Eliot Dudik

Eliot Dudik

Eliot Dudik is an American photographer and book artist with works in institutional and private collections across the globe. His long-term projects, books, and collaborations explore the connection between culture, memory, history, and place. His first monograph, ROAD ENDS IN WATER, was published in 2010. In 2012, Dudik was named one of PDN’s 30 New and Emerging Photographers to Watch and one of Oxford American Magazine’s 100 New Superstars of Southern Art. He was awarded the PhotoNOLA Review Prize in 2014 for his BROKEN LAND and STILL LIVES portfolio, resulting in a book publication and solo exhibition.

His unique and interactive book COUNTRY MADE OF DIRT (2017) was recently acquired by Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, and Duke University’s Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Dudik produced two collaborative books in 2018: NOTHING THAT FALLS AWAY with Meg Griffiths and Zatara Press and AND LIGHT FOLLOWED THE FLIGHT OF SOUND with Jared Ragland for One Day Projects. Dudik’s work will be included in the Mulhouse Biennial of Photography at the French Cultural Center in Freiburg, Germany during the summer of 2018.

Dudik is based in eastern Virginia, between Richmond and Williamsburg, where he manages his active photography and book arts studios. He founded the photography program within the Department of Art & Art History at the College of William & Mary in 2014 where he is currently teaching.

Charlotte Parkin

Head of Marketing & Sub Editor for On Landscape. Dabble in digital photography, open water swimmer, cooking buff & yogi.

I've followed Eliot's work since Steve Coleman interviewed him back in 2015. Eliot's work has been prolific since then, working on different collaborations and projects, whilst exploring different mediums for expressing his work; from handmade books, printed books, and his most challenging project "Country Made of Dirt". His passion for analogue photography is impressive and he has recently set up The Film Photo Award which is to highlight the dedication to the film photographers pushing the medium forward in the 21st century.

Steve Coleman interviewed you back in 2015 and it looks like you've had a prolific creative period since then. What has inspired this? Are you always so productive or has this been an exceptional time for you?

I'm plagued with the gene that makes me constantly try to squeeze 30-minute tasks into 10-minute slots. I suppose we all have that to a certain extent today. I'm not sure if this is an exceptional time for me, but I try to remain productive every day.

Tell us about the project Country Made of Dirt. How did it come about, how did it evolve, and how did you go about collaborating with Arielle Greenberg? The final construction is an artefact in its own right - is the method of viewing part of the intended experience from the start?

Country Made of Dirt is certainly my most challenging book construction to date, which is curious because it was born from pure play. I taped a new Carl Zeiss digital lens to my 4x5 to see what would happen. I was mesmerised by the result, especially as it lay upon the ground glass. An attempt at recreating that viewing experience is what ultimately led to the Country Made of Dirt book project.

With this combination of camera and lens, the front and rear standards of the view camera had to remain completely smashed together, so there were no movements available, not even focus. To focus, I had to ask my subject to physically move forward and back to fall into the extremely thin slice of sharp focus the lens was providing. Because the Carl Zeiss digital lens does not have a shutter, and I was using it with the aperture wide open, I made these pictures at dusk, after the sun had dropped below the trees, which would allow me to extend the exposure time to something I could physically control by covering and uncovering the lens by hand.

After a mild obsession with making these images, I decided to print them in platinum and palladium. I printed them over the course of a year, enough of each image to make twenty books.

Photographs and video of the book and box can be seen on my website: eliotdudik.com

The book 'Nothing that Falls Away' was a collaboration between you and Meg Griffiths about Highway 50, “The Loneliest Road in America”. How do you find the process of collaboration from a creative viewpoint and how did you go about developing your ideas both visually and conceptually?

This is one of several collaborative projects I've worked on recently, as collaboration has been playing an increasingly important role in my practice over the past five years or so. In collaboration, the process of overturning new rocks and discovering the unexpected seems to happen faster and in even more surprising ways because two or more minds are coming together and not only sharing those experiences but also interweaving past experiences in surprising ways. It goes beyond the collaboration itself; I've felt bits of collaborative practice filter into my solo projects too, shifting the way I work and think, and I find that very exciting.

Between books and exhibitions, what do you think is the most important for your work and why?

