A Celebration of Transient Beauty

Tim Parkin

Amateur Photographer who plays with big cameras and film when in between digital photographs.

Paul Kenny

Born in 1951 and educated in Salford, Northwest England, Paul Kenny completed his Fine Art Degree at Newcastle upon Tyne in 1975. In 2004 he returned to North Northumberland where he now lives and works not far from the sea with his wife Margaret.

He has travelled to work in Japan, France and Ireland but the main focus in developing his unique vision were the remote beaches of Wester Ross in north-west Scotland and the Western fringes of the outlying Islands.

Since moving back to Northumberland the windswept beaches between Holy Island and Spittal have woven their way into his work,

In 2000 he was made a Fellow of the Ballinglen Arts Foundation and now, whenever possible, he spends time at their facility in North West Mayo, Eire.

He has work in some of the worlds major public and private collections including Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, the V and A, the National Photography Collection and the National Gallery of Scotland.

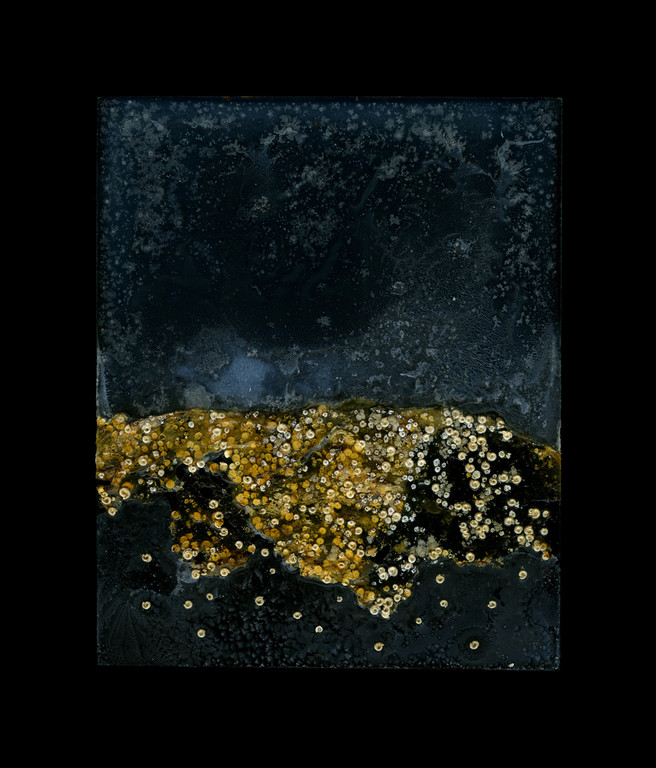

Paul Kenny is an artist who works with the landscape and uses photographic processes to create his work but you'd be hard pushed to know whether to call him a photographer or not. His biggest body of works are constructed still lifes that relate to the sea shore, tidal processes, erosion and time.

Paul has had a joint show, Fragile, at the Chris Beetles gallery over the last month which had a great write up in the London Evening Standard. We didn't get to see the show but we've been wanting to chat with Paul for some time. We started by asking what he's been up to.

Paul I’ve just come back from that London show, Fragile, and there’s nothing much in the diary until next year. I’ll have a bit of time to do some new work. I’m still vaguely toying with the going to Ireland in October. I’m a fellow of the Ballinglen Arts Foundation in County Mayo, Alex Boyd is a fellow as well. I was made a fellow in 2000 and I’ve been out six times so far. It’s just a fabulous place. It’s mainly painters who go; the people who set it up are from Philadelphia and they ran a gallery in New York in the 80s called Dolan Maxwell and they sold up and set the foundation up. I think they’re both of Irish descent so they have four cottages and two shopfronts on the main street behind which hides four studios, an office, a gallery and a print studio. All in a tiny village in West Mayo, when you go, you get a place to live and a place to work and it’s just incredibly relaxed. Most of the people who are made Fellows are American so you kind of get to mix with these diverse group of artists. I work in a very isolated place in an isolated way – I’m not part of any group, I’m not a part of any academic institutions, I’m not day to day linked with these people in my business so its great for me to have the opportunity to enter into some kind of group discourse…..

