… and what it says about us

Keith Beven

Keith Beven is Emeritus Professor of Hydrology at Lancaster University where he has worked for over 30 years. He has published many academic papers and books on the study and computer modelling of hydrological processes. Since the 1990s he has used mostly 120 film cameras, from 6x6 to 6x17, and more recently Fuji X cameras when travelling light. He has recently produced a second book of images of water called “Panta Rhei – Everything Flows” in support of the charity WaterAid that can be ordered from his website.

'Choice’ is at the heart of the collecting process; a word which expresses its special dual nature as the selection and as the allotment of value, whatever form this value might take.~Susan M. Pearce

Photographs are of course about their makers and are to be read for what they disclose in that regard no less than for what they reveal of the world as their makers comprehend, invent, and describe it.~A.D. Coleman

As photographers we are all collectors of images. We might sort our images in different ways (in digital catalogues and galleries, in Instagram feeds or Pinterest themes, in portfolio boxes … ) or with different subjects (family, holidays, workshops, or on-going project ideas, …)1 but we will all have multiple collections in one form or another. Our collections may not, of course, be limited to photographs; we may have other interests from stamps to train numbers to works of art. In some cases, collecting might become a passion, or even a compulsion2. One of the most well-known collectors of photographs is Elton John, who has employed a full-time curator, Newell Harbin, to build up one of the most extensive private collections of 20th Century photographs, many of which are displayed on the walls of his several houses (though he has some 8000 in total, having started his collection before some major art museums started to take an interest in photography). He is reported as saying that photography is ”the love of my life, in art terms. I love surrounding myself with them”3 and that the reason he works so hard is so that he can collect (though reportedly he has slowed down to only one or so a week now…)4.

The excellent photographic collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles was formed by purchasing the collections of a number of private collectors, including those of Bruno Bischofberger, Arnold Crane, Volker Kahmen/Georg Heusch, and Samuel Wagstaff, Jr. Other extensive collections include those of Artur Walther (a former partner in Goldman Sachs); David Dechman (CEO of a wealth management company); Andrew Pilara (an investment banker); Michael Wilson (producer of many of the James Bond films); Bob and Randi Fisher (son of the founder of Gap); Peter Cohen (another investment banker); and Jamie Lee Curtis (the well-known actress). So, to have a significant collection of celebrated photographs (including celebrated landscape photographers) evidently requires considerable wealth today!

So what about the rest of us with much less disposable income. It does not cost that much to build up collections of our own images of course (even if we could not have done so if digital storage had not become so cheap so quickly6). Perhaps it costs a little bit more for a collection of reproduction prints or books (I suspect that many of us already have too many photo books7). And there may still be current photographers that we admire whose original prints are not tooooo expensive (especially those who sell digital prints and are not so well celebrated). And perhaps it might be worth investing what might seem a considerable sum for something we consider particularly special (even if this might then compete with an investment in new gear). But certainly, for most of us, any thought of systematic or compulsive collecting of originals would be out of our reach.

Unless, perhaps, it is only in the form of digital files. In a recent book, the Swiss author Mona Chollet (currently Editor of Le Monde Diplomatique), discusses her passion for collecting all types of images under different themes on Pinterest8. She will scour magazines, postcards in Museum shops, other digital sources and imaging streams, for images that attract her and which she relates to strongly. These are by no means limited to photographs but include art from around the world and she suggests that

they are the equivalent of the list of things “that make the heart beat faster” drawn up by Sei Shônagon, Lady-in-Waiting to the Empress Consort of Japan in The Pillow Book written in the 11th Century9~Mona Chollet, D’images et d’eau fraiche, p.2310

Such a collection can clearly become compulsive, but has an associated difficulty of dealing with what is essentially choices from an infinite gamut of possibilities, what she calls the “vertigo of the elusive”. She notes that “I felt the almost irresistible force of attraction of this infinite labyrinth, it sucked me in, it siphoned off my attention, my energy, it wore out my eyes.” (p.86), raising the question as to whether this is something to be enjoyed or regretted. Her collection is frequently revised and rearranged because, as she writes,

“..it is also the inside of my brain that I organise, it is the neural connections that I hope to encourage; it seems to me that I am working to increase my mental clarity. To sort, eliminate, reorganise, is to update a body of books or images, and bring it into line with the evolution of my tastes and interests, and thus create a magic mirror which will show me the way, and indicate which subject I should follow now~op.cit., p76/77

The book has, as a subtitle, “what our collections say about us”. We do not perhaps have to be quite so passionate about collecting images as Mona Chollet, as to reveal something about our tastes and interests in what we choose to show others, either on our walls at home, in the galleries on our photography web sites, or sometimes, if we are brave enough, in exhibitions.

