Destination, Pacific Northwest

Robert Hecht

Robert Hecht has been a dedicated fine art photographer for nearly sixty years. His work has been exhibited internationally and published frequently. Brooks Jensen, the editor and publisher of the photography journal LensWork, in which Robert’s work has been featured numerous times, has described his uniqueness this way: “His is a Zen-like eye…finding the extraordinary in the ordinary.” Robert and his wife, Dale Harrison Miller, live in Portland, Oregon. Robert’s latest book, Stolen Moments: A Photographer’s Personal Journey, can be ordered from MagCloud.com.

It all began one misty morning nearly ten years ago, as I meandered on the still-wet sand of Nehalem Bay on the Oregon coast. It was low tide, and as the shroud of fog began to thin, it revealed a long array of brooding, sculptural forms deposited at the farthest edge of the water line.

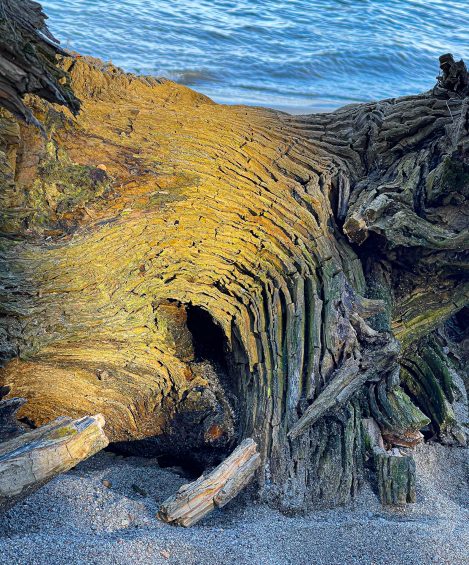

And I did meet them, instantly enthralled with their fantastical forms, and thus beginning a relationship with Pacific Northwest driftwood that continues to this day. It has become an intimate relationship—an obsession if I am honest—and I have revisited many of the largest and seemingly immovable hulks numerous times, getting to know well their individual, swirling designs and textures. Most driftwood comes and goes with the tide changes, but some of these heaviest pieces stay put, lodged into the sand. That is, at least until one of the more dramatic winter storms—of the magnitude that first deposited them on the shore years ago—comes to reclaim them.

Driftwood can be a photographic delight. The dynamic, organic forms of Nature’s sculptures offer endless compositional opportunities; many of them are suggestive of animal or human-like shapes, whether real or of the imagination. The mind’s tendency toward pareidolia can have a field day with these ‘creatures’ of the sea—as one stares at these forms, many of them stare right back!

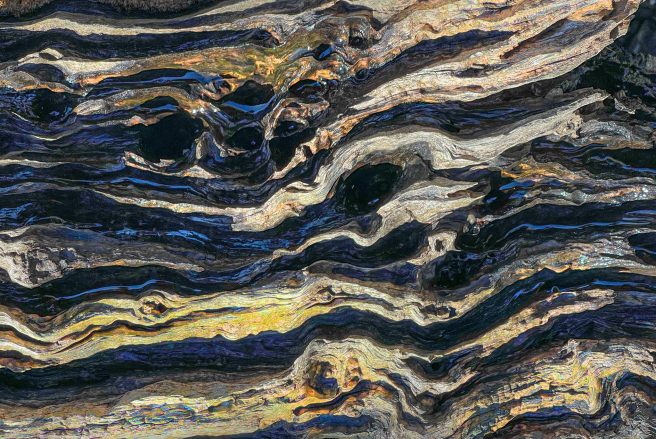

Further, they can offer a multitude of canvases for creating abstractions. Their patterns and textures have been massaged by water, wind and sand, often leaving unique patinas and subtle color changes on their surfaces. I have many times photographed them during a rainfall or just after a rain, when the moisture has dramatically heightened the intensity of the once-latent colors in the wood.

Like all of Nature’s organic materials, they are continually changing, and in that sense, though they have been literally uprooted from their earlier lives, they are still alive and evolving tree forms. Upon a second or third visit, they will inevitably have been transformed further by the elements, perhaps with a slightly changed shape, or a somewhat different texture, perhaps with a scattering of barnacles or a colorful growth of bacteria or algae.

In addition to their visual properties, I have been impressed by another important dimension of the ‘lives’ of these driftwood artefacts—the indisputable reality that they have traveled unknown distances from unknown places to wind up on these Pacific Northwest shorelines. One morning I was moved to compose a haiku about the phenomenon:

misty beach morning—

musing the long voyages

of traveling trees

Yes, they are indeed traveling trees. Where did this huge root cluster originate? What about this thirty-foot long log? Did it come from across the sea or down one of the Pacific Northwest’s many remarkable rivers? And what about this behemoth buried deep in the sand? How long was it afloat before its long-term docking on this beach? What kind of tree was it? When will it move on? Will it ever be replaced by another of its girth and weight?

These are the kinds of questions raised by contemplating driftwood. One thing for sure—you don’t want to be on one of these beaches during a major winter storm when giant waves are tossing these enormous hunks of wood up on the beach like so many matchsticks.

My curiosity about the origins and itineraries of these traveling trees led me to research several scientific articles on the driftwood phenomenon. Some of what I found was not unexpected; however, some of what I learned was indeed very surprising.

Driftwood can come from quite a few different sources, say the scientists. When rivers swell during the spring runoff, it is not uncommon for the high water gradually to undercut the roots of trees growing along the riverbank. Even a mighty Redwood’s tenuous grip on the earth can be jeopardized further each spring, weakened inch by inch or foot by foot until one year when the rushing water and riverbank erosion finally win out and that giant tree crashes into the river.

Depending on the river’s width and depth and the power of its currents, that tree may or may not be swept away on a journey toward the sea. It may first contribute to the formation of a logjam in the river. Such jams can powerfully affect the life of a river and its inhabitants, changing its course, depth, and ecosystem in that area. If that happens, a fallen tree may reside in a logjam for many years or even decades until flood conditions eventually loosen it and send its components downstream.

Smaller trees or logs that have been swept into a river from a logging operation site may be more likely to immediately ride the waves to the ocean. Sometimes the distances trees can travel are as much as several hundred miles.

The journey from a mountain hillside to an Oregon beach may not be a straight shot at all. It may take years, and by the time I happen to encounter a huge relic on the sand at Nehalem Bay, for example, it surely will have undergone many changes. It may have lost all its bark and been smoothed down to resemble a marble sculpture. It may have been broken into many pieces. And it may even have spent a long time buried beneath the sand. Scientists have discovered that driftwood from rivers may reach the ocean and drift in the sea’s currents there for some time, eventually getting washed up on the shore. Because of significant shifts in beach topography, driftwood can, over time, be completely covered with sand and spend years beneath the surface. While buried, the wood can, in essence, be ground smooth by the action of water and sand, as if in a rock polishing device. Eventually, when the beach formations shift again, such driftwood may be tossed once more to pile up at the waterline.

Driftwood may even travel all the way across the Pacific from as far away as Japan, a much greater distance than any river journey. However, much of the driftwood beginning its journey in the East never makes it to the Western United States coast. Scientists say that when driftwood is carried out into the ocean, it can maintain its buoyancy for no longer than a year and a half.

There is much to contemplate when observing a driftwood covered beach along the Pacific coast. A tree that stood its ground for perhaps hundreds of years may then have had an ‘after-life’ of hundreds more, as it traveled by river to the sea and eventually to a wood-strewn beach, where it became subject matter for an enthusiastic photographer such as me. There are so many aspects to appreciate in a driftwood log in addition to its aesthetic properties—an entire, mysterious backstory as a traveling tree.