But also the coastline is just fantastic, it’s west facing Atlantic; There’s nothing between you and the states. It’s on the Gulf Stream so a lot of stuff gets drifted across and I use a lot of that flotsam and jetsam in my work. – Plastic bottles, etc. I found a message in a bottle there which was amazing. It had been put in the sea off Fado island in New Foundland and taken seven years to arrive.

Tim: Did you get in touch with the people who ‘delivered’ it?

Paul I did but they weren’t interested, it was part of a school project. They weren’t that interested but it interested me.

Tim: Do you get the same types of material deposited on your local coastline in Northumberland?

Paul Yeah, yeah. I’m only three miles from the sea so we go two or three times a week. I’ve been going less recently because we’ve got an elderly dog who can’t cope with the pebbles anymore, he just falls over, so we’ve not been going as much. It’s a bit weird going to the beach and leaving the dog at home, it feels very alien. I still go down to gather material, I’ve been using a lot of fisherman’s rope at the moment and bits of net and stuff.

Tim: So what was the basis of the Fragile exhibition?

Paul It was a group show at the Chris Beetles gallery in London in June. I was really proud of my work and I got a fantastic review in the Evening Standard which did no end of good.

Tim: How do you get publicity like that? Is it something the gallery undertakes?

Paul Yes the gallery promote it. I was really glad that Brian Sewell didn’t review it – he hates photography. He was going on recently about the amount of photography in the Royal Academy Summer Show – but this woman called Sue Steward reviewed it who really liked the work and was interested.

Tim: Brian Swell famously dislikes most photographic works. He has a thing about it not having ‘texture’ or ‘surface’

Paul Yes, the hand of the artist. He can’t just see it as a medium and the art is in the way it’s used. He wouldn’t say “I don’t like Charcoal!”

Tim: So for the pieces in the Fragile exhibition – how do you go about creating them? I note you talked about fisherman’s rope in your current work for instance.

Paul Well it comes out of the fact that I’ve almost stopped using a camera. I’ve been doing this for forty years and I slowly, slowly got disillusioned about photography as a medium. It’s a very limited medium when you boil it down and I think you see this when you see people online. People continue to make the same picture over and over again. That’s OK for them if they want to do that but for me it became really boring and easy. You know what a mean? I was mainly making studio pictures of material the beach that I would bring back to the studio and make a kind of still life studio picture around them – and I started to slightly mess with the negative, scratching the negative. I was interested in the plastic bottles I would find on the beach with all of the scratches in them and I thought these scratches were kind of a diary. Some kind of history of the bottle – every single scratch recorded something. And then I thought about each scratch being created by the tide which is created by the moon and the landscape itself is a record of a journey or history. I made a big series called “A Day at the Beach”. You know sometimes in your work you make a huge leap. You do something that you’ve been scared to do for months but you end up doing it and your work takes a big leap.

It’s easy to take pictures of beautiful pebbles or shells or material you collect and I started to think if I’m true to myself about finding beauty in little things then I should use less and less pretty material. So I would walk on the beach and at the end of the walk I would take two handfuls of what was around my feet and put them in a bag and take it home and spread it out to try and make a work out of it. Just to try and prove that I could say the things I wanted to say without using obviously beautiful materials. I mean you look at something like Edward Weston’s nautilus shells, you know, they’re just very, very beautiful objects in themselves.

