Naturalistic photography as art (and science)

Keith Beven

Keith Beven is Emeritus Professor of Hydrology at Lancaster University where he has worked for over 30 years. He has published many academic papers and books on the study and computer modelling of hydrological processes. Since the 1990s he has used mostly 120 film cameras, from 6x6 to 6x17, and more recently Fuji X cameras when travelling light. He has recently produced a second book of images of water called “Panta Rhei – Everything Flows” in support of the charity WaterAid that can be ordered from his website.

Pure imitation of nature (even if it were possible) won’t do, the artist must add his intellect, hence his work is an interpretation. …. Never rest satisfied then until these requirements are all fulfilled, and destroy all works in which they are not to be found ~Peter Henry Emerson, 1889

In 1889 Peter Henry Emerson (1856-1936) published a book called Naturalistic Photography for Students of the Art1. Emerson is now well-known as one of the foremost 19th Century photographers, particularly in his pictures of rural Norfolk and Suffolk2, many of which show people working in the landscape.

The book is in part a technical handbook and glossary, in part a short history of naturalism in art, in part a guide to composition, but mostly a polemic for how to justify photography being considered as an art. It is also great fun to read, both because Emerson cannot resist expressing some pretty strong opinions (with some good quotable quips), but also for the way in which some of his comments relate to modern day mores in photography.

Although born and spending his early life on his American father’s sugar plantation in Cuba, Emerson was educated in England, finishing with a medical degree from Clare College, Cambridge in 1885. It seems that he first bought a camera to pursue his interests in ornithology, but only a short while later he was a founder member of the Camera Club of London, and in 1886 was elected as a Council Member of the Photographic Society (the forerunner of the RPS).

Around this time, he gave up working as a surgeon to become a photographer and writer. His images are often illustrated in histories of photography (especially Gathering Water Lilies, Gunner Working up to Fowl, Setting the Bownet). The illustrations here have been chosen to represent some of his less well-known, more landscape oriented, images from a number of his books5. His last book, often considered his finest, Marsh Leaves, was published in 1895. He was then only 39 but lived for another 41 years, and the whole of his published photographic work was produced in only a decade.

Emerson’s work is often grouped with the broad movement of Pictorialism in photography. This term was first introduced in the title of the book Pictorial Effect in Photography 6 by Henry Peach Robinson, published in 1869. Pictorialism had a period of popularity in both Europe and America at the end of the 19th Century up until the 1920s and included photographers such as Robinson himself, Oscar Rejlander, Alvin Langdon Coburn, Edward Steichen, Gertrude Käsebier, Annie Brigman, Sarah Sears, Clarence H. White, Alfred Stieglitz and even some of early Ansel Adams work. Pictorialism was also popularised by the Linked Ring group in England, the Photo-Club de Paris in France and the Photo-succession in America. Common themes in Pictorialism were the aims of conveying atmosphere and mystery (often by the use of soft focus) and demonstrating evidence that the image had been made by the artist. Underlying the movement was the perceived need for photography to be considered as an Art, rather than as simple mechanical reproduction as it was often represented by artists in other media.

Emerson’s early photographs were in sharp focus, but he felt that this did not properly reflect what was seen by the eye. He experimented for a while with soft focus but again found it difficult to properly express a naturalistic style. In Naturalistic Photography, he argues on the basis of the science of vision that the eye sees only a limited depth of field in sharp focus at any one time and that therefore photography should reflect this to be more realistic and artistic. He did not, of course, use the word bokeh (which was only borrowed from the Japanese in this context more than a century later in 1996/7), but does refer to depth of focus in expressing what the eye, and camera lens should see.

