Creating a book

Benjamin Dimmitt

Benjamin Dimmitt was born and raised on the Gulf Coast of Florida. He graduated from Eckerd College in St. Petersburg, FL where he studied photography and printmaking. He also studied printmaking at Santa Reparata Graphic Arts Centre in Florence, Italy and City and Guild Arts School in London, England. Dimmitt moved to New York City in 1976 and continued his studies in photography at both the International Center of Photography in NYC, NY and Santa Fe Photographic Workshop in Santa Fe, NM.

From 2001-2013, he held an adjunct professor position at the International Center of Photography teaching black & white photography and landscape photography.

His photography investigates interdependence, competition, survival and mortality in the natural environment. He is most curious about the places where land and water merge and landscapes with animated and layered growth that exhibit the instinct for survival and the persistence of life.

Dimmitt’s photographs have been exhibited in museums, galleries and festivals internationally and are held in multiple major museums and private collections.

In December, 2024, Benjamin’s An Unflinching Look project was nominated for the eleventh cycle of the Prix Pictet. Based in London, the Prix is widely recognized as the world’s leading prize for photography and sustainability. He lives and works in Asheville, NC.

In his first article, Benjamin took a look at the environmental issues at The Chassahowitzka National Wildlife Refuge. In 2004, he began a project, Primitive Florida, photographing landscapes in Florida that I felt were vulnerable to development, rising seas and worsening storms. In his second article he writes about the book publishing process.

My mother was an artist. She often used a camera to make studies for her paintings and drawings. Most of her work was abstract which, I believe, helped me to see the essence of what was in front of my lens. I learned to see in terms of line, shape, form and tone. She gave me a Pentax 35 mm camera for my sixteenth birthday. We had many enlightening discussions in her studio about composition, the artist’s gaze and how to locate and render what was most important in a landscape. I believe that I learned more from her than I did in many of my photography classes.

I am not alone in believing that an artist’s best work involves a subject that he or she feels most passionately about. In my case, that would be the wetlands of Florida and the forests and mountains of North Carolina, where I now live.

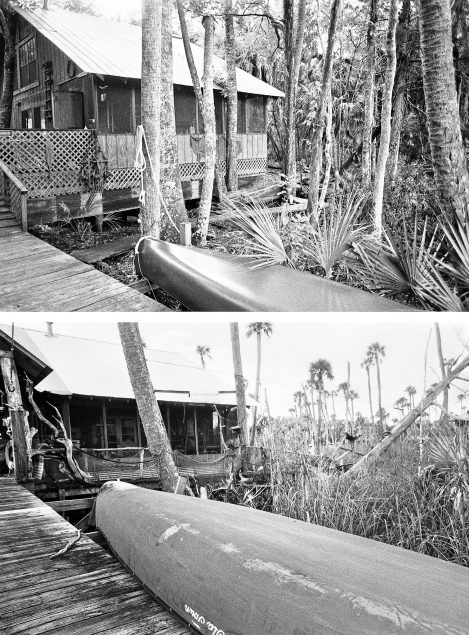

Primarily, I photograph with a medium format SLR film camera that I bought and used nearly forty years ago. The oldest photographs in the Chassahowitzka project were made using old 35 mm cameras. Very early on, I photographed from a canoe with a 35 mm camera without a tripod and without getting out of the canoe to photograph. This, of course, did not always yield optimal results. I very quickly evolved and began getting out of the canoe and into the swamp with my Hasselblad and tripod. Alligators, poisonous snakes and very soft creek bottoms all contributed to my changing my approach again. I pivoted to using high speed film (ISO 3200) when photographing from the canoe. I would get out of the canoe with my gear only in places where I could see the creek bottom and could determine that it was firm enough for me, my camera bag and my tripod.

A great many of the photographs in the project could not have been made without high speed film, careful exposure and development. I mostly use 100 and 400 speed film which allows me flexibility and yields finer grain negatives. Utilizing several different types of film makes for days of film processing once I return home.

I really preferred photographing on drier ground where I could walk more freely in the sawgrass savannas and remaining hardwood forests without all the logistical concerns.

Early in the project, I decided to rephotograph scenes that I had photographed as much as 36 years earlier to help depict the progress and speed of the coastal inundation and environmental ruin. These diptychs were difficult to produce for several reasons. For one, my old cameras don’t have G.P.S. to guide me to the exact location of my archival photograph. Most often, I used the trees in the earlier photograph to help position myself for the follow up photograph. Unfortunately, the deforestation caused by rising sea levels had killed many of these locator trees. When I did find the locator trees, it was a gut punch to see my archival photograph next to the now ruined landscape that it depicts. These side by side photographs are very powerful and often provoke a gasp when I do presentations.

Creating a Book

Around eight years ago, I attended two different portfolio reviews with reputable New York City photography gallerists. I was advised straightforwardly that my climate change project should be a book. They both liked the work but said they couldn’t sell the prints because very few collectors want to acquire photographs of environmental ruin. I liked the idea of a book as the medium for this project but I had no idea how to go about publishing a book. After a few dead ends, a friend steered me to the University of Georgia Press in 2020. They were enthusiastic about my Chassahowitzka project.

This was my first book, and it was all new to me. I was assigned an editor and learned how to write a good book proposal. Once the proposal was accepted, I began further research on global warming, sea level rise and saltwater intrusion. Finding four contributing writers who would take instruction was not easy, but I succeeded. They included a marine biologist in Florida who had used my re-photographic diptychs in his studies.

The image selection and image sequence were all my decisions. This really was the most fun and engaging part of the process for me. I had photographs spanning forty-five years spread out everywhere. At the end of the day, I would make a quick video of the arrangement, turn off the lights and walk out. The following morning I would start from scratch again. I got to know all the images very well, who they played well with who and which needed to be alone. Late in this process, I asked the press for two four-page gatefold spreads to help illustrate the impact of the sea level rise. The gatefolds were approved without hesitation.

Once all the image choices were made, I had my negatives drum scanned and settled down to weeks and weeks of file preparation. Working on your image files at 100% in Photoshop on a big monitor is another very good way to learn about your images and how they feel, and how well they work with each other.

The publisher’s book designer was hands off until the end. At that point, we discussed possible book cover images, duotone colors and minor tweaks like image sizes, full-bleed photographs and printing across the gutter. She and I went through the printer’s proofs and discussed sharpening and then, several months later, I had boxes and boxes of my book.

An Unflinching Look: Elegy For Wetlands was published by the University of Georgia Press in 2023, and details of how to purchase the book can be found on his website.

- Stump & Dead Trees, 2015

- Blue Run Shore, 2014

- Dead Tree Hosting Orchid & Air Plant, 2015

- Ruined Forest

- Colonnade, 2012

- Cabin 1987, 2021

- Canoe and Cabin 1988, 2020

- Lower Crawford Creek 1988, 2014

- Creekside 2011, 2021

- Downriver 1986, 2020

- Jerry’s Prairie 2014, 2022

- Kitchen 2004, 2019

- Roof View 2006, 2022

- Upriver 2004, 2021

- Upstream 1987, 2021

- View Downstream 2004, 2022