Creating a universal language

Keith Beven

Keith Beven is Emeritus Professor of Hydrology at Lancaster University where he has worked for over 30 years. He has published many academic papers and books on the study and computer modelling of hydrological processes. Since the 1990s he has used mostly 120 film cameras, from 6x6 to 6x17, and more recently Fuji X cameras when travelling light. He has recently produced a second book of images of water called “Panta Rhei – Everything Flows” in support of the charity WaterAid that can be ordered from his website.

It is clear that there is no classification of the Universe not being arbitrary and full of conjectures. The reason for this is very simple: we do not know what thing the universe is.~Jorge Luis Borges, from The Analytical Language of John Wilkins

Inspiration comes in many forms. In this case, it was reading The Ongoing Moment by Geoff Dyer that provoked an idea. Dyer, right at the beginning of the book cites the Jorge Luis Borges short story called The Analytical Language of John Wilkins1. In that story, Borges describes different attempts to create a language that would define a classification of things by the nature of how the language is itself structured. John Wilkins (~1614 to 1672) was a natural philosopher, a founding member of the Royal Society of London, and eventually the Bishop of Chester2. He made an attempt to create a universal language and related system of measurements (similar to the metric system in being based on powers of 10). That is not, however, the focus of attention here. The extract relates to Borges’ description in the story of the Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge. This, he suggests, is a certain Chinese encyclopaedia in which it is written that the world of the animals can be classified as follows:

- those that belong to the Emperor

- embalmed ones

- those that are trained

- suckling pigs

- mermaids

- fabulous ones

- stray dogs

- those included in the present classification

- those that tremble as if they were mad

- innumerable ones

- those drawn with a very fine camelhair brush

- others

- those that have just broken a flower vase

- hose that, from a long way off, look like flies.

A perfect and all-encompassing classification (perhaps I will have to go back to Borges – I have never really been a fan of magic realism but his classification is wonderful in the literal sense of the word). The inspiration, of course, was then to think about how we might classify landscape photography in a similarly wonderful way. Indeed, it turns out that we can directly borrow the categories of the Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge, but some need a little modification. Here, then, is a first draft (with some commentary and a little judicious twists of meaning). As in the original, the classes overlap to some extent.

a) those taken by Ansel Adams

Ansel Adams (1902-1984) can surely be regarded as the emperor of influencers in landscape photography – at least for a certain period of the 20th Century. Emphasis on technique and “natural” landscapes (sparking a reaction in what came to be called the New Topographics movement) but providing a framework for educating photographers (particularly in his books on The Camera, The Negative and The Print, which are still in press in the 1995 editions revised by Robert Baker). Less convincing in colour. His influence persists today – at least for those working in (or imitating) monochrome large format.

b) those embalmed in museums

One definition of embalmed is the sense of being fixed for the foreseeable future. For photography that can be interpreted as prints that are being curated and stored under ideal conditions for their preservation (images stored on vulnerable digital media really do not come under this category). Such embalmed images include notably again Ansel Adams and other celebrated photographers in the collections of the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington. Other important permanent collections of historical landscape photography can be found at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Musée de l’Élysée in Lausanne, and the Art Institute of Chicago. Ansel Adams actually produced what he called Museum Sets of some of his most popular prints, with the intention that they should be sold (at a discount) only to Museums or to buyers with a history of donating to Museums or Educational Institutions. These constraints were embodied in a contract that also applied to subsequent owners. Images from the photographers commissioned by the US Farm Security Administration in the 1930s (including Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange and Arthur Rothstein) are held in the Library of Congress (see (g) stray dogs below).

c) those that have trains

One of many sub-genres of landscape photography (see (l) below). Even if the train is the main object, rather than the landscape itself, if the train is not too prominent then the landscape might be of greater interest (to some of us) – though lighting and framing will be constrained by when and where a photogenic train (often with a steam locomotive) actually passes a location. Experience on the Settle to Carlisle line suggests that this sometimes involves the dangers caused by groups of fast moving cars on narrow roads as train photography enthusiasts try to get between prime locations faster than the train.