Objects are not inert or passive; they help us to give shape to our identities and purpose to our lives. We engage with them in a complex interactive or behavioural dance in the course of which the weight of significance which they carry affects what we think and feel and how we act.~Susan M. Pearce, 2013, p1811

Because showing our collections to others (whether of our own images or of our collections of other photographers or artists) does surely reveal a lot about us. Our own images will reveal our (good or poor) technique, our (good or poor) sense of composition, our tastes in subject matter. Our personal selection of others, especially those we have spent real money on, will reveal the things that make our hearts beat a little faster, though that can, of course, change over time so that some reorganisation and replacement might be necessary. And, we may not need to spend so much.

Nowadays I am recognised as a bona fide collector, but I doubt there are any other collectors who buy so much with so little money. That’s because I leave the collecting of already recognised pieces [and signatures] to others: I concentrate on beautiful things that have yet to be recognised. In short I have always collected things with little market value.~Soetsu Yanagi, 2018, p24612

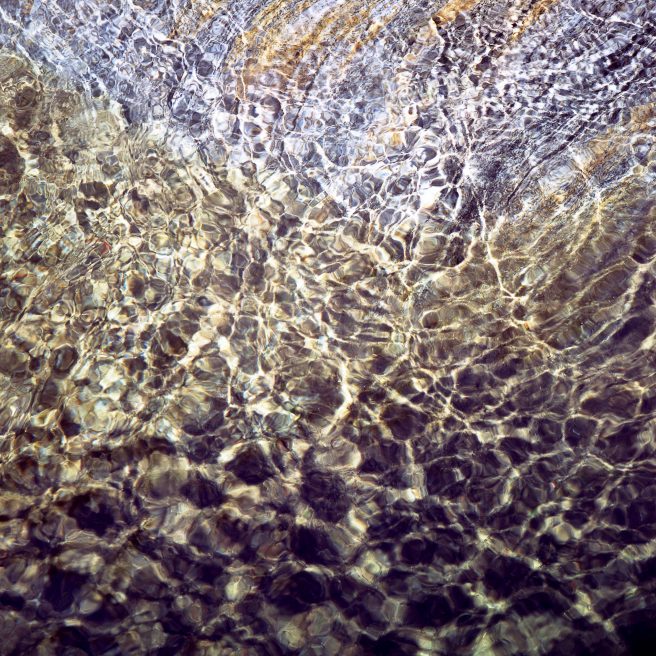

I can remember two important images that sort of started my collection of the images of other photographers many years ago now. Both were not so expensive. The first was one of Ansel Adams, Frozen Lake and Cliffs, Sierra Nevada, 193213, not perhaps one of his best known, but which revealed to me the potential of achieving abstraction in landscape photography. It was not too expensive because I only have a reproduction print, but it was framed and on the wall of my office for decades. The second is the Lynch Clough image of John Blakemore from his All Flows series14, which I also only have in reproduction, and that only in book form (and at first I only had a photocopy that is still in a box somewhere15). That image showed me how water could produce fascinating abstracts, something I have been exploring ever since (and perhaps was trying to do even before… it is a very long time ago now). Later, as money became a little less of a worry, I have original prints from John and Eliza Forder and Paul Kenny to Fay Godwin, Michael Kenna and John Sexton (all when prices were still not toooo expensive!)16. My first purchase from Paul Kenny, Blackstone, Bright Water, 199217, led to a great admiration of his work, and a small collection of his images18.

The point is, I think, that a collection does not need to be large to be personally important. While clearly any collection that is only stored on Instagram or Pinterest does not involve great cost and can be so enormous as to be difficult to control (a little like our own archives of digital images), those that we might put on the wall when space on the wall is limited will have a particular significance. Being built up over time, they are part of our history and development as photographers. They reflect where we were as well as where we are now. They will generally have been chosen with great care and get to be changed from time to time as we ourselves change.

What is true of all objects as such is equally true of those groups of objects that we call collections. They, too, as collective entities as well as in terms of their individual components, have histories which can be traced, and are susceptible to analysis, which, viewed from the appropriate perspective, will reveal the very important part they play in the construction of power and prestige and the manifestation of superiority. They too, are active carriers of meaning, and have a very large share in the creation of individual personality and the way our lives are shaped.~Susan M. Pearce, 2013, p.20

For me that also tended to be the case when taking my own images in the days of film. I had a sort of unspoken question when thinking about taking an image (at least for those when not directly documenting family or travels). Would it be likely to replace one that was already printed or on the wall? If not, then why not wait or look elsewhere because film exposures were limited, and enlargements were expensive (and, of course, even more so now). That inevitably changed with the collection of digital images. Storage is now cheap, multiple variants on an image and bracketing of exposures or focus are cheap. The problem is much more how to organise the collection and decide on which of the variants of the image appeals most. This choice might also change over time so perhaps it is worth keeping all of the variants for now…… It is all too easy to be a little lackadaisical about managing our own collections (and their back-ups – also an important consideration).

