“Look at the boaters down there.” Part of a Keystone View Company stereograph titled “Venturing a little too near the Yawning Chasm,” 1903. Library of Congress.

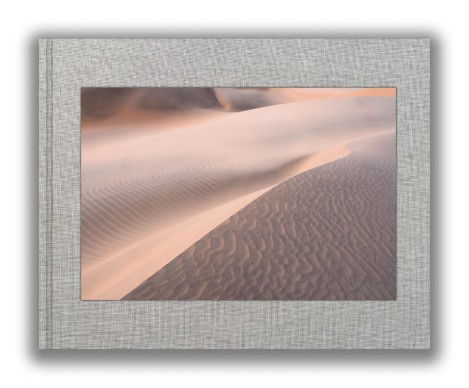

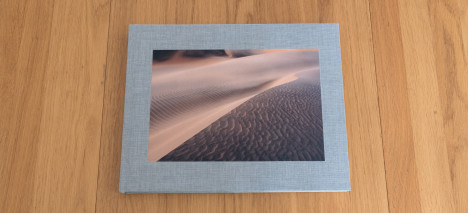

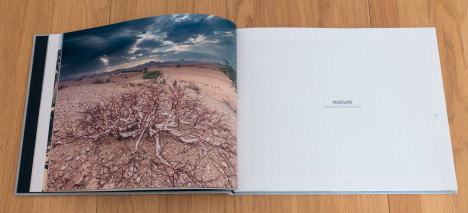

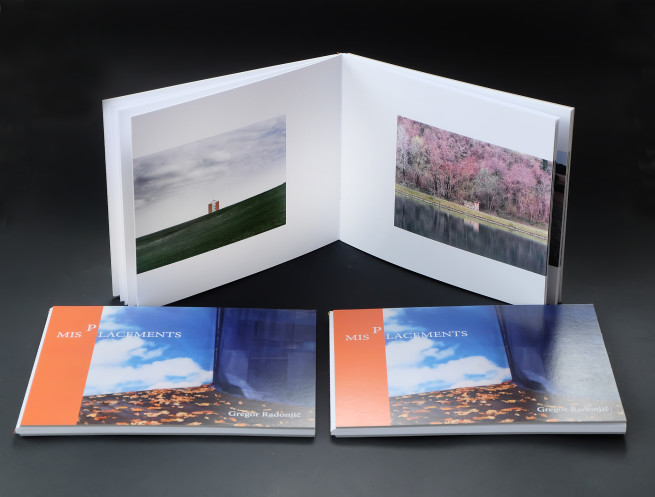

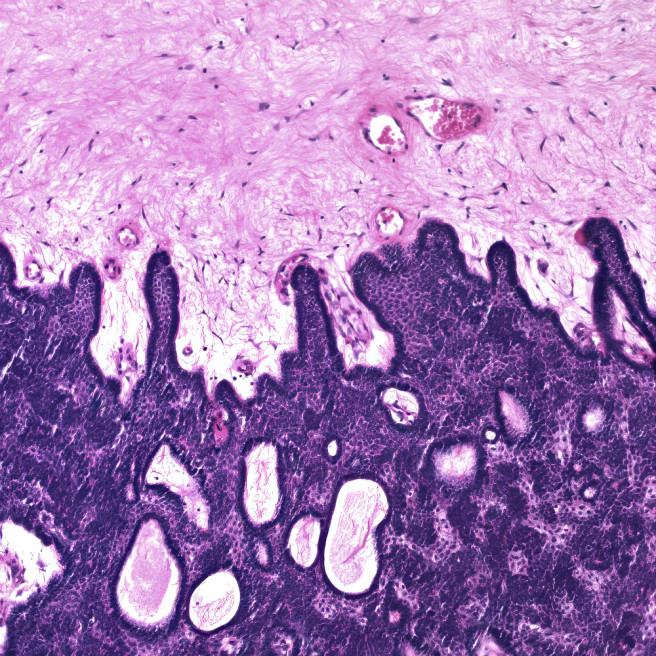

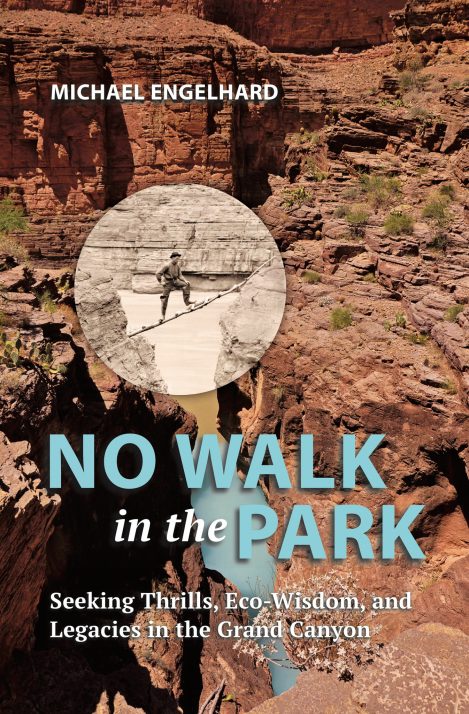

As a nonfiction writer with a passion for history and adventure, I sometimes tap into webs of content that link individuals over centuries, millennia even, and thousands of miles apart, individuals not otherwise not connected. For the cover of my new collection of Grand Canyon essays, No Walk in the Park, I sought an immersive photo from deep within the guts of the great abyss, one that would offer a bottom perspective unlike the abstracted scrimshaw beheld from the rims’ viewpoints.

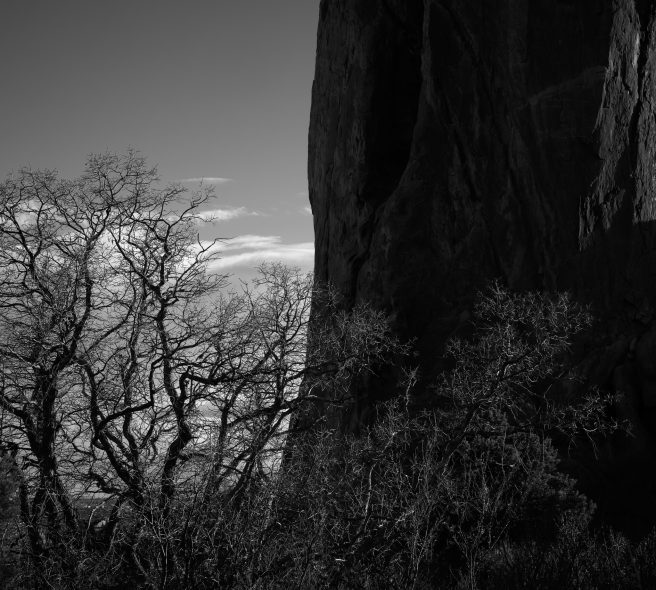

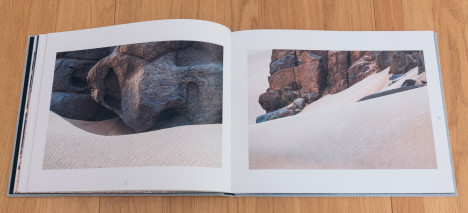

I had long been a fan of early nineteenth-century black-and-white photos taken before and after the “inverse mountain” became a national park in 1919. Many featured tourists that started to flock to this vertical wonderland by rail, or once Route 66 tied it into the road system, by car. There were stills of a Metz 22 (horsepower) Speedster parked precariously near the edge (“Mr. Wing, who handled the wheel, had every confidence in the car and its control, and did not put on the brakes until the front wheels were right at the very edge of the precipice”) and of a hatted, skirted matron who leans and peers over the lip pointing breathlessly at the inner gorge while a second, in a fur coat, grabs the hem of her friend’s cape. Snow mantles the chasm all the way down to the aprons near the Tonto platform, and the gawker does not wear sensible shoes. Tourist behavior has not changed at all in more than one hundred years.

