Eas Urchaidh, Iconic Water

In the highlands of Scotland, near the bleak moorland of Rannoch, the river Orchy begins its journey high in the munros of the Black Mount and winds it way down through Loch Tulla into Glen Orchy. It meanders through this valley overlooked on both sides by hills of dense pine, but itself lined by fine oaks which creak complainingly in the funnelled winds. Several winding miles of gentle gradient precede a chasm in the bedrock, which the river outflanks on all sides before plummeting to the bottom in a series of falls and fingered cascades.

These are Eas Urchaidh, the Falls of Orchy. They aren’t the highest, loudest nor the most spectacular of Scotland’s many waterfalls, but this place has a certain charm. Not a charm of lightness and amiability, mind, but something rather darker; it imparts a slightly unsettling feeling, especially in winter when the surrounding leafless landscape matches its mood. I shall attempt to describe why.

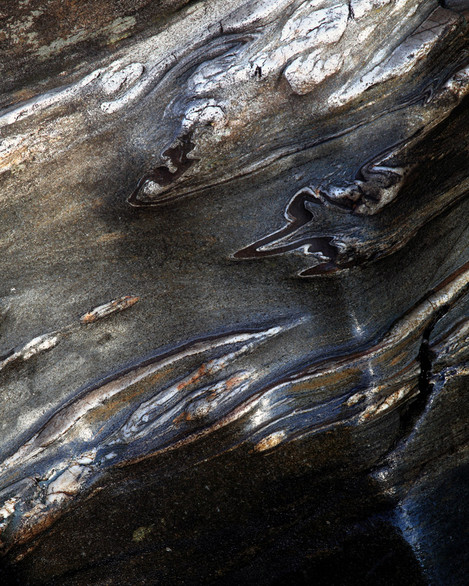

Behind the falling flurries of icy water, the rock of River Orchy is wet and dark and etched with mysterious patterns: curious letters and symbols of gold which resemble runes engraved into the grey-blue rock. If they are runes then they must warn of danger. The broad slab which flanks the chasm and slopes into it is slippery and treacherous, but must be navigated if one is to satiate his curiosity to see it up close. The river is black as ink, reflecting little light as it streams through the chasm’s jagged teeth which clasps it like jaws around prey. The deep channel below is an unrelentingly angry frothy chaos, foam streaming its way under a footbridge and carried around a bend by the swift current. Swirls of froth circle downstream across the widening surface in an ever morphing pattern, some caught in infinitely circling eddies; but surrounding the streams of bubbles the water is murky and dark. Attempts to peer under its surface are mostly futile, despite the undoubtedly lucid water; the depth stares menacingly back. But here and there, hints of forms underneath can just be discerned: what must be the shapes of submerged rocks appear greeny-yellow in the refracted light, their agonised forms twisted and contorted by the water, suggesting something drowned...

I came here last year in late January, following the windy single track road which parallels the river from the old stone Bridge of Orchy, with a curiosity to visit these falls of which I’d seen a few photographs. Intending to spend an hour or two, I found the atmosphere so palpable that I ended up staying the whole day and returning the next to explore and make images. There is something almost gothic and fantastical about this landscape: raw in its geology with its bare stone and branches, and the river bedrock sculpted into fascinating formations hued a subdued palette of grey, blue and ochre. The place utterly caught my imagination. I was alone; no cars passed by on the road and civilisation felt remote. The sky was a drab and featureless shroud which fused with the surrounding hilltops and the only sign of life was the occasional call of a bird some way up the hillside, barely heard above the unerring noise of the river which grated like a detuned television hissing static.

I began to explore the shore further up the river from the falls where I became fascinated by the intricate rocky pavements lining the riverbank. Largely dry and easy to clamber over, they exhibit many varied patterns and textures: in one place a natural swirl of rock, at the centre of which nestled a neat round stone ("Swirl"); in another, an impossibly smooth bowl filled with pebbles, flanked by a quartz stripe ("Stripe").

With not even a hint of directional sunlight there was no shadowing to impart any sense of depth in a photograph, so by framing the formations tightly I could concentrate on capturing their pure forms and subtle colours as abstractly as possible. Images of such landscape fragments focus on the simple beauty of what’s being photographed; they can be most striking when they are made simple. I found myself quickly and methodically sketching interesting forms and sculpted channels using a small compact camera, and after an hour had built up a collection of so many sketched 'candidates' that I quickly realised most of the day would be needed to capture the final versions. Once I neared the chasm, I went back up to where I started and methodically retread my steps from the beginning, reviewing the sketches and revisiting each one by one, capturing the final versions on the main camera as I went.

As I progressed back down towards the falls I eventually found myself at the edge of the large plateau of rock which slopes northwards towards the chasm. Here the river is divided into shallow channels which race each other across the rocky slab. Looking across to the chasm, as a photographer it’s overwhelmingly inviting to hop across to get to its edge and peer into it. From there one would expect to find a great view of the main falls with the chasm and various cascades in the foreground; however, to traverse the plateau I would have to hop or jump on the dry spots between the channels of water running between - and with the channels fringed with ice I would have to be very careful about where I landed. Fifteen kilograms of camera equipment on my back was hardly going to make finding grip easier, and I was completely on my own so one slip would be all it would take for me to fall into the abyss never to be heard from again.