Landscape with train: A fleeting appearance of the sun coincided luckily on 21 May 2022 with the passage of the southbound Cumbrian Mountain Express hauled by 46115 Scots Guardsman on the approach to Ais Gill summit on the Settle-Carlisle line in Mallerstang. The distinctive mass of Wild Boar Fell dominates the scene; the train has just climbed up the shoulder of the fell along the Eden valley, which separates Wild Boar Fell from Mallerstang Edge. Photo by John Cooper-Smith (with permission).

Similarly applies to some other sub-genres, such as wildlife photography, though the subject is often much too prominent, and the landscape is ruined by being out of focus ….

d) suckling pigs (recipes)

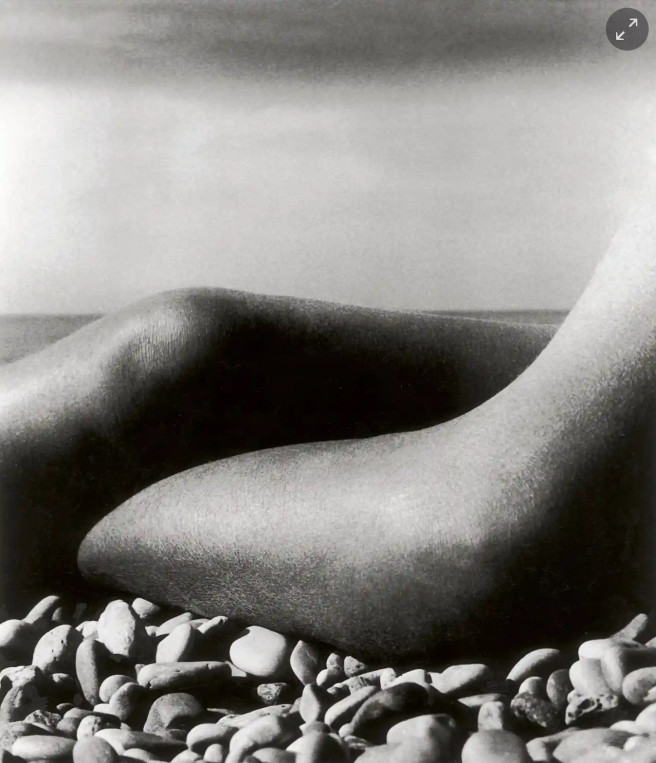

e) mermaids

There are, of course, many examples of mermaids with little or no clothing photographed in the landscape. Most examples tend not to show the fishy tail (although, rather peculiarly, photos of mermaids with fishy tails appears to have become a sub-genre of portrait photography for which there are also instructional videos on YouTube). More generally, this class comprises of landscapes featuring nude bodies, a topic that has attracted many celebrated photographers including Edward and Brett Weston (1886-1958 and 1911-1993), Bill Brandt (1904-1983), and Jean-Loup Sieff (1933-2000). As with train and wildlife photography, this will often detract from the landscape, but in some cases, the light and shade on the forms of the nude become the landscape, as in the ultra-wide angle images of Bill Brandt.

This has now been taken to extremes, of course, by the landscapes of Spencer Tunick (b.1967), featuring hundreds or even thousands of naked people, such as his images on the Aletsch Glacier taken in conjunction with a Greenpeace campaign about glacier loss3.

f) fabulous ones

This is an important category. There are many fabulous landscape images in the sense of being excellent, but perhaps more interesting are those in the older definition of fabulous as imaginary. The use of imagination, of course, implies photographic Art, which might be interpreted in two senses: (i) there is the sense in which an image is post-processed to be unrecognizable from the scene that was before the camera (sky replacements, object removal, overuse of the saturation slider, or adding snow leopards into Himalayan landscapes4, etc); (ii) there is the sense in which the photographer wants to convey his image of the unseen characteristics of the object photographed (essence, metaphor, Borges’ magic realism, etc). We could say that this category, therefore, represents photography as performance (see also the comment on synthography under h).

g) stray dogs

Stray dogs perhaps appear more commonly in the genre of travel photography but, as with trains, can often have remarkable landscapes in the background (there are apparently over 9500 stray dog images on Getty Images and over 35000 on istockphoto.com). Some celebrated stray dog photographs are listed here5, including that of the Parc des Sceaux, Hauts-de-Seine, by Joseph Koudelka (b.1938) in 1987.

h) those that are included in the present classification

This class is evidently self-reflexive. Considering the classes as sets, then in set theory, it is completed by class (l) below to include all landscape photographs ever taken and hence implying some redundancy (see under (j) below).

