An interview with Gregor Radonjič

Gregor Radonjič

Gregor Radonjič lives and works in Maribor (Slovenia). He's been creating and exhibiting photographs since the early 1990s. His biography includes 33 solo exhibitions, over 60 group exhibitions abroad and in Slovenia, three published books and several multimedia performances. He was selected twice in the programme of the Slovenian Month of the Photography Photonic Moments and the Festival of Photography Maribor and twice in the gallery selection for the Art Photo Budapest. In past two decades and half he has won several national photographic society awards and has been nominated as honorable mention photographer in several distinguished world contests.

Charlotte Parkin

Head of Marketing & Sub Editor for On Landscape. Dabble in digital photography, open water swimmer, cooking buff & yogi.

Alexandra Wesche interviewed Gregor back in 2022 about his project Drevesa. When Gregor approached me regarding his newest book, my curiosity was piqued, especially considering its prompt release following his previous work. Some photographers take years to craft a second book, so I was eager to delve into the details of his Misplacements project and gain deeper insights into the images.

The book's theme is making images featuring man-made objects that have been abandoned or have outlived their original purpose and photographed in the natural environment.

Alexandra Wesche caught up with you back in 2022, talking about your previous projects, Metascapes, Almost Invisible and ‘Drevesa’. What have you been working on since then?

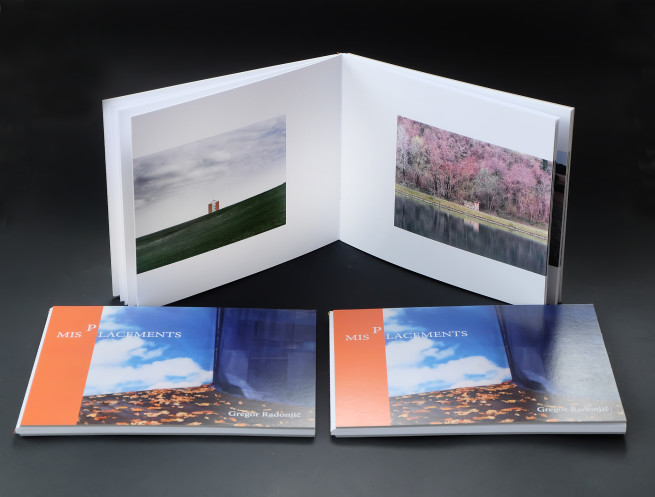

I continued with the Metascapes project, which is actually an ongoing project. Since the last interview, I prepared two solo exhibitions and was selected for the group exhibition of contemporary Slovenian photography NovaF in May 2023. However, the favourite project that I have realised during this time is definitely the release of my last photobook, entitled ‘Misplacements’ published in a limited edition. Not only are all photos my work, but I also designed the book entirely myself and self-published it.

Your new project, Misplacements, you have been working for 12 years. Tell us about how the project came about and the challenges of finishing the project.

It's true; the photos were taken over a period of 12 years. However, the final work, including all design aspects, took place in 2022 and 2023.

The project arose spontaneously after many years of photographing man-made objects that are either abandoned or have lost their original function and which are placed in the natural environment. In the beginning, I photographed such objects at the locations where I happened to be. Eventually, I got the idea to combine them into a photobook with a bit of an unconventional landscape photography concept. The fact is that there are not many photo books with a similar subject.

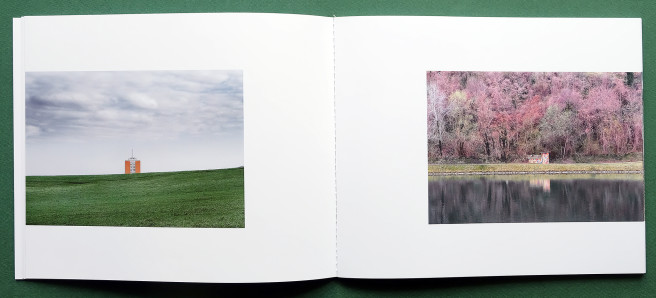

The pairing of photographs was an extremely important part of the creative process. Later, I also spent a lot of time trying to find a really good printer, especially someone familiar with unconventional book binding techniques. I wanted the book's overall look to be unique.