I engage with both mediums, although I have been focusing a lot of time lately on book projects as much of my work is made with the structure and sequence of a book in mind from the start. I do like the idea of permanence in a book that once it is out in the world it doesn't disappear. It can be revisited; the viewing experience can change over time; new understandings can emerge with prolonged engagement. I'm an obsessed book and print collector too, so I enjoy adding to the conversation and inventory with which I surround I'm not sure one is more important than the other. They both have their place and purpose.

The project “And light followed the flight of sound” was focused on one day rather than other projects where you've worked over a period of time. How did you find this different approach?

And light followed the flight of sound is the latest collaborative project I've done with artist Jared Ragland as part of our One Day Projects. He and I began these projects as an experiment and exercise, not unlike an athlete trains for an upcoming season. We wanted each project we did to be different from the last, but each revolves around the idea of a single day in some way or another. Both Jared and I typically work on long-term project spanning many years, so this collaboration was intended to get us both thinking differently from the very basic structure of the project – what can we do with or about a single day?

The first two books we created focused on the photographs Jared and I made in a single day, and then came back to make-shift studios we had set up, either in New Orleans or Richmond, Virginia, and edit, sequence, design, print, and bind an edition of books. This latest project was different in that we collaborated with a little over 50 artists from across the United States, all of whom submitted some photographs they made on the day of the total solar eclipse that cut across the entire country on August 21, 2017. While our country was (and still is) extremely polarised politically and culturally, on this one day it is estimated that about 90% of the country came together and stared in wonder at the same sky. Jared and I spent the next 18 months editing, designing, and hand making 150 copies of a 30-foot-long accordion book and tipped in zine to complete this project.

This project was planned over a period of time as opposed to 'Nothing That Falls Away’ which was more spontaneous. Which process did you enjoy and why?

I see One Day Projects in general, and our latest book, And light followed the flight of sound as spontaneous projects as well. The spark of the idea comes quickly and intuitively, and slowly the specifics and materialisation arise through consideration and deliberate choices. Nothing That Falls Away happened this way too, so I'd say they were more similar in how they came to be, than different.

The website for the project says "The book’s title references E. M. Forster’s 1909 dystopian novella, The Machine Stops, in which the human species has become completely reliant upon technology to provide sustenance, deliver information, and mediate relationships." How did you go about translating or interpreting a work of art in one medium (novel) into photography?

Similar to our previous books, Bras Coupé and Or Give Me Death, we used references from history, literature, and folklore as points of inspiration from which to begin, or end, our work. Prior to making the photographs for these books, or designing the books, we would read these passages, discuss them, pick them apart, and try to absorb them into our psyche. In so doing, as we go out into the swamps of New Orleans, for instance, the words and images are filtering through our consciousness and sub-consciousness while we work and influencing what we see and choose to photograph whether we realise it or not.

On this project, you edited, designed and produced the project in collaboration with Jared Ragland. How did you find the process of editing and producing? How did you go about conveying your visual idea for the book?

And light followed the flight of sound proved to be the most difficult project Jared or I had ever attempted to edit, sequence, and design because the work was so varied. We collected about 500 photographs from a little over 50 artists. All photographs were made on the day of the solar eclipse, but they were all very different. Some were of the eclipse, many not at all, some were a digital, film, Polaroid, historic process, colour, black & white, etc. Editing to a cohesive set that made sense together and said something larger about our collective experience was very difficult and it took Jared and I many months to complete. We workshopped the editing process with students at several universities that was as helpful to us as it was to them, I'm sure. Ultimately, Jared and I are quite pleased with the result.

What made you decide on the handmade book as the final piece for the project rather than other formats?

This was partly out of necessity ($), partly out of a desire to be in control, and partly because we wanted to. This book is actually a sort of hybrid. We had the pages commercially printed. We managed to secure a small grant from the university I teach at, William & Mary, and that was enough money to cover the commercial printing of the book. But to bind it, have hardcovers made, tuck a zine into a pocket, create the interactive sleeve, this would have cost a lot more money to commercially produce entirely. So, we commercially printed the pages, and then painstakingly sat in an un-air-conditioned art studio in Birmingham, Alabama for weeks and glued individual pages together into 150 copies of 30 foot accordions.

