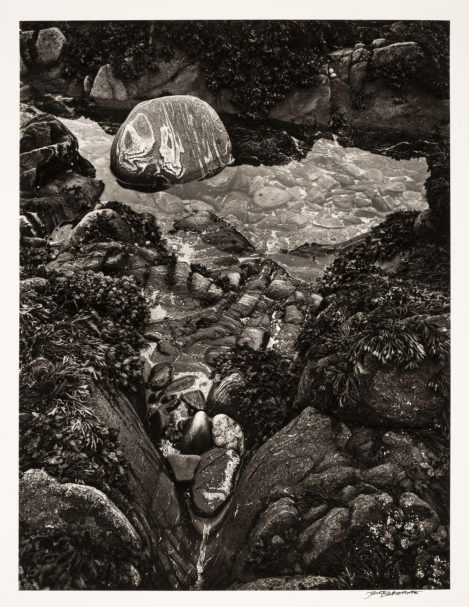

His renowned large format work surfaced following time spent in Wales in 1968, unsuccessfully running a cafe with Penny (his second wife) after the breakdown of his first marriage. Influenced by the Transcendental Movement and the work of American photographer Minor White, John returned to Wales and the Mawddach Estuary, where he used the natural world to make emotionally deep black-and-white images that were wonderfully gestural and metaphoric, about ideas, not things.

During mentally challenging periods later, he often took nature indoors and made large format photographs that beautifully chronicled the life cycle of cut tulips in and out of vases and arranged thistles and pampas grass still lifes that reminded me of Roger Fenton’s fruit and flowers prints made 140 years earlier.

Like many photographers of that postwar era, John stumbled on photography before pursuing it professionally, seeing the seminal Family of Man exhibition in the pages of Picture Post while he was doing his National Service as an RAF nurse in Libya in 1956. He recalled in John Blakemore: Photographs 1955–2010 (Dewi Lewis, 2011): “I saw photographs not as speaking of sameness but of difference. Of disparities of wealth and poverty, of war and peace.” He immediately ordered a camera and revelled in the excitement of looking through its lens.

Many see John as an artist who uses a camera, but I always think of him as a photographer who made art. This is not a semantic conceit; it defines a particular empirical practice that is camera-based, where the maker thinks and sees photographically and focuses on making the final print the event, rather than a record of what is in front of the camera. John made his landscape or still life prints with great, almost fetishistic concentration on craft and immaculateness. He was a consummate fine printer, rewarded by transmitting the sensitivities of his seeing into a tangible form.

It was an intensely personal journey as the photographs are emotional and evocative – and an escape from domestic problems and relationship difficulties. From time to time, he came to stay in my caravan in the Peak District and went out alone every day with his trusty MPP 5×4 and tripod. “To be alone in the landscape was a release, a return to the pleasures and pursuits of my childhood which had been lost to me,” he said.

John had left school at 16, going against his parents’ wishes to work on farms in Shropshire, my native county. He would talk about working with horses under the shadow of the iconic Wrekin, a hill near what is now Telford. Up until that time, he had been a city boy. He was born in 1936 into a house without books, but became an avid reader obsessed with birdwatching, drawing and painting. He was influenced by his grandfather who had been a carter (someone who transported goods by cart). Perhaps that is why he always headed for the stables when he came to visit me.

On one of those visits, he came with a handsome young man in his twenties, one of his two sons from his marriage to first wife Sheila. He had not seen him since the youngster had been a child and part of the reconciliation was visiting his photographic world. John was not a mystic in my experience, though he was mysterious. But if you want to discover this complex, gifted and generous person, you need only look at his photographs.

Joe Cornish

I was still an art student when I first came across John Blakemore’s work in the late 1970s. I still have a monograph published by the Arts Council of John’s work at the time, all of it landscape. And although other photographers have guided my own path through the years, it is no exaggeration to say that John’s influence was first, and is still the greatest. You might compare my work to his and find little, apparently, in common (colour vs black & white, wider landscapes vs intimate etc), yet John’s work inspired in me the idea that landscape photography was an artistic calling, in which personal expression was possible.

As time went by my focus became more concerned with earning a living as a working photographer, but with workshops, teaching and public speaking in recent years, I now find the lessons I learned from John’s example resonate as clearly today as the first time I saw his imagery. Only last week I found myself experimenting with a technique directly informed by prints in John’s series, Metamorphoses. I count myself lucky to have met him several times, and came to understand a little of the complexity and humanity that informs his photography. His immense contribution as photographer, printer, educator, thinker and inspiration will stand the test of time.

Kyriakos Kalorkoti

Like many others I first met John through photography, he astonished me with the depth of his insight into the psychology behind my landscape images at the time. As our friendship developed we had many wide ranging rewarding discussions: he was often amusing, always considerate, clear and itellectually sharp. These qualities shine through his writing.

On one occasion I bought a rather nice loaf of bread on the way to visit; as soon as it was unwarpped out came his camera to capture its wonder, eating could wait! I spent many happy times with a view camera in his beloved garden, too busy to notice that he was photographing me at the same time. Later on he presented me with a beautiful hand made book of the photographs with text in his characteristic handwriting, a typical generous gesture which I treasure. Many of his wonderful prints adorn the walls of our house, another treasure.

We know the day of parting will come but always hope "not yet". When it does come, the richer the friendship the deeper is the grief but the greater is the consolation from the good fortune of having had such a friend. Thank you John, my dear friend.

More about John

We were lucky to engage John to speak at our event in the Lake District. I’ve published the recording on YouTube and highly recommend watching.

If you want to find out more about John, you could also watch the piece recorded for Birmingham Library.

You can see more of our interviews and articles about John Blakemore via our tag link https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/tag/john-blakemore/.