You wrote in the introduction of your photo book, “The traces of human activity are evidence of our presence, and human interaction with the natural landscape is diverse. Sometimes it is more, and sometimes it is less visible. This series questions how we interact with the natural environment by placing isolated man-made objects of different forms and functions into a particular landscape so that its transformation is neither very obvious nor visually too destructive.” Tell us more about this statement. What was it what drew you to start the project?

The photos show man-made objects whose purpose is no longer clear, or they have lost their function but are still present in the natural environment.

In this sense, we could talk about some form of pollution of the natural environment, but as a photographer, I was interested in something else. Namely, what kind of visual effect do these alienated objects have in a space surrounded by nature? This idea unites the whole concept of the photobook. I am interested in the landscape not only as documenting the beauty of nature but also as a place where interaction between nature and human influences is present.

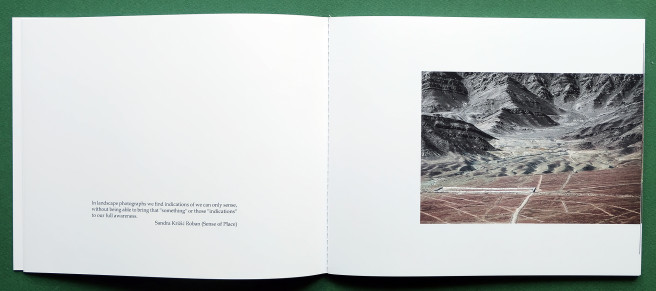

Because I am dealing with 'misplaced' objects, I also decided on an unusual design solution and placed the photos mostly on the outer edge of the page or close to the gutter, with which I wanted to emphasise that these photos are really about something that is located in the wrong places.

Your images are quite varied, from simple detritus to remains of large scale architectural sites. What was it that you felt the images had to have to fit with the books concept?

As I said, all the photos are connected by the idea of isolated, abandoned objects in a natural environment. In the surroundings, where they are located and where photos were taken, there is no active human presence. The diversity you mention is a necessary part of the concept here. What do people put and build in the natural environment and then leave behind. However, this variety later represented a great challenge in the sequencing and pairing of photos during the editing phase.

Do you think that there’s been growth in images and projects which highlight this issue evidence of man’s hand on the environment and do you think they have become more accessible/popular? I’m thinking about Edward Burtynsky and Robin Friend, for example.

Both authors you mention often record already caused and visible pollution on one hand or large industrial and infrastructure facilities on the other hand. However, this is not the case with my photobook. ‘Misplacements’ does not deal directly with the problem of pollution, but it is rather a visual exploration of interactions of abandoned objects which is happening in nature.

The aforementioned authors record highly visible impacts and pollution, while some objects in my photographs are often such that they even escape the gaze of passers-by. Of course, all abandoned objects in nature have a certain negative impact on the environment, but in my case, on a significantly smaller scale. I agree that there is an increasing number of photography projects whose subject is documenting pollution or environmental degradation. I did not have these ambitions and just wanted to create a series of photographs that differs from the usual photographic documentation of pollution but is still somehow connected to the human-nature interaction.

How did the project progress over time, and were there any adjustments made to refine the initial vision and goals?

When, at some point, I realised that I had enough photos that could represent a coherent body of work, I started combining them, pairing them. After the first selection, I was even more careful to catch any abandoned objects in the environment that I could add that would fit the concept of the book. And I actually took some of the most interesting photos during the last months while already preparing my photobook.

Were there many key photographs that you knew would succeed when you took them? Conversely, did some of your pre-planned images fail in execution? (or more generally - was it mostly planned or discovered?)