In this, he was somewhat in conflict with the prevailing Pictorialist ideas of the time that art photography should show the effect of the hand of the artist. This was done in three main ways: by making prints that made use of multiple negatives (still mostly glass plates at this time); by the use of colour tints in printing; and thirdly by retouching negatives by hand, including the use of drawing and brush strokes. Emerson argued strongly against all these methods: “Retouching is the process by which a good, bad, or indifferent photograph is converted into a bad drawing or painting”, and he only ever published photos based on a single, unretouched negative. It has been suggested that when he found that he could not really change these prevailing views, he stopped publishing his photographs and concentrated on writing. But this time period also coincides with the introduction of film and more portable and affordable cameras by the Eastman Dry Plate and Film Company (which became Eastman Kodak in 1892). It is certain that Emerson would not have expected the standards of photography to be raised as a result. Perhaps he despaired of the more widespread use of photography by the uneducated (see below) already in 1895!

Naturalistic Photography consists of three “books”, each containing several chapters. Book I is on Terminology and Argument; Book II on Technique and Practice (including a history of naturalism in art); and Book III on Pictorial Art. There is also an appendix on Photographic Libraries and Books7. In the 2nd Edition a written version of a lecture given by Emerson at the Camera Club in 1889, entitled Science and Art is included as an additional appendix. The text is unexpectedly preceded by many pages of adverts (for companies making different types of prints – argentic-bromide, argentic-gelatino-bromide, platinotype - and enlargements, for chemicals and photographic supplies, and for Ross and Dallmeyer lenses.

The book opens with a citation:

Beauty is truth, truth beauty, —that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know. ~ Ode to a Grecian Urn by Keats

and Emerson writes: “We propose in this book to treat photography from the artistic standpoint. We shall give enough science to lead to a comprehension of the principles which we adduce for our arguments for naturalistic photography, and we shall give such little instruction in art as is possible by written matter, for art we hold is to be learned by practice alone.” He stresses this opinion strongly several times; that you need to be a trained artist to appreciate the aims and scope of photography as art. He himself, of course, had trained as a doctor, but from the text was evidently well read in the history of art (it seems he also pursued interests in billiards, rowing and meteorology!).

He also defines art as follows: “Art is the application of knowledge for certain ends. But art is raised to Fine Art when man so applies this knowledge that he affects the emotions through the senses, and so produces æsthetic pleasure in us; and the man so raising an art into a fine art is an artist. Therefore, the real test as to whether the result of any method of expression is a fine art or not, depends upon how much of the intellectual element is required in its production …. For this reason, everyone who writes verse and prose, who sculpts, paints, photographs, etches, engraves, is not necessarily an artist at all, for he does not necessarily have the intellect, or use it in practising his art.” Evidently, he was of the opinion that he passed such a test, but one can imagine how well these opinions went down with some of his fellow photographers. He does seem to have been rather combative by nature.

He also does not seem to have thought much of the work of many photographers. Indeed, he explicitly states that: “Of the thousands who have practised photography since 1839, and who are now dead, how many names stand out as having done work of any artistic value? Only three. One a master, who was at the same time a sculptor, namely, Adam Salomon; one a trained painter, but without first-rate artistic ability, [Oscar] Rejlander; and one, an amateur, —Mrs. [Julia Margaret] Cameron.” In respect of the latter he comments: “Among the few satisfactory portraits we have seen are, as we have already said, those by the late Mrs Cameron. In all of these, that fatal sharpness has been avoided; her focussing was carefully attended to.”

By this, he is not advocating soft focus as a means of making photographs as art. Indeed, he writes: “Some writers who have never taken the trouble to understand even these points, have held that we admitted fuzziness in photography. Such persons are labouring under a great misconception; we have nothing whatever to do with any “fuzzy school.” Fuzziness, to us, means destruction of structure. We do advocate broad suggestions of organic structure, which is a very different thing from destruction, although, there may at times be occasions in which patches of “fuzziness” will help the picture, yet these are rare indeed, and it would be very difficult for anyone to show us many such patches in our published plates. ”

But he equally argues against using extreme depth of field which he suggests should be reserved for the realms of scientific and industrial photography. He allows that these are perfectly good uses of photography in their own right but they cannot be considered art. “Much time and expense would have been saved had the pioneers of photography had good art educations as well as the elementary knowledge of optics and chemistry which many of them possessed, for without art training the practice of photography came to be looked upon purely as a science, and the ideal work of the photographer was to produce an unnatural, inartistic and often unscientific, picture. It is, indeed, a satire on photography, and a blot which can never be entirely removed, that at the very time the so-called scientific photographers were worrying opticians to death, and vying with each other in producing the greatest untruths, they were all the while shouting in the market-place that their object was to produce truthful works …… this “sharp” ideal is the childish view taken of nature by the uneducated in art matters, and they call their productions true, whereas, they are just about as artistically false as can be.”