“Now, where is that bridge?” A steam-powered Toledo at the edge, the first car to be driven to the canyon, in 1902. Early cars had to navigate roads built for the stagecoach. Library of Congress.

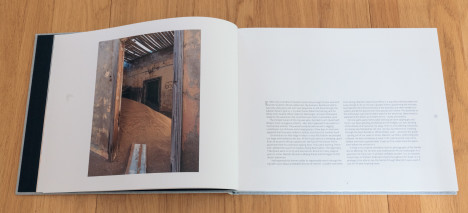

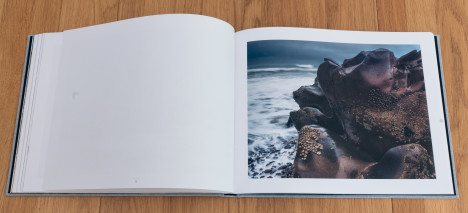

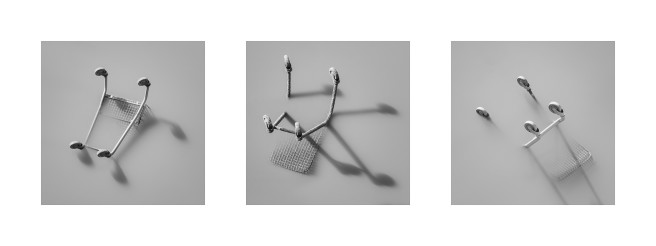

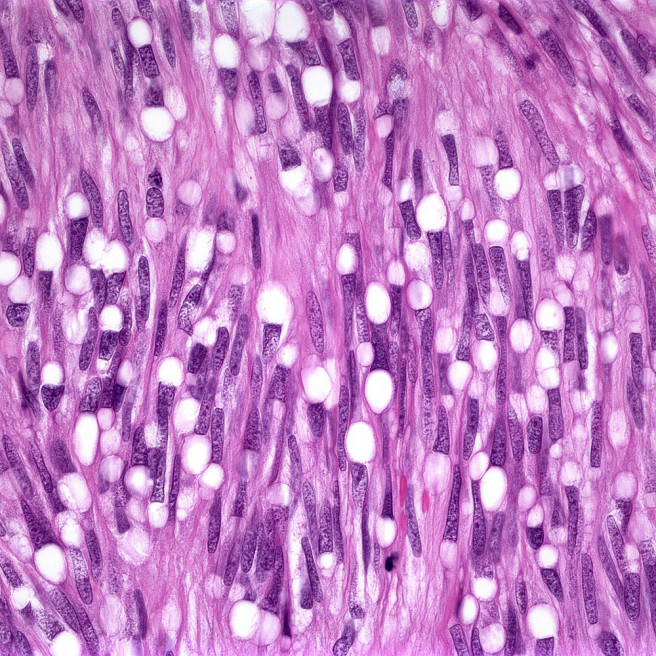

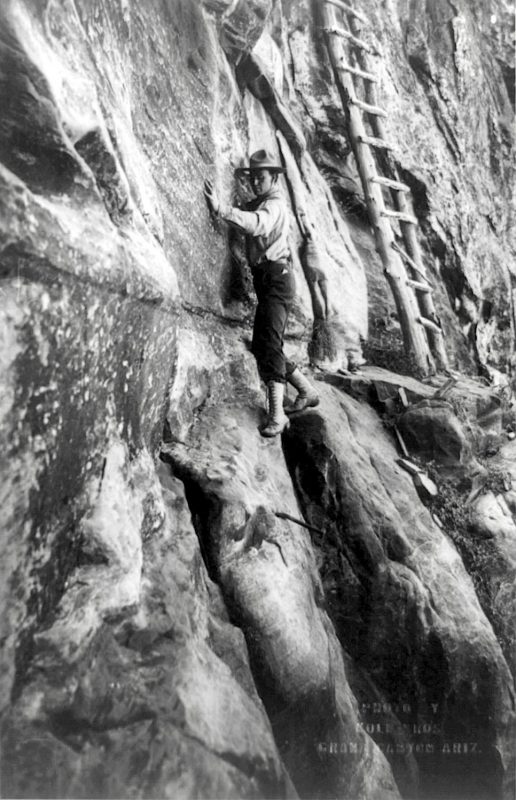

By far the most exciting shots, including many from below the rim, were the work of the two Kolb brothers, proto-influencers who ran a studio on the South Rim, making a living by picturing dudes descending on muleback and selling them the prints upon their return. Hailing from Pittsburgh, Ellsworth and Emery had boated the length of the canyon and more on a hardcore trip from Wyoming to the Gulf of California in 1911, bagging the first-ever footage of the gorge’s rapids. The reels they brought home and for decades showed at the studio still are America’s longest-running film. The Kolbs went the extra mile, literally, for that special frisson or angle.

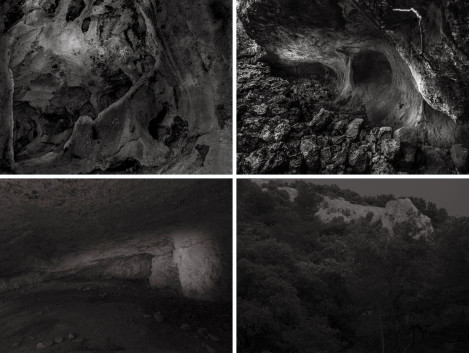

In the autumn of 1930, Ellsworth and his brother Emery tried to enter the cave at the head of Clear Creek, above the inner gorge, not too far from Phantom Ranch, from which spring mysterious, intermittent Cheyava Falls. A tour guide acquaintance of the Kolbs at a distance had mistaken it for “a big sheet of ice.” After verifying by telescope that it was unfrozen water, the Kolbs rigged up a boom-and-pulley system above the North Rim’s Redwall to access it. As the elder brother, Ellsworth