Tim: They have an intrinsic beauty that is just being recorded

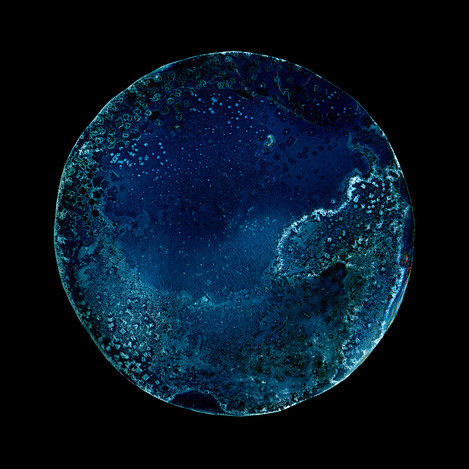

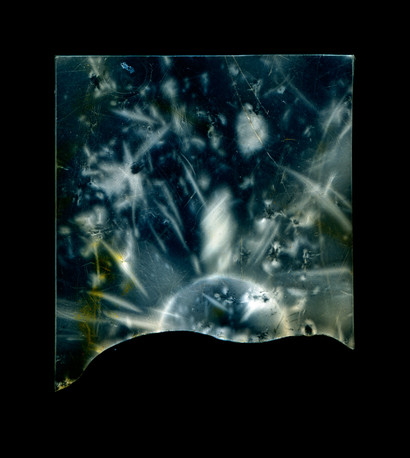

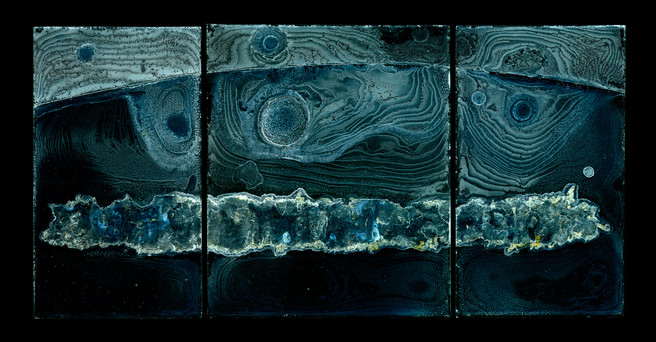

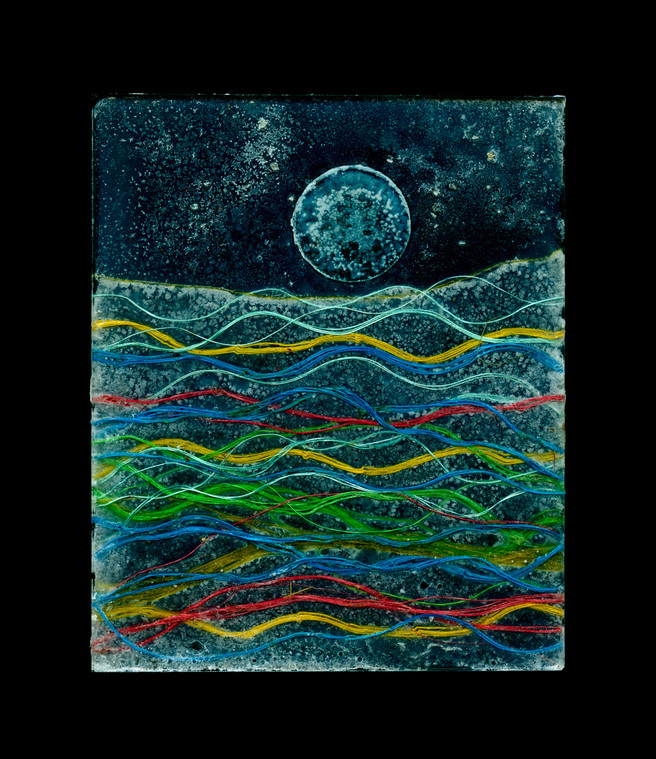

Paul Yeah. And so it came out of that really. And I started to collect seawater and originally I collected the seawater to wet the things I would brought back so that when I would photograph them they would be wet. And then I started to be interested in the seawater itself and thinking, well maybe I can make a picture out of this so I started to dry it on the negatives and I used to put these constructions into an enlarger and print through them to make a black and white print. And slowly, slowly, slowly over a period of ten years now these plates I was making – I used 5x4 inch pieces of glass and I kind of construct these things with seaweed or seawater and then I’d put them in an enlarger and print from them.

But slowly the plates were becoming more beautiful in of themselves and more interesting. So now I decided that I am the camera and I create a negative and now I scan them instead of printing from them.

Tim: So are these scanned or photographed then?

Paul They’re scanned now. But that is a photograph – I’ve come up with a definition that works for me – “A photograph is a repeatable image made using light”. And that works for me.