One of my favourite and, in my mind, the most important parts of my practice is engaging with the materials in an intimate and hands-on way. Whether it is the film I'm shooting, printing in the darkroom, bookbinding, frame making, etc., I enjoy engaging materialistically in every stage. It just doesn't excite me to send off a project of any sort, whether a book or photograph and have someone else produce it and send the result back to me in a box. There isn't any reason for Jared and I to do these projects if they aren't exciting us, and for me, I want to physically make the books, that's how I get excited.

The project 'Paradise Road' you started in 2013 and was focused around 'While mapping, travelling, and photographing Paradise Roads located across the United States, my aim is to build a typology of place that visually articulates how Americans’ sense of identity and inherent optimism can manifest in the landscape and to produce a metaphorical survey of American happiness, security, sanctuary, longing, and unfortunately, defeat in this particular changing and imbalanced time.' Is this a project that you have on the back burner and dip into and do you plan specific time periods to work on this project?

It's not so much that it's on the back burner as it is and I'm working on several things simultaneously. I still have many 8x10 negatives that I've made for this series that I haven't had a chance to get on my drum scanner yet. I tend to visit new or revisit previous roads while I'm travelling for other purposes as well. Lately, I've become deeply fixated on the state of Maine, and I've been obsessively working on an expanding project based there. I've found myself working there every summer and winter for the past 5 years, which has curtailed the time I have to work on other projects outside of my teaching. But I am still working on Paradise Road, our National Public Radio (NPR) Picture Show just featured the series a couple of months ago, and there are some new images included there.

You've run workshops on handmade books - what's the appeal of handmade books for you?

I think I've covered this above. But to continue, I've always seen the book as the ultimate, final realisation of an idea. However, getting published is full of challenges and limitations, which is what brought me to study bookbinding to begin with. It brought a lot of things together for me: control over the process, material, design, and quality, engaging with the materials in meaningful ways, and fully committing the finalising process of bookmaking. It is very freeing to take on book production on your own, building the confidence to layout your own edit, sequence, and design, and bring your work up to that threshold without having to rely on anyone else.

Do you think that a desire to hand create real world artefacts is driving people back to old processes of capture and printing and also the handmade ethic?

Absolutely. At least for me it is.

Sequencing is obviously important - how do you manage the flow of the images and visual narrative when you're working on a book. Can you recommend anything you have learned that would help our readers?

I try to start with everything, all possibilities, and slowly narrow the edit down, usually in a give-and-take scenario. Each book sequence evolves differently, but generally, I'll try to start with a beginning and/or end – how do I want the book to start or how do I want it to end? That usually gives me some parameters from which to work – all I have to figure out from there is how do I get from one place to the other. Then I'll try to put together little 2, 3, or 4 picture sequences that I feel have some rhythm to them and address some of the ideas I want to explore in the book. And ultimately, I try to connect those moments and ideas between the beginning, middle, and end.

Does this process differ if it is a handmade book compared to a commercially printed book?

I don't think it does. Although if you're talking about a traditional published, commercially printed book, the publisher is probably going to want to have a say in your sequence and design. That collaboration can be massively helpful, or it could be a nightmare.

Over the various projects you've done in the past few years are there any images that stand out for you for any reason?

There are a number of moments in my new work from Maine that have been new experiences for me, but I haven't yet published any of that work. Soon! From my most recent trip for Paradise Road in 2018 that took me 17,000 miles around the United States, there are several new pictures that I think bring this project to a new level. In general, the pictures from this trip were better than what I had made previously because I forced myself on this trip to be less concerned with efficiency and trying to cover as much ground as possible in as short a time as possible, and instead spend as much time on the Paradise Road as necessary to get to the heart of it. And I did not leave until I felt I had, which wasn't always the case in the past. I often landed on a Paradise Road somewhere, decided too early that there just wasn't anything there, made a picture anyway, and moved on. In 2018, I didn't do that, and the roads that I thought were not fruitful when I arrived, turned out to be some of the most powerful experiences and photographs made on the entire trip.

Paradise Road, Baytown, Texas, Paradise Road, Hermosa, South Dakota, Paradise Road, San Diego, California, and Paradise Road, Lopez Island, Washington are good examples of this. I was lucky to have met these folks, and it was only possible because I forced myself to stay longer, look closer, and dig deeper than what my initial perception of the road was revealing to me.