decided he’d take the plunge. A heavy storm was brewing, and they were out of food and water, so he took just a canteen. With him only halfway down, a spider on a silk thread a thousand feet above Clear Creek’s bed, one of the most terrific rain and hailstorms either had ever experienced struck. The wind was so strong that Emery feared getting blown off the cliff. Following a search-and-rescue truism that a rescuer in a pickle becomes another casualty, he tied the rope to a gnarled piñion pine, leaving big brother hanging midair. Since the cliff was undercut, Emery later recalled, Ellsworth “was prevented from steadying himself against the wall. This permitted the wind to whirl him round and round until the three wet ropes became one.

“Hold on just another sec for that money shot.” Ellsworth Kolb has lowered his brother Emery from an improvised timber anchor for a unique perspective of the canyon, 1908. Library of Congress.

During a lull Ellsworth managed to “gradually unwind himself,” pushing against the cliff with a pole Emery lowered to him. By dark, the top man had the dangler back up on the belay platform after suffering an “uncomfortable rupture” from the strain of pulling. Ascending in the pitch-black, they spent the night in another cave, hungry, tired, and wet. Knowing what I know of the brothers, they probably posed and grinned while Thor snapped their picture.

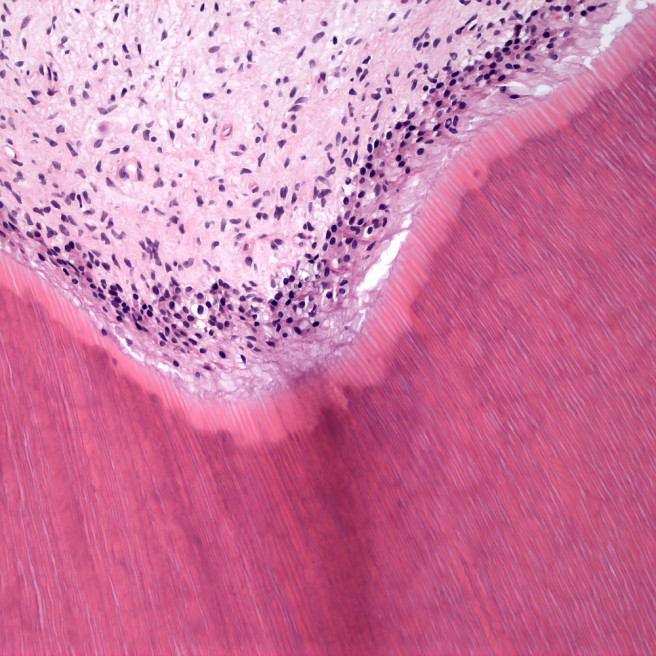

“I’m going out on a ledge here.” One of the Kolb brothers explores the Hummingbird Trail, ca. 1913. You had to be a hummingbird to hang on. Library of Congress.