Tim: And scanners are cameras at the end of the day as well

Paul So they’re basically 5x4 sheets of glass with stuff from the landscape itself adhered to them .

Tim: So is the piece of artwork the photograph or the object?

Paul yes for me it’s the photograph that is the piece of art. A lot of people have said to me that I should actually exhibit the glass plates but the images are drawn first as part of the design and the finished piece for me is the photograph and then I have to construct something to get me to that point.

Tim: So once these are scanned do you do any post processing work to clean them up or adjust the colours/hues in any way?

Paul I don’t tend to do much of that. There’s lots of fluff and grit in the seawater but I tend the leave them in. Sometimes I scan with the lid of the scanner open, sometimes as a negative but mostly I scan with the plate on the scanner bed and the scanner open. And I sometimes light the back of the plate as well so there is light going through the plate and reflected from it.In the computer I do saturate the colour slightly but all of the colours in the seawater, when they scanned, come out those turquoisey blue colours.

Tim: So is this in a way like Andy Goldsworthy’s work being a combination of a real thing and it’s photograph. Where the photograph is often the final work.

Paul I’m a big, big fan of Andy Goldsworthy, in fact he’s a buyer of my work.

Tim: It’s interesting that he plays down his photography as a part of his artwork.

Paul He does indeed. I was invited to spend a day with him once at his studio in Dumfries and we went out and he was working on a piece and he just had his rucksack with a few cameras at the bottom and once he’d done his piece of work he pulled out this camera and he had no lens cap and it was dust on the lens and he makes these photographs. I said to him do you not take more care about them. And he says “no not really – it’s just what I do”

Tim: Is he quite a considered photographer when it comes to creating the picture?

Paul He does but he wasn’t particularly involved with the process. He just pulled out his tripod and – he was using at the time a Fuji 6x17 camera and he just photographed what he made. He obviously knows what he’s after. Just the other day I watched a documentary on You Tube about his work and he was making this piece with ice and he made it so he knew the sun was setting in a certain point and that was part of the picture.

Tim: How do you think your work is developing at the moment?

