Featured photographer

Tim Parkin

Amateur Photographer who plays with big cameras and film when in between digital photographs.

Andrew Nadolski was one of my inspirations when I was learning my photographic craft. On a trip to Cornwall, I had read about his 'End of the Land' book and purchased a copy from Tristan's Gallery in Wadebridge (which seems to be shut now). The pictures within blew me away. The range of shapes and composition must have inspired me in some way and I continued to be intrigued by the colour until I finally found out what was going on (yes, sorry, film again).

I was privileged to meet up with Andrew Nadolski on a course I attended in Cornwall and he has kindly agreed to answer a few questions for us about his photography.

How did you ‘get into’ photography in the first place?

I will have to go back quite a few years to answer that. I got my first ‘proper camera’ at 18, a Pentax ME Super. I was doing A-level art at school and started to take pictures but nothing really serious. I had decided I was going to be a graphic designer, so the path was Foundation Course at home in Derby then a 3 year degree course somewhere else. At that stage, I only ever saw photography as a hobby. Also, my views on art were quite blinkered while I was at school; I was really into American Marvel comics and had no interest in fine art at all.

I chose to do a degree in graphic design at Exeter College of Art it because it was the college nearest to Cornwall that offered a degree course. I didn’t know anything about the course structure and didn’t even visit it before I applied, I just picked it on its location. It turned out that the course was based on three main areas of study: typography, illustration and photography, all under a ‘graphic design’ umbrella. In the first year, we rotated disciplines weekly and I found I really started to enjoy the photography projects and working in the darkroom. At the end of the first year, we had to elect to go into one of those three areas. Logically I should have specialised in typography but the photographers seemed to be having a lot more fun with parties in the studios and field trips. There was a girl I fancied who had chosen photography so it was tempting. I talked to the Head of Photography, David Meredith and he told me I could still keep as much typography within my studies as I wanted. My parents were rather surprised when I said I was going to do photography. They were sacrificing a lot financially so I could go to College but to reassure them, I told them having two disciplines would double my job prospects!

I chose to do a degree in graphic design at Exeter College of Art it because it was the college nearest to Cornwall that offered a degree course. I didn’t know anything about the course structure and didn’t even visit it before I applied, I just picked it on its location. It turned out that the course was based on three main areas of study: typography, illustration and photography, all under a ‘graphic design’ umbrella. In the first year, we rotated disciplines weekly and I found I really started to enjoy the photography projects and working in the darkroom. At the end of the first year, we had to elect to go into one of those three areas. Logically I should have specialised in typography but the photographers seemed to be having a lot more fun with parties in the studios and field trips. There was a girl I fancied who had chosen photography so it was tempting. I talked to the Head of Photography, David Meredith and he told me I could still keep as much typography within my studies as I wanted. My parents were rather surprised when I said I was going to do photography. They were sacrificing a lot financially so I could go to College but to reassure them, I told them having two disciplines would double my job prospects!

So you changed direction and you studied photography where one of your tutors was Jem Southam who has worked on the coast and next to water a great deal. Did you find him an inspiration and was he a factor when you started your Porth Nanven work?

It was in the final term of the second year (my first year doing photography) that Jem arrived as a part-time lecturer. He then became a full-time lecturer for my final year. Another part-time lecturer was Paul Graham who had just published his first book: A1 - the great North Road. Both of them would later be seen as pivotal figures in the New British Colour Photography movement. Paul Graham has just recently had a major mid-career exhibition in London.

It was in the final term of the second year (my first year doing photography) that Jem arrived as a part-time lecturer. He then became a full-time lecturer for my final year. Another part-time lecturer was Paul Graham who had just published his first book: A1 - the great North Road. Both of them would later be seen as pivotal figures in the New British Colour Photography movement. Paul Graham has just recently had a major mid-career exhibition in London.

I was really lucky to study at college when I did. I think those were the ‘golden years’ of photography education. The course was full-time, we were expected to be working five days a week, 9am until 6.00pm. Sometimes the darkrooms would be open into the evening or we would decamp to the nearest pub, often with the lecturers, to carry on photography discussions. We lived and breathed photography. I think you need a hands-on approach; you can’t teach people about photography purely in a classroom.