So, to make the grade as art, Emerson suggests that photographs should not be too fuzzy and they should not be too sharp. They should, indeed, reflect the way the eye sees, focusing on a single plane at any one time. “As we said before, therefore, the principal object in the picture must be fairly sharp, just as sharp as the eye sees it, and no sharper; but everything else, and all other planes of the picture, must be subdued, so that the resulting print shall give an impression to the eye as nearly identical as possible to the impression given by the natural scene.”

He goes further to suggest that the choice of lenses should also reflect the angle of view of the eye: “This proportion should be as two to one, that is, the focal length of the lens should be as a rough working rule twice as long as the base of the picture. We arrived at the result by making a series of drawings on the ground glass of the camera, and comparing them with a perspective drawing made upon a glass plate. Opticians have arrived at the same conclusion, for we find this is the rough rule stated by Mr. Dallmeyer in his “Choice Lenses”.” Furthermore: “If it be a commonplace photograph taken with a wide-angle lens, say, of a stretch of scenery of equal value, as are most photographic landscapes, of course the eye will have nothing to settle thoughtfully upon, and will wander about, and finally go away dissatisfied. But such a photograph is no work of art, and not worthy of discussion here. Hence it is obvious that panoramic effects are not suitable for art, and the angle of view included in a picture should never be large.” (Now he has upset me too – I have a goodly collection of 617 panoramas8!)

In terms of exposure, he recommends that these should be quick: “We have advocated quick exposures as absolutely essential to artistic work, and it follows, therefore, that in making quick exposures there is less liability of going wrong; so, the two, work hand in hand. He who exposes slowly misses the very essence of nature, and it is this very power of exposing so quickly that gives us a great advantage over all other arts…. if we see and desire to perpetuate an effect, it is ours in the twinkling of an eye, and thus in a really first-rate photography there will always be a freshness and naturalism never attainable in any other art.” But, on the other hand, not too quick: “And here we would state definitely that the impression of these quick exposures should be as seen by the eye, for nothing is more inartistic than some positions of a galloping horse, such as are never seen by the eye but yet exist in reality, and have been recorded by Mr. Muybridge.”

These recommendations are effectively a summary of using the science of vision to produce photographs that can attain the level of being considered as art. This is what Emerson considers as Naturalism (he notes that the term Impressionism has also been used: “although we think the work of many of the so-called modern “impressionists” [the painters] but a passing craze”). In his glossary Naturalism is defined as: “the true and natural expression of an impression of nature by an art. Now it will immediately be said that all men see nature differently. Granted. But the artist sees deeper, penetrates more into the beauty and mystery of nature than the commonplace man. The beauty is there in nature. It has been thus from the beginning, so the artist’s work is no idealising of nature; but through quicker sympathies and training the good artist sees the deeper and more fundamental beauties, and he seizes upon them, “tears them out,” as Durer says, and renders them on his canvas, or on his photographic plate, or on his written page.”

He thinks that:” Naturalism has been the watchword of all the best artists, and that, after all, there are but few artists in any age. Many painters and modellers and sculptors there be, but artists are few indeed”, and that: “It is, then, the absolute duty of every picture-buyer, who has any regard for truth, and any interest in the future of art, to learn to study nature carefully, and to buy only that which is true and sincere, and let the pink and white school of dishonesty die of inanition”.