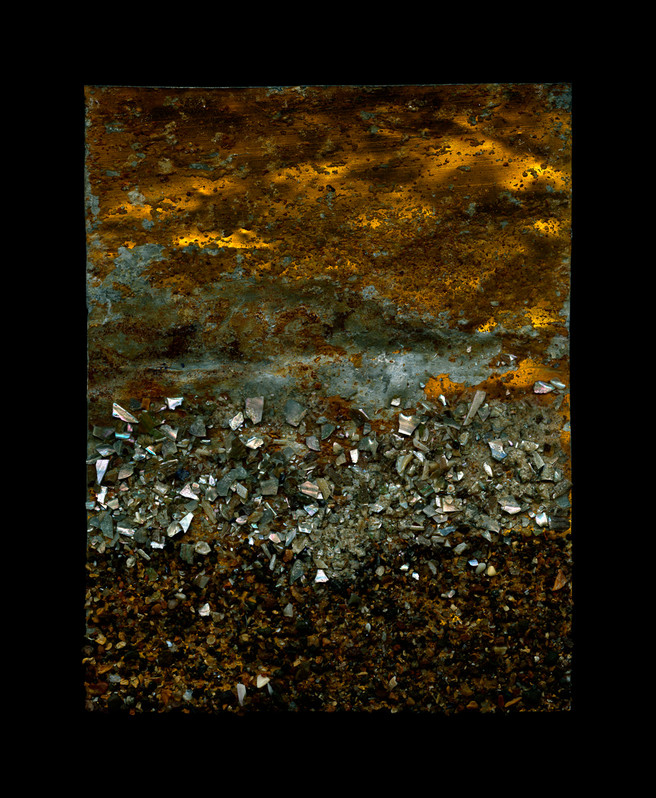

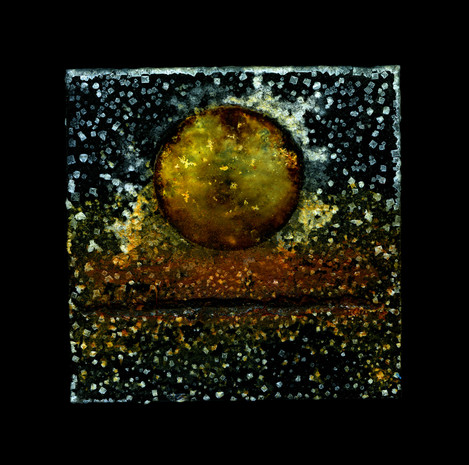

Paul At the moment my work is going very minimal. I’m kind of paring it down. I’m interested in rust at the moment. I find little pieces of metal. One of my favourite things to find on the beach is can bottoms. Because the bottom is a concave, rigid structure the bottom stays more intact so you quite often find them on their own. If I put those on the glass plate you get a lot of rust – particularly if they are made of iron. So some of the pictures in the show had this rust element. And if I keep dripping seawater on over maybe a month the can rusts and rusts and rusts and leaves a rusty stain on the glass which is very beautiful. I’ve become more interested in the emulsion, the idea that I’m creating a type of emulsion on a piece of glass which is very similar to an old glass plate photograph. Just shadows on the glass really. With the nylon rope, I liked the way it unravelled and naturally fell into the shapes of waves.

Tim: You took a bit of diversion when you were producing the O Hanami project…

Paul That was a very specific project. I took a year out two years ago because of this problem, a problem that has spanned my whole career in that I cannot continue to make the same picture. Once I become stale and I’m making the same picture over and over I get very, very disillusioned and it’s caused me huge problems. I’ve been with five different galleries in London and we all get to this point where I’m making these pictures that they love and they can sell and I don’t like changing or restricting the flow of my work and we part company.

Tim: It’s a common problem with artists and galleries I think.

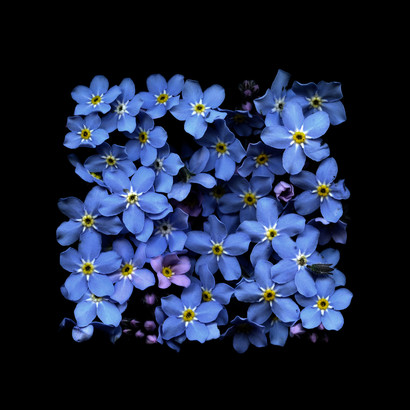

Paul It is! So I was just jaded. I did a big commission on the Isle of Mull and produced a show for the An Tobar gallery called “Mull Works” which was all sea works and at the end of it I was really happy with the work and really content with where I was. But I started working again after the commission and I was rehashing the same picture. Something happened by chance to force me to use my eye and my techniques to make work about a different landscape…. this was the time we got snowed in a couple of years ago. Where I live is very prone to snow and it was the winter of 2010 and we got snowed in for four weeks – we couldn’t get a car out at all – couldn’t get to a shop. My studio is at the side of the house. It’s very small, a little old barn, and I need to go out the back door and round the corner to get to it. And I couldn’t get round – I was digging my way to the studio and I dug up this old little Hosta leaf from under the snow and I took it into the studio and I just started to flatten it out a look at it and I stuck it to a piece of glass the way I would do with seaweed and it looked really beautiful so I started to try to make these pictures out of just scraps of garden material as the snow melted. I thought, this is interesting – I might just stop doing this sea stuff and just do this project for a year. It was linked in with other things as well. I went to Japan quite a few years ago but I did actually witness this ceremony called O Hanami when the cherry blossom is out and they go into the park and sit under the cherry trees and when the wind blows and they get covered in petals they all applaud and drink. The literal translation of the phrase is “A Celebration of Transient Beauty”.

Tim: What a beautiful concept

Paul Yes! I loved it – I just thought the concept of this celebrating this beautiful little pink petal that’s alive and beautiful for about a day was wonderful. So that was a part of it and I thought I could do this for a whole year because we have things that come out and are very beautiful for a short period in this country so why should it be just Japan. A complete show evolved in my head this whole exhibition that started off with these dead Hosta leaves and went right through the summer through brilliant tulips and explosions of colour and through to winter where it went back to dried leaves. The whole show would start in browns and went through to colours and then back to browns.