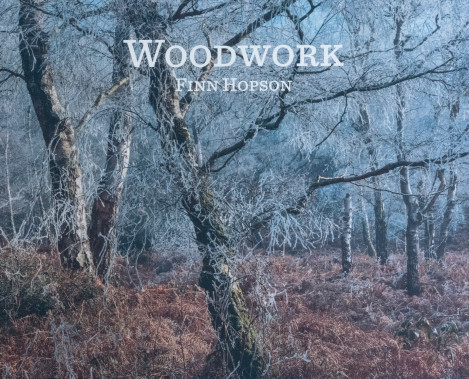

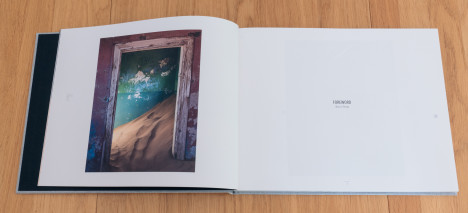

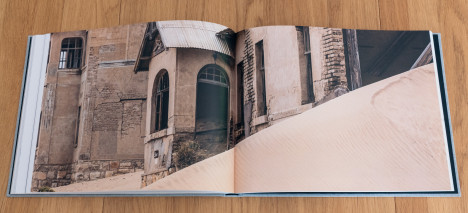

Sifting online archives of the Cline Library’s Special Collections at the University of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff, I quickly settled on a clear winner for the cover. In it, the younger Kolb steps defiantly up a rickety driftwood ladder that bridges narrows stories above the river; he seems to be wearing cavalry boots, a blousy shirt, and a black, small-brimmed hat. Beholding him makes your palms sweat.

I realized right away that the photo had been mislabeled as being from Kanab Creek. I knew the place depicted from river trips on which I had worked. I recognized the cove (here sepia-toned) as the turquoise grotto in which we always moored our rafts for day hikes with clients up to the wonders of Havasu Creek. The stream behind Emery’s figure was the Colorado, running muddy, as it always did before Glen Canyon Dam. I could even determine the vantage from which Ellsworth had framed his brother: the trail skipping from limestone ledge to limestone ledge en route to this barebones landing. I had traipsed along it many times at the end of a sun-blasted day spent by the creek’s glowing pools and horse-mane falls.