Those that are not included in the present classification should perhaps include the special category of “synthography” in which digital landscape images are created by computer programs that have gone feral given some descriptive text input6.

i) those that tremble as if they were mad

This class clearly refers to photographers who use intentional camera movements (ICM)7. Unintentional tremblings have in the past few years been greatly reduced by the implementation of in-camera and on-lens image stabilisation.

j) innumerable ones

This class has evidently grown dramatically in the age of digital and smart phones, now that everyone and his monkey can be considered to be a photographer. This has led to the production of innumerable redundant images in the sense of the philosopher Vilém Flusser8 (1920-1991), notably of course of sunrises and sunsets but with an unfortunate tendency for the landscape to be obscured by the photographer standing in front of it.

k) those spotted with a very fine camel hair brush

Many of you will not remember but this is a hark back to the pre-digital age when many hours were spent after sessions in the darkroom with brush and ink to obscure the effects of tiny dust spots and blank spots in the negative on the final print. This was an important (and time consuming) skill in producing exhibition quality monochrome prints.

a) others

This class clearly exists just in case we missed anything important. We can include here a number of sub-categories including:

- those with swirly bokeh

- those with a milky way in a blue sky and a foreground taken earlier

- those with the sounds of cow bells

- those with an aurora

- those with Buachaille Etive Mòr

- those on repeat

- those that are panoramics

- those with slot canyons

- those with centred horizons

- those with more than a rock

- those with shipping forecasts

- those on repeat

- those with red-filtered black skies

- those of rivers and sand bars taken from the air

- those taken in subglacial caves

- those with circular star trails

- those with Aspen trees in autumn

- those with red lava at dusk

- those with hoar frost

- those with a clump of wild flowers in the foreground

- those with the rule of thirds

- those that only exist on Instagram, immediately forgotten

- those with trees in mist

- those with the colours of Landmannalaugar

- those with blurry water

- those with resonance

- those with the golden ratio

- those with black Deadvlei trees

- those where all the ice has melted

- those with the descending call of curlews in spring

- those that sell

- those on repeat

m) those that have just broken a link with the real

With this category we have to be somewhat circumspect since it has been generally agreed in the discussions in On Landscape that no photograph can be considered as real (except in the sense of being a physical artifact). While some representations might be considered more real than others to the viewer (possibly even those synthographics generated by ignorant computer programs), perhaps we should say no more (but see the category of fabulous ones above).

n) those that from a long way off look like a photographic workshop

or multiple workshops gathered together in a classic location with photographers in serried ranks, tripod to tripod, all disappointed that the light is not as good as in the photos they have seen of the same location (e.g. Mesa Arch, Horsetail Falls, Jøkelsàlen, etc). Something best viewed from afar and avoided. Has been a major mechanism of relatively unknown places evolving into classic landscape photography locations, before the workshops move on to something new (from Iceland to Lofoten, to Greenland, to the Lencóis Maranhenses in Brazil, to …)

That seems to have covered just about everything but if you think that some other categories should be added, then please make suggestions in the comments.

References

- A translation by Lilia Graciela Vázquez can be found at https://ccrma.stanford.edu/courses/155/assignment/ex1/Borges.pdf

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Wilkins

- See https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2012/07/the-naked-world-of-spencer-tunick/100344/. For a discussion of glacier loss see https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2021/05/loss-in-the-landscape/

- See https://petapixel.com/2022/11/28/photographer-admits-that-viral-snow-leopard-photos-were-fake/

- https://www.rashedhaq.com/blog/2022-3-7-stray-dog-photographs

- See discussions in Tim Parkin’s article https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2023/02/a-look-at-ai-image-generation

- E.g. https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2020/06/icm-first-attempts-new-unknown-direction/

- See again https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2020/06/landscape-and-the-philosophers-of-photography/

- See https://fstoppers.com/animal/court-ridicules-peta-monkey-copyright-selfie-case-settled-244597 and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monkey_selfie_copyright_dispute