As I progressed back down towards the falls I eventually found myself at the edge of the large plateau of rock which slopes northwards towards the chasm. Here the river is divided into shallow channels which race each other across the rocky slab. Looking across to the chasm, as a photographer it’s overwhelmingly inviting to hop across to get to its edge and peer into it. From there one would expect to find a great view of the main falls with the chasm and various cascades in the foreground; however, to traverse the plateau I would have to hop or jump on the dry spots between the channels of water running between - and with the channels fringed with ice I would have to be very careful about where I landed. Fifteen kilograms of camera equipment on my back was hardly going to make finding grip easier, and I was completely on my own so one slip would be all it would take for me to fall into the abyss never to be heard from again.

Of course I'm not completely foolhardy and without regard to my own danger; I was confident at least in my agility to step safely between the ice and water, and also of the grippy heels of my boots. But what is it about landscape photography that can push self-preservation instincts aside in the pursuit of the image? Some non-photographers might consider landscape photography a fairly sedate pastime, perhaps akin to painting watercolours. But at times it’s the opposite – it can feel like the thrill of a hunt: adrenaline-fuelled, the excitement of developing conditions in the weather and rapidly changing light across the landscape. It's this excitement which drives me to stand in frozen Scottish rivers before dawn, or run full pelt up a fell or across a boggy moor while overloaded with equipment. And even when the effort isn’t so panicked in time, there’s always an extra mile to go on the promise to capture something significant. I’ve camped in subzero temperatures at five thousand metres altitude up in the Himalayas, and driven in deep sand into an African desert in the dark, all in the unquenchable thirst of gaining the trophy. And here was no different: the chasm was beckoning me over, and there was no question of not obeying. So across I hopped.

The reward was the most intricate of rock patterns I found in Glen Orchy. Behind a clean chute of water, falling neatly from a smooth scoop, the black rock was decorated with swirls and seams of quartz. I’m not sure of the minerals, or the geological cause of the patterns, but it’s simply enough for me to capture the wonder of them in an image (“Chute”, “Etched #1”, “Etched #2”).

After carefully retracing my hops back across the slab, I moved a little way downstream from the chasm to where an iron bridge connects the passing road with a forest estate. On the bridge is a plaque dedicated to a young man who died at these falls in recent years; a shrivelled and faded bundle of flowers echoed the sombre mood. Here away from the falls the rocky shore is high and steep, and down below the bridge the water's edge is flanked by highly sculpted rocks. Foam streamed down from the falls in a long ever-evolving line; some broke away only to get caught in concave rocky dead-zones, building into layer upon layer of bubbly scum (“Eddies”). I perched atop the rocks, looking straight down into a sculpted hollow. The foam was being pushed inside with nowhere to go, and the surface now resembled the frothy broth of a witch’s cauldron (“Broth”). Nearby potholes in the rock, perfectly and smoothly oval, could have been pans for mixing unnatural ingredients, I thought. My imagination was starting to react to my feelings about this place and I began to recognise that my images so far were mostly flat and graphical depictions of Orchy’s rocky shore which perhaps didn’t evoke much of its chilling ambience. I resolved to try and find an idea, an angle, that I could use to portray the unsettling nature that pervaded this winter air.

As luck would have it, I very soon found what I was looking for. Under the iron bridge there is a wide shelf above the river, and from there I could just make out hints of watery shapes beneath the surface. I held a polarising filter up to my eye and scanned the river, and with surface reflections removed I discovered a bank of submerged rocks lying in the middle of the riverbed. In the dim green-yellow light the group took on the impression of a creature: an unearthly denizen of the deep, complete with an eye, a toothy mouth and a claw, its expression that of an eternal grimace in the watery cold, like something drowned. I transferred the polariser to the camera and adjusted the angle to block the most photons of light from bouncing off the water’s surface and into the camera; this removed the distractions of reflection and texture from the water which itself become like a black canvas. But I had another problem: the chaotic nature of the foam was changing all the time, and moving rapidly. Firstly I needed it to be in the right position and not obscuring the rock, as it was sometimes drifting over; then, I wanted to capture its intricate patterns, while keeping some sense of its movement. Unfortunately the late afternoon was dimly lit, especially under the shade of the bridge, and the high attenuation of the polariser meant I would need a very fast shutter speed. As the afternoon darkened to dusk, I experimented with the composition and the timing. Once I had settled on the framing, I took many shots with the remote release, trying to capturing the foam in different positions and patterns, but soon after it became clear that it was too dark, the foam was losing its details on the images and tended towards a blurry mess of white streaks. I had to return the next day, and, under similar light, made enough exposures from which one could be selected which best held my vision ("Drowned").

It wasn't that long ago that I was just another photographer enthusiastically running to rugged coastlines to capture radiant seascapes at sunset. Spectacular though such images can be, it can be difficult to elevate them much beyond their literal nature; much like fast food, they may satisfy for a brief time, but quickly fade in the memory. In the last few years the kinds of pictures I like to see and make has changed immeasurably, from gorging on such photographic hamburgers as sunsets and dramatic vistas, to striving to find more contemplative images that better evoke some aspect of myself in the landscape that I find myself in. I think that when an attempt at evoking something beyond what is literally described in an image is successful, then photography truly becomes an artform. In the two days I spent exploring the Falls of Orchy, I’d made a cohesive set of abstract images which were interesting and visually pleasing to me, but I felt didn’t evoke much of the feelings I had of the place. I think this one image manages some success in both.

As I packed my gear into the boot of my rental car to leave Glen Orchy, I still hadn’t encountered a soul. This river is actually a popular destination for white-water rafters and tourists stopping off for summer picnics on their way to Loch Awe. But I found it difficult to imagine, in this shivering place of ice and water and rock in midwinter.

- Swirl

- Stripe

- Broth