Tim: Was it finally hung in the gallery like that?

Paul Yes, yes. The show was just as I imagined it, Chris Beetles did a fantastic job and produced a lovely catalogue, the show was really successful and got me a lot of attention but when it was over it was good to get back to the shoreline.

Tim: Did that journey away refresh your work?

Paul It did indeed. I went back with a fresh eye and different ideas and I thought this work I mde for the Fragile show was really good work and different to what I’d done before and I’ve learned some new things. I don’t know if the gallery liked it because for them it was me jumping about a bit again. They like you to be consistent.

I don’t know how people live with themselves creating the same work all of the time. It’s the same with photographers as well. Some of these people who really promote themselves and are considered quite highly thought of but they revisit the same idea many, many times.

Tim: Going back to photography – how do you think it can be creative?

Paul I don’t know really. I think a lot about these kind of issues. It’s interesting that on the whole galleries don’t like inkjet prints at all. Since I discovered Jack Lowe in Newcastle and once I saw his work and what he can do it completely changed my mind about what a digital print was. I used to pride myself on the fact that my silver gelatin prints were beautiful objects. If you saw one and held one you’d think it was a beautiful thing. And I’d never seen a digital print that had that same feeling until I saw what Jack does and I thought “My god! These things are gems!” and I’ve been working with him for five years and we’ve worked really closely and we’re producing something that I think is unique. It’s a new beauty that wasn’t possible before. So there is still room for creativity in the photographic process.

Tim: What types of photography do you enjoy?

Paul Well I went to see that Landmarks exhibition at Somerset House. The two people I like I suppose are Susan Derges who I love and she uses photography in a creative way and Garry Fabian Miller (ed: See the Camera-less Photography exhibition that ran at the V&A) .

I did see a bit at that exhibition that was really interesting but the prints weren’t made for the environment. A lot of them were far too big. The Susan Derges was covering a whole wall in a room that you could hardly move away from. The Nadav Kander and Simon Norfolk were too large as well.

Tim: We’ve got the Becher’s to thank for that I think – If you can’t make something original, make it bigger

Paul That’s right – that’s what I thought. In all the reviews I saw of the show nobody picked that up. I got really interested in David Maisel’s work which is quite similar to mine in it’s ideas but done from as far away from the earth as you can get. Very poor quality printing. I try and make my prints into these beautiful things that make you salivate when you get near them.

Chris McCaw was very good with the sunburn pictures and I did like some of the scientific images from other sources like NASA and Hubble.

I was massively influenced a while ago by that full moon exhibition at the Haywood by Michael Light. He had access to like 30,000 negatives that were taken on the moon. That was very impressive at the time and a lot my pictures from At the Beach were recreations of pictures like that but using stuff from the earth. I kept on thinking “Why are these pictures so powerful – they’re just pictures of the floor!?”. I should be able to make an equally powerful image with the earth’s floor. I used a lot of raking light across the surface like the moon pictures. There is still an element of that in my work I think.

Tim: Do you always have an intended scale of your final work?

Paul That’s quite an interesting question. I don’t know. That’s one of the things I’ve found liberating about digital image making. I hadn’t worked in colour ever before I started working digitally and I felt liberated but also by the scale. I like printing big because I can do it but it has to be linked in with where this pictures going to be. I don’t like the idea of doing things huge for the sake of it. I tend to work at about 20x24 – a sort of domestic scale.

Tim: How does a typical day at the beach go for you?

Paul Well it’s just a collecting thing these days and a thinking space for me. I don’t ever take a camera – actually I do, I take a Lumix digital as a notebook and I do like playing around with instagram and snapseed as a sort of playful thing. But mainly it’s in the studio. I always have six or seven things on the go at once. Because the stuff takes so much time to dry things you can’t get onto the next stage quickly. Particularly at the moment with the rust work, I’m having to induce things to rust. It’s a process that you can’t hurry – it just happens. So lots on the go at once. I do some drawings as well. I’ve just found a fantastic bit of fertiliser bag on the beach and it’s so creased and battered by the sea that when I scan it it looks like marble because the creases are white and the bag has a bluey tone to it. So I’m cutting up squares of that and working out how I can match it up with some of the other things I’m doing. It tends to be very hands on in the studio – the landscape itself is the inspiration really.