Better than one already printed and framed? Val de Nant, Valais, Switzerland (Taken on Ilford 120 Delta 100 in 1997)

But collections require research and careful consideration - in short, a commitment of significant time. To be successful they need regular arranging and managing and rearranging and re-evaluation. There will be moments when choices are made that become more or less fixed – when we finalise a book of our work, or publicise a portfolio, or decide to print and frame an image, or to make a new purchase – but, as in the case of the on-line image collection of Mona Chollet, we are more and more faced with the immensity of the task created by the sheer number of images that build up over time.

Photography is all about such choices. This starts with where we choose to go, the equipment we choose to take, where we choose to stand and what composition and settings we choose for an image, and the moment we choose to take an image. The choices continue with what to keep of all the images taken. There are ways of limiting that task, such as giving star ratings in camera when first reviewing images. Some systems then allow only the chosen starred images to be downloaded for later storage and post-processing. Our starred images can then be kept in categories by themes or places, as digital galleries or printed portfolios.

In some cases we can follow this outcome, if not the process, of selection, such as in the book produced of The Portfolios of Ansel Adams19. In some cases, we can see how a collection can become addictive, such as in the enthusiasm of Martin Parr for his wonderful Autoportraits (started well before the age of selfies, but which he has followed up more recently in Death by Selfie)20, or the attempt by David B. Jenkins to photograph all the See Rock City farm barns scattered through multiple US states21. At this point, the question of when collecting crosses that border to addictive hoarding becomes an issue. Perhaps in the cases of the famous photographic hoarders such as Vivian Maier and Garry Winogrand there was a problem of choice from all the negatives that they had taken (or was just that the act of photographing was more important than the results).

In the late 1990s, the popularity of relational model theories, such as self-psychology, led to the application of these theories to describe collecting as well, which pose the idea that collecting establishes a better sense of self. The psychoanalytic perspective generally identified five main motivations for collecting: for selfish purposes; for selfless purposes; as preservation, restoration, history, and a sense of continuity; as financial investment and as a form of addiction. Addictive collecting was termed hoarding and reflected a "dark side" of collecting behaviour.~Susan M. Pearce, 1994, p.15722

Is there a little of that compulsive hoarding behaviour in us all as photographers23? An imperative feeling of need to add to our collection of visual memories so that they do not get forgotten24. Our collection of images shows that we were there, that we had that experience (which is surely one reason why over-processed and artificially generated images are so dissatisfying). That imperative explains, perhaps, why we are enthusiasts, and why, in some cases, we are prepared to carry equipment to higher elevations and more extreme environments to record the experience. It might also explain why we will try to emulate the work of other photographers we admire and might want to include in our collections, including going to some of the classic landscape locations.

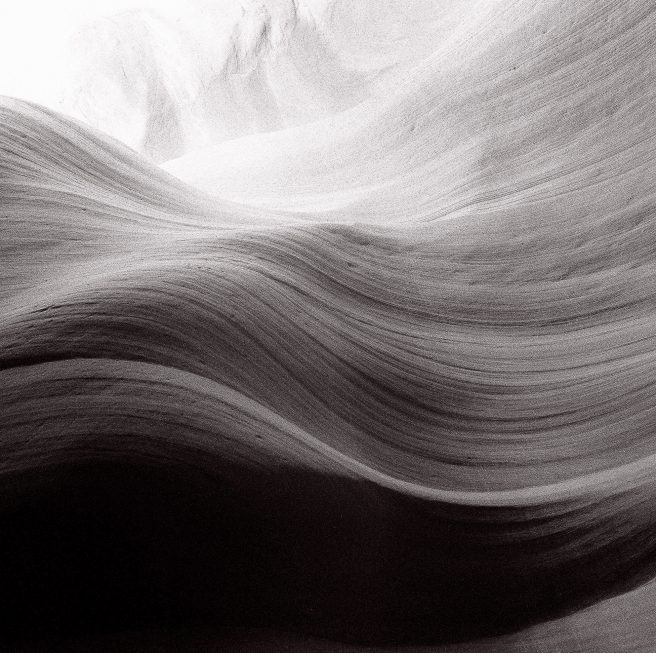

A Classic Location: Lower Antelope Canyon, Page, AZ (taken on Ilford 120 Delta 100 in 1996). Still on the wall.

Fortunately, such dark psychotic behaviour seems to be very well-hidden in most of the landscape photographers I have encountered (including at the On Landscape Meeting of Minds sessions when we still had them). They seem to be mostly a very cheerful and supportive bunch. It would, however, be really interesting to hear a little about your own collections and attitudes to collecting in the comments.