They were completely discovered. That means I found myself in a certain location, at some place, without any prior research. Therefore, the geography where the photographs were taken is very diverse: from the mountains in India to the outskirts of the city where I live. Absolutely nothing was pre-planned.

What have been the biggest lessons you’ve learned about the process of printing (and preparing to print) a book?

This is not my first photobook, but it is the first self-published one where I had full creative control. I designed and financed it entirely myself in a limited number of 50 copies. Working on a photo book is an extremely creative process, but it should not be rushed. I must have changed at least 10 versions regarding the selection and pairing of the photos, their positioning and the cover.

Some of the photos which were selected at the beginning were later eliminated. When working on a photo book, a photographer enters a completely different dimension of creative work than, for example, during the preparation of the exhibition. In doing so, he delves into the photographs in a different way, analysing their overall visual effect in a specific visual flow. Thus, viewing photos in a photo book or at an exhibition is a different experience for both the viewer and the author.

Although the equipment choice is secondary to your own processes, it inevitably affects the way we work to some extent. What equipment do you currently use and why did you choose it?

I use several cameras, but for many years, my primary camera has been the Canon EOS 5D Mark II with the corresponding Canon lenses. It has proven to be very reliable over the years. I found that due to the way I work, I absolutely need zoom lenses because I cannot carry too much heavy equipment with me on my hikes on heavy accessible and often steep slopes for several hours of walking.

But many times, especially in more urban environments, I came across a subject completely by chance, and in this case, I was saved by a smaller Fujifilm camera, which I often take with me just in case during my wanderings.

Before digital cameras, I worked exclusively with film for more than 20 years. Speaking about cameras, I see myself as a musician who picks up the instrument with which he wants to get the desired sound. Sometimes it's a noisy electric sound, and sometimes it's a tender acoustic sound. In this sense, digital technology is much more suitable for my way of work and for the vision if the final outcome.

Tell me what your favourite two or three photographs from the book are and a little bit about them

I especially like the first and last photos in the book. When designing a photo book, special care must be given to the first and last photos.

For example, the opening photo was taken in Ladakh, India, and I don't really know what kind of object that is. It seems like some kind of fence, but in a location where there are no settlements. And no other objects can be seen in its interior either.

It is a kind of phantom construction that almost resembles a land-art object, but which it is not, of course. It is a typical example of a misplacement. It is similar to the last photo in the book, where the central topic is the sharp road bend, but it ends unexpectedly and illogically in the middle of the landscape.

What is next for you? Where do you see your photography going in terms of subject and style?

I am a landscape photographer, and I am mainly interested in this genre of photography. This year, I am preparing a new solo exhibition where photos of trees will be presented. I like to photograph common subjects such as trees and forests but in a more unconventional way. Some of these tree-related projects are partially featured on my website. But to be honest, I am already playing with the idea of a new photobook or zine project in future.

Lastly, I’d like to offer you a soapbox about something related to the natural world, the benefits of photography, or just living a good life. What would you like to say to readers or encourage them to do?

Photography can mean different things to different people. With the arrival of AI-generated images, very challenging times are coming for photography together with the perception of images in society. It is to be expected that we will be surrounded by more and more AI-generated images. Perhaps, therefore, creative photographic practices might gain even more appreciation, at least in the art world. But it’s hard to say. In general, I was always more interested in the contemplative side of photography. I surely hope that people will not give up the pleasures easily that art photography can give, both for the photographers and for the spectators.

Technical information of the book

You can buy the book at: https://gregorradonjic.wordpress.com/books/

1st edition limited to only 50 signed and numbered copies

Dimension: 260 x 210 mm; 44 pages

HQ digital 4/4 color printing

Inside paper: Fedrigoni Arena Smooth 200 g

Thread sewn; Bodonian binding with exposed spine

Cover: 2 mm board covered with printed Fedrigoni paper