Tim: What do you do when you aren’t working on art.

Paul Nothing! That’s what I do!

Tim: Do you have any other hobbies or listen to music?

Paul Yeah, we’ve got a big garden so we grow a lot of vegetables. Yes I listen to music too, it’s very important for me. I listen to music all of the time when I’m working.

Tim: What sort of music?

Paul A huge variety. I tend to like things that are quite long winded, I’m listening to Philip Glass at the moment, sort of tinkling away in the background. I try and keep up with it though so I’m always trying to find new music. I listen to a lot of John Hopkins at the moment.

Tim: Back to your work again – What happens to the ‘originals’, the ‘negatives’ as it were? Do you recycle them?

Paul Yes they tend to get recycled or thrown away. I keep the occasional ones, they’re very good to take to talks. Some people just can’t get there head around what I do and when I get a plate out with the dried rust and water and string on it it suddenly becomes clear.

Do you know Michael Jackson? I’ve been following his blog quite recently and I’ve emailed him saying he’s being too honest. I don’t think he should be telling people how he did those pictures in the fishtank. I think it somehow detracts from them. They were beautiful and mysterious and now they’re not. It’s something I’ve toyed a lot with, whether I should tell people how I do what I do. I like the idea that people should work it out. I have a friend who has one of my pictures and she keeps it by the telephone and she still phones me up after ten years telling me she’s just found another bit you know or “how did you do this?”. I like the idea that people can do that.

One of the issues with photography at the moment is that there is just too much of it. We’re bombarded by photographic images. You wouldn’t listen to a symphony once and say you understand it. You’d listen to it over and over again until it becomes a part of you and I like the idea that people could look at my work in that kind of way over a long period.

Tim: People do seem to like to show too many pictures. They aren’t particularly great self-editors.

Paul The other thing I find with photographers is that they tend to only look at photography. I think like you, you’ve obviously seen Andy Goldsworthy and know his work but that could inform a landscape photographers work far more than looking at Flickr.

These new pictures that were in the Fragile exhibition were heavily influenced by The Boyle Family. They have this thing where they would go around with a wood worker’s set square and throw it in the air and where it would land would be the bottom left hand corner of their piece and they would recreate that square of the world and then hang it on a wall. They’re wonderful – they blew me away. I saw a couple of them at the Tate in Liverpool, the sand ripples and I thought that’s fantastic. So a lot of newer pictures in the Fragile show have got sand in them.

Tim: Which other artist do you find inspire you

Paul Ooh – Rothko, let’s start with the big ones, erm. One of the artists who influenced me heavily early on was a Yorkshire artist called David Blackburn – he lives in Huddersfield. I was blown away by his work a long, long time ago. About 30 years ago – he does pastel drawings of the moorlands, he calls them visionary landscapes. I was influenced by the fact he was just an ordinary bloke. He owned two terraced houses in Huddersfield – one he lived in and one he worked in – he just toddled between the two, never married, he just worked. He does these panels of about twenty pieces joined together making these huge pieces and when I was at the end of my black and white printing phase I was making these pieces that had 5 or 6 or 8 pictures joined together to try to make a bigger piece out of smaller pieces. In 2007 I had a kind of crisis – I was sponsored by Forte in Hungary, for seven years I didn’t buy a piece of paper, they were fantastic. I got this email one day – we’re closing the factory tomorrow and that’s it. Slowly other bits of changed or stopped being made. They stopped PanF in 5x4 sheets. I came to this point where it was all falling apart and then I was introduced to Jack. I didn’t exhibit for a couple of years while we worked on a digital way of making work.

I’m actually thinking of using film again though, black and white but then had tinting. I’ve been working on some hand tinting of inkjet prints.

Tim: We look forward to seeing that in the future - thank you very much for your time

Paul: It was a pleasure.

You can see more of Paul Kenny's work at his own website www.paul-kenny.co.uk or at the Chris Beetle's gallery website www.chrisbeetlesfinephotographs.com