I can see why you ask the question about Jem’s work but when I was being taught by him he wasn’t doing the work you are probably familiar with. He had produced an interesting series ‘Painters of the West of Cornwall’ but I didn’t see him then as a landscape photographer.

The best thing I learnt from Jem, Paul and the other lecturers was to think and conceptualise. Also, they were instrumental in introducing C-type printing in my final year. Prior to Paul and Jem’s involvement (read Jem Southam's articles), we had to shoot on transparency and make Cibachromes, which I hated.

After I had started The End of the Land, Jem who was then the Head of Photography let me use the colour darkrooms at the College to make my first prints. It was at this stage that I saw his stunning work on rockfalls.

After I had started The End of the Land, Jem who was then the Head of Photography let me use the colour darkrooms at the College to make my first prints. It was at this stage that I saw his stunning work on rockfalls.

We’ll be talking about photography in a future video interview but can you tell us briefly how the Porth Nanven project came about?

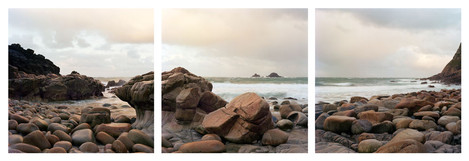

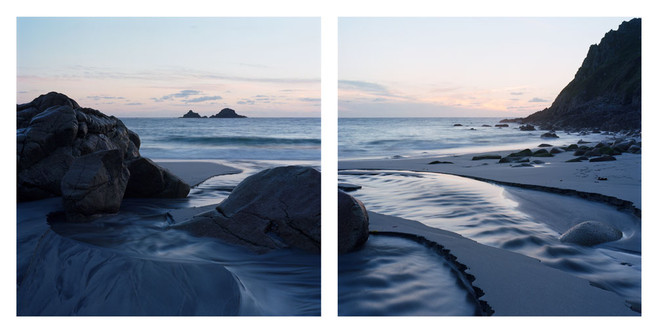

I had been introduced to Porth Nanven by a friend years before, he wanted to show me the stunning raised beach. The reason I started taking photographs there was because of a girl. I had loved and lost someone, who at the time I thought I wanted to spend my life with. I was in a situation that was way over my head. I decided to make her a handmade book of photographs of Porth Nanven to try and win her back. If I go into more details this is going to be more ‘Mills and Boon’ than a discussion about photography. Let’s just say, luckily, it didn’t work as intended.

You have a particular look to your images in The End of the Land. What combination of approach, technique, equipment and post processing do you think is the biggest influence on this?

To adapt a well known phrase of photojournalists; it was a case of ‘f22 and be there’.

My first pictures at Porth Nanven were taken in 1996 so everything about the picture making process was pre-digital. I was shooting on colour negative, selecting from contact prints and then making C-type hand prints when I could beg access to a colour darkroom. I think it was around 2001 that I acquired a Nikon 8000 film scanner; that completely changed my work process. When I started to scan my negatives I was looking for files that matched my darkrooms handprints. Of course, as I learnt more about scanning negatives I realised that I could have some control over contrast which can make beautiful cotton rag prints.

My first pictures at Porth Nanven were taken in 1996 so everything about the picture making process was pre-digital. I was shooting on colour negative, selecting from contact prints and then making C-type hand prints when I could beg access to a colour darkroom. I think it was around 2001 that I acquired a Nikon 8000 film scanner; that completely changed my work process. When I started to scan my negatives I was looking for files that matched my darkrooms handprints. Of course, as I learnt more about scanning negatives I realised that I could have some control over contrast which can make beautiful cotton rag prints.

The ‘look’ you are referring to comes from the fact that I like working with flat light for colour. Also with negative film, it is very hard to blow the highlights, so I don’t work with graduated filters. That was the biggest problem I had when I tried to shoot on medium format digital; I hated having to use grads. The sky would be over dramatic and heavy and I found I couldn’t correct this later in Photoshop in a way that would match a good negative. I know there are techniques of exposure blending and HDR but I find it easier to trust my exposure meter and the film’s tonal range. I think as well trusting your ‘eye’ is important; with digital, there is a tendency to keep wanting to check the screen and ‘see if things have worked’. I found I can’t make those judgements in the field.