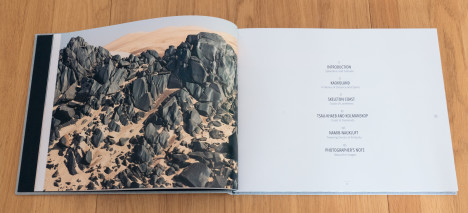

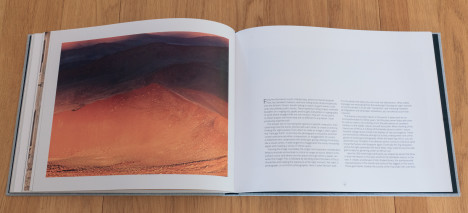

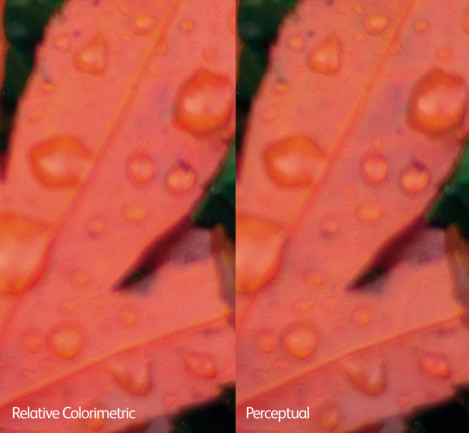

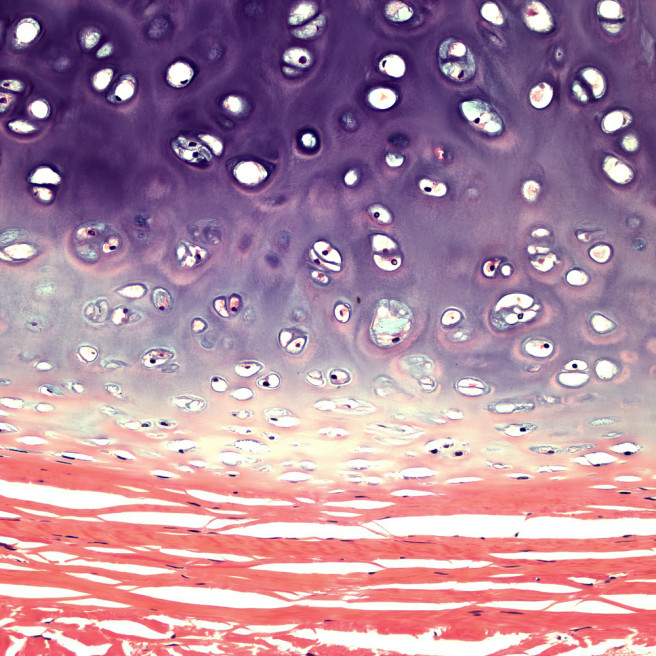

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe are two other photographers whose oeuvre I admire. Their speciality is re-photography, or rather, collages of historical images and their own labor of angles and camera positions researched and meticulously reenacted.

Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Site of a dangerous leap, now overgrown, 2008; inset: colored postcard, not dated. (Note the bushwhacking hands of one of the photographers, in the foreground.) Courtesy of Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe.

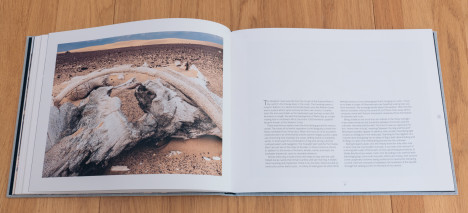

In a different context, re-photography documents environmental changes—or, rarely: sameness—through the hindsight of decades or a century and a half. For the Colorado River watershed, boatmen-photographers John K. Hillers and E. O. Beaman on John Wesley Powell’s second expedition fixed the initial baseline. His lens men may also have launched the fad of slightly surreal or ridiculous canyon photos, though they did not dare picture the floating throne with the Major ensconced in it.

“Armchair traveling, 1872.” Expedition leader John Wesley Powell would read to his men on flatwater stretches from a chair lashed to the deck of his lead boat. U.S. Geological Survey.

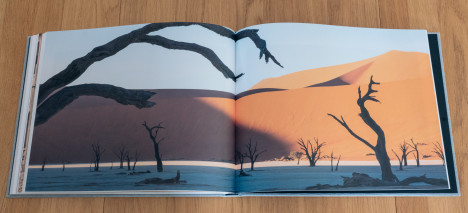

Klett and Wolfe’s Grand Canyon work shines in their spellbinding, at times whimsical Reconstructing the View, a pictorial of double-page panoramas in which the shadows and light of the past merge with those of the present. While these photographers were able to suss out the location of the Kolbs’ most famous dangling shot, Klett simply could not convince Wolfe to assume the dangler’s pose and position. The splendor, wit, and craftsmanship of their tableaus sparked the wish for a similar composition of my own for the cover of No Walk in the Park.

Alas, at the time I lived in Fairbanks, Alaska. A trip south to re-photograph the setting was out of the question, though I felt that I had the exact location nailed down. There was no money for artwork in the publisher’s budget, and the catalogue—showcasing my book’s cover—would go to the printer in less than two weeks.