He is also critical of other “art” of the time: “At the present day there is a craze for anything Japanese, but like all crazes it will end in bringing ridicule upon Japanese work; for their work, though fine for an uncivilised nation, is absurd in many points, and this stupid craze by indiscriminate praise will only kill the qualities to be really admired”, while: “Turning to Switzerland, we find no name worth mentioning; and here we would ask those who trace the effects of sublime mountain scenery on the character of men, why there has been no Swiss art worth mentioning? Of course, the explanation is simple—because art has nothing whatever to do with sublime scenery. The best art has always been done with the simplest material.”

Great Yarmouth Harbour, from Wild Life on a Tidal River. The Adventures of a House-boat and her Crew, 1890

One of the essential elements of Emerson’s Naturalism is the choice from Nature and he has some interesting thoughts on composition.

In Book III, Chapter III Out-door and In-door Work, there is a section on Landscape. Emerson’s advice is, as usual, rather extreme: “The student who would become a landscape photographer must go to the country and live there for long periods; for in no other way can he get any insight into the mystery of nature. All nature near towns is tinged with artificiality, it may not be very patent but the close observer detects it.”

A misty morning at Norwich, from On English Lagoons: being an account of the voyage of 2 amateur wherrymen on the Norfolk and Suffolk rivers and Broads, 1893

He is also very much against the idea of what we would now call photographic workshops: “Here let him be cautioned against taking part in any of those “outings,” organised by well-meaning but mistaken people. It is laughable indeed to read of the doings of these gatherings; of their appointment of a leader (often blind); of the driving in breaks, always a strong feature of these meetings; of the eatings, an even stronger feature; and finally of the bag, 32 Ilford’s, 42 Wrattens', 52 Paget’s, &c.” and against photographers going to well-known locations: “Again let the student avoid imitation. If he knows that an artist has been successful in one place, do not let him, like a feeble imitator, be led thither also, for the chances are, if his predecessor were a strong man, that he will produce commonplaces where the other produced masterpieces, and thereby confess his inferiority. It is far better to be original in a smaller way than another, than to be even a first-rate imitator of another, however great.”

Chapter IV in Book III contains some Hints on Art, many of which are worth quoting. To cite just a few, if only for their resonance with issues being discussed today (and by later commentators on photography).

Remember that the original state of the minds of uneducated men is vulgar, you now know why vulgar and commonplace works please the majority.

Be true to yourself and individuality will show itself in your work.

Do not be caught by the sensational in nature, as a coarse red-faced sunset, a garrulous waterfall, or a fifteen-thousand-foot mountain. Prettiness. Avoid prettiness—the word looks much like pettiness, and there is but little difference between them.

The value of a picture is not proportionate to the trouble and expense it costs to obtain it, but to the poetry that it contains.

It is not the apparatus that does the work, but the man who wields it.

When a critic has nothing to tell you save that your pictures are not sharp, be certain he is not very sharp and knows nothing at all about it.

Art is not to be found by touring to Egypt, China, or Peru; if you cannot find it at your own door, you will never find it.

So we can conclude that, according to Emerson, if you really want your work in photography to be considered as Fine Art, you really need to be trained as an artist, you need to be careful about your depth of field and angle of view being as the eye would see it (no focus stacking, no telephoto or wide angle lenses then); you need to live in a landscape for weeks or months to appreciate it fully; you should avoid all rules of composition, all workshops, well-known locations, and retouching (our post-processing). He also suggests that the artist should not take too many pictures: “the student of photography who wishes to produce artistic work must not hurry or over-produce. One picture produced in a month would be well worth the time and trouble spent on it.” Things have evidently changed in photography in the last 130 years, though there is, of course, a modern slow photography movement, some of whom still use essentially the same large format equipment – even if the idea of using camera movements now is to make the images far too sharp!). But to leave the last word with Emerson.

