Review of Paul Wakefield's new book

It might seem odd to be reviewing a book which, self-evidently, is full of documentary photography, not landscapes. But this is no ordinary photo documentary book; its creator, Paul Wakefield, is unquestionably one of the world’s greatest landscape photographers. And for that reason, if no other, it is a compelling work for On Landscape readers.

I admit a strong personal interest. Paul and I met for the first time at a National Trust photographer’s social gathering in London in the early 1990s. I already had all his books, co-authored with Jan Morris, and was more than a little overawed to be speaking with someone whose work so inspired me. Oblivious to my nerves, Paul was keen to talk about his personal documentary work in India. He intended, he told me, to make it into a book.

I recall then that he didn’t really see this work as especially distinct from his landscape photography. His landscape work, his commercial work, his documentary work was in a sense, all personal. But in India, he did forgo his beloved 5x4 inch Ebony and shoot, as he explained then, with a mixture of Leica and Fujifilm 6x9 (fixed lens) cameras. No one I knew shot digital at the time, and his use of colour negative film was probably the biggest revelation.

Paul and I have met several times since, and the India work has come up occasionally in conversation. But it did seem as if, like many photography passion projects, this was one that might never see the light of day.

So it was with some surprise that we sat down to coffee together a couple of months ago, and he showed me the first copy off the press of Signs of Devotion, a body of work that started in the 1980s and was essentially completed by 2001, over twenty years ago.

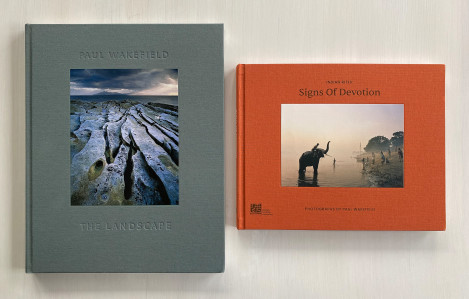

Anyone who has his book, The Landscape, will know the standards Paul has set for design, printing, paper quality, and binding. If anything, Signs of Devotion perhaps surpasses it. The paper is an unusually heavyweight, textured (coated) stock, well-matched to the style of the images. He has a knack for finding special writers to work with, such as Jan Morris in his early books and Robert Macfarlane in The Landscape. Sara Wheeler’s beautiful essay opens Signs of Devotion, and combined with Shrivatsa Goswami’s excellent introduction, these written contributions raise expectations as we move into the photographs.

Yet, even so, the photographs exceed them. The precision and purpose of Paul’s pictures give his scenes and subjects the same significance and depth as a Renaissance painting. This analogy might seem odd, given that late 20th century India is a world away from 16th century Florence, Venice, or Flanders. But the curious, hazy softness and warmth of the light, presumably a combination of heat, dust and humidity, along with the dense fabric of his compositions, make this comparison unavoidable.

Photography and painting do have plenty in common, but the practitioner in each art has to know the particular strengths and limitations of their medium. Self-evidently, photography has to prioritise the unfolding reality in front of the camera. In Paul’s case, his sense of timing, space, and the choreography of figures remind us that he is, first and foremost (perhaps I would say this) a landscape artist.

Because he sees and thinks with a landscape photographer’s sense of positioning, perspective and eye for detail, these images have a richness and complexity that rewards the attentive viewer more than any other documentary photographs I have seen. Almost every picture seems packed with incident and detail, all of it observed, noted, included – framed – because it represents something of the essence of life on the street (as it mostly is) in India. The viewer can revel in the process of interpreting the story in each one as if approaching the end of a particularly engaging jigsaw puzzle.

It is often said that painting is an additive art (defined by what is put in) while photography is subtractive (defined by what is left out). Yet Signs of Devotion is filled with many images that seem defined by what is left in. However trivial or random small objects, shapes and surfaces might seem, in these compositions, they contribute to the whole. They are evidence that everything matters, that humanity and other animals exist in – and depend on – the incidental texture of everyday reality.

The work proves the importance of immersed observation. It is as if the photographer has become part of the place and the moment, lost in the daily tasks, duties, and often chaotic social interactions and events that make up the mystery of the Indian street. Some of the images defy our sense of what composition is, and yet they work due to their tension and balance (pp. 23, 28, 66). It is important to remember that although the work was completed some years ago, it represents hundreds or even thousands of hours on location with the camera.

For sure, he must have made thousands of photographs in India, and Paul’s final selection no doubt leaves out many more wonderful images. The final sequencing is understated and based on visual compatibility, which is sometimes geographically specific. For the most part, the viewer may draw their own story from the page pairing and the overall flow. I have been happy to browse through again and again, spotting previously unnoticed details or marvelling at the human stories that play out on the streets and riverbanks of India. Each photograph is worth spending time with. Some, pages 11, 19, 21, 45, 46, 52, 67, 78, 89, verge on the miraculous.

Most photographers have more than a passing interest in method and technique, but when that method is almost completely invisible because the images are so absorbing, then that is the greatest technique of all. It’s tempting to comment on Paul’s understanding of the colour characteristics of negative film and the visual consistency of limiting his approach to a couple of lenses at most, but really, none of that seems to matter.

What does matter is the sense of time, or perhaps, an absence of it. Sara Wheeler’s essay is entitled, a Hand to Catch Time, an idea echoed in the orange hand print that fills the page before the photographs begin. There are dates on all of the photographs in the excellent catalogue pages at the back of the book, but there is little to indicate that the date was 1992…or 1892…or possibly 2092? This must be an illusion… a local would notice changes that have happened, clothing and transportation, for example. But surely many of the scenes, and especially the rituals observed, were the same five hundred years before and, with luck, will be in another five hundred years. As with all photography, Paul’s Leica may indeed have caught a specific moment in time, but somehow, the images defy time’s gravity.

The work is so compelling that we are left wanting to know more. I was lucky to have Paul talk me through the background to a few, but he has left the captions in the catalogue very simple, just place and year date only. Such minimalism leaves much to the imagination. But it would also be good to know more of the circumstances behind each image. Or perhaps some of them, anyway.

I have only been to India once, in 2010, and then to Ladakh, that Himalayan stronghold in the far north of this gigantic country. It probably isn’t typical of India and so I came to this book with little personal history, insight, or preconception of what to expect. Reading the excellent introductory essays and, above all, having feasted on the images has helped me feel I have made an inner journey there.

I’d like to finish by quoting from Shrivatsa Goswami’s final passage in the book itself:

Paul Wakefield has properly walked upon this path of seeing. He has seen the vast field of Indian rites as they are. His eye behind the camera has received, rather than imposed itself on the seen. His absence allows the seen-scene to fill the frame. He has immersed himself in this cultural space. His devotion to untainted truth and beauty makes it possible for ordinary moments to speak for the extraordinary. His pictures depict life as it is; from courtyards to market lanes, animals to trees, temples to festivals. Paul has allowed his seen subjects to speak for themselves.

I wish I’d written that!

Paul’s book is available on his website. It is, naturally, highly recommended!