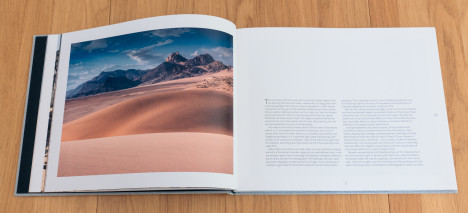

I trawled the Internet listlessly for a suitable image, like a fisherman would an overfished or acidified sea. Within minutes, I did a double take. I clicked on and enlarged a vertical, crisp, well-lit shot of the very same place. Havasu’s waters pulsed neon-blue in the depths, joining a rio muy colorado, both bracketed by the salmon-flesh limestone of the 350-million-year-old Redwall formation. To boot, I could grab a high-resolution, print-quality Flickr file, which came with a Creative Commons license permitting use of the image. As it turned out, a Grand Canyon park ranger on a team-building trip had pushed the shutter button. She described Havasu’s unearthly hue to me as “a color you’d only find inside the glass of a Las Vegas cocktail or as a gummy worm candy.”

When I cropped Emery inside a grayscale circle (suggesting the view field of a spotting scope at an overlook), which I then moved across Erin’s photo on my computer screen, it snapped into a place where it fit almost perfectly. Even Havasu’s cliffs were lining up. It was uncanny, despite the fact that the trail near the mouth of Havasu has few pullouts where an artist might step off-trail and pause, contemplate, and capture this priceless scene.

Strands of visual creativity now bind me to Ellsworth and Emery, to Erin and Byron and Mark, a gossamer circle holding distant strangers.

A nearly perfect match: the book cover of No Walk in the Park, incorporating the mislabeled Kolb photo.

The hunt for the perfect picture has two codas. The university press balked at my idea, or perhaps just at too much author involvement. Their counter comps (designer lingo for “comprehensive layouts”) ran the gamut from horsey typography to a concept that reminded the press director of Emerson’s “transparent eyeball” beholding the desert Southwest but in me evoked Hunter S. Thompson’s, glazed by CBD, bloodshot. After repeated exchanges that did not yield any improved designs, I called it quits, kissing the modest advance goodbye, backing out of my contract over “artistic differences.” I then self-published the book, true terra incognita for me, as the canyon at first had been to the Kolbs, Powell, and his crew. I’ve never felt more in charge of my vision.

And, for the sheer fun of it, my wife, a former graphic designer and collaborator on my books, recently prompted AI software with some keywords and my book’s title. The cover the digital brain quickly spat out, with eye-catching primary colors and reminiscent of 1930s National Parks posters—a style in fashion again that will soon have had its moment, feeling dated—featured an adventurer crossing the chasm on two wire cables or ropes. The result closely resembled the dust jacket of a similar new Grand Canyon book by a major publisher, and we’re still chuckling at that.

- “Look at the boaters down there.” Part of a Keystone View Company stereograph titled “Venturing a little too near the Yawning Chasm,” 1903. Library of Congress.

- “Now, where is that bridge?” A steam-powered Toledo at the edge, the first car to be driven to the canyon, in 1902. Early cars had to navigate roads built for the stagecoach. Library of Congress.

- “Hold on just another sec for that money shot.” Ellsworth Kolb has lowered his brother Emery from an improvised timber anchor for a unique perspective of the canyon, 1908. Library of Congress.

- “Armchair traveling, 1872.” Expedition leader John Wesley Powell would read to his men on flatwater stretches from a chair lashed to the deck of his lead boat. U.S. Geological Survey.

- Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe, Site of a dangerous leap, now overgrown, 2008; inset: colored postcard, not dated. (Note the bushwhacking hands of one of the photographers, in the foreground.) Courtesy of Mark Klett and Byron Wolfe.

- “I’m going out on a ledge here.” On of the Kolb brothers explores an ancient Grand Canyon cliff dwelling, ca. 1913. Library of Congress.

- A nearly perfect match: the book cover of No Walk in the Park, incorporating the mislabeled Kolb photo.