Here, then, we must leave photography at the head of the methods for interpreting nature in monochrome, and we feel sure that anyone who comes to the study of photography with a rational and an unbiassed mind will admit there is no case to be made out against it as a means of artistic expression…..It must not be forgotten that water-colour drawing and etching have both been despised in their time by artists, dealers, and the public, but they have lived to conquer for themselves places of honour. The promising young goddess, photography, is but fifty years old. What prophet will venture to cast her horoscope for the year 2000? ~ Book III, L’Envoi: Photography - A Pictorial Art

Except that in 1891, just one year after the 2nd edition of Naturalistic Photography, during a brief spell in London away from his barge on the Norfolk Broads, Emerson published a short, black bordered, treatise that was titled The Death of Naturalistic Photography10. In this he changed his opinion that photography could be considered an art form. There have been a variety of interpretations of this change, but it seems that the major factors were experimental evidence by Ferdinand Hurter and Vero Charles Driffield that there was a fixed relationship between exposure and density of a negative, changing Emerson’s belief about the value of controlled development to achieve artistic effects on tone; and also his readings in evolutionary psychology and human perception, particularly the books of Herbert Spencer. He also cites an exhibition of the work of Hokusai prints (in London in 1890), and “conversations with a great artist after the Paris Exhibition.” In fact, although his last books of photographs were published well after this, none of the images included appears to have been taken after 1891 and the appearance of The Death of Naturalistic Photography.

References

- 1P H Emerson, 1890, Naturalistic Photography for Students of the Art, 2nd Edition, E&F Spon, New York

- 2His first book, published in 1885, was called Life and Landscape on the Norfolk Broads and included 40 platinum prints. Many of his other books and prints were focused on East Anglia subjects. He spent a lot of time there, although based in Chiswick in London at the time Naturalistic Photography was written and published.

- 3Portrait from Wikipedia at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peter_Henry_Emerson

- 4Digital images courtesy of the Getty Museum open content program.

- 5A greater selection of his work may be found at the Getty Museum site at http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/artists/1726/peter-henry-emerson-british-born-cuba-1856-1936/

- 6Henry Peach Robinson, 1969, Pictorial Effect in Photography: Being Hints on Composition and Chiaroscuro for Photographers,

- 7In this Appendix Emerson lists (amongst other books on optics, chemistry, and photo-mechanical reproduction) the Treatise on Photography by Captain Abney (Longman); and the Science and Practice of Photography by Mr. Chapman Jones (Iliffe and Son). There was already a History of Photography by Mr Jerome Harrison (Trübner and Son); and a Traité Encyclopédique de Photographie, par Dr. Charles Fabre. (Gauthier-Villars, Paris).

- 8Some of which can be seen in On Landscape Issue 162 at https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2018/06/reflective-photography-essence-place/

- 9J. Burnet, FRS, 1880, A Treatise on Painting in Four Parts, H. Sotheran & Co. London

- 10There is an interesting article by Carl Fuldner about the evolution of Ermerson’s ideas in the Tate Museum papers at https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/27/emersons-evolution

- On The River Bure, from Life and Landscape on the Norfolk Broads, 1886

- The cover of Marsh Leaves, published in 1895

- The Snow Garden, from Marsh Leaves, 1895

- Rime Crystals, from Marsh Leaves, 1895

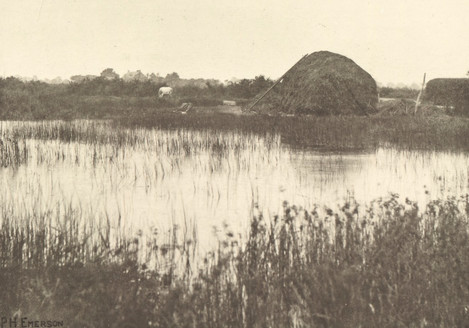

- Autumn Floods, from Life in Field and Fen, 1887

- Leafless in March, from Pictures of East Anglian Life, 1887

- Broxbourne Church, an illustration from an edition of Izaac Walton’s The Compleat Angler, 1888

- Great Yarmouth Harbour, from Wild Life on a Tidal River. The Adventures of a House-boat and her Crew, 1890

- A misty morning at Norwich, from On English Lagoons: being an account of the voyage of 2 amateur wherrymen on the Norfolk and Suffolk rivers and Broads, 1893

- The Misty River, from Marsh Leaves, 1895