For me, my best pictures come when I am working in the simplest fashion. I really don’t want to be thinking too much about technique when I am shooting. It is more important for me to concentrate on what I am photographing and how it might fit into a narrative than worrying about too much about technical matters. I think that is why I have settled with medium format. It has some of the benefits of large format; a ground glass screen to compose on and good enough image quality to make large prints but it allows me to work quickly and try things out and important work in conditions that are sometimes quite extreme.

For me, my best pictures come when I am working in the simplest fashion. I really don’t want to be thinking too much about technique when I am shooting. It is more important for me to concentrate on what I am photographing and how it might fit into a narrative than worrying about too much about technical matters. I think that is why I have settled with medium format. It has some of the benefits of large format; a ground glass screen to compose on and good enough image quality to make large prints but it allows me to work quickly and try things out and important work in conditions that are sometimes quite extreme.

For anyone interested, the majority of pictures in the book were taken on an 80mm standard lens. I used a Bronica SQA for a few years before switching to a mechanical Hasselblad.

Do you think that having an art degree has opened doors for you or do you think you could have managed what you have achieved without it?

I think if I hadn’t gone to art college I would have been technically capable of taking pictures like those in The End of the Land; but conceptually, no. You can teach someone how to take pictures quite easily, especially with today’s technology but learning to think is a different matter.

I think that keen photographers who want to develop their photography further need to think of it this way. They would be better off spending their money on a good workshop than on buying a nice new lens. But when I say a good workshop I mean one run by a photographer who is going to make them think and stretch themselves, not merely a class on how to use your digital camera and the rule of thirds.

I think that keen photographers who want to develop their photography further need to think of it this way. They would be better off spending their money on a good workshop than on buying a nice new lens. But when I say a good workshop I mean one run by a photographer who is going to make them think and stretch themselves, not merely a class on how to use your digital camera and the rule of thirds.

I am getting to that stage in my life when I feel I am ready to pass on some of what I have learnt. It is something I need to explore.

Now that you are known (by many landscape photographers at least) as ‘Mr Porth Nanven’, has the book backfired a little and attracted too much interest to ‘your’ beach?

Not really, how could I begrudge anyone wanting to take pictures there. I think it is a big plus if it people visit that area and spent some money locally. I took Joe on a ‘quick tour’ some years ago. I enjoy showing people where I made the pictures in the book as it illustrates just how much the beach changes over time.

Was there any previous significant work at Porth Nanven that you have found in your research?

Was there any previous significant work at Porth Nanven that you have found in your research?

I hadn’t seen anyone else’s pictures of Porth Nanven; either before I started or certainly during the first ten years of my photographing there, so I was able to develop my own vision. It was important for me that from the outset there was a theme holding the pictures together. The book is meant to work as a poem; it’s just that it is made of pictures not words. Seeing other photographers’ work might have affected this.

Now if I flick though the various photography magazines in WH Smith there always seems to be a Porth Nanven pic in at least one of them.

You have just updated your website (and very nice it is too). Did you design this yourself (I would presume as you are a graphic designer that you did) and did you get someone else to build it or take the task on yourself?

I did it myself. I am primarily a graphic designer for print, though I am getting interested in designing for electronic distribution. Building the website would have been easier if I used templates or got someone else to code it but I wanted to try and build it from the ground up. It helps that I wanted it looking clean and simple. What took the longest was pulling all the images together and finishing all the scanning.

Your ‘I, tourist’ project couldn’t be much further away from Porth Nanven thematically. What connections are there between to the two bodies of work and how did you come to be working in two very different genres?

Your ‘I, tourist’ project couldn’t be much further away from Porth Nanven thematically. What connections are there between to the two bodies of work and how did you come to be working in two very different genres?

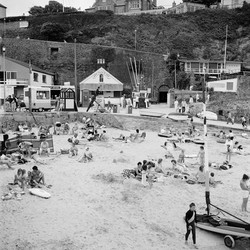

I started photographing in Newquay in 1985 when I was in my second year at Exeter, my first majoring in photography. At this stage in my education I was probably the most ill-informed student there was when it came to other photographers work. I hadn’t done any history of art studies at school and I certainly had no knowledge of photographic movements. What I was beginning to learn though was that it was ‘okay’ to photograph ‘ordinary things’ and that the immediate, everyday landscape around me could be a source of inspiration. One photographer I can remember looking at was Fay Godwin. I think I was interested in her work initially because she shot quite a lot of square images and I had just got a cheap, second-hand twin lens reflex camera.