References

- See A Classification of Landscapes in Issue 294

- Following the death of former Italian Prime Minister, Silvio Berlusconi, it was revealed that he had devoted significant resources to collecting some 25 thousand paintings, many of them not very good by all accounts, including purchases made on television auction shows, see https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/27/world/europe/berlusconis-art-collection.html,

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/dec/31/silvio-berlusconi-art-collection-italy-lucas-vianini-curator?ref=upstract.com,

https://www.thecollector.com/silvio-berlusconis-worthless-art-collection/ ) - see https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/elton-john-tate-modern-radical-eye-photography/index.html

- Part of the Elton John and David Furnish collection can be seen in the exhibition Fragile Beauty at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London until 5th January 2025 (though if you are not a member it will cost you £20 to do so). See https://www.vam.ac.uk/exhibitions/fragile-beauty-photographs-from-the-sir-elton-john-and-david-furnish-collection

- Taken from https://loeildelaphotographie.com/en/sir-elton-johns-photography-collection-unveiled/

- I remember a professorial colleague who worked on the processing of radar rainfall images, proudly showing off his new 256Mb hard disk system that had been purchased for his research group in the late 1980s. It had cost £250,000 (or approximately £1000 per Mb). Compare that to a 128Gb SD Card (about £0.0002 per Mb) or a Terabyte Raid Systems today!

- And there are, of course, guides available as to what landscape photography books you should have in your collections, see https://photographycourse.net/best-landscape-photography-books/ or https://amateurphotographer.com/book_reviews/the-best-landscape-photography-books/ . You may not agree with those choices!

- Mona Chollet: D’Images et d’eau fraiche, Flammiron, 2022 (in French)

- From Wikipedia : Sei Shōnagon (c. 966–1017 or 1025) was a Japanese author, poet, and a court lady who served the Empress Teishi (Sadako) around the year 1000 during the middle Heian period. She is the author of The Pillow Book (makura no sōshi). The work is a collection of essays, anecdotes, poems, and descriptive passages which have little connection to one another except for the fact they are ideas and whims of Shōnagon's spurred by moments in her daily life. In it she included lists of all kinds, personal thoughts, interesting events in court, poetry, and some opinions on her contemporaries. While it is mostly a personal work, Shōnagon's writing and poetic skill makes it interesting as a work of literature, and it is valuable as a historical document.

- The translations from D’Images et d’eau fraiche are mine throughout

- Pearce, S., 2013. On collecting: An investigation into collecting in the European tradition. Routledge.

- Soetsu Yanagi, 2018, The beauty of everyday things, Penguin Books

- https://www.anseladams.com/frozen-lake-and-cliffs-sierra-nevada/?doing_wp_cron=1706804874.2047240734100341796875

- https://www.johnblakemore.co.uk/collections/landscape-all-flows/products/lynch-clough-from-sequence-all-flows

- Actually in the pre-internet days I even had a collection of simple photocopies of images that I thought important. The quality was appalling of course, but it was still a reminder of something that had had impact on me. It is so much easier now with digital collections, even if available images are often limited in resolution.

- I once had the chance to buy a copy of The Sea Horizon by Garry Fabien Miller, with tipped in original colour prints, in a bookshop in the Charing Cross Road in London but £75 was much too much money for a book on my budget at the time. How I wish I had a copy now (apparently only 750 were produced and many of those were destroyed in a warehouse fire). To get an idea of some of the images, taken from his house near Bristol looking across the Bristol Channel, see https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2013/sep/12/garry-fabian-miller-sea-horizons-photographs

- https://paul-kenny.co.uk/gallery_283322.html#photos_id=5010416

- See https://www.onlandscape.co.uk/2022/01/full-moon-over-mayo-paul-kenny/

- https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/447910.The_Portfolios_of_Ansel_Adams

- See https://www.lensculture.com/articles/martin-parr-martin-parr-s-hilarious-self-portraits; https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2016/feb/19/the-many-faces-of-martin-parr-autoportrait-returns-in-pictures; https://www.magnumphotos.com/arts-culture/society-arts-culture/martin-parr-interview-book-death-by-selfie/

- See David B Jenkins, Rock City Barns: A Passing Era, 1996 at

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/3201274-rock-city-barns;

https://blueridgecountry.com/newsstand/magazine/rock-city-barns-disappearing-icons-of-the-blue-ridge/ - Susan M. Pearce, The Urge to Collect, in Susan M. Pearce (Ed.) Interpreting Objects and Collections, Routledge, pp157-159, 1994.

This is a subject of serious academic research in psychology– see for example, Nordsletten, A.E. and Mataix-Cols, D., 2012. Hoarding versus collecting: where does pathology diverge from play?. Clinical Psychology review, 32(3), pp.165-176. - See The Road Not Taken article in On Landscape Issue No. 306