An excursion through the Taunus mountains

Xavier Arnau Bofarull

I am an amateur photographer based on the Taunus Range, a mountain near Frankfurt am Main, Germany. I have no formal training in either art or photography. Since five years I try to improve my skills on Landscape Photography, and as a member of a Photo Club I took part in some Exhibitions.

A culture is no better than its woods.~W.H.Auden

During an excursion through the Taunus mountains, I passed through one of the many beech woods that cover the mountains. It was a cold winter's day, shrouded in a low layer of clouds that gave the landscape a deep purple colour, and the thin layer of snow that had fallen the night before was barely visible.

In this somber and melancholy landscape, the silent beeches rose black as the skeletons of a cathedral in ruins. My boots splashed through the thick mixture of snow and mud on the road, and I heard the echoes of a few creaking noises that softly broke the silence around me. I looked towards the tops of the trees and saw that they were swaying restlessly, getting closer and then moving away.

I was apprehensive, remembering some scientific article that explained that trees are capable of communicating with each other and reacting collectively to threats and aggressions from their surroundings. At that moment, I thought that the beeches, like a herd alarmed by a threat, were shifting nervously, warning each other of the presence of a danger, which was none other than myself, a human being – the species responsible for centuries of mass destruction of the woods – who was entering their territory. Small and alone as I was, I was anguished at being seen as a danger by the trees.

My relationship with the Earth has changed substantially over the years – due, among other things, to my love for landscape photography –and since that excursion, my relationship with trees has changed even more.

Science has contributed knowledge about the sensitivity and intelligence of the different living beings on Earth. While in the 1970s, I was sceptical about the assumption that talking to plants helped them grow more healthily. Today, I talk to them while watering them, just in case.

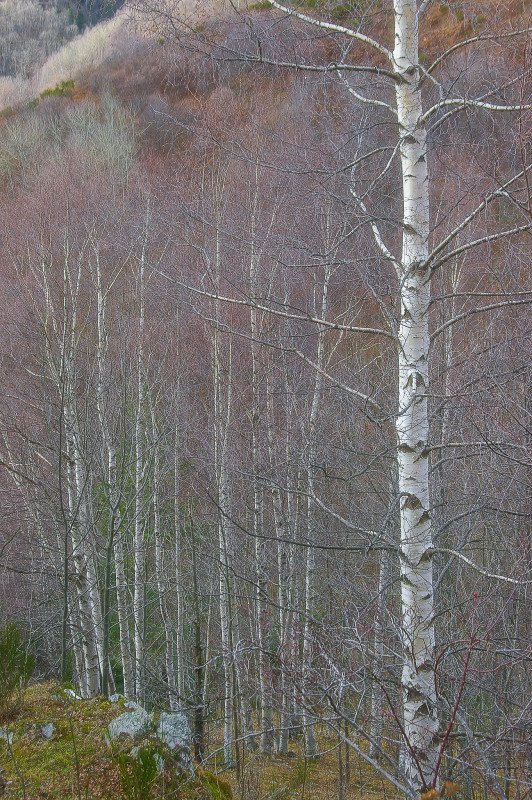

So, when I go on an excursion to take photos, in order not to cause any fear among the trees – real or imaginary, who knows – as I thought I had done on that winter excursion when I enter a wood, I usually murmur a greeting, whistle in reply to birdsong and, from time to time, rest the palms of my hands on the rough bark of an oak or elm, on the smooth bark of a beech or poplar, or on the fascinating bark of a birch tree.

In short, rites of peace, rites of concord between species. Perhaps Claude Lévi-Strauss was right when he wrote, “It is therefore better, instead of contrasting magic and science, to compare them as two parallel modes of acquiring knowledge.”

Once the trees have been warned that I come in peace, I walk quietly and with a certain reverence among these still, silent beings, and I try to capture their beauty, harmony and dignity with the camera as they appear before me. I cannot avoid a tendency to romanticise them, as suggested by Novalis when claiming that the world had to be romanticised, “giving the ordinary a superior meaning, the vulgar a mysterious aspect, the known the dignity of the unknown, the finite an infinite appearance.”

I like to go on these photographic excursions where the trees live, especially in autumn and winter, when the fog and snow take over; I enjoy the silence and the light, whether I am taking photos or not. And like the trees, I have the patience necessary to enjoy their company. But, despite everything, I can't help returning from each excursion with a certain elegiac feeling.

Snow and Fog

On days when the landscape is covered in mist and snow, I prefer to walk around the edges of the woods rather than go into them.

These border spaces constitute, in these circumstances, a dual, ambiguous, inert world. On the one hand, the veiled shadow of the forest huddled together like a fearful herd; on the other, the tide of imprecision that runs through the landscape, greatly simplified, now revealing and now hiding the shadows of solitary trees. We will never know if they were dissenters and heterodox trees expelled from the forest or hermits and anchorites that sought another life in those translucent spaces.

Silence

In protected natural spaces (protected? from what? As absurd as it may seem, from us), silence subtly permeates the remote depths of the woods, a silence that any creak, echo or murmur turns into an almost tangible substance.

Walking aimlessly through these woods, sometimes, very occasionally, one has magical, almost metaphysical encounters with arcane totems: the still-upright trunk of a dead tree in a corner of a clearing, suspended in the middle of a gesture whose meaning we do not know; a broken, twisted tree, embalmed with mosses and lichens, already oblivious to the life that continues around it; a tree in a shady corner lying on a mound of fallen leaves, as if waiting with infinite patience for the mourners at its funeral.

In those encounters, silence becomes a feeling that invades and overwhelms us.

Light

During the winter, the trees and woods plunge into a shadowy, distant, silent state. Not even the snowfalls – scarcer and scarcer each year – manage to give the forest a less gloomy appearance.

Sometimes, however, there are moments of revelation. The forest becomes the mirage of a fantastic Gothic cathedral. Beech, oak, birch and spruce trees become sharply outlined columns that ascend vertiginously to support with their branches – for a few moments vaulted ribs and arches – a dome of weightless, diffuse light.

In these brief moments, the light reverberates between the trees, and the passage of time is suspended in the midst of a serene silence. And in the most remote corners of the forest, there are glimpses of chapels that house sylvan idols, whose meaning we do not know.

Patience

From time to time, on excursions, I come across specimens of huge trees. Although their shapes are very different, depending on the type of tree, whether beech, oak, chestnut, pine or spruce, their bearing is truly impressive. When I look at those very tall trees, which are venerable, old and enormous and have branches that give them the appearance of fantastic beings, I think of Hermann Hesse's words about patience, the passage of time and silence: all development, all the beauty of the world needs time, and is based on patience and silence.

Elegy

Sometimes I walk through landscapes traversed by a breath of despair, in which time and space swirl in phantasmagorical whirlwinds that are barely perceptible and must be the timeless gazes of the lost souls of the trees that inhabited those landscapes, agitated and in pain because of what those landscapes were, and are no longer.

Translated from Spanish by Catherine Ann Ryan