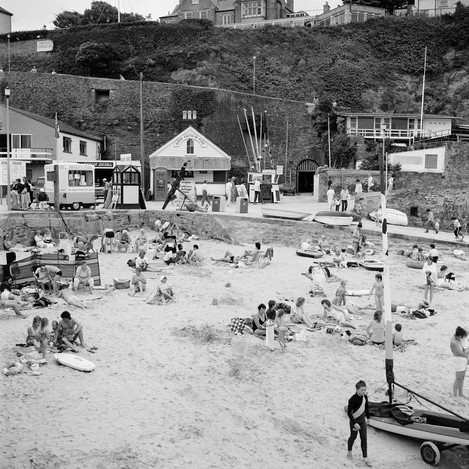

I was spending the Whitsun holiday with friends who lived in Newquay. I needed to shoot some pictures over the break and had initially thought I would do some ‘rocks and water’ pictures like some shots of ice and waterfalls I had done a few months before in the Brecon Beacons. My friends were working during the day and as the weather was really nice I wandered around the beaches of Newquay with my Minolta Autocord TLR. I started taking pictures of the beaches and tourists but the pictures weren’t completely detached and analytical as years before it would have been me and my family on the Tolcarne Beach; my memories were shaping what I photographed.

I didn’t use a tripod. I realised I could hand hold my TLR, compose on the ground glass screen, take a picture quickly and instinctively and then move on.

When I got back to College I showed my contact sheets to Jem and the other lecturers and they were really positive about the images. I can remember them talking about the New Topographers and Joe Deal’s work. I said ’who are the New Topographers’ and ‘who is Joe Deal?’.

When I got back to College I showed my contact sheets to Jem and the other lecturers and they were really positive about the images. I can remember them talking about the New Topographers and Joe Deal’s work. I said ’who are the New Topographers’ and ‘who is Joe Deal?’.

The next year Fay Godwin came and did a lecture at the College. After I had cornered her to sign my copy of Land, I showed her my Newquay pictures and she told me I should carry on with them and that they should be exhibited. However, as it was my final year I started to panic about earning a living and so personal work went out of the window for a while, which I really regret now.

A year or so after leaving College my freelance work increased and I showed the pictures to other people. This led to a portfolio of them being reproduced in a regional arts magazine and then a joint exhibition at Plymouth Arts Centre. When I could, I carried on with the series until about 1991. It was later when I started scanning my negatives and making bigger prints that I found my interest in the series renewed and I started photographing in Newquay again in 2009.

I really like the fact that the series is so different to The End of the Land. I know that the pictures won’t be as popular with a lot of people but that doesn’t really affect how I feel about them. At the moment I am pulling all the strands of a story together which will put the photographs in a wider context. I would like to make it into a book but I don’t know if it would be commercially viable.

I really like the fact that the series is so different to The End of the Land. I know that the pictures won’t be as popular with a lot of people but that doesn’t really affect how I feel about them. At the moment I am pulling all the strands of a story together which will put the photographs in a wider context. I would like to make it into a book but I don’t know if it would be commercially viable.

Your work shows an exquisite eye for composition, something that I find sadly lacking in much ‘fine art’ photography - do you think this is strongly influenced by your graphic design background?

I think it must be on a subconscious level but I don’t actively think about things like the rule of thirds; which I never bothered learning about. I compose instinctively. I think working on a ground glass screen and left to right juxtaposition sometimes ensures the image balances really well. I know large format photographers say having the image upside down on the screen benefits them even further.

I have learned in over 25 years of taking photographs that who I am and how I see things is what makes an image work ,not a technique. The more I can simplify how I work ‘in the field’ the more successful the photograph.

The new website that Andrew has built is live now so go take a look at http://www.nadolski.com and Andrew has also kindly supplied us with larger versions of his images for your pleasure.

Andrew Nadolski was born in Derby in 1964. He lives in Exeter and works as a photographer and graphic designer. Signed copies of the End of the Land are available from Andrew directly at £25 including p&p (Normal book price £29.99).

Please contact Andrew on 01392 496200 or email andrew@nadolski.com.

Payment via credit card, paypal or cheque