You have worked on solo and collaborative photographic projects; do you have a preferred approach or do these different styles suit different needs?

I appreciate both approaches. Neither would be what they are without the other.

How do you structure your time? You obvious have creative periods, run workshops alongside your role as Visiting Assistant Professor/Lecturer in Photography: College of William & Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia. Do you work in bursts or have you developed a consistent work ethic?

I'm pretty much always working. I usually have a list of things that absolutely have to be done that day or that week, and I try to focus on those. There is usually so much to be done in a given day or week, that I rarely get a chance to work on anything that isn't due immediately. Someday I will figure out how to change this. It probably has something to do with doing less.

Could you tell us a little about the cameras, film and lenses you have used on these projects? Could you tell us a little about the cameras and lenses you typically take on a trip and how their choice affects your photography?

I use view cameras almost exclusively. I usually have a 6x7 medium format camera with me for less specific things, but my work is usually exposed on large sheets of film. Depending on the project, I work with 4x5 and 8x10 mostly. Broken Land was 8x20. Paradise Road is all 8x10. Still Lives is 4x5. The work I'm doing in Maine right now is a mixture of 4x5 and 8x10. I also just picked up an 11x14 camera that I've been using to experiment with paper negatives. All of my colour film projects use Kodak Portra. I carry a variety of lenses with me for 4x5 and 8x10, usually wide, normal, and long, with some variations in between. I'm not sure it's terribly important to get into specifics on that, I don't really pay a lot of attention to these sorts of things. I tend to get attached to one lens for the 4x5 and one for the 8x10 that I use most of the time, and the others are just there for specific occasions. I enjoy experimenting with combinations of lenses, film formats, and cameras that are not intended to work with one another.

You are the founder of the Film Photo Award, tell us where the idea came from and what you wanted to achieve with this award.

The Film Photo Award is intended to get a large pile of Kodak Professional film into the hands of deserving film photographers who show a dedication to pushing the medium forward in the 21st century. I worked on this project for a number of years with Kodak Alaris before we finally got it off the ground in the spring of 2019. Unfortunately, the Covid-19 pandemic has put a damper on the award programme in 2020, but we have helped produce a number of outstanding projects thus far with the film we have managed to award. Check out some of the Film Photo Award recipients here: https://www.filmphotoaward.com/alumni

Where do you see analogue photography going? Are you seeing more students using film or alternative printing techniques and why do you think this is?

Fortunately, I don't see analogue photography going anywhere any time soon. My students are floored by it. Most of them have never even seen a roll of 35mm film upon entering my classroom. My Introduction to Photography course is completely large format based, which allows them to engage with the practice of seeing, thinking, and composing in hyper deliberate ways. They are forced to make a long series of decisions throughout the process of shooting, developing, and printing, each of which leads them ultimately to an image they had an intimate role in creating. I think they are attracted to that engagement and relationship, the same as I am. When my students ultimately get to my upper level Photography Portfolio courses, where they can choose the medium, materials, tools, processes, etc that make the best sense for the work they want to create, the vast majority of them end up back in the darkroom. I'm teaching a lot of historic processes right now, using the sun, and teaching outside, because of the pandemic. The students love it. None of them would give up their screens, of course, but to have the opportunity to step away from them for a minute and make something with their hands and watch it come to life under the actions of the sun; they're quite thirsty for it.

You studied photography at Savannah College of Art and Design, Savannah, Georgia. How did this experience shape your photography?

I can't explain how powerful this experience was for me. Before entering into something like this, there is no way to fully understand how the experience is going to change you as a human being, and in my case, as an artist. But I know who I was going in and who I was coming out, and those two people are very different from one another. I have the photography faculty there to thank for that, 100%. One of the things I found truly helpful at SCAD was that there were a ton of photography specific faculty. I think there were about 20 photo faculty. This allowed me to get varied feedback from a lot of different types of people and also to gravitate toward certain faculty for certain purposes. I would intentionally take my work to faculty who I thought would hate it and tear it apart. I would also have many options for going to the right person for advice on printing techniques, historic process, view camera techniques, marketing questions, etc. Many colleges and universities have somewhere between 1 and maybe 3 photo faculty, so having this variety at SCAD was super helpful. A number of the faculty I worked closest with remain dear friends of mine today. They also have incredible facilities.

Your work explores the connection between culture, memory, history, and place. Has this always been this way or was this something that has developed over time?

I think it has always been there, but it has been nourished and expanded in various ways. Some play a larger role in some projects more than others. I tend to gravitate toward the landscape. Most of my projects begin as landscape projects and either remain that way or sometimes expand into more. I studied Anthropology and Art History as an undergrad, intentionally to influence my understanding of the world and my photography. I continue to study every day, so my relationship with these things and their influence on my work is certainly evolving.

Do you develop and scan the film yourself? Do you enjoy this part of the process?

I usually send my colour film off for processing to Griffin Editions in New York City, but I've always scanned my own work. Of course, I develop my own black & white film and make my own silver prints. I do enjoy this part of the process as much as any other. It's getting a little overwhelming these days with so many things happening at the same time, and I've considered bringing in some help, but I have a hard time imagining someone else doing part of the work that I feel is so integral to process, and ultimately the understanding of the work. I'm not sure, we'll see. It would probably be healthier for me to try and let go a little...

Tell me about the photographers or artists that inspire you most. What books stimulated your interest in photography and who drove you forward, directly or indirectly, as you developed?

Goodness, as I said above, I'm an obsessed book and print collector. Certainly, each one of these 100s of volumes and countless others I don't own have influenced me over the years. I can say that Joel Sternfeld was one of my biggest early influences, first with American Prospects, then Walking the Highline, and then Oxbow Archive. These books just knocked me flat. They had a massive impact on the way I thought about a photographic project and they are what first got me hooked on holding a photography book in my lap. I began collecting with these books, and it has become a huge problem since then.

Another problem I have is that I'm interested in an enormous array of photography types. I don't just collect books by photographers who make work similar to me. I'm looking at all kinds of things that are far from what I do, and in many ways, I often appreciate that work more. Some photographers I can't get enough of lately are Thomas Locke Hobbs, Jordanna Kalman, Barbara Bosworth, Raymond Meeks, Justine Kurland, Deanna Lawson, Sam Contis... this just goes on and on. Chris Killip passed away the other day, and I've been revisiting a bunch of his work. What a massive loss. He was so damn good, and just a massive influence on photography over the past 50 years.

What is next for you? Where do you see your photography going in terms of subject and style?

I wish I knew the answer to that. I'm still really focused on the work I'm doing in Maine and I hope to start releasing some of that soon. I've just begun a new chapter on that work, which has probably another couple of years of work in it. In the meantime, I hope to find some time to get into my book studio as much as possible and see what I can come up with. I haven't made a book since 2018, and I'm itching to get in there.

- Country Made of Dirt

- Country Made of Dirt

- Paradise Road, Baytown, Texas

- Paradise Road, Eagle Creek, Oregon

- Paradise Road, Edgemont, South Dakota

- Paradise Road, Hermosa, South Dakota

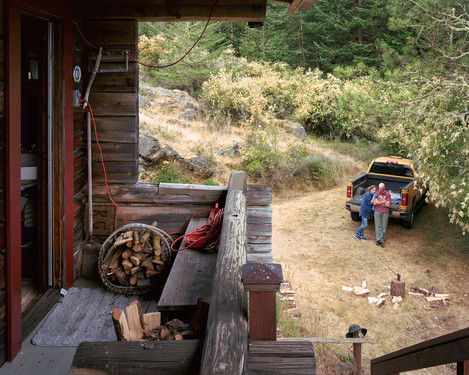

- Paradise Road, Lopez Island, Washington

- Paradise Road, Medina, Ohio

- . Paradise Road, San Diego, California

- Paradise Road, San Simon, Arizona

- Paradise Road, Tracy, California

- Paradise Road, West Augusta, West Virginia

References

https://onedayprojects.org/and-light-followed-the-flight-of-sound

https://www.analogforevermagazine.com/features-interviews/interview-2019-film-photo-award

https://wmrocketmagazine.com/2019/